Rationalizing Professional Misconduct: an Examination of Techniques of Neutralization in Lawyer Discipline Proceedings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S.C.C. Court File No. 36583 in the SUPREME COURT of CANADA

S.C.C. Court File No. 36583 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA (ON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL FOR MANITOBA) BETWEEN: SIDNEY GREEN Appellant (Appellant) - and - THE LAW SOCIETY OF MANITOBA Respondent (Respondent) - and – THE FEDERATION OF LAW SOCIETIES OF CANADA Intervener _________________________________________________________________________ FACTUM OF THE INTERVENER, THE FEDERATION OF LAW SOCIETIES OF CANADA (Pursuant to Rules 37 and 59 of the Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada, S.O.R./2002-156) _________________________________________________________________________ McCarthy Tétrault LLP Gowling WLG (Canada) Inc. Suite 5300, Toronto Dominion Bank Tower 160 Elgin Street, Suite 2600 Toronto ON M5K 1E6 Ottawa ON K1P 1C3 Neil Finkelstein ([email protected]) Guy Régimbald Brandon Kain ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Tel: (416) 362-1812 Tel: (613) 786-0197 Fax: (416) 868-0673 Fax: (613) 788-3587 Counsel for the Intervener, Ottawa Agent for the Intervener, The Federation of Law Societies of Canada The Federation of Law Societies of Canada ORIGINAL TO: The Registrar Supreme Court of Canada 301 Wellington Street Ottawa, ON K1A 0J1 COPIES TO: Taylor McCaffrey LLP Burke-Robertson 9th Floor – 400 St. Mary Avenue 441 MacLaren Street, Suite 200 Winnipeg MB R3C 4K5 Ottawa ON K2P 2H3 Charles R. Huband ([email protected]) Robert E. Houston Kevin T. Willaims ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Tel: (204) 988-0428 Tel: (613) 236-9665 Fax: (204) 957-0945 Fax: (613) 235-4430 Counsel for the Appellant Ottawa Agent for the Appellant Law Society of Manitoba Gowling WLG (Canada) Inc. 219 Kennedy Street 160 Elgin Street, Suite 2600 Winnipeg MB R3C 1S8 Ottawa ON K1P 1C3 Rocky Kravetsky ([email protected]) Jeffrey W. -

Department of Justice

Manitoba Justice ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• The Manitoba Law Foundation Board Member Chairperson Garth Smorang ^ Vice-Chair Lori Ferguson Sain ^ Members Monica Adeler ^ Janna Cumming ^ Terumi Kuwada ^ David Kroft (1) Karen Clearwater (1) Diane Stevenson (1) Gary Goodwin (2) Lorna Turnbull (3) (1) Appointed by The Law Society of Manitoba (2) Appointed by the President of the Manitoba Branch, Canadian Bar Association (3) Acting Dean of the Faculty of Law, University of Manitoba (ex officio) ^ Government Appointment Mandate: The Manitoba Law Foundation is established under The Legal Profession Act. Under s. 88 of the Act, the Foundation has a specific statutory mandate which is to encourage and promote: legal education; law research; legal aid services; law reform; and the development and maintenance of law libraries. Authority: The Legal Profession Act Responsibilities: The Foundation distributes grants for programs and projects within its mandate, using interest from lawyers’ pooled trust accounts. The Act requires two statutory grants to be provided by the Foundation – one to Legal Aid Manitoba and the other to the Law Society of Manitoba, the amounts of which are determined by formula contained in the legislation. The Act further gives the Foundation the power to receive applications for and make decisions on other grants, consistent with its purpose, that the Foundation’s Board in its discretion considers advisable. The Manitoba Law Foundation 2 Membership: Ten (10) Board members appointed by the following bodies: a) Five (including the Chairperson and Vice-Chairperson) appointed by the Minister of Justice; b) Three appointed by the Benchers of the Law Society of Manitoba; c) One appointed by the president of the Canadian Bar Association, Manitoba Branch; and d) The Dean of the Faculty of Law at the University of Manitoba, or a member of the Faculty appointed by the Dean. -

Federation of Ontario Law Associations White Paper

FEDERATION OF ONTARIO LAW ASSOCIATIONS & THE TORONTO LAWYERS’ ASSOCIATION COUNTY AND DISTRICT LAW LIBRARIES: ENSURING COMPETENCY IN THE PROFESSION AND ACCESS TO JUSTICE WHITE PAPER 1 Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 1 II. CONTEXT OF LAW LIBRARIES TODAY ............................................................................................................. 5 A. History of Courthouse Libraries, LibraryCo, and LiRN ....................................................................... 5 B. Costs of Maintaining Core Library Collections and Operations ........................................................ 7 C. Services Provided by Law Libraries ................................................................................................... 9 III. THE ROLE OF LAW LIBRARIES IN ONTARIO ................................................................................................ 10 1. Competency .................................................................................................................................... 10 A. Access to Justice .............................................................................................................................. 11 B. Mental Health ................................................................................................................................. 13 IV. Statistics on Library Use ................................................................................................................. -

Diversifying the Bar: Lawyers Make History Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arran

■ Diversifying the bar: lawyers make history Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arranged By Year Called to the Bar, Part 2: 1941 to the Present Click here to download Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arranged By Year Called to the Bar, Part 1: 1797 to 1941 For each lawyer, this document offers some or all of the following information: name gender year and place of birth, and year of death where applicable year called to the bar in Ontario (and/or, until 1889, the year admitted to the courts as a solicitor; from 1889, all lawyers admitted to practice were admitted as both barristers and solicitors, and all were called to the bar) whether appointed K.C. or Q.C. name of diverse community or heritage biographical notes name of nominating person or organization if relevant sources used in preparing the biography (note: living lawyers provided or edited and approved their own biographies including the names of their community or heritage) suggestions for further reading, and photo where available. The biographies are ordered chronologically, by year called to the bar, then alphabetically by last name. To reach a particular period, click on the following links: 1941-1950, 1951-1960, 1961-1970, 1971-1980, 1981-1990, 1991-2000, 2001-. To download the biographies of lawyers called to the bar before 1941, please click Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arranged By Year Called to the Bar, Part 2: 1941 to the Present For more information on the project, including the set of biographies arranged by diverse community rather than by year of call, please click here for the Diversifying the Bar: Lawyers Make History home page. -

South Asia Judicial Barometer

SOUTH ASIA JUDICIAL BAROMETER 1 The Law & Society Trust (LST) is a not-for- The Asian Forum for Human Rights and profit organisation engaged in human rights Development (FORUM-ASIA) works to documentation, legal research and advocacy promote and protect human rights, in Sri Lanka. Our aim is to use rights-based including the right to development, strategies in research, documentation and through collaboration and cooperation advocacy in order to promote and protect among human rights organisations and human rights, enhance public accountability defenders in Asia and beyond. and respect for the rule of law. Address : Address : 3, Kynsey Terrace, Colombo 8, S.P.D Building 3rd Floor, Sri Lanka 79/2 Krungthonburi Road, Tel : +94 11 2684845 Khlong Ton Sai, +94 11 2691228 Khlong San Bangkok, Fax : +94 11 2686843 10600 Thailand Web : lawandsocietytrust.org Tel : +66 (0)2 1082643-45 Email : [email protected] Fax : +66 (0)2 1082646 Facebook : www.fb.me/lstlanka Web : www.forum-asia.org Twitter : @lstlanka E-mail : [email protected] Any responses to this publication are welcome and may be communicated to either organisation via email or post. The opinions expressed in this publication are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publishers. Acknowledgements: Law & Society Trust and FORUM-ASIA would like to thank Amila Jayamaha for editing the chapters, Smriti Daniel for proofreading the publication and Dilhara Pathirana for coordinating the editorial process. The cover was designed by Chanuka Wijayasinghe, who is a designer based in Colombo, Sri Lanka. DISCLAIMER: The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of LST and FORUM-ASIA and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. -

Decision on Disciplinary Action: Malcolm Hassan Zoraik 2018 LSBC 13

2018 LSBC 13 Decision issued: April 20, 2018 Citation issued: October 20, 2016 THE LAW SOCIETY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA In the matter of the Legal Profession Act, SBC 1998, c. 9 and a hearing concerning MALCOLM HASSAN ZORAIK RESPONDENT DECISION OF THE HEARING PANEL ON DISCIPLINARY ACTION Hearing date: January 19, 2018 Written submissions: January 25, 2018, February 1, 2018 and February 8, 2018 Panel: Sandra Weafer, Chair Satwinder Bains, Public representative Sharon D. Matthews, QC Bencher1 Discipline Counsel: Jaia Rai Counsel for the Respondent: Russell Tretiak, QC INTRODUCTION [1] On September 26 2017 this Hearing Panel found that Mr. Zoraik’s conduct in relation to his criminal convictions for fabrication of evidence and public mischief amounted to professional misconduct, and that the matter should not be stayed on 1 Ms. Matthews, QC, did not participate in the preparation of these reasons and was not a member of the panel as of February 27, 2018. As of that date, Ms. Weafer is chair of the panel. DM1891156 2 the basis of delay. This hearing is to determine the appropriate disciplinary action in respect of that misconduct. [2] These disciplinary proceedings are in furtherance of the obligation of the Law Society to govern the legal profession in the public interest by ensuring the independence, integrity, honour and competence of lawyers. As such, the purpose of our job in determining the appropriate disciplinary action is to act in the public interest, maintain high professional standards and protect the public confidence in the legal profession rather than to punish any offender. [3] The position of the Law Society in this matter is that the appropriate disciplinary action is disbarment. -

Aaron Atcheson

RELATED SERVICES Aaron Atcheson Corporate Partner | London Environmental Law 519.931.3526 Financial Services [email protected] Mergers & Acquisitions Municipal, Planning & Land Development Procurement Transactions & Leasing RELATED INDUSTRIES Biography Energy & Natural Resources Projects Aaron Atcheson practices in the area of real estate and business transactions, and energy and infrastructure projects. He is the Lead of the Projects Group, and has been repeatedly recognized as a leading lawyer and expert in energy, environmental law and property development. He concentrates his practice on the development, acquisition, disposition and financing of infrastructure facilities, with a particular focus on the energy sector, across Canada and, with the assistance of local counsel, in the United States and internationally. From 2017- 2020, he served as Chair of Miller Thomson’s National Real Estate Practice Group and sat on the Firm’s Executive Committee. From 2013 to 2020, Lexpert/Report on Business Magazine has listed Aaron among “Canada’s Leading Energy Lawyers”. From 2013 to 2020, Aaron was recognized by the Canadian Legal Lexpert Directory as an expert in Environmental Law and Property Development and as a “Lawyer to Watch” in the Lexpert 2013 Guide to the Leading US/Canada Cross-border Corporate Lawyers in Canada. Aaron was also listed as one of the 2012 Lexpert “Rising Stars: Leading Lawyers Under 40.” For 2020, Aaron is listed as one of the Best Lawyers in Canada for Energy Law and Environmental Law, and is listed in the Acritas Stars global survey of stand-out lawyers. Aaron advises clients on the purchase and sale of real property, leasing and financing transactions, and the development of real property including brownfields. -

Green V. Law Society of Manitoba, 2017 SCC 20 (Canlii)

Green v. Law Society of Manitoba, 2017 SCC 20 (CanLII) Date: 2017-03-30 Docket: 36583 Citation:Green v. Law Society of Manitoba, 2017 SCC 20 (CanLII), <http://canlii.ca/t/h2wx1>, retrieved on 2017-03-30 SUPREME COURT OF CANADA CITATION: Green v. Law Society of Manito APPEAL HEARD: November 9, 20 ba, 2017 SCC 20 16 JUDGMENT RENDERED: March 3 0, 2017 DOCKET: 36583 BETWEEN: Sidney Green Appellant and The Law Society of Manitoba Respondent - and - Federation of Law Societies of Canada Intervener CORAM: McLachlin C.J. and Abella, Moldaver, Karakatsanis, Wagner, Gascon and Côté JJ. REASONS FOR JUDGMENT: Wagner J. (McLachlin C.J. and Moldaver, Karak (paras. 1 to 69) atsanis and Gascon JJ. concurring) DISSENTING REASONS: Abella J. (Côté J. concurring) (paras. 70 to 98) NOTE: This document is subject to editorial revision before its reproduction in final form in the Canada Supreme Court Reports. GREEN v. LAW SOCIETY OF MANITOBA Sidney Green Appellant v. The Law Society of Manitoba Respondent and Federation of Law Societies of Canada Intervener Indexed as: Green v. Law Society of Manitoba 2017 SCC 20 File No.: 36583. 2016: November 9; 2017; March 30. Present: McLachlin C.J. and Abella, Moldaver, Karakatsanis, Wagner, Gascon and Côté JJ. ON APPEAL FROM THE COURT OF APPEAL FOR MANITOBA Law of professions — Barristers and solicitors — Continuing professional development — Law Society suspending lawyer for failing to comply with Rules of The Law Society of Manitoba imposing mandatory professional development — Lawyer seeking declaration that impugned rules invalid because they impose suspension for non-compliance without right to hearing or right of appeal — Whether rules valid in light of Law Society’s mandate under The Legal Profession Act, C.C.S.M., c. -

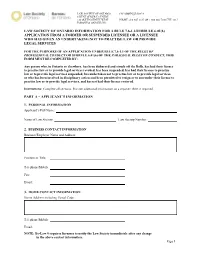

Information for a Rule 7.6-1.1/Subrule 6.01(6)

LAW SOCIETY OF ONTARIO [email protected] CLIENT SERVICE CENTRE 130 QUEEN STREET WEST PHONE: 416-947-3315 OR 1-800-668-7380 EXT. 3315 TORONTO, ON M5H 2N6 LAW SOCIETY OF ONTARIO INFORMATION FOR A RULE 7.6-1.1/SUBRULE 6.01(6) APPLICATION FROM A FORMER OR SUSPENDED LICENSEE OR A LICENSEE WHO HAS GIVEN AN UNDERTAKING NOT TO PRACTISE LAW OR PROVIDE LEGAL SERVICES FOR THE PURPOSES OF AN APPLICATION UNDER RULE 7.6-1.1 OF THE RULES OF PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT OR SUBRULE 6.01(6) OF THE PARALEGAL RULES OF CONDUCT, THIS FORM MUST BE COMPLETED BY: Any person who, in Ontario or elsewhere, has been disbarred and struck off the Rolls, has had their licence to practise law or to provide legal services revoked, has been suspended, has had their licence to practise law or to provide legal services suspended, has undertaken not to practise law or to provide legal services, or who has been involved in disciplinary action and been permitted to resign or to surrender their licence to practise law or to provide legal services, and has not had their licence restored. Instructions: Complete all sections. Provide additional information on a separate sheet if required. PART A – APPLICANT’S INFORMATION 1. PERSONAL INFORMATION Applicant’s Full Name: Name of Law Society: Law Society Number: 2. BUSINESS CONTACT INFORMATION Business/Employer Name and Address: Position or Title: Telephone/Mobile: Fax: Email: 3. HOME CONTACT INFORMATION Home Address including Postal Code: Telephone/Mobile: Email: NOTE: By-Law 8 requires licensees to notify the Law Society immediately after any change in the above contact information. -

Benchers' Digest V.12 No.1 BENCHERS' DIGEST

Benchers' Digest V.12 No.1 BENCHERS' DIGEST Volume 12, Issue #1 January, 1999 Profile of the President Maurice O. Laprairie, Q.C., of Regina, Saskatchewan, was appointed by the Benchers at the December 1998 Convocation to complete the remainder of the 1998 term of Lynn B. MacDonald, Q.C. upon her appointment to the Court of Queen’s Bench. Mr. Laprairie was also elected President of the Law Society for 1999. Maurice O. Laprairie, Q.C. Mr. Laprairie attended the University of Saskatchewan, obtaining an LL.B. President, Law Society of Saskatchewan degree in 1975. He articled to W. M. Elliott, Q.C. of MacPherson, Leslie & Tyerman and was admitted to the Law Society of Saskatchewan in 1977. He has practiced with MacPherson Leslie & Tyerman continuously from 1977 and is currently a senior partner in the firm. Mr. Laprairie’s practice is exclusively in the area of civil litigation. Mr. Laprairie is a director of the Federation of Law Societies of Canada, member of the Regina Bar Association, the Canadian Bar Association and the Saskatchewan Association of Trial Lawyers. He has been chair of the Joint Committee on the Queen’s Bench Rules of Court since its inception. In November, 1994, Mr. Laprairie was elected a Bencher of the Law Society of Saskatchewan. He was re-elected in 1997. He has chaired a number of committees, including the Insurance Committee and Legislation and Policy Committee. He has served on the Complainants Review, Ethics, Executive and Finance Committees. Mr. Laprairie has been involved in many continuing legal education courses and in 1994 he was the recipient of SKLESI’s Outstanding Volunteer Award. -

Reflections on the Law Society of Ontario Statement of Principles

Not Tyranny: Reflections on the Law Society of Ontario Statement of Principles Mary Eberts, OC LSM Bencher, 1995-1999 Heather J. Ross, LLB Bencher, 1995-2019 Nadine Otten Student, Schulich School of Law, Dalhousie University June 25, 2019 The Rule of Law is inextricably linked to and interdependent with the protection of human rights as guaranteed in international law and there can be no full realization of human rights without the operation of the Rule of Law, just as there can be no fully operational Rule of Law that does not accord with international human rights law and standards.1 INTRODUCTION 1 On December 2, 2016, the Challenges Faced by Racialized Licensees working group submitted its final report to LSO Convocation.2 2 After debating this report, Convocation adopted the Equity, Diversity and Inclusion initiative by a vote of 47-0 with 3 abstentions. The Equality, Diversity and Inclusion initiative comprises five strategies * The authors thank The Ross Firm Professional Corporation for its kind assistance in the preparation of this paper. 1 International Commission of Jurists, Tunis Declaration on Reinforcing the Rule of Law and Human Rights (March 2019) at para 4 [the Declaration]. 2 Challenges Faced by Racialized Licensees Working Group, Final Report: Working Together for Change: Strategies to Address Issues of Systemic Racism in the Legal Professions (2016) at 2 [Challenges Report]. 1 NOT TYRANNY to address racism and discrimination in the professions, all recommended in the final report.3 One of those strategies is the Statement -

Jaan Lilles | Lenczner Slaght

1 Jaan Lilles JAAN LILLES is a partner at Lenczner Slaght and the head of the firm’s Professional Liability practice group. Jaan's practice embraces a diverse range of litigation: professional liability, medical malpractice, commercial disputes, franchising matters, defence of class actions, employment and administrative law. He has appeared before all Education levels of court in Ontario, including as lead counsel in the University of Toronto (2009) LLM University of Toronto (2003) LLB Court of Appeal for Ontario, Divisional Court and the Ontario (Honours Standing - 3rd Year) University of Toronto (1999) MA Superior Court of Justice and he has appeared in the Supreme (English Literature) Court of Canada. McGill University (1998) BA (Honours - English Literature) Jaan regularly represents clients before administrative tribunals Bar Admissions both as a prosecutor and as defence counsel. He has handled Ontario (2004) professional discipline matters before the the Law Society Practice Areas Appeals Tribunal and several Discipline Committees of various Commercial Litigation Employment regulated health colleges. He has frequently participated in Professional Liability and Regulation judicial review applications and appeals from administrative Public Law tribunals. Contact T 416-865-3552 A keen interest in the legal theory of privacy led Jaan to pursue [email protected] a Master's of Law degree at the University of Toronto, where his graduate thesis was titled "The Common Law Right to Privacy." Jaan is a regular speaker at continuing legal education events and taught for three years as an adjunct professor at the Faculty of Law, Western University. Jaan has been recognized as a leading lawyer by various organizations including Lexpert, Best Lawyers, and Benchmark Canada.