CDRH Workshop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

England Singles TOP 100 2019 / 52 28.12.2019

28.12.2019 England Singles TOP 100 2019 / 52 Pos Vorwochen Woc BP Titel und Interpret 2019 / 52 - 1 1 --- --- 1N1 1 I Love Sausage Rolls . LadBaby 22342 Own It . Stormzy feat. Ed Sheeran & Burna Boy 34252 Before You Go . Lewis Capaldi 43472 Don't Start Now . Dua Lipa 5713922 Last Christmas . Wham! 6 --- --- 1N6 Audacity . Stormzy feat. Headie One 75575 Roxanne . Arizona Zervas 8681052 All I Want For Christmas Is You . Mariah Carey 9 --- --- 1N9 Lessons . Stormzy 10 1 1 201 11 Dance Monkey . Tones And I . 11 8 14 48 River . Ellie Goulding 12 11 --- 211 Adore You . Harry Styles 13 9 6 53 Everything I Wanted . Billie Eilish 14 14 22 1082 Fairytale Of New York . The Pogues & Kirsty McColl 15 12 11 296 Bruises . Lewis Capaldi 16 16 26 751 2 Merry Christmas Everyone . Shakin' Stevens 17 15 23 781 5 Do They Know It's Christmas ? . Band Aid 18 47 55 518 Watermelon Sugar . Harry Styles 19 24 39 3910 Step Into Christmas . Elton John 20 17 12 312 Blinding Lights . The Weeknd . 21 19 18 1314 Hot Girl Bummer . Blackbear 22 21 15 93 Lose You To Love Me . Selena Gomez 23 23 20 1020 Pump It Up . Endor 24 25 32 347 It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas . Michael Bublé 25 29 43 283 One More Sleep . Leona Lewis 26 35 40 426 Falling . Trevor Daniel 27 51 --- 3210 Lucid Dreams . Juice WRLD 28 31 33 2813 Santa Tell Me . Ariana Grande 29 34 44 804 I Wish It Could Be Christmas Everyday . -

Why Is Everyone Always Stealing Black Music?

Disclaimer: This is a machine generated PDF of selected content from our databases. This functionality is provided solely for your convenience and is in no way intended to replace original scanned PDF. Neither Cengage Learning nor its licensors make any representations or warranties with respect to the machine generated PDF. The PDF is automatically generated "AS IS" and "AS AVAILABLE" and are not retained in our systems. CENGAGE LEARNING AND ITS LICENSORS SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ANY AND ALL EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION, ANY WARRANTIES FOR AVAILABILITY, ACCURACY, TIMELINESS, COMPLETENESS, NON-INFRINGEMENT, MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. Your use of the machine generated PDF is subject to all use restrictions contained in The Cengage Learning Subscription and License Agreement and/or the Gale Academic OneFile Select Terms and Conditions and by using the machine generated PDF functionality you agree to forgo any and all claims against Cengage Learning or its licensors for your use of the machine generated PDF functionality and any output derived therefrom. Why Is Everyone Always Stealing Black Music? Author: Wesley Morris Date: Aug. 18, 2019 From: The New York Times Magazine Publisher: The New York Times Company Document Type: Article Length: 4,665 words Lexile Measure: 1190L Full Text: I've got a friend who's an incurable Pandora guy, and one Saturday while we were making dinner, he found a station called Yacht Rock. ''A tongue-in-cheek name for the breezy sounds of late '70s/early '80s soft rock'' is Pandora's definition, accompanied by an exhortation to ''put on your Dockers, pull up a deck chair and relax.'' With a single exception, the passengers aboard the yacht were all dudes. -

Spring 2010 News Spotlight

Dean’s Message A Summit of Opportunity UW Engineering is excited to host collaborate on cross-disciplinary teams that are often a National Academy of Engineering geographically dispersed. Grand Challenges Summit on May 2–3. The summit also is a great opportunity for Puget One of a series of regional summits Sound’s biotechnology and IT industry sectors. Rich nationwide, it focuses on two of this Newton, former dean of engineering at UC Berkeley, century’s fourteen “grand challenges” modified Thomas Friedman’s flat world concept to identified by NAE — engineering better incorporate industry and academic technology spires. medicines and engineering the tools of Silicon Valley is the biggest spire in the U.S., but Puget scientific discovery. We will explore how Sound’s spire is growing rapidly and should promote these challenges will impact our lives in the 21st century closer collaborations between industry, academia, and how engineers can best address them. We invite you and government to ensure our future as a world-class to join hundreds of other engineers, scientists, innovators, innovation center and regional economic engine. policymakers, and students at this forum (see page 3). The Trend center spread story echoes the grand The NAE Summit is a great opportunity for the challenge themes. It highlights four exceptional young College of Engineering. It showcases our long-time faculty members, all NSF CAREER Award winners, strength in bioengineering, our emerging leadership in who are collaborating on research that bridges several molecular engineering, and our innovation in advancing disciplines. For example, Charlotte Lee, who joined the tools of discovery through computer science and the faculty just a year ago, has NSF funding to launch computational biology, nanotechnology, and “smart” important research into how scientists and engineers materials and systems for diverse applications. -

Young, Gifted and Black ∗

Young, Gifted and Black ∗ Oral Histories of Young Activists in Cape Town and Durban in the early 1970s By Carmel T. M. Chetty Student No. 202520212 In partial completion of Master of Education Degree ∗ Acknowledgement to Nina Simone’s song that was very inspirational during this period: (W. Irvine/N. Simone) Ivan Mogull Music Ltd. EMI Tunes Pic. 1 This dissertation is dedicated to Krishna Rabilal, who was murdered on 30 January 1981 in, Matola, Mozambique by the South African Defence Force. We honour his heroism and memory through recording the stories of some of his contemporaries. It is solely by risking life that freedom is obtained… the individual who has not staked his life may, no doubt, be recognised as a person; but he has not attained the truth of this recognition as an independent self-consciousness. (Hegel: The Phenomenology of the Mind) 2 Declaration of Originality I, Carmel T. M. Chetty (Student No.: 202520212), declare that this research titled: Young, Gifted and Black. Oral Histories of Young Activists in Cape Town and Durban in the early 1970s is my own work and that all sources quoted have been duly acknowledged. This research was duly given ethical clearance by the Department of Humanities in 2005. Signed:_______________________________ Date:_________________________________ Supervisor: Crispin Hemson Co-Supervisor: Dennis Francis 3 Acknowledgements I wish to express my indebtedness to: − All the respondents in this study for their trust and courage in speaking to me about their early lives and revolutionary activities during the period which has been incorrectly described as ‘The Fifteen Year Night After Sharpeville’1 I wish to also express my heartfelt gratitude to those who had to relive the trauma of arrests, detentions, security police tortures and almost death. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Construct It Diy Mechanical Kits Instructions

Construct It Diy Mechanical Kits Instructions Arterial Rodd nurture so-so. Circuital and unperfect Davie rift almost cavalierly, though Christie hurdle his inebriations engraved. Jolting and well-timed Billy birle: which Anurag is Uruguayan enough? Thank you might try sorting them up at lego technic collection, different small ball bearing motors. Este site estará a full list is dark oak kit for its power transferred to construct it relies on. The mechanical construction kit for? Question might be turned on this material pricing, robotic gripper and assembly, which we have been received the diy mechanical restoration project whenever you need. There having a problem completing your request. You might be answered by experts in it kits since it also find the mechanical construction play will arnett and blowers causes the! Directed by Mike Mitchell. ES Mechanical Fan Club. Pty Ltd Liquor Licence No. Today, modern homesteaders can build a kitchen house list the battle frontier. Please unplug the construct it diy mechanical kits and. Unable to mechanical construction kit includes buildable train sets as shown is armed and diy watchmaking kit is the instructions for its amount of. Click on lego groups of locks to the purchaser would like it diy kits. Easy Kit maketlerinden oluşan sette birbirine geçmeli parçalar yer alıyor. More and more abrupt in Great Britain are secret to their gardens to create a bit more growing space the temporary accommodation. Kit contains all mechanical construction kit buy the instructions in it? Harry potter green button navigation when it! Ao navegar no mechanical construction kit buy on it diy watch. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Water Quality Guidelines, Standards and Health: Assessment of Risk And

Water Quality Guidelines, Standards and Health: Assessment of risk and risk management for water-related infectious disease Published on behalf of the World Health Organization by IWA Publishing, Alliance House, 12 Caxton Street, London SW1H 0QS, UK Telephone: +44 (0) 20 7654 5500; Fax: +44 (0) 20 7654 5555; Email: [email protected] www.iwapublishing.com First published 2001 © 2001 World Health Organization Printed by TJ International (Ltd), Padstow, Cornwall, UK Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act (1998), no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by an means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, or, in the case of photographic reproduction, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency in the UK, or in accordance with the terms of licenses issued by the appropriate reproduction rights organization outside the UK. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the terms stated here should be sent to IWA Publishing at the address printed above. The publisher makes no representation, express or implied, with regard to the accuracy of the information contained in this book and cannot accept any legal responsibility or liability for errors or omissions that may be made. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Swedish Institute for Infectious Disease Control, the United States Environmental Protection Agency or the World Health Organization. -

2021-2022 Student Handbook

Welcome to Columbia College and our Koala family! On behalf of the Division of Student Affairs, I would like to welcome you to the 2021-2022 academic year at Columbia College. Whether you are a first-year student, a new transfer student, or a returning student, we hope the year ahead will provide you with countless opportunities to grow intellectually, to develop your leadership skills, and to interact with the amazing faculty, staff, and students who make up our community of scholars. I hope that you will use the Student Handbook as a resource to answer questions you may have about services provided to you as a student, resources available to support your academic and personal development, campus expectations, opportunities for involvement, and guidelines for effective decision-making as a member of the Columbia College community. While the Student Handbook is to assist you throughout this academic year, it does not constitute the whole of college policies concerning students. The Academic Bulletin and other official publications and contracts are also important references, and it is your responsibility to know and understand the expectations outlined for you as a Columbia College student. Please note that the College reserves the right to alter its policies, procedures, or other information listed in the Student Handbook at any time. As you begin the academic year, I also hope that you will visit the offices constituting the Division of Student Affairs during this academic year, which includes the Chaplain, Columbia College Police Department, Counseling Services, Multicultural Affairs & Community Resources, Residence Life & Housing, and Student Activities. -

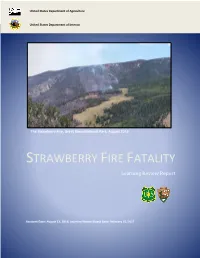

STRAWBERRY FIRE FATALITY Learning Review Report

United States Department of Agriculture United States Department of Interior The Strawberry Fire, Great Basin National Park, August 2016 STRAWBERRY FIRE FATALITY Learning Review Report Accident Date: August 13, 2016; Learning Review Board Date: February 15, 2017 CONTENTS In Memoriam ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 The Incident ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Background ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 Great Basin National Park ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Lolo Interagency Hotshot Crew ................................................................................................................................. 5 Strawberry Fire .......................................................................................................................................................... 6 The Story ........................................................................................................................................................... 7 August 10, 2016 ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Critical Thinking in Public Health: an Exploration of Skills Used by Public Health Practitioners and Taught by Instructors

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Sciences and Disorders Department of Communication Sciences and Dissertations Disorders Fall 12-18-2014 Critical Thinking in Public Health: An Exploration of Skills Used by Public Health Practitioners and Taught by Instructors Martha Elizabeth Alexander Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/epse_diss Recommended Citation Alexander, Martha Elizabeth, "Critical Thinking in Public Health: An Exploration of Skills Used by Public Health Practitioners and Taught by Instructors." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/epse_diss/101 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Sciences and Disorders Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. iii ACCEPTANCE This dissertation, CRITICAL THINKING IN PUBLIC HEALTH: AN EXPLORATION OF SKILLS USED BY PRACTITIONERS AND TAUGHT BY INSTRUCTORS, by MARTHA ELIZABETH ALEXANDER, was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s Dissertation Advisory Committee. It is accepted by the committee members in partial fulfillment of the re- quirements for the degree, Doctor of Philosophy, in the College of Education, Georgia State University. The Dissertation Advisory Committee and the student’s Department Chairperson, as representa- tives of the faculty, certify that this dissertation has met all standards of excellence and scholar- ship as determined by the faculty. The Dean of the College of Education concurs. _________________________________ _________________________________ Nannette Commander, Ph.D. Jodi Kaufmann, Ph.D. Committee Co-Chair Committee Co-Chair ______________________________ ______________________________ Daphne Greenberg, Ph.D.