Evaluation of Walleye Introductions Into Lakes Burton and Seed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Which Sunfish Is It?

Which Sunfish is It? Grade Level: Upper Elementary Subject Areas: Life science Duration: 45 minutes Next Generation Science Standards: • 4-LS1-1 – Construct an argument that plants and animals have internal and external structures that function to support survival, growth, behavior, and reproduction o Practices of science . Constructing explanations o Cross cutting concepts . Structure and function Common Core State Standards: • ELA/Lit o RI.4-5.4 – Determine the meaning of general or domain specific words or phrases in a text relevant to a grade 4 topic or subject area. • SL.4-5.1 - Engage effectively in a range of collaborative texts, discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with diverse partners on grade appropriate topics and building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly. Objectives: • Students will be able to use a dichotomous key to identify several species of sunfish found in Maryland. • Students will be able to use their knowledge of external fish anatomy to construct their own dichotomous key. Teacher Background: Bluegills are members of the family Centrarchidae or the sunfish family. When many people think of sunfish, they think of bluegills, pumpkinseeds or redbreast sunfish, but in Maryland, this family also includes several other fish that are popular with anglers - largemouth and smallmouth bass, and black and white crappies. This exercise will help students tell the difference between a bass and a bluegill. A dichotomous key is a tool that is usually used to identify living things. The key is called dichotomous (“divided into two parts”) because at each step the user must make a choice between two alternatives, based on some characteristic of the organism to be identified. -

Tennessee Fish Species

The Angler’s Guide To TennesseeIncluding Aquatic Nuisance SpeciesFish Published by the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency Cover photograph Paul Shaw Graphics Designer Raleigh Holtam Thanks to the TWRA Fisheries Staff for their review and contributions to this publication. Special thanks to those that provided pictures for use in this publication. Partial funding of this publication was provided by a grant from the United States Fish & Wildlife Service through the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force. Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency Authorization No. 328898, 58,500 copies, January, 2012. This public document was promulgated at a cost of $.42 per copy. Equal opportunity to participate in and benefit from programs of the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency is available to all persons without regard to their race, color, national origin, sex, age, dis- ability, or military service. TWRA is also an equal opportunity/equal access employer. Questions should be directed to TWRA, Human Resources Office, P.O. Box 40747, Nashville, TN 37204, (615) 781-6594 (TDD 781-6691), or to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office for Human Resources, 4401 N. Fairfax Dr., Arlington, VA 22203. Contents Introduction ...............................................................................1 About Fish ..................................................................................2 Black Bass ...................................................................................3 Crappie ........................................................................................7 -

Prairie Ridge Species Checklist 2018

Prairie Ridge Species Checklist Genus species Common Name Snails Philomycus carolinianus Carolina Mantleslug Gastrocopta contracta Bottleneck Snaggletooth Glyphalinia wheatleyi Bright Glyph Triodopsis hopetonensis Magnolia Threetooth Triodopsis juxtidens Atlantic Threetooth Triodopsis fallax Mimic Threetooth Ventridens cerinoideus Wax Dome Ventridens gularis Throaty Dome Anguispira fergusoni Tiger Snail Zonitoides arboreus Quick Gloss Deroceras reticulatum Gray Garden Slug Mesodon thyroidus White-lip Globe Slug Stenotrema stenotrema Inland Stiltmouth Melanoides tuberculatus Red-rim Melania Spiders Argiope aurantia Garden Spider Peucetia viridans Green Lynx Spider Phidippus putnami Jumping Spider Phidippus audax Jumping Spider Phidippus otiosus Jumping Spider Centipedes Hemiscolopendra marginata Scolopocryptops sexspinosus Scutigera coleoptrata Geophilomorpha Millipedes Pseudopolydesmus serratus Narceus americanus Oxidus gracilis Greenhouse Millipede Polydesmidae Crayfishes Cambarus “acuminatus complex” (= “species C”) Cambarus (Depressicambarus) latimanus Cambarus (Puncticambarus) (="species C) Damselflies Calopteryx maculata Ebony Jewelwing Lestes australis Southern Spreadwing Lestes rectangularis Slender Spreadwing Lestes vigilax Swamp Spreadwing Lestes inaequalis Elegant Spreadwing Enallagma doubledayi Atlantic Bluet Enallagma civile Familiar Bluet Enallagma aspersum Azure Bluet Enallagma exsulans Stream Bluet Enallegma signatum Orange Bluet Ischnura verticalis Eastern Forktail Ischnura posita Fragile Forktail Ischnura hastata Citrine -

Like No Place on Earth

Like no Place on Earth Heaven’s Landing, the Middle of EVERYWHERE! - Mike Ciochetti EVERYWHERE Heaven’s Landing is a residential fly-in community located in the Blue Ridge Mountains of northeast Georgia. Immediately surrounded by the pristine EVERYTHING serenity of the Chattahoochee National Forest, one could easily get the impression that Heaven’s Landing is located in the middle of nowhere. After all, virtually every photograph that you see of Heaven’s Landing shows a 5,200 The Races foot runway surrounded by colorful mountain wilderness. To the contrary, however, Heaven’s Landing is only 3.5 miles from the City of Clayton, Georgia, and very much in the middle of EVERYWHERE! Fall Sweeps A seven-minute drive from Heaven’s Landing brings you to downtown Clayton, which has the best of just about EVERYTHING! Four of the top 100 rated Where to Find Us chefs in the U.S. operate restaurants in Rabun County to the delight of gourmet foodies. Rabun County was named the “Farm to Table Capital of Georgia!” This is a testament to the great relationships the chefs have with the Circus Arts local farms, following the practices of the finest eateries, and the abundant availability of farm fresh organic meats and produce. If you don’t care to dine out, shoppers will delight in the finest supermarkets, farmer’s markets, Mark Your organic food co-op’s and old fashioned local butcher shops that you will find Calendar ANYWHERE! So Heaven’s Landing has your fine dining needs covered, what is there to do Events to work up an appetite? Once again the answer is EVERYTHING! Let’s start with Lake Burton, a renowned 2,735 acre crystal clear mountain lake where Concierge you can water ski, jet ski, fish, or just cruise on your boat and sunbathe in an atmosphere that is pure nirvana. -

Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards ( 1) Purpose. The establishment of water quality standards. (2) W ate r Quality Enhancement: (a) The purposes and intent of the State in establishing Water Quality Standards are to provide enhancement of water quality and prevention of pollution; to protect the public health or welfare in accordance with the public interest for drinking water supplies, conservation of fish, wildlife and other beneficial aquatic life, and agricultural, industrial, recreational, and other reasonable and necessary uses and to maintain and improve the biological integrity of the waters of the State. ( b) The following paragraphs describe the three tiers of the State's waters. (i) Tier 1 - Existing instream water uses and the level of water quality necessary to protect the existing uses shall be maintained and protected. (ii) Tier 2 - Where the quality of the waters exceed levels necessary to support propagation of fish, shellfish, and wildlife and recreation in and on the water, that quality shall be maintained and protected unless the division finds, after full satisfaction of the intergovernmental coordination and public participation provisions of the division's continuing planning process, that allowing lower water quality is necessary to accommodate important economic or social development in the area in which the waters are located. -

TMDL Implementation Plans for Goat Rock Lake

TMDL Implementation Plan for Nottely River, Downstream of Lake Nottely -- Dissolved Oxygen Introduction The portion of the Nottely River downstream of the dam for Nottely Lake, is located near Ivy Log in Union County, a few miles northwest of Blairsville, Georgia. The Nottely Lake dam is operated by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). Reservoir water flows through the turbine generators in the dam to produce hydroelectric power. The water that for such use is taken from the lower (hypolimnion) zone of the Reservoir where the water is naturally lower in dissolved oxygen (D.O.). Plan for Implementation of the TMDL The TMDL for this and seven other low D.O. river segments below dams, was finalized in November, 2000. The designated use for the Nottely River downstream of the dam is for recreation. The applicable water quality standards there for D.O. are a concentration of 5 milligrams per liter (mg/l) as a daily average and a concentration of 4 mg/l as a minimum value. Attainment and maintenance of these two D.O. water quality standards are the goals of this Implementation Plan. The TMDL recommends that the appropriate federal and state agencies work together in developing an implementation strategy to provide higher oxygenated water from these dam releases. The TMDL adds that these strategies may include oxygenation or aeration of the water, redesigned spillways, or other measures, and that ongoing water quality monitoring is needed to monitor progress. The TVA has added compressors and blowers to add air to the water going through the turbines, when D.O. -

Rights of Way Endangered Species Survey for the Northeast Region of Georgia

RIGHTS OF WAY ENDANGERED SPECIES SURVEY FOR THE NORTHEAST REGION OF GEORGIA. The Northeast Region ofGeorgia includes 24 counties: Banks, Barrows, Clarke, Dawson, Elbert, Fannin, Forsyth, Franklin, Greene, Habersham, Hart, Hall, Jackson, Lumpkin, Madison, Morgan, Oconee, Oglethorpe, Rabun, Stephens, Towns, Union, Walton and White. Based on The Georgia Natural Heritage Inventory records, the following plants and plant community locations were searched for on Georgia Power Company rights ofways: Georgia aster - Aster georgianus Dwarfstonecrop - Sedum pusillum Indian olive - Nestronia umbellulua Silky bindweed - Calystegia catesbiana ssp. sericata Smooth purple coneflower - Echinacea laevigata (Federal Endangered) Ginseng - Panax quinquefolius Pipewort - Eriocaulon koemickianum American Milkwort - Pilularia Americana Granite outcrop (shrub, bare rock, lichen) communities There are three maintenance concerns. Two are minor concerns in Walton county with granite outcrops communities. (See Walton county summary) and one in Stephens county with smooth purnle coneflower (See Stephens county summary). Discussion and recommendations: A few ofthe Northeast Region counties are located in the mountains and foothill region ofGeorgia, but most are in the Piedmont. Much of the Georgia mountain region is owned and managed by the United States Forest Service. Georgia Power has large holdings in this area as well and has been involved with protected species (persistent trillium Trillium persistents and the green salamander aneides aeneus) on company lands at Tallulah Gorge, but these species locations are not close to Georgia Power rights ofways so there are no concerns for right ofway maintenance. The majority oflocations in this region, are within the Piedmont province. Due to a long history ofearly European use (and misuse) for settlement, agriculture and logging, the original Piedmont plant communities ofGeorgia have been altered drastically over the past 2 centuries. -

Beginner's Guide to Fishing

Beginner’s Guide to Fishing www.dnr.sc.gov/aquaticed It is my hope that this guide will make your journey into the world of recreational angling (fishin’) uncomplicated, enjoyable and successful. As you begin this journey, I encourage you to keep in mind the words of the 15th century nun Dame Juliana Berner, “Piscator non solum piscatur.” Being a 15th century nun, naturally Dame Juliana tended to write in Latin. This phrase roughly translates to “there is more to fishing than catching fish.” Dame Juliana knows what she’s talking about, as she’s believed to have penned the earliest known volume of sportfishing, the beginners guide of its day, “ A Tretyse of Fysshyne with an Angle.” As you begin to apply the ideas and concepts in our beginners guide, you will start to develop new skills; you will get to exercise your patience; and, most importantly, you will begin to share special experiences with your family and friends. In the early nineties, I can remember sitting in a canoe with my four-year-old daughter on the upper end of Lake Russell fishing for bream with cane poles and crickets. My daughter looked back at me from the front seat of the canoe and said, “Daddy, I sure do hate to kill these crickets, but we got to have bait.” Later, we spent hours together in the backyard perfecting her cast and talking about how to place the bait in just the right spot. We took those new skills to the pond. The first good cast, bait placed like a pro, and a “big bass” hit like a freight train. -

The Savannah River System L STEVENS CR

The upper reaches of the Bald Eagle river cut through Tallulah Gorge. LAKE TOXAWAY MIDDLE FORK The Seneca and Tugaloo Rivers come together near Hartwell, Georgia CASHIERS SAPPHIRE 0AKLAND TOXAWAY R. to form the Savannah River. From that point, the Savannah flows 300 GRIMSHAWES miles southeasterly to the Atlantic Ocean. The Watershed ROCK BOTTOM A ridge of high ground borders Fly fishermen catch trout on the every river system. This ridge Chattooga and Tallulah Rivers, COLLECTING encloses what is called a EASTATOE CR. SATOLAH tributaries of the Savannah in SYSTEM watershed. Beyond the ridge, LAKE Northeast Georgia. all water flows into another river RABUN BALD SUNSET JOCASSEE JOCASSEE system. Just as water in a bowl flows downward to a common MOUNTAIN CITY destination, all rivers, creeks, KEOWEE RIVER streams, ponds, lakes, wetlands SALEM and other types of water bodies TALLULAH R. CLAYTON PICKENS TAMASSEE in a watershed drain into the MOUNTAIN REST WOLF CR. river system. A watershed creates LAKE BURTON TIGER STEKOA CR. a natural community where CHATTOOGA RIVER ARIAIL every living thing has something WHETSTONE TRANSPORTING WILEY EASLEY SYSTEM in common – the source and SEED LAKEMONT SIX MILE LAKE GOLDEN CR. final disposition of their water. LAKE RABUN LONG CREEK LIBERTY CATEECHEE TALLULAH CHAUGA R. WALHALLA LAKE Tributary Network FALLS KEOWEE NORRIS One of the most surprising characteristics TUGALOO WEST UNION SIXMILE CR. DISPERSING LAKE of a river system is the intricate tributary SYSTEM COURTENAY NEWRY CENTRALEIGHTEENMILE CR. network that makes up the collecting YONAH TWELVEMILE CR. system. This detail does not show the TURNERVILLE LAKE RICHLAND UTICA A River System entire network, only a tiny portion of it. -

GEORGIA TROUT FISHING REGULATIONS Trout Season Trout

GEORGIA TROUT FISHING REGULATIONS Trout Season All designated trout waters are now open year round. Trout Fishing Hours • Fishing 24 hours a day is allowed on all trout streams and all impoundments on trout streams except those in the next paragraph. • Fishing hours on Dockery Lake, Rock Creek Lake, the Chattahoochee River from Buford Dam to Peachtree Creek, the Conasauga River watershed upstream of the Georgia-Tennessee state line and Smith Creek downstream of Unicoi dam are 30 minutes before sunrise until 30 minutes after sunset. Night fishing is not allowed. Trout Fishing Rules • Trout anglers are restricted to the use of one pole and line which must be hand held. No other type of gear may be used in trout streams. • It is unlawful to use live fish for bait in trout streams. Seining bait-fish is not allowed in any trout stream. Impoundments On Trout Streams Anglers can: • Fish for fish species other than trout without a trout license on Dockery and Rock Creek lakes. • Fish at night, except on Dockery and Rock Creek lakes. See Trout Fishing Hours for details. Impoundment notes: • If you fish for or possess trout, you must possess a trout license. If you catch a trout and do not possess a trout license you must release the trout immediately. • State park visitors are not required to have a trout license to fish in the impounded waters of the Park. However, those visitors wishing to harvest trout will need to have a trout license in their possession. Delayed Harvest Streams Anglers fishing delayed harvest streams must release all trout immediately and use and possess only artificial lures with one single hook per lure from Nov. -

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Lakes with an Asterisk * Do Not Have Depth Information and Appear with Improvised Contour Lines County Information Is for Reference Only

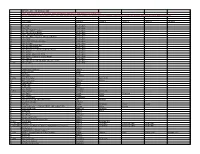

IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Lakes with an asterisk * do not have depth information and appear with improvised contour lines County information is for reference only. Your lake will not be split up by county. The whole lake will be shown unless specified next to name ex (Northern Section) (Near Follette) etc. LAKE NAME COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY COUNTY GL Great Lakes Great Lakes GL Lake Erie Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Port of Toledo) Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Western Basin) Great Lakes GL Lake Erie with Lake Ontario Great Lakes GL Lake Erie (Eastern Section, Mentor to Buffalo) Great Lakes GL Lake Huron Great Lakes GL Lake Huron (w West Lake Erie) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (Northeast) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (South) Great Lakes GL Lake Michigan (w Lake Erie and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Rochester Area) Great Lakes GL Lake Ontario (Stoney Pt to Wolf Island) Great Lakes GL Lake Superior Great Lakes GL Lake Superior (w Lake Michigan and Lake Huron) Great Lakes GL (MI) Lake St Clair Great Lakes AL Cedar Creek Reservoir Franklin AL Deerwood Lake Shelby AL Dog River Mobile AL Gantt Lake Covington AL (GA) Goat Rock Lake * Lee Harris (GA) AL Guntersville Lake Marshall Jackson AL Highland Lake * Blount AL Inland Lake * Blount AL Jordan Lake Elmore AL Lake Gantt * Covington AL (FL) Lake Jackson * Covington Walton (FL) AL Lake Martin Coosa Elmore Tallapoosa AL Lake Mitchell Chilton Coosa AL Lake Tuscaloosa Tuscaloosa AL Lake Wedowee (RL Harris Reservoir) Clay Randolph AL Lake -

Iron Sequestration in Lake Sediments from Artificial Hypolimnetic Oxygenation: Richard B. Russell Reservoir Amanda Elrod Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 12-2007 Iron sequestration in lake sediments from artificial hypolimnetic oxygenation: Richard B. Russell Reservoir Amanda Elrod Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Fresh Water Studies Commons Recommended Citation Elrod, Amanda, "Iron sequestration in lake sediments from artificial hypolimnetic oxygenation: Richard B. Russell Reservoir" (2007). All Theses. 273. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/273 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRON SEQUESTRATION IN LAKE SEDIMENTS FROM ARTIFICIAL HYPOLIMNETIC OXYGENATION: RICHARD B. RUSSELL RESERVOIR A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Biological Sciences by Amanda Kathleen Elrod December 2007 Accepted by: Dr. John J. Hains, Committee Chair Dr. Steven Klaine Dr. Mark Schlautman ABSTRACT The Upper Savannah River watershed has numerous impoundments, and the three largest hydroelectric reservoirs, from north to south, are Hartwell, Richard B. Russell, and J. Strom Thurmond Lakes. During the summer months, these reservoirs undergo thermal and chemical stratification, which results in the formation of cool, hypoxic/anoxic hypolimnia and warm, oxic epilimnion. To maintain fisheries habitat, the United States Army Corps of Engineers operates a hypolimnetic oxygenation system in the forebay of Richard B. Russell Lake. The purpose of this system is to improve the water quality of the releases from Richard B.