Chen.Leetnoobs.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World of Warcraft Online Manual

Game Experience May Change During Online Play WOWz 9/11/04 4:02 PM Page 2 Copyright ©2004 by Blizzard Entertainment. All rights reserved. The use of this software product is subject to the terms of the enclosed End User License Agreement. You must accept the End User License Agreement before you can use the product. Use of World of Warcraft, is subject to your acceptance of the World of Warcraft® Terms of Use Agreement. World of Warcraft, Warcraft and Blizzard Entertainment are trademarks or registered trademarks of Blizzard Entertainment in the U.S. and/or other countries.Windows and DirectX are trademarks or registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the U.S. and/or other countries. Pentium is a registered trademark of Intel Corporation. Power Macintosh is a registered trademark of Apple Computer, Inc. Dolby and the double-D symbol are trademarks of Dolby Laboratory. Monotype is a trademark of Agfa Monotype Limited registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark ® Office and certain other jurisdictions. Arial is a trademark of The Monotype Corporation registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and certain other jurisdictions. ITC Friz Quadrata is a trademark of The International Typeface Corporation which may be registered in certain jurisdictions. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Uses high-quality DivX® Video. DivX® and the DivX® Video logo are trademarks of DivXNetworks, Inc. and are used under license. All rights reserved. AMD, the AMD logo, and combinations thereof are trademarks of Advanced Micro Devices, Inc All ATI product and product feature names and logos, including ATI, the ATI Logo, and RADEON are trademarks and / or registered trademarks of ATI Technologies Inc. -

Meaning-Making in World of Warcraft

Language, Meaning, and Society Volume 2 (2009) Communicative Commodity Forms: Meaning-Making in World of Warcraft Liz ErkenBrack University of Pennsylvania Abstract: World of Warcraft, a “massively multi-player online role playing game,” is a rich dialogic encounter that is mediated by the players through interpersonal footing and reliant on normative discourses. In this paper, I employ a semiotic analysis of the commodity forms within the game to illuminate the motivation and social meaning behind the interactions oriented to these commodity forms in order to deconstruct and understand them as a part of the dialogic meaning-making by the players themselves. Additionally, I explore how a player’s orientation to the game alters the embedded meaning of the commodity forms in my discussion of hypothetical “gold farmers” in Bolivia. The proliferation of literature surrounding the internet and online video games1 is testament to the expanded public interest in these types of virtual technologies. Some authors view the phenomenon with fear, warning that “an epidemic has been growing over the past ten years. What had started out as a simple game has grown into a social dilemma” (Waite, 2007; 2), while others extol the idea that “cyberspace is seen as a utopian space…an alternative to contemporary social reality” (Nayar, 2004; 166). Indeed, as the documentary Second Skin presents, there are individuals who feel they inhabit Azeroth, the online world in which World of Warcraft is based, 1 281,076 returns for a book search of “internet” on Amazon.com and 2, 467 returns on “online video games” http://www.amazon.com/s/ref=sr_nr_i_0?ie=UTF8&rs=&keywords=internet&rh=i%3Aaps%2Ck%3Ainternet%2Ci %3Astripbooks 8 Language, Meaning, and Society Volume 2 (2009) and visit the physical world beyond the computer. -

381 Karlsen 17X24.Pdf (9.567Mb)

Emergent Perspectives on Multiplayer Online Games: A Study of Discworld and World of Warcraft Faltin Karlsen Doctoral thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. Faculty of Humanities, University of Oslo, June 2008. © Faltin Karlsen, 2009 Series of dissertations submitted to the Faculty of Humanities,University of Oslo No. 381 ISSN 0806-3222 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission. Cover: Inger Sandved Anfinsen. Printed in Norway: AiT e-dit AS, Oslo, 2009. Produced in co-operation with Unipub AS. The thesis is produced by Unipub AS merely in connection with the thesis defence. Kindly direct all inquiries regarding the thesis to the copyright holder or the unit which grants the doctorate. Unipub AS is owned by The University Foundation for Student Life (SiO) Acknowledgements Thanks to my supervisor Gunnar Liestøl for constructive and enthusiastic support of my work, from our first discussions about computer games long before this project was initiated, to the final reassuring comments by phone from someplace between Las Vegas and Death Valley. Thanks to my second supervisor Jonas Linderoth for generously accepting my request and for thorough, precise and not least expeditious comments on various drafts during the last phase of my work. I would also like to thank Espen Ytreberg, Ragnhild Tronstad and Terje Rasmussen for reading and commenting on different parts of my thesis. A special thanks to Astrid Lied for introducing me to Discworld back in 1998, and for commenting on and proofreading parts of this thesis. -

DEN ALLVARSAMMA LEKEN Om World of Warcraft Och Läckaget

DEN ALLVARSAMMA LEKEN Om World of Warcraft och läckaget Peder Stenberg Institution för kultur- och medievetenskaper Umeå 2011 Etnologiska skrifter 55 Institutionen för kultur- och medievetenskaper Umeå universitet Responsible publisher under swedish law: the Dean of the Faculty of Humanities Responsible publisher under swedish law: the Dean of the Medical Faculty ThisISBN: work 978 is -protected91-7459- 178by the-1 Swedish Copyright Legislation (Act 1960:729) ISSN: 1103-6516 Etnologiska skrifter ISBN: 12-1234-123-1 Layout: Frans Enmark ISSN:Elektronisk 1234-1234 version tillgänglig på http://umu.diva-portal.org/ Tryck/Printed by: Print & Media. Elektronisk version tillgänglig på http://umu.diva-portal.org/ Tryck/PrintedUmeå, Sverige by: Print 2011 & Media Umeå, Sverige 2011 TACK! Tack till alla er som gjort denna avhandling möjlig: min handledare Alf Arvidsson, min bihandledare Billy Ehn, alla vänner från World of Warcraft, Elin, Julian, Frans, Erik, Elza, Anders, mamma, pappa, Deportees, Jonas, Mattias och alla ni andra som stått ut med mitt ständiga tal om virtuella världar. Jag vill också rikta ett stort tack till alla fantastiska kollegor på institutionen. i INNEHÅLL 1. INLEDNING 1 SYFTE 3 ATT VÄLJA EMPIRI FÖR ONLINEROLLSPEL SOM FORSKNINGSFÄLT 4 METODOLOGISKA PROBLEM OCH REFLEXIVITET 7 AVGRÄNSNING AV MATERIAL OCH ETISKA ÖVERVÄGANDEN 10 OM FORSKARENS FÖRSTA MÖTE MED ETT EXKLUDERANDE FÄLT 12 DEN EXPLICITA FORSKARROLLEN 16 WORLD OF WARCRAFT 2005-2010 17 FORSKNINGSSAMMANHANG 19 DISPOSITION 21 2. OM ONLINEROLLSPELENS FORMELLA BESKAFFENHET 22 SPELET 22 Onlinerollspelen och dess historia 22 Om plats och geografi 24 Den användbara estetiken 25 Datorn och drömmen om den genomskinliga tekniken 27 Narrativ, ontologi och kosmologi 28 Om de sociala nätverken 30 Spelar man eller leker man? 31 OM SKAPANDET AV EN AVATAR 33 Val av genus och virtuellt förkroppsligande 34 Att välja sida i World of Warcraft 35 Om server och dess betydelse 39 Att välja namn 40 Jag och mina avatarer 43 3. -

Transmedia Storytelling in the Warcraft Universe: the Role of Intermediality in Shaping the Warcraft Lore

Transmedia Storytelling in the Warcraft Universe: the Role of Intermediality in Shaping the Warcraft Lore Eszter Barabás A research Paper submitted to the University of Dublin, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Interactive Digital Media 2020 Declaration I have read and I understand the plagiarism provisions in the General Regulations of the University Calendar for the current year, found at: http://www.tcd.ie/calendar I have also completed the Online Tutorial on avoiding plagiarism ‘Ready, Steady, Write’, located at http://tcd-ie.libguides.com/plagiarism/ready-steady-write I declare that the work described in this research Paper is, except where otherwise stated, entirely my own work and has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university. Signed: Eszter Barabás 2020 Permission to lend and/or copy I agree that Trinity College Library may lend or copy this research Paper upon request. Signed: Eszter Barabás 2020 Summary This paper examines the popular franchise known as Warcraft, applying the theory of intermediality to the different mediums that contribute to it, analyzing each of their roles and how intermediality manifests across all platforms. The three established forms of intermediality, that of medial transposition, media combination and intermedial references are used, as well as the concept of transmedia storytelling, considered a fourth type. These categories are first introduced and defined, along with the vast network of media artifacts that contribute to the Warcraft lore. Each consecutive chapter focuses on one form of intermediality, applying it to a few representative works from the Warcraft franchise. -

Being in the World (Of Warcraft): Raiding, Realism, and Knowledge Production in a Massively Multiplayer Online Game

Being in the World (of Warcraft): Raiding, Realism, and Knowledge Production in a Massively Multiplayer Online Game Alex Golub University of Hawaii Anthropological Quarterly, Vol. 83, No. 1, pp. 17–46, ISSN 0003-549. © 2010 by the Institute for Ethnographic Research (IFER) a part of the George Washington University. All rights reserved. Abstract This paper discusses two main claims made about virtual worlds: first, that people become “immersed” in virtual worlds because of their sensorial realism, and second, because virtual worlds appear to be “places” they can be studied without reference to the lives that their inhabitants live in the actual world. This paper argues against both of these claims by using data from an ethnographic study of knowledge production in World of Warcraft. First, this data demonstrates that highly-committed (“immersed”) players of World of Warcraft make their interfaces less sensorially realistic (rather than more so) in order to obtain useable knowledge about the game world. In this case, immersion and sensorial realism may be inversely correlated. Second, their commitment to the game leads them to engage in knowledge-making activities outside of it. Drawing loosely on phenomenology and contemporary theorizations of Oceania, I argue that what makes games truly “real” for players is the extent to which they create collective projects of action that people care about, not their imitation of sensorial qualia. Additionally, I argue that while purely in-game research is methodologically legitimate, a full account of member’s lives must study the articulation of in-game and out-of-game worlds and trace people’s engagement with virtual worlds across multiple domains, some virtual and some actual. -

Warcraft® III: Reforged Is Now Live

To Battle! Warcraft® III: Reforged Is Now Live January 28, 2020 Experience a pivotal period in the Warcraft saga through an epic single-player story spanning over 60 missions, and test yourself in battle online with Warcraft III’s timeless competitive multiplayer gameplay This full-scale modernization of Blizzard Entertainment’s real-time strategy classic features thoroughly overhauled graphics, a revamped World Editor, and full Battle.net® integration IRVINE, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Jan. 28, 2020-- Relive some of the most epic moments in Azeroth’s history with Warcraft® III: Reforged, a thorough reimagining of Blizzard’s groundbreaking real-time strategy game. Combining the original Warcraft III: Reign of Chaos® and its award- winning expansion, The Frozen Throne®, Warcraft III: Reforged re-envisions a pivotal period in the Warcraft saga, with a robust single-player story spanning seven individual campaigns, a top-to-bottom overhaul of its graphics and sound, up-to-date social and matchmaking features via Blizzard’s Battle.net® online-gaming service, and a revamped World Editor to power the community’s creations. This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20200128005855/en/ Players will revisit the Warcraft III story in Reforged, with over 60 missions to experience from the eyes of four factions—the mighty Orcs, the noble Humans, the ancient Night Elves, and the insidious Undead. Players will witness firsthand key moments in Azeroth’s history, from the Burning Legion’s invasion to the ascension of the Lich King, and learn the origins of iconic Warcraft characters like Thrall, Jaina Proudmoore, Sylvanas Windrunner, Illidan Stormrage, and others. -

Why the Humans Are White: Fantasy, Modernity, and the Rhetorics Of

WHY THE HUMANS ARE WHITE: FANTASY, MODERNITY, AND THE RHETORICS OF RACISM IN WORLD OF WARCRAFT By CHRISTOPHER JONAS RITTER A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of English MAY 2010 To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of CHRISTOPHER JONAS RITTER find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. __________________________________ Victor Villanueva, Ph.D., Chair __________________________________ Patricia Freitag Ericsson, Ph.D. __________________________________ Jason Farman, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Greatest thanks go to my family guild, without whom I would never have played WoW for so long (or even in the first place, possibly): Dan Crockett, Annie Ritter, Dave Ritter, Betsy Ritter, and Peter Ritter. To my committee: Victor Villanueva, Patty Ericsson, and Jason Farman. Without your open- mindedness and encouragement, I would have succumbed to the derision of the Luddites and avoided studying what I love. To my colleagues/friends/professors at WSU, who helped me work out my ideas about this subject as they were born in several different seminars. Especially: Shawn LameBull, Rachael Shapiro, Hannah Allen, and Kristin Arola. To Jeff Hatch for his expertise with the architecture stuff. To The Gang, who helped me work out my ideas over beers: Pat Johnson, Sarah Bergfeld, Scott McMurtrey, Jim Haendiges, and Gage Lawhon. To my dad, Tom Ritter, for introducing me to Pong in like 1985 and indirectly putting me on the path that led me here. To Blizzard, not only for making a game that‘s kept me happy for approximately six times longer than any game had done previously; but more importantly, for providing the context and occasion for me to maintain long-distance relationships with people I love. -

World of Warcraft: Legion Hardcover Blank Sketchbook Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WORLD OF WARCRAFT: LEGION HARDCOVER BLANK SKETCHBOOK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK . Blizzard Entertainment | 192 pages | 17 May 2016 | Insight Editions | 9781608876877 | English | San Rafael, United States World of Warcraft: Legion Hardcover Blank Sketchbook PDF Book The design needs to match the idea. Dropshipping Fabian Siegler. If the price is too high, you may want to consider buying in bulk or waiting until there is a promotion on the item. The Art of World of Warcraft - Monatskalender. Russo Cissp-Issap Ciso. Pre-order - out 31 Jan As the Swarm boils in chaotic uncertainty, Arcturus Mengsk has seized this opportunity to bolster his Dominion forces. World of Warcraft: Poster Collection. Dropshipping Fabian Siegler. The Illidari Hardcover Journal By nooah Polygonmonster says:. You can submit as many entries as you like, but only submit new work that you created for this contest! Solo projects only. Russo Cissp-Issap Ciso. Keep in mind the character is optional. Jake Ramsey -- an unassuming, yet talented archaeologist -- has been given the chance of a lifetime. Tags: illidan stormrage, world of warcraft, wow, minimalist, warcraft, games, videogames, minimal, purple, green. Published: May 17, Illidan Hardcover Journal By Snoweflake. Warm yourself by the fire and hear the story of how Hearthstone came to be, growing from a small-team project to the worldwide success that it is today with more than 50 million players. Hours of Play:. Kubernetes Handbook Stephen Fleming. Russo Cissp-Issap Itilv3. When you shop for a new warcraft legion, make sure to read through the product descriptions. As long as the models are created from scratch by you and not taken from the game in any shape or form. -

Copyrighted Material

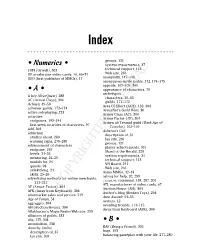

35_752738 bindex.qxp 11/2/05 7:36 PM Page 319 Index groups, 121 • Numerics • system requirements, 37 1984 (Orwell), 303 technical support, 113 3D accelerator video cards, 16, 66–71 Web site, 266 3DO (first publisher of MMGs), 17 anonymity, 147–148 anonymous-invite guilds, 172, 174–175 appeals, 107–109, 304 • A • appearance of characters, 79 archetypes A key (EverQuest), 288 characters, 80–83 AC (Armor Class), 304 guilds, 171–172 Achaea, 49–50 Area Of Effect (AOE), 133, 304 achiever guilds, 172–174 ArenaNet’s Guild Wars, 36 active roleplaying, 223 Armor Class (AC), 304 activities Armor Factor (AF), 304 endgames, 192–194 Armyn ab Treanid guild (Dark Age of first-week activities of characters, 97 Camelot), 162–169 add, 304 Asheron’s Call addiction description of, 31 studies about, 280 fan site, 269 warning signs, 278–280 groups, 121 advancement of characters player achievements, 301 endgame, 190 Shard of the Herald, 228 levels, 24–26 system requirements, 31 mentoring, 24–25 technical support, 113 models for, 24 VN Board, 291 quests, 98 Web site, 266 sidekicking, 24 Asian MMGs, 42–43 skills, 25–26 asking for help, 92, 289 advertising methods for online merchants, /assist command, 134, 287, 304 211–212 ATI, manufacturer of video cards, 67 AF (Armor Factor), 304 COPYRIGHTEDAuction MATERIAL House (AH), 304 AFK (Away from Keyboard), 304 Author’s blog (Broken Toys), 294 aftermarket sales and service, 219 Auto Assault, 54–55 Age of Conan, 54 avatars, 12 agg/aggro, 304 avoiding trouble, 114–115 AH (Auction House), 304 Away from Keyboard (AFK), 304 Allakhazam’s Magic Realm Web site, 293 alliances of guilds, 183 alts, 125, 304 • B • ammunition, 238 Anarchy Online BAF (Bring a Friend), 305 description of, 37 bags, 103 fan site, 269 balancing gameplay with your life, 277–280 35_752738 bindex.qxp 11/2/05 7:36 PM Page 320 320 Massively Multiplayer Games For Dummies Baldur’s Gate, 24 Bring a Friend (BAF), 305 banker, 181 broadband Internet access, 63–64 banking, 204 Broken Toys blog, 294 banks, 199, 202 BRT (Be Right There), 306 Baron Geddon monster (World of Bruce, Walter R. -

Download Warcraft: Lord of the Clans Free Ebook

WARCRAFT: LORD OF THE CLANS DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Christie Golden | 278 pages | 01 Dec 2016 | Blizzard Entertainment | 9780989700115 | English | Irvine, United States Warcraft Adventures: Lord of the Clans With this one, I just couldn't. You throw Durotan into this mix Blackmoore secretly raised the orcling Thrall within the confines of his prison fortress Durnholde. Award-winning author Christie Golden has written over thirty novels and several Warcraft: Lord of the Clans stories in the fields of science fiction, fantasy and horror. He held it aloft with seeming ease, then brandished it at Thrall. February 14, That's how pivotal it is to the entire world of Azeroth. Golden is a outstanding writer, I never Warcraft: Lord of the Clans the wow into reading and I don't know if it's her writing or the story but now I love to read. It's like watching Jackson's Lord of the Rings trilogy and then switching on The Hobbit animated movie. Every twist showed Thrall's personality grow and shape. She deserved more than she actually got. Apr 11, Ken Badertscher rated it it was amazing. Very character driven, which I enjoyed. Other books in the series. Really well-written insight into Thrall's past, psyche, and what drives his need for leadership. He remarked, "It's one thing to have a bunch of cool stills, and it's another thing to have Warcraft: Lord of the Clans fifteen-minute short to show them. Hardcore Gaming They apparently would have been killed by an intense bright light, causing their flesh to melt. -

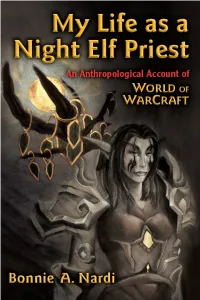

My Life As a Night Elf Priest Technologies of the Imagination New Media in Everyday Life Ellen Seiter and Mimi Ito, Series Editors

My Life as a Night Elf Priest technologies of the imagination new media in everyday life Ellen Seiter and Mimi Ito, Series Editors This book series showcases the best ethnographic research today on engagement with digital and convergent media. Taking up in-depth portraits of different aspects of living and growing up in a media-saturated era, the series takes an innovative approach to the genre of the ethnographic monograph. Through detailed case studies, the books explore practices at the forefront of media change through vivid description analyzed in relation to social, cultural, and historical context. New media practice is embedded in the routines, rituals, and institutions—both public and domes- tic—of everyday life. The books portray both average and exceptional practices but all grounded in a descriptive frame that renders even exotic practices understandable. Rather than taking media content or technology as determining, the books focus on the productive dimensions of everyday media practice, particularly of children and youth. The emphasis is on how specific communities make meanings in their engagement with convergent media in the context of everyday life, focus- ing on how media is a site of agency rather than passivity. This ethnographic approach means that the subject matter is accessible and engaging for a curious layperson, as well as providing rich empirical material for an interdisciplinary scholarly community examining new media. Ellen Seiter is Professor of Critical Studies and Stephen K. Nenno Chair in Television Studies, School of Cinematic Arts, University of Southern California. Her many publications include The Internet Playground: Children’s Access, Entertainment, and Mis-Education; Television and New Media Audiences; and Sold Separately: Children and Parents in Consumer Culture.