Decision on Disciplinary Action: Malcolm Hassan Zoraik 2018 LSBC 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Vol. Xxxii, No. 1 1994] Leaving the Practice Of](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1091/vol-xxxii-no-1-1994-leaving-the-practice-of-161091.webp)

[Vol. Xxxii, No. 1 1994] Leaving the Practice Of

116 ALBERTA LAW REVIEW [VOL. XXXII, NO. 1 1994] LEAVING THE PRACTICE OF LAW: THE WHEREFORES AND THE WHYS 1 JOAN BROCKMAN' In 1990, the Be11cl1ersof the Law Society of Alberta En 1990, /es membres du Barreau de /'Alberta ont established a Committee 011 Women and the Legal fonde un comite charge d'etudier /es questions Profession to examine the issues concerning women relatives aux femmes dans /es carrieres juridiques. in the law. This article examines the results of a Le present article examine /es resultats d'1111eenquete comprehensive survey conducted on inactive members exhaustive effectuee pour ce comite, aupres des of the law Society of Alberta for this Committee. The membres inactifs de la Law Society of Alberta. II survey was the second of two surveys conducted by s'agissait de la deuxieme elude du ge11reeffectuee this author. The first survey was conducted on tire par /'auteure. La premiere enquete ciblait /es active members of the Law Society of Alberta. membres actifs du Barreau. The survey produced a number of interesting results L 'enquete a permis d'obtenir uncertain nombre de for those individuals consideri11gthe practise of law resultats interessants pour /es personnes qui as a professio11 and for those already withi,r the envisagent de faire carriere en droit et pour celles profession. The survey looked at the characteristics qui pratiquent deja. Elle a examine /es of the respondents, their reasons for leaving the caracteristiques des personnes imerrogees, /es practise of law, and their perceptions and experience raisons qui /es 0111motive a renoncer a la pratique with bias within the profession. -

Canadian Lawyer Mobility and Law Society Conflict of Interest*

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 18, Issue 1 1994 Article 4 Canadian Lawyer Mobility and Law Society Conflict of Interest Alexander J. Black∗ ∗ Copyright c 1994 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Canadian Lawyer Mobility and Law Society Conflict of Interest Alexander J. Black Abstract This Article discusses inter-jurisdictional mobility of lawyers in Canada, comparing Canadian practice to European Community (”Community” or “EC”) reforms and U.S. practice. Ironically, the Community eschews using the label ”federal” because the process of European unification is ongoing, yet the new regime for the transfer of lawyers between EC Member States is freer and less fettered than the transfer regimes in Canada. In the United States, the mobility of lawyers is dependent upon reciprocal agreements between state bar associations whereby qualification in one state bar permits direct entry to practice in other states. Hence, this Article compares the rules affecting lawyer mobility in the ten Canadian provinces and two territories, the European Community, and the United States, specifically New York State, a jurisdiction receptive to foreign law degrees. CANADIAN LAWYER MOBILITY AND LAW SOCIETY CONFLICT OF INTEREST* AlexanderJ. Black** Un Canadien errant, bani de son foyer Parcourant en pleurant, des pays 6trangers Un jour triste et pensif, assis au bord des flots En courant fugitif, il s'adressa ses mots Si tu vois mon pays, mon pays malheureux Va dire a mes amis, que je me souviens d'eux.' CONTENTS Introduction ......................... ..................... 119 I. Canadian Lawyer Mobility ........................... 121 A. -

Articling & Summer Student

BROWNLEE LLP EDMONTON CALGARY ARTICLING & SUMMER STUDENT Ryan R. Ewasiuk Derek J. King #2200 Commerce Place 700, 396 – 11th Avenue S.W. HANDBOOK 10155 – 102 Street N.W. Calgary, Alberta T2R 0C5 Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4G8 BROWNLEE LLP SUMMER AND ARTICLING STUDENT HANDBOOK WE LOOK FORWARD TO MEETING YOU As you can see, at Brownlee it is our goal to be informative and transparent throughout the summer and articling application processes. We want you to be as informed as possible so that you can choose the firm TABLE OF CONTENTS that is right for you. Frankly, that’s what is best for us too. If you have any further questions or concerns, please do not hesitate to contact any member of the Edmonton Articling Committee: Welcome to Brownlee LLP 1 Ryan Ewasiuk, Chair What makes Brownlee different from other firms? 2 [email protected] (780) 497-4850 Brownlee’s practice areas and client base 3 Our clients 4 John McDonnell [email protected] Our practice areas 5 (780) 497-4801 What kind of social culture exists at Brownlee? 7 Who are we looking for? 8 Jill Sheward [email protected] What should you expect when you article at Brownlee? 9 (780) 497-4835 What should you expect when you summer at Brownlee? 11 Kristjana Kellgren How will CPLED fit into your day? 12 [email protected] Who sits on our Edmonton Articling Committee? 13 (780) 497-4890 Resumés and applications for summer and articling student positions 16 What should you expect during Articling Interview Week? 17 All inquiries regarding summer or articling positions with our Calgary office may contact: Before Interview Week 17 During Interview Week 18 Derek King [email protected] Call Day 19 (403) 260-1472 Edmonton summer student on-campus interviews 20 We look forward to meeting you 21 offer.) However, if your 2nd choice calls first, don’t Edmonton Summer Student On-Campus Interviews ? be afraid to ask for a few minutes to consider the offer (you have until 12:00 p.m. -

Federation of Ontario Law Associations White Paper

FEDERATION OF ONTARIO LAW ASSOCIATIONS & THE TORONTO LAWYERS’ ASSOCIATION COUNTY AND DISTRICT LAW LIBRARIES: ENSURING COMPETENCY IN THE PROFESSION AND ACCESS TO JUSTICE WHITE PAPER 1 Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 1 II. CONTEXT OF LAW LIBRARIES TODAY ............................................................................................................. 5 A. History of Courthouse Libraries, LibraryCo, and LiRN ....................................................................... 5 B. Costs of Maintaining Core Library Collections and Operations ........................................................ 7 C. Services Provided by Law Libraries ................................................................................................... 9 III. THE ROLE OF LAW LIBRARIES IN ONTARIO ................................................................................................ 10 1. Competency .................................................................................................................................... 10 A. Access to Justice .............................................................................................................................. 11 B. Mental Health ................................................................................................................................. 13 IV. Statistics on Library Use ................................................................................................................. -

The Rules of the Law Society of Alberta

Law Society of Alberta The Rules of the Law Society of Alberta December 1, 2016 Format updated April 2016 Law Society of Alberta The Rules of the Law Society of Alberta ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Amendment Table – 2016_V5 Amendment Amendment Other Rules Modified Description of Change Amendment Source Authorized Effective Impact 88.1 (10) To broaden the pool of decision makers December 1, December 1, Bencher Meeting when necessary 2016 2016 119.46 To allow law firms to use bank drafts and December 1, December 1, Bencher Meeting money orders with minimal effort 2016 2016 Changes listed in this table are ones made to Version "2016_V4" of the Rules. Where an amendment to the substance of a rule or subrule has been made since June 3, 2001, the amendment month and year are marked at the end of the Rule. Amendments made prior to June 3, 2001 are not marked in this document. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Version #: 2016_V5 www.lawsociety.ab.ca December 1, 2016 Law Society of Alberta The Rules of the Law Society of Alberta ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents PART 1 ORGANIZATION AND ADMINISTRATION OF THE SOCIETY 1 Interpretation .........................................................................................................................................1-1 -

Diversifying the Bar: Lawyers Make History Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arran

■ Diversifying the bar: lawyers make history Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arranged By Year Called to the Bar, Part 2: 1941 to the Present Click here to download Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arranged By Year Called to the Bar, Part 1: 1797 to 1941 For each lawyer, this document offers some or all of the following information: name gender year and place of birth, and year of death where applicable year called to the bar in Ontario (and/or, until 1889, the year admitted to the courts as a solicitor; from 1889, all lawyers admitted to practice were admitted as both barristers and solicitors, and all were called to the bar) whether appointed K.C. or Q.C. name of diverse community or heritage biographical notes name of nominating person or organization if relevant sources used in preparing the biography (note: living lawyers provided or edited and approved their own biographies including the names of their community or heritage) suggestions for further reading, and photo where available. The biographies are ordered chronologically, by year called to the bar, then alphabetically by last name. To reach a particular period, click on the following links: 1941-1950, 1951-1960, 1961-1970, 1971-1980, 1981-1990, 1991-2000, 2001-. To download the biographies of lawyers called to the bar before 1941, please click Biographies of Early and Exceptional Ontario Lawyers of Diverse Communities Arranged By Year Called to the Bar, Part 2: 1941 to the Present For more information on the project, including the set of biographies arranged by diverse community rather than by year of call, please click here for the Diversifying the Bar: Lawyers Make History home page. -

Aaron Atcheson

RELATED SERVICES Aaron Atcheson Corporate Partner | London Environmental Law 519.931.3526 Financial Services [email protected] Mergers & Acquisitions Municipal, Planning & Land Development Procurement Transactions & Leasing RELATED INDUSTRIES Biography Energy & Natural Resources Projects Aaron Atcheson practices in the area of real estate and business transactions, and energy and infrastructure projects. He is the Lead of the Projects Group, and has been repeatedly recognized as a leading lawyer and expert in energy, environmental law and property development. He concentrates his practice on the development, acquisition, disposition and financing of infrastructure facilities, with a particular focus on the energy sector, across Canada and, with the assistance of local counsel, in the United States and internationally. From 2017- 2020, he served as Chair of Miller Thomson’s National Real Estate Practice Group and sat on the Firm’s Executive Committee. From 2013 to 2020, Lexpert/Report on Business Magazine has listed Aaron among “Canada’s Leading Energy Lawyers”. From 2013 to 2020, Aaron was recognized by the Canadian Legal Lexpert Directory as an expert in Environmental Law and Property Development and as a “Lawyer to Watch” in the Lexpert 2013 Guide to the Leading US/Canada Cross-border Corporate Lawyers in Canada. Aaron was also listed as one of the 2012 Lexpert “Rising Stars: Leading Lawyers Under 40.” For 2020, Aaron is listed as one of the Best Lawyers in Canada for Energy Law and Environmental Law, and is listed in the Acritas Stars global survey of stand-out lawyers. Aaron advises clients on the purchase and sale of real property, leasing and financing transactions, and the development of real property including brownfields. -

Information for a Rule 7.6-1.1/Subrule 6.01(6)

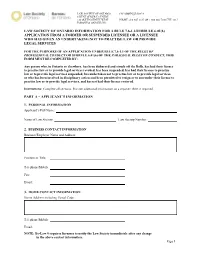

LAW SOCIETY OF ONTARIO [email protected] CLIENT SERVICE CENTRE 130 QUEEN STREET WEST PHONE: 416-947-3315 OR 1-800-668-7380 EXT. 3315 TORONTO, ON M5H 2N6 LAW SOCIETY OF ONTARIO INFORMATION FOR A RULE 7.6-1.1/SUBRULE 6.01(6) APPLICATION FROM A FORMER OR SUSPENDED LICENSEE OR A LICENSEE WHO HAS GIVEN AN UNDERTAKING NOT TO PRACTISE LAW OR PROVIDE LEGAL SERVICES FOR THE PURPOSES OF AN APPLICATION UNDER RULE 7.6-1.1 OF THE RULES OF PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT OR SUBRULE 6.01(6) OF THE PARALEGAL RULES OF CONDUCT, THIS FORM MUST BE COMPLETED BY: Any person who, in Ontario or elsewhere, has been disbarred and struck off the Rolls, has had their licence to practise law or to provide legal services revoked, has been suspended, has had their licence to practise law or to provide legal services suspended, has undertaken not to practise law or to provide legal services, or who has been involved in disciplinary action and been permitted to resign or to surrender their licence to practise law or to provide legal services, and has not had their licence restored. Instructions: Complete all sections. Provide additional information on a separate sheet if required. PART A – APPLICANT’S INFORMATION 1. PERSONAL INFORMATION Applicant’s Full Name: Name of Law Society: Law Society Number: 2. BUSINESS CONTACT INFORMATION Business/Employer Name and Address: Position or Title: Telephone/Mobile: Fax: Email: 3. HOME CONTACT INFORMATION Home Address including Postal Code: Telephone/Mobile: Email: NOTE: By-Law 8 requires licensees to notify the Law Society immediately after any change in the above contact information. -

Reflections on the Law Society of Ontario Statement of Principles

Not Tyranny: Reflections on the Law Society of Ontario Statement of Principles Mary Eberts, OC LSM Bencher, 1995-1999 Heather J. Ross, LLB Bencher, 1995-2019 Nadine Otten Student, Schulich School of Law, Dalhousie University June 25, 2019 The Rule of Law is inextricably linked to and interdependent with the protection of human rights as guaranteed in international law and there can be no full realization of human rights without the operation of the Rule of Law, just as there can be no fully operational Rule of Law that does not accord with international human rights law and standards.1 INTRODUCTION 1 On December 2, 2016, the Challenges Faced by Racialized Licensees working group submitted its final report to LSO Convocation.2 2 After debating this report, Convocation adopted the Equity, Diversity and Inclusion initiative by a vote of 47-0 with 3 abstentions. The Equality, Diversity and Inclusion initiative comprises five strategies * The authors thank The Ross Firm Professional Corporation for its kind assistance in the preparation of this paper. 1 International Commission of Jurists, Tunis Declaration on Reinforcing the Rule of Law and Human Rights (March 2019) at para 4 [the Declaration]. 2 Challenges Faced by Racialized Licensees Working Group, Final Report: Working Together for Change: Strategies to Address Issues of Systemic Racism in the Legal Professions (2016) at 2 [Challenges Report]. 1 NOT TYRANNY to address racism and discrimination in the professions, all recommended in the final report.3 One of those strategies is the Statement -

Jaan Lilles | Lenczner Slaght

1 Jaan Lilles JAAN LILLES is a partner at Lenczner Slaght and the head of the firm’s Professional Liability practice group. Jaan's practice embraces a diverse range of litigation: professional liability, medical malpractice, commercial disputes, franchising matters, defence of class actions, employment and administrative law. He has appeared before all Education levels of court in Ontario, including as lead counsel in the University of Toronto (2009) LLM University of Toronto (2003) LLB Court of Appeal for Ontario, Divisional Court and the Ontario (Honours Standing - 3rd Year) University of Toronto (1999) MA Superior Court of Justice and he has appeared in the Supreme (English Literature) Court of Canada. McGill University (1998) BA (Honours - English Literature) Jaan regularly represents clients before administrative tribunals Bar Admissions both as a prosecutor and as defence counsel. He has handled Ontario (2004) professional discipline matters before the the Law Society Practice Areas Appeals Tribunal and several Discipline Committees of various Commercial Litigation Employment regulated health colleges. He has frequently participated in Professional Liability and Regulation judicial review applications and appeals from administrative Public Law tribunals. Contact T 416-865-3552 A keen interest in the legal theory of privacy led Jaan to pursue [email protected] a Master's of Law degree at the University of Toronto, where his graduate thesis was titled "The Common Law Right to Privacy." Jaan is a regular speaker at continuing legal education events and taught for three years as an adjunct professor at the Faculty of Law, Western University. Jaan has been recognized as a leading lawyer by various organizations including Lexpert, Best Lawyers, and Benchmark Canada. -

The Law Society of Ontario's Assessment of Capacity In

The Law Society of Ontario’s Assessment of Capacity in Relation to Mental Illness: A Critical Analysis by David Andrew LeMesurier A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws Faculty of Law University of Toronto © Copyright by David Andrew LeMesurier 2020 The Law Society of Ontario’s Assessment of Capacity in Relation to Mental Illness: A Critical Analysis David Andrew LeMesurier Master of Laws Faculty of Law University of Toronto 2020 Abstract Over the past 20 years, a number of studies across the globe have found that mental health issues—including substance abuse, depression, anxiety, and other forms of psychopathology— are especially acute in the legal profession. The Law Society of Ontario (“Law Society”), the regulator of the legal professions in the province, has a role to play in addressing these issues, particularly due to its statutory jurisdiction over the capacity of lawyers and paralegals (“licensees”). In this paper, I review in depth the Law Society’s current approach to licensee capacity concerns in its applications before the Law Society Tribunal. My critical examination of the current coercive processes is informed by their impacts on the autonomy interests of licensees. Ultimately, I argue that in light of these impacts, the Law Society’s authority with respect to licensee capacity must be strictly and narrowly interpreted, to the greatest benefit of the individuals at issue. ii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my SJD Advisor, Michaël Lessard, and my Supervisor, Professor Trudo Lemmens, both of whom provided a great deal of appreciated feedback on my initial drafts. -

Worker Referral Information

WORKER REFERRAL INFORMATION If you want a representative or help to prepare for your Workplace Safety and Insurance Appeals Tribunal (WSIAT) appeal, you can contact: YOUR UNION: if you are a union member. OFFICE OF THE WORKER ADVISER (OWA): The OWA provides free and confidential education, advice, and representation services to non-union workers who have been injured at work (and their survivors). For more information about the OWA, please contact them directly: 1-800-435-8980 (toll-free in Ontario) 1-416-325-8570 (Toronto) 1-800-660-6769 (toll-free in Canada) 1-800-661-6365 (français, sans frais) 1-866-445-3092 (TTY) www.owa.gov.on.ca LEGAL AID AND COMMUNITY LEGAL CLINICS: Legal Aid Ontario, an independent agency funded largely by the Province of Ontario, is responsible for the delivery of legal aid services to low-income individuals throughout Ontario. Legal Aid Ontario funds Community Legal Clinics across the province. To receive services from a legal clinic, you must live in the area it services and qualify financially. Some of these clinics provide assistance in workplace insurance matters. Their services include providing summary advice, providing assistance with appeals, and providing full representation at WSIAT hearings. For information about Legal Aid and Community Legal Clinics, please contact Legal Aid directly: 1-800-668-8258 (toll-free in Ontario) 416-979-1446 (Toronto) 416-598-8867 and 1-866-641-8867 (TTY) www.legalaid.on.ca LAWYERS AND PARALEGALS: For a fee, a lawyer or licensed paralegal can assist you in preparing for or presenting your WSIAT appeal.