The Roman Conquest of Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Caledonia 1698-1700: Scotland's Twice-Lost Colony

71 “New Caledonia 1698-1700: Scotland’s Twice-Lost Colony” Ignacio Gallup-Díaz, Bryn Mawr College “Lost Colonies” Conference, March 26-27, 2004 (Please do not cite, quote, or circulate without written permission from the author) This paper explores the manner in which the troubled relationship between Scotland and England played itself out in the arena of imperial expansion in the Americas. How did Scotland, a nation-state attempting to free itself from its problematic relationship with a mightier southern neighbor, act upon the colonial stage it had chosen in the Darién region of eastern Panamá? How did a nation-state that occupied the subject position in a colonial relationship itself perform as a colonizer? Informed by David Armitage’s persuasive description of the elements that differentiated the Scottish vision of empire from English expansionist thinking,1 the paper sets out to discover whether Scottish sailors, soldiers and settlers-- the individuals acting on the front lines of the nation’s expansionist effort-- interacted with the Darién’s Tule2 people in a manner that also distinguished them from their English competitors. 1. D. Armitage, “The Scottish Vision of Empire: Intellectual Origins of the Darién Venture,” in John Robertson, ed., A Union for Empire: Political Thought and the Union of 1707, (Cambridge University Press, 1995), pp. 97-121; see also his Ideological Origins of the British Empire, (Cambridge UP, 2000), pp. 158-162. 2. The San Blas Kuna Indians, the descendants of the early modern indigenous peoples of Panamá, use the word “Tule” to describe themselves, and this is the term that I shall use for the actors in this paper. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47–410

no nonsense Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47–410 – interpretation ltd interpretation Contract number 1446 May 2011 no nonsense–interpretation ltd 27 Lyth Hill Road Bayston Hill Shrewsbury SY3 0EW www.nononsense-interpretation.co.uk Cadw would like to thank Richard Brewer, Research Keeper of Roman Archaeology, Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales, for his insight, help and support throughout the writing of this plan. Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47-410 Cadw 2011 no nonsense-interpretation ltd 2 Contents 1. Roman conquest, occupation and settlement of Wales AD 47410 .............................................. 5 1.1 Relationship to other plans under the HTP............................................................................. 5 1.2 Linking our Roman assets ....................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Sites not in Wales .................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Criteria for the selection of sites in this plan .......................................................................... 9 2. Why read this plan? ...................................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Aim what we want to achieve ........................................................................................... 10 2.2 Objectives............................................................................................................................. -

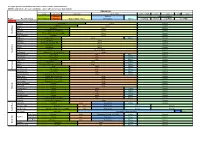

A Very Rough Guide to the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of The

A Very Rough Guide To the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of the British Isles (NB This only includes the major contributors - others will have had more limited input) TIMELINE (AD) ? - 43 43 - c410 c410 - 878 c878 - 1066 1066 -> c1086 1169 1283 -> c1289 1290 (limited) (limited) Normans (limited) Region Pre 1974 County Ancient Britons Romans Angles / Saxon / Jutes Norwegians Danes conq Engl inv Irel conq Wales Isle of Man ENGLAND Cornwall Dumnonii Saxon Norman Devon Dumnonii Saxon Norman Dorset Durotriges Saxon Norman Somerset Durotriges (S), Belgae (N) Saxon Norman South West South Wiltshire Belgae (S&W), Atrebates (N&E) Saxon Norman Gloucestershire Dobunni Saxon Norman Middlesex Catuvellauni Saxon Danes Norman Berkshire Atrebates Saxon Norman Hampshire Belgae (S), Atrebates (N) Saxon Norman Surrey Regnenses Saxon Norman Sussex Regnenses Saxon Norman Kent Canti Jute then Saxon Norman South East South Oxfordshire Dobunni (W), Catuvellauni (E) Angle Norman Buckinghamshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Bedfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Hertfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Essex Trinovantes Saxon Danes Norman Suffolk Trinovantes (S & mid), Iceni (N) Angle Danes Norman Norfolk Iceni Angle Danes Norman East Anglia East Cambridgeshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Huntingdonshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Northamptonshire Catuvellauni (S), Coritani (N) Angle Danes Norman Warwickshire Coritani (E), Cornovii (W) Angle Norman Worcestershire Dobunni (S), Cornovii (N) Angle Norman Herefordshire Dobunni (S), Cornovii -

The Cultural and Ideological Significance of Representations of Boudica During the Reigns of Elizabeth I and James I

EXETER UNIVERSITY AND UNIVERSITÉ D’ORLÉANS The Cultural and Ideological Significance Of Representations of Boudica During the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I. Submitted by Samantha FRENEE-HUTCHINS to the universities of Exeter and Orléans as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, June 2009. This thesis is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ..................................... (signature) 2 Abstract in English: This study follows the trail of Boudica from her rediscovery in Classical texts by the humanist scholars of the fifteenth century to her didactic and nationalist representations by Italian, English, Welsh and Scottish historians such as Polydore Virgil, Hector Boece, Humphrey Llwyd, Raphael Holinshed, John Stow, William Camden, John Speed and Edmund Bolton. In the literary domain her story was appropriated under Elizabeth I and James I by poets and playwrights who included James Aske, Edmund Spenser, Ben Jonson, William Shakespeare, A. Gent and John Fletcher. As a political, religious and military figure in the middle of the first century AD this Celtic and regional queen of Norfolk is placed at the beginning of British history. In a gesture of revenge and despair she had united a great number of British tribes and opposed the Roman Empire in a tragic effort to obtain liberty for her family and her people. -

Fishbourne: a Roman Palace and Its Garden, 1971, Barry W. Cunliffe, 0801812666, 9780801812668, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1971

Fishbourne: A Roman Palace and Its Garden, 1971, Barry W. Cunliffe, 0801812666, 9780801812668, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1971 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1O80BJ2 http://goo.gl/Rblvo http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fishbourne_A_Roman_Palace_and_Its_Garden DOWNLOAD http://goo.gl/R4Dxp http://bit.ly/W9p35D The Roman Villa in Britain , Albert Lionel Frederick Rivet, 1969, Pavements, Mosaic, 299 pages. Excavations at Fishbourne, 1961-1969, Issue 26, Volume 1 , Barry W. Cunliffe, 1971, History, 221 pages. Facing the Ocean The Atlantic and Its Peoples, 8000 BC-AD 1500, Barry W. Cunliffe, Jan 1, 2001, History, 600 pages. An illustrated history of the peoples of "the Atlantic rim" explores the inter- relatedness of European cultures that stretched from Iceland to Gibralter.. The Romans at Ribchester discovery and excavation, B. J. N. Edwards, University of Lancaster. Centre for North-West Regional Studies, Jan 1, 2000, History, 101 pages. Germania , Cornelius Tacitus, 1970, History, 175 pages. Offers a portrait of Julius Agricola - the governor of Roman Britain and Tacitus' father-in-law - and an account of Britain that has come down to us. This book provides. The Recent Discoveries of Roman Remains Found in Repairing the North Wall of the City of Chester (A Series of Papers Read Before the Chester Archaeological and Historic Society, Etc., and Reprinted by Permission of the Council.) Extensively Illustrated, John Parsons Earwaker, 1888, Romans, 175 pages. Roman Canterbury, as so far revealed by the work of the Canterbury Excavation Committee , Canterbury Excavation Committee, 1949, History, 16 pages. Roman Silchester the archaeology of a Romano-British town, George C. Boon, 1957, Silchester (England), 245 pages. -

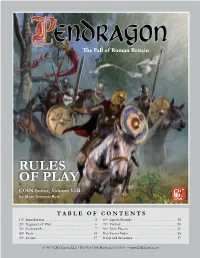

RULES of PLAY COIN Series, Volume VIII by Marc Gouyon-Rety

The Fall of Roman Britain RULES OF PLAY COIN Series, Volume VIII by Marc Gouyon-Rety T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S 1.0 Introduction ............................2 6.0 Epoch Rounds .........................18 2.0 Sequence of Play ........................6 7.0 Victory ...............................20 3.0 Commands .............................7 8.0 Non-Players ...........................21 4.0 Feats .................................14 Key Terms Index ...........................35 5.0 Events ................................17 Setup and Scenarios.. 37 © 2017 GMT Games LLC • P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232 • www.GMTGames.com 2 Pendragon ~ Rules of Play • 58 Stronghold “castles” (10 red [Forts], 15 light blue [Towns], 15 medium blue [Hillforts], 6 green [Scotti Settlements], 12 black [Saxon Settlements]) (1.4) • Eight Faction round cylinders (2 red, 2 blue, 2 green, 2 black; 1.8, 2.2) • 12 pawns (1 red, 1 blue, 6 white, 4 gray; 1.9, 3.1.1) 1.0 Introduction • A sheet of markers • Four Faction player aid foldouts (3.0. 4.0, 7.0) Pendragon is a board game about the fall of the Roman Diocese • Two Epoch and Battles sheets (2.0, 3.6, 6.0) of Britain, from the first large-scale raids of Irish, Pict, and Saxon raiders to the establishment of successor kingdoms, both • A Non-Player Guidelines Summary and Battle Tactics sheet Celtic and Germanic. It adapts GMT Games’ “COIN Series” (8.1-.4, 8.4.2) game system about asymmetrical conflicts to depict the political, • A Non-Player Event Instructions foldout (8.2.1) military, religious, and economic affairs of 5th Century Britain. -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

'J.E. Lloyd and His Intellectual Legacy: the Roman Conquest and Its Consequences Reconsidered' : Emyr W. Williams

J.E. Lloyd and his intellectual legacy: the Roman conquest and its consequences reconsidered,1 by E.W. Williams In an earlier article,2 the adequacy of J.E.Lloyd’s analysis of the territories ascribed to the pre-Roman tribes of Wales was considered. It was concluded that his concept of pre- Roman tribal boundaries contained major flaws. A significantly different map of those tribal territories was then presented. Lloyd’s analysis of the course and consequences of the Roman conquest of Wales was also revisited. He viewed Wales as having been conquered but remaining largely as a militarised zone throughout the Roman period. From the 1920s, Lloyd's analysis was taken up and elaborated by Welsh archaeology, then at an early stage of its development. It led to Nash-Williams’s concept of Wales as ‘a great defensive quadrilateral’ centred on the legionary fortresses at Chester and Caerleon. During recent decades whilst Nash-Williams’s perspective has been abandoned by Welsh archaeology, it has been absorbed in an elaborated form into the narrative of Welsh history. As a consequence, whilst Welsh history still sustains a version of Lloyd’s original thesis, the archaeological community is moving in the opposite direction. Present day archaeology regards the subjugation of Wales as having been completed by 78 A.D., with the conquest laying the foundations for a subsequent process of assimilation of the native population into Roman society. By the middle of the 2nd century A.D., that development provided the basis for a major demilitarisation of Wales. My aim in this article is to cast further light on the course of the Roman conquest of Wales and the subsequent process of assimilating the native population into Roman civil society. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A study of the client kings in the early Roman period Everatt, J. D. How to cite: Everatt, J. D. (1972) A study of the client kings in the early Roman period, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10140/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk .UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM Department of Classics .A STUDY OF THE CLIENT KINSS IN THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE J_. D. EVERATT M.A. Thesis, 1972. M.A. Thesis Abstract. J. D. Everatt, B.A. Hatfield College. A Study of the Client Kings in the early Roman Empire When the city-state of Rome began to exert her influence throughout the Mediterranean, the ruling classes developed friendships and alliances with the rulers of the various kingdoms with whom contact was made. -

Human Rights, Social Welfare, and Greek Philosophy Legitimate

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: H Interdisciplinary Volume 15 Issue 8 Version 1.0 Year 2015 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X Human Rights, Social Welfare, and Greek Philosophy Legitimate Reasons for the Invasion of Britain by Claudius By Tomoyo Takahashi University of California, United States Abstract- In 43 AD, the fourth emperor of Imperial Rome, Tiberius Claudius Drusus, organized his military and invaded Britain. The purpose of this paper is to investigate the legitimate reasons for The Invasion of Britain led by Claudius. Before the invasion, his had an unfortunate life. He was physically distorted, so no one gave him an official position. However, one day, something unimaginable happened. He found himself selected by the Praetorian Guard to be the new emperor of Roma. Many scholars generally agree Claudius was eager to overcome his physical disabilities and low expectations to secure his position as new Emperor in Rome by military success in Britain. Although his personal motivation was understandable, it was not sufficient enough for Imperial Rome to legitimize the invasion of Britain. It is important to separate personal reasons and official reasons. Keywords: (1) roman, (2) britain, (3) claudius, (4) roman emperor, (5) colonies, (6) slavery, (7) colchester, (8) veterans, (9) legitimacy. GJHSS-H Classification: FOR Code: 180114 HumanRightsSocialWelfareandGreekPhilosophyLegitimateReasonsfortheInvasionofBritainbyClaudius Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2015. Tomoyo Takahashi. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Boudicca - Verlauf Und Hintergrund Einer Rebellion Gegen Die Römische Herrschaft Und Ihre Darstellung in Den Quellen

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit Boudicca - Verlauf und Hintergrund einer Rebellion gegen die römische Herrschaft und ihre Darstellung in den Quellen. Verfasserin Katharina Uebel angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 310 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Alte Geschichte und Altertumskunde Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Fritz Mitthof II III Mein besonderer Dank gilt der Universität Wien und insbesondere dem Institut für Alte Geschichte und Altertumskunde und ihren Mitarbeitern, die mich gefördert und unterstützt haben. Ich wurde in die Welt der griechisch-römischen Antike und der Geschichtswissenschaft eingeführt und für die Wissenschaft begeistert. Mein Dank gilt meinem Betreuer Univ.-Prof. Dr. Fritz Mitthof. Von Herzen dank ich meinen Lektoren Dr. Andrea Potz und Dr. Peter Schober für emotionale und fachliche Beratung und Beistand. IV V Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einführung und Charakterisierung der Quellen zu Britannien und dem Boudicca Aufstand 4 1.1. Die britannischen Kelten in der römischen Geschichtsschreibung ............................................. 4 1.2. Werke und Leben des Tacitus und ein kurzer Überblick seiner Meinung zum Boudicca- Aufstand ................................................................................................................................................... 8 1.3. Leben und Werk des Cassius Dio und sein Blick auf den Boudicca-Aufstand ......................... 11 1.4. Die Quellen von Tacitus und Cassius Dio und deren Einfluss