Promoting Intersystem Crossing of Fluorescent Molecule Via Single Functional Group Modification Ran Liu, Xing Gao, Mario Barbatti, Jun Jiang, Guozhen Zhang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lehigh.President.J.Simon.CV.Pdf

John D. Simon Office of the President 28 University Drive Lehigh University Bethlehem, PA 18015 Education B. A. Williams College Williamstown, Massachusetts 1979 M. A. Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts 1981 Ph. D. Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts 1983 Institute for Management in Leadership and Education Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts 2007 Professional Positions 2015- President Lehigh University 2011-2015 Executive Vice President and Provost University of Virginia 2011-2015 Robert C. Taylor Professor University of Virginia 2005-2011 Vice Provost for Academic Affairs Duke University 1999-2004 Chair, Department of Chemistry Duke University 2001-2011 Research Professor in Ophthalmology Duke University Medical Center 1998-2011 George B. Geller Professor Duke University 1999-2011 Professor of Biochemistry Duke University Medical Center 1990-1997 Professor UCSD 1989-1990 Visiting Associate Professor University of Colorado, Boulder 1988-1990 Associate Professor UCSD 1985-1988 Assistant Professor UCSD 1983-1985 Postdoctoral Fellow UCLA (M. A. El-Sayed) Honors and Awards IMP Faculty Award, University of Virginia, 2013 Photon Award, American Society for Photobiology, 2008 William J. Maschke, Jr. Memorial Award, Duke University, 2008 North Carolina ACS Section Distinguished Speaker Award, 2006 Elected Fellow of the American Physical Society, 2003 International Scientist of the Year, International Biographical Centre of Cambridge, England, 2002 Elected Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2000 Hans A. Schaeffer Award, Society of Cosmetic Chemists, 1999 Professor of the Year, Sigma Chi Fraternity, UCSD, 1994 Fresenius Award in Pure and Applied Chemistry, 1992 Camille and Henry Dreyfus Teacher Scholar, 1990-1995 Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellow, 1988-1990 Presidential Young Investigator Award NSF, 1985-1990 Celanese Graduate Fellow, l981-l982 Charles R. -

Intersystem Crossing and Energy Transfer in Charge-Transfer Complexes

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1962 Intersystem Crossing and Energy Transfer in Charge-Transfer Complexes. Nicholas D. Christodouleas Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Christodouleas, Nicholas D., "Intersystem Crossing and Energy Transfer in Charge-Transfer Complexes." (1962). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 770. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/770 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been 63-2764 microfilmed exactly as received CHRIS TODOULEAS, Nicholas D., 1932- INTERSYSTEM CROSSING AND ENERGY TRANS FER IN CHARGE-TRANSFER COMPLEXES. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1962 Chemistry, physical University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. INTERSYSTEM CROSSING AND ENERGY TRANSFER IN CHARGE-TRANSFER COMPLEXES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Chemistry by Nicholas D. Christodouleas University of Athens (Greece), 1956 August, 1962 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to Dr. S. P. McGlynn, who directed this research and who aided me patiently and understandingly. I wish to express my appreciation to Professor H. -

Inverting Singlet and Triplet Excited States Using Strong Light-Matter Coupling

Inverting Singlet and Triplet Excited States using Strong Light-Matter Coupling Elad Eizner1,*, Luis A. Martínez-Martínez2, Joel Yuen-Zhou2, Stéphane Kéna-Cohen1,* 1. Department of Engineering Physics, École Polytechnique de Montréal, Montréal H3C 3A7, QC, Canada. 2. Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, California 92093, United States. KEYWORDS: Exciton-Polaritons, Reverse intersystem crossing, Cavity Quantum Electrodynamics. 1 ABSTRACT In organic microcavities, hybrid light-matter states can form with energies that differ from the bare molecular excitation energies by nearly 1 eV. A timely question, given recent advances in the development of thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials, is whether strong light-matter coupling can be used to invert the ordering of singlet and triplet states and, in addition, enhance reverse intersystem crossing (RISC) rates. Here, we demonstrate a complete inversion of the singlet lower polariton and triplet excited states. We also unambiguously measure the RISC rate in strongly-coupled organic microcavities and find that, regardless of the large energy level shifts, it is unchanged compared to films of the bare molecules. This observation is a consequence of slow RISC to the lower polariton due to the delocalized nature of the state across many molecules and an inability to compete with RISC to the dark exciton reservoir, which occurs at a rate comparable to that in bare molecules. 2 Introduction. In the molecular orbital picture, when an electron is promoted from the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), it can form either an electron-hole state (exciton) with overall singlet (S = 0) or triplet (S = 1) total spin (S). -

Organic Solar Cells: Understanding the Role of Förster

Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 17019-17047; doi:10.3390/ijms131217019 OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Molecular Sciences ISSN 1422-0067 www.mdpi.com/journal/ijms Review Organic Solar Cells: Understanding the Role of Forster¨ Resonance Energy Transfer Krishna Feron 1;2;*, Warwick J. Belcher 1 , Christopher J. Fell 2 and Paul C. Dastoor 1 1 CSIRO Energy Technology, PO Box 330, Newcastle, NSW 2304, Australia; E-Mails: [email protected] (W.J.B.); [email protected] (P.C.D.) 2 Centre for Organic Electronics, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-2-4960-6248; Fax: +61-2-4960-6021. Received: 7 October 2012; in revised form: 3 December 2012 / Accepted: 5 December 2012 / Published: 12 December 2012 Abstract: Organic solar cells have the potential to become a low-cost sustainable energy source. Understanding the photoconversion mechanism is key to the design of efficient organic solar cells. In this review, we discuss the processes involved in the photo-electron conversion mechanism, which may be subdivided into exciton harvesting, exciton transport, exciton dissociation, charge transport and extraction stages. In particular, we focus on the role of energy transfer as described by Forster¨ resonance energy transfer (FRET) theory in the photoconversion mechanism. FRET plays a major role in exciton transport, harvesting and dissociation. The spectral absorption range of organic solar cells may be extended using sensitizers that efficiently transfer absorbed energy to the photoactive materials. The limitations of Forster¨ theory to accurately calculate energy transfer rates are discussed. -

Magnetic Field Effects on Photocurrent and Photovoltaic Processes in Organic Solar Cells

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2008 Magnetic Field Effects on Photocurrent and Photovoltaic Processes in Organic Solar Cells Zhihua Xu University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Materials Science and Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Xu, Zhihua, "Magnetic Field Effects on Photocurrent and Photovoltaic Processes in Organic Solar Cells. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2008. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/540 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Zhihua Xu entitled "Magnetic Field Effects on Photocurrent and Photovoltaic Processes in Organic Solar Cells." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Materials Science and Engineering. Bin Hu, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Jimmy Mays, Roberto S. Benson, Bamin Komami Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice -

Radicals Chapter 4 Photochemistry “The Chemistry of Excited States”

Organic Mechanisms: Radicals Chapter 4 Photochemistry “The Chemistry of Excited States” 1 Photochemistry is the study of what happens when molecules absorb quanta of light (energy). Reactions or changes are generally not spontaneous, so we need to input energy to overcome the activation energy barrier. Often we think more commonly of heating a reaction to make it proceed (thermal initiation), but it also possible for photochemical initiation. Photochemical initiation involves the absorption of a quantum of light by a suitable chromophore (section of a molecule that absorbs the light), and this leads to electronic excitation. So we are going from ground states → electronically excited states. These excited states cannot remain excited for long, and need a way to get rid of the extra energy – either by physical or chemical means (photochemical reactions). 2 Energies 100 kcal/mol = 4.34 eV = 286 nm = 35000 /cm (near UV) nano = 10-9 286 kcal/mol = 12.4 eV = 100 nm = 100000 /cm (far UV) Typical Bond Energies C-H 110 kcal/mol C-C 80 C=C 150 C=O 170 UV light provides sufficient energy to move electrons out of bonding orbitals (electronic excitation). 3 States and their energies Energy levels, rotational and vibrational 4 Jablonski diagram A Jablonski diagram, named after the Polish physicist Aleksander Jabłoński, is a diagram that illustrates the electronic states of a molecule and the transitions between them. The states are arranged vertically by energy and grouped horizontally by spin multiplicity. Radiative transitions are indicated by straight arrows and nonradiative transitions by squiggly arrows. The vibrational ground states of each electronic state are indicated with thick lines, the higher rotational states with thinner lines. -

Singlet Oxygen Generation Using New Fluorene-Based Photosensitizers Under One- and Two-Photon Excitation

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2007 Singlet Oxygen Generation Using New Fluorene-based Photosensitizers Under One- And Two-photon Excitation Stephen James Andrasik University of Central Florida Part of the Chemistry Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Andrasik, Stephen James, "Singlet Oxygen Generation Using New Fluorene-based Photosensitizers Under One- And Two-photon Excitation" (2007). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3065. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3065 SINGLET OXYGEN GENERATION USING NEW FLUORENE-BASED PHOTOSENSITIZERS UNDER ONE- AND TWO-PHOTON EXCITATION by STEPHEN J. ANDRASIK B.S. University of Central Florida, 2001 M.S. University of Central Florida, 2004 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Chemistry in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2007 Major Professor: Kevin D. Belfield © 2007 Stephen J. Andrasik ii ABSTRACT Molecular oxygen in its lowest electronically excited state plays an important roll in the field of chemistry. This excited state is often referred to as singlet oxygen and can be generated in a photosensitized process under one- or two-photon excitation of a photosensitizer. It is particularly useful in the field of photodynamic cancer therapy (PDT) where singlet oxygen formation can be used to destroy cancerous tumors. -

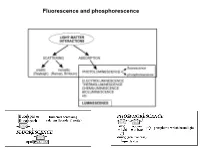

Fluorescence and Phosphorescence Possible De-Excitation Pathways of Excited Molecules

Fluorescence and phosphorescence Possible de-excitation pathways of excited molecules. Various parameters influence the emission of fluorescence. Luminescence: emission of photons from electronically excited states of atoms, molecules and ions. Fluorescence: a process in which a part of energy (UV, Visible) absorbed by a substance is released in the form of light as long as the stimulating radiation is continued. The fluorescence emission took place from a singlet excited states (average lifetime: from <10-10 to 10-7 sec). Phosphorescence: a process in which energy of light absorbed by a substance is released relatively slowly in the form of light. The phosphorescence emission took place from a triplet excited states (average lifetime: from 10-5 to >10+3 sec). S0: fundamental electronic state The Perrin–Jablonski diagram S0, S1, S2: singlet electronic states T1, T2: triplet electronic states Possible processes: ► photon absorption ► vibrational relaxation ► internal conversion ► intersystem crossing ► fluorescence ► phosphorescence ► delayed fluorescence ► triplet–triplet transitions Caracteristic times: absorption: 10-15 s vibrational relaxation: 10-12-10-10 s internal conversion: 10-11-10-9 s intersystem crossing: 10-10-10-8 s lifetime of the excited states: 10-10-10-7 s (fluorescence) lifetime of the excited states:10-6 s (phosphorescence) The vertical arrows corresponding to absorption start from the 0 (lowest) vibrational energy level of S0 because the majority of molecules are in this level at room temperature. Absorption of a photon can bring a molecule to one of the vibrational levels of S1; S2; . : For some aromatic hydrocarbons (naphthalene, anthracene and perylene) the absorption and fluorescence spectra exhibit vibrational bands. -

Intersystem Crossing Processes in Nonplanar Aromatic Heterocyclic Molecules

10490 J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 10490-10499 Intersystem Crossing Processes in Nonplanar Aromatic Heterocyclic Molecules Karin Schmidt,*,† Sergio Brovelli,‡ Veaceslav Coropceanu,† David Beljonne,†,§ Je´roˆme Cornil,†,§ Cristina Bazzini,| Tullio Caronna,| Riccardo Tubino,‡ Francesco Meinardi,‡ Zhigang Shuai,⊥ and Jean-Luc Bre´das*,† School of Chemistry and Biochemistry and Center of Organic Photonics and Electronics, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, Georgia 30332-0400, CNISM e Dipartimento di Scienza dei Materiali, UniVersita` di Milano Bicocca, Via Cozzi 53, I-20125 Milano, Italy, SerVice de Chimie des Mate´riaux NouVeaux, Centre de Recherche en Electronique et Photonique Mole´culaires, UniVersite´ de Mons-Hainaut, B-7000 Mons, Belgium, Dipartimento di Chimica Industriale della Facolta` di Ingegneria, UniVersita` di Bergamo, Viale Marconi 5, I-24044 Dalmine (BG), Italy, and Key Laboratory of Organic Solids, Institute of Chemistry, The Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100080 Beijing, P. R. China ReceiVed: July 5, 2007 A comprehensive study of the photophysical properties of a series of monoaza[5]helicenes is presented on the basis of joint optical spectroscopy and quantum chemistry investigations. The molecules have been characterized by absorption and CW/time-resolved luminescence measurements. All quantities related to spin- orbit-coupling processes, such as intersystem crossing rates and radiative phosphorescence lifetimes, were found to depend strongly on the nitrogen position within the carbon backbone. Density functional theory and semiempirical quantum-chemical methods were used to evaluate the molecular geometries, the characteristics of the excited singlet and triplet states, and the spin-orbit coupling matrix elements. We demonstrate that the magnitude of spin-orbit coupling is directly correlated with the degree of deviation from planarity. -

Direct Triplet Sensitization of Oligothiophene by Quantum Dots

Direct triplet sensitization of oligothiophene by quantum dots Zihao Xu, Emory University Tao Jin, Emory University Yiming Huang, Rice University Karimulla Mulla, Rice University Francesco Evangelista, Emory University Eilaf Egap, Rice University Tianquan Lian, Emory University Journal Title: Chemical Science Volume: Volume 10, Number 24 Publisher: Royal Society of Chemistry: Open Access | 2019-01-01, Pages 6120-6124 Type of Work: Article | Final Publisher PDF Publisher DOI: 10.1039/c9sc01648a Permanent URL: https://pid.emory.edu/ark:/25593/v0zb4 Final published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/c9sc01648a Copyright information: © 2019 The Royal Society of Chemistry. This is an Open Access work distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). Accessed September 28, 2021 1:23 PM EDT Chemical Science View Article Online EDGE ARTICLE View Journal | View Issue Direct triplet sensitization of oligothiophene by quantum dots† Cite this: Chem. Sci.,2019,10,6120 a a b b All publication charges for this article Zihao Xu, Tao Jin, Yiming Huang, Karimulla Mulla, have been paid for by the Royal Society Francesco A. Evangelista, *a Eilaf Egap *b and Tianquan Lian *a of Chemistry Effective sensitization of triplet states is essential to many applications, including triplet–triplet annihilation based photon upconversion schemes. This work demonstrates successful triplet sensitization of a CdSe quantum dot (QD)–bound oligothiophene carboxylic acid (T6). Transient absorption spectroscopy provides direct evidence of Dexter-type triplet energy transfer from the QD to the acceptor without populating the singlet excited state or charge transfer intermediates. -

Investigation of Singlet Fission Solar Cells from Perylene Bis(Phenethylimide)

MSc Chemistry Science for Energy and Sustainability Master Thesis Investigation of singlet fission solar cells from perylene bis(phenethylimide) by Maarten Mennes 10823026 September 2016 54 ECTS Period: October 2015 – September 2016 Examiners: Daily supervisor: prof. dr. A. Polman dr. Bruno Ehrler dr. E. von Hauff Abstract Singlet exciton fission is one of the ways to circumvent the Shockley-Queisser limit. This the- oretical limit is 33.4% for single-junction photovoltaic (PV) devices. By only absorbing high energy photons from the spectrum and subsequently sharing this high excitation energy with one of its neighbors, certain organic molecules offer a way around this limit, and the theoretical max- imum efficiency increases to 45%. Inorganic tandem solar cells suffer from high material costs, and the organic molecules that have shown singlet fission behavior can in principle be cheap. In this work we have explored the organic semiconductor perylene bis(phenethylimide)(PDI). The incorporation of this new material into practical devices would allow for the study of singlet fission in a new material, that could act as an electron acceptor. If this molecule performs sin- glet fission, it would be the first singlet fission molecule that has electron accepting properties, opening a way towards an all-singlet fission solar cell and thereby possibly allow to reduce ther- malization losses even more. In addition, PDI is environmentally stable, as opposed to most conventional singlet fission materials. The devices that were fabricated with the PDI donor 2 showed a Jsc of 0.8mA=cm with low Voc. The devices with PDI as an acceptor, in combination with a PTB7 donor, showed better performance. -

Deciphering the Intersystem Crossing in Near-Infrared BODIPY Photosensitizers for Highly Efficient Photodynamic Therapy

Chemical Science View Article Online EDGE ARTICLE View Journal | View Issue Deciphering the intersystem crossing in near- infrared BODIPY photosensitizers for highly Cite this: Chem. Sci.,2019,10,3096 ffi † All publication charges for this article e cient photodynamic therapy have been paid for by the Royal Society a b c a b of Chemistry Xiaofei Miao,‡ Wenbo Hu,‡ Tingchao He, Haojie Tao, Qi Wang, Runfeng Chen, a Lu Jin,a Hui Zhao,a Xiaomei Lu,b Quli Fan *a and Wei Huangabd Deciphering singlet-to-triplet intersystem crossing (ISC) in organic near-infrared photosensitizers (PSs) is of fundamental importance in the designing of high-performance PSs to boost the clinical usage of photodynamic therapy (PDT). However, in-depth investigations of the ISC dynamics in near-infrared PSs have not been performed to date. Here, systematical investigations of the ISC dynamics in organic near- infrared BODIPY derivatives are presented, in which a multi-channel yet remarkably efficient ISC process is revealed by ultrafast femtosecond transient absorption (fs-TA) spectroscopy and theoretical calculation. The fs-TA verifies an exceptionally enhanced ISC efficiency (FISC ¼ 91%) in iodine- Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. substituted BODIPY (2I-BDP) which is further supported by the calculation results. This endows 2I-BDP Received 30th October 2018 with an ultrahigh singlet oxygen quantum yield (FD ¼ 88%), thus enabling a proof-of-concept application Accepted 17th January 2019 of highly efficient PDT in vivo under ultralow near-infrared light power density (10 mW cmÀ2). The in- DOI: 10.1039/c8sc04840a depth understanding of ISC dynamics in organic near-infrared materials may provide valuable guidance rsc.li/chemical-science in the designing of novel organic theranostic materials for clinical cancer treatment.