Crime and Popular Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television Has Long Upheld an Unspoken Rule: a Female Character May Be Beautiful Or Angry, but Never Both

PRETTY HURTS Television has long upheld an unspoken rule: A female character may be beautiful or angry, but never both. A handful of new shows prove that rules were made to be broken BY JULIA COOKE Shapely limbs swollen and wavering under longer dependent on men to be effective.” Woodley’s Jane runs hard and fast, flashing water, lipstick wiped off a pale mouth with a These days, injustice—often linked to the back to scenes of her rape and packing a gun in yellow sponge, blonde bangs caught in the zip- tangled ramifications of a heroine’s beauty— her purse to meet with a man who might be the per of a body bag: Kristy Guevara-Flanagan’s gives women license to take all sorts of juicy perpetrator. Their anger is nuanced, caused by 2016 short film What Happened to Her collects actions that are far more interesting than a range of situations, and on-screen they strug- images of dead women in a 15-minute montage killing. On Marvel’s Jessica Jones, it’s fury at gle to tame it into something else: self-defense, culled mostly from crime-based television dra- being raped and manipulated by the evil Kil- loyalty, grudges, power, career. mas. Throughout, men stand murmuring over grave that spurs the protagonist to become the The shift in representation aligns with the beautiful young white corpses. “You ever see righteously bitchy superhero she’s meant to increasing number of women behind cameras something like this?” a voice drawls. be. When her husband dumps her for his sec- in Hollywood. -

English, French, and Spanish Colonies: a Comparison

COLONIZATION AND SETTLEMENT (1585–1763) English, French, and Spanish Colonies: A Comparison THE HISTORY OF COLONIAL NORTH AMERICA centers other hand, enjoyed far more freedom and were able primarily around the struggle of England, France, and to govern themselves as long as they followed English Spain to gain control of the continent. Settlers law and were loyal to the king. In addition, unlike crossed the Atlantic for different reasons, and their France and Spain, England encouraged immigration governments took different approaches to their colo- from other nations, thus boosting its colonial popula- nizing efforts. These differences created both advan- tion. By 1763 the English had established dominance tages and disadvantages that profoundly affected the in North America, having defeated France and Spain New World’s fate. France and Spain, for instance, in the French and Indian War. However, those were governed by autocratic sovereigns whose rule regions that had been colonized by the French or was absolute; their colonists went to America as ser- Spanish would retain national characteristics that vants of the Crown. The English colonists, on the linger to this day. English Colonies French Colonies Spanish Colonies Settlements/Geography Most colonies established by royal char- First colonies were trading posts in Crown-sponsored conquests gained rich- ter. Earliest settlements were in Virginia Newfoundland; others followed in wake es for Spain and expanded its empire. and Massachusetts but soon spread all of exploration of the St. Lawrence valley, Most of the southern and southwestern along the Atlantic coast, from Maine to parts of Canada, and the Mississippi regions claimed, as well as sections of Georgia, and into the continent’s interior River. -

Judges As Film Critics: New Approaches to Filmic Evidence

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 37 2004 Judges As Film Critics: New Approaches To Filmic Evidence Jessica M. Silbey Foley Hoag L.L.P. Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Evidence Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Litigation Commons Recommended Citation Jessica M. Silbey, Judges As Film Critics: New Approaches To Filmic Evidence, 37 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 493 (2004). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol37/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUDGES AS FILM CRITICS: NEW APPROACHES TO FILMIC EVIDENCE Jessica M. Silbey* This Article exposes internalcontradictions in case law concerning the use and ad- missibility of film as evidence. Based on a review of more than ninety state and federal cases datingfrom 1923 to the present, the Article explains how the source of these contradictionsis the frequent miscategorizationoffilm as "demonstrativeevi- dence, "evidence that purports to illustrate other evidence, ratherthan to be directly probative of some fact at issue. The Articlefurtherdemonstrates how these contradic- tions are based on two venerablejurisprudential anxieties. One is the concern about the growing trend toward replacing the traditionaltestimony of live witnesses in court with communications via video and film technology. -

The Current Status and Issues Surrounding Native Title in Regional Australia

284 Australasian Journal of Regional Studies, Vol. 24, No 3, 2018 NEW DIMENSIONS IN LAND TENURE – THE CURRENT STATUS AND ISSUES SURROUNDING NATIVE TITLE IN REGIONAL AUSTRALIA Jude Mannix PhD Candidate, Science and Engineering Faculty, School of Civil Engineering and Built Environment, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland, 4000, Australia. Email: [email protected]. Michael Hefferan Emeritus Professor, c/- Science and Engineering Faculty, School of Civil Engineering and Built Environment, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland, 4000, Australia. Email: [email protected]. ABSTRACT: The acquisition and use of real property is fundamental to practically all types of resource and infrastructure projects. The success of those activities is based, in no small way, on the reliability of the underlying tenure and land management systems operating across all Australian states and territories. Against that background, however, the historic Mabo (1992) decision gave recognition to Indigenous land rights and the subsequent enactment of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth.) (NTA) ushered in an emerging and complex new aspect of property law. While receiving wide political and community support, these changes have had a significant effect on those long-established tenure systems. Further, it has only been over time, as diverse property dealings have been encountered, that the full implications of the new legislation and its operations have become clear. Regional areas are more likely to encounter native title issues than are urban environments due, in part, to the presence of large scale agricultural and pastoral tenures and of significant areas of un-alienated crown land, where native title may not have been extinguished. -

Civil Trials: a Film Illusion?

Fordham Law Review Volume 85 Issue 5 Article 3 2017 Civil Trials: A Film Illusion? Taunya L. Banks University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Civil Law Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Taunya L. Banks, Civil Trials: A Film Illusion?, 85 Fordham L. Rev. 1969 (2017). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol85/iss5/3 This Colloquium is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CIVIL TRIALS: A FILM ILLUSION? Taunya Lovell Banks* INTRODUCTION The right to trial in civil cases is enshrined in the U.S. Constitution1 and most state constitutions.2 The lack of a provision for civil jury trials in the original draft of the Constitution “almost derailed the entire project.”3 According to the French social scientist Alexis de Tocqueville, the American jury system is so deeply engrained in American culture “that it turns up in and structures even the sheerest forms of play.”4 De Tocqueville’s observation, made in the early nineteenth century, is still true today. Most people, laypersons and legal professionals alike, consider trials an essential component of American democracy. In fact, “the adversarial structure is one of the most salient cultural features of the American legal system. -

Scriptedpifc-01 Banijay Aprmay20.Indd 2 10/03/2020 16:54 Banijay Rights Presents… Bäckström the Hunt for a Killer We Got This Thin Ice

Insight on screen TBIvision.com | April/May 2020 Television e Interview Virtual thinking The Crown's Andy Online rights Business Harries on what's companies eye next for drama digital disruption TBI International Page 10 Page 12 pOFC TBI AprMay20.indd 1 20/03/2020 20:25 Banijay Rights presents… Bäckström The Hunt For A Killer We Got This Thin Ice Crime drama series based on the books by Leif GW Persson Based on a true story, a team of police officers set out to solve a How hard can it be to solve the world’s Suspense thriller dramatising the burning issues of following the rebellious murder detective Evert Bäckström. sadistic murder case that had remained unsolved for 16 years. most infamous unsolved murder case? climate change, geo-politics and Arctic exploitation. Bang The Gulf GR5: Into The Wilderness Rebecka Martinsson When a young woman vanishes without a trace In a brand new second season, a serial killer targets Set on New Zealand’s Waiheke Island, Detective Jess Savage hiking the famous GR5 trail, her friends set out to Return of the riveting crime thriller based on a group of men connected to a historic sexual assault. investigates cases while battling her own inner demons. solve the mystery of her disappearance. the best-selling novels by Asa Larsson. banijayrights.com ScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay AprMay20.indd 2 10/03/2020 16:54 Banijay Rights presents… Bäckström The Hunt For A Killer We Got This Thin Ice Crime drama series based on the books by Leif GW Persson Based on a true story, a team of police officers set out to solve a How hard can it be to solve the world’s Suspense thriller dramatising the burning issues of following the rebellious murder detective Evert Bäckström. -

ROYAL—All but the Crown!

The emily Dickinson inTernaTional socieTy Volume 21, Number 2 November/December 2009 “The Only News I know / Is Bulletins all Day / From Immortality.” emily dickinson in20ternation0al so9ciety general meeting EMILY DICKINSON: ROYA L — all but the Crown! Queen Without a Crown July –August , , Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada eDis 2009 annual meeTing Eleanor Heginbotham with Beefeater Guards Emily with Beefeater Guards Suzanne Juhasz, Jonnie Guerra, and Cris Miller with Beefeater Guards Cindy MacKenzie and Emily Special Tea Cake Paul Crumbley, EDIS president and Cindy MacKenzie, organizer of the 2009 Annual Meeting Georgie Strickland, former editor of the Bulletin Bill and Nancy Pridgen, EDIS members George Gleason, EDIS member and Jane Wald, executive director of the Emily Dickinson Museum Jane Eberwein, Gudrun Grabher, Vivian Pollak, Martha Ackmann and Ann Romberger at banquet Group in front of the Provincial Government House and Eleanor Heginbotham at banquet Cover Photo Courtesy of Emily Seelbinder Photos Courtesy of Eleanor Heginbotham and Georgie Strickland I n Th I s Is s u e Page 3 Page 12 Page 33 F e a T u r e s r e v I e w s 3 Queen Without a Crown: EDIS 2009 19 New Publications Annual Meeting By Barbara Kelly, Book Review Editor By Douglas Evans 24 Review of Jed Deppman, Trying to Think with Emily Dickinson 6 Playing Emily or “the welfare of my shoes” Reviewed by Marianne Noble By Barbara Dana 25 Review of Elizabeth Oakes, 9 Teaching and Learning at the The Luminescence of All Things Emily Emily Dickinson Museum Reviewed by Janet -

Courtroom Drama with Chinese Characteristics: a Comparative Approach to Legal Process in Chinese Cinema

Courtroom Drama With Chinese Characteristics: A Comparative Approach to Legal Process in Chinese Cinema Stephen McIntyre* While previous “law and film” scholarship has concentrated mainly on Hollywood films, this article examines legal themes in Chinese cinema. It argues that Chinese films do not simply mimic Western conventions when portraying the courtroom, but draw upon a centuries-old, indigenous tradition of “court case” (gong’an) melodrama. Like Hollywood cinema, gong’an drama seizes upon the dramatic and narrative potential of legal trials. Yet, while Hollywood trial films turn viewers into jurors, pushing them back and forth between the competing stories that emerge from the adversarial process, gong’an drama eschews any recognition of opposing narratives, instead centering on the punishment of decidedly guilty criminals. The moral clarity and punitive sense of justice that characterize gong’an drama are manifest in China’s modern-day legal system and in Chinese cinema. An analysis of Tokyo Trial, a 2006 Chinese film about the post-World War II war crimes trial in Japan, demonstrates the lasting influence of gong’an drama. Although Tokyo Trial resembles Hollywood courtroom drama in many respects, it remains faithful to the gong’an model. This highlights the robustness of China’s native gong’an tradition and the attitudes underlying it. * J.D., Duke University School of Law; M.A., East Asian Studies, Duke University; B.A., Chinese, Brigham Young University. I thank Professor Guo Juin Hong for his valuable comments and encouragement. I also thank those who attended and participated in the 2011 Kentucky Foreign Language Conference at the University of Kentucky, at which I presented an earlier version of this article. -

Proquest Dissertations

JUSTICE AT 24 FRAMES PER SECOND: LAW AND SPECTACLE IN THE REVENGE FILM By Robert John Tougas B.A. (Hons.), LL.B., B.A. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Film Studies Carleton University OTTAWA, Ontario (May 15,2008) 2008, Robert John Tougas Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43498-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43498-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

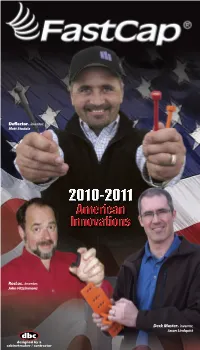

Fastcap 21-30

DeflectorTM inventor, Matt Stodola RocLocTM inventor, John Fitzsimmons Deck MasterTM inventor, Jason Lindquist dbc designed by a cabinetmaker / contractor PRO Tools VLRQDO RIHV JUDG SU H Artisan Accents TM JUHDWSULFH & Mortise Tool Turn of the century craftsmanship with the tap of a hammer. Available in three sizes: 5/16”, 3/8” and 2”, create a beautiful ebony pinned look with the Mortise ToolTM and Artisan AccentsTM. Combining the two allows you to create the look of Greene & Greene furniture in a fraction of the time. Everyone will think you spent hours using ebony pins, flush cut saws and meticulously sanding. “Stop The StruggleTM” 1. Identify where the pin needs to go and tap with the Mortise ToolTM to make the Get the “Greene & Greene” look Accent divots. 2. Install a trim screw, if using one (it is not necessary; the Accents can simply be decorative). 3. Align the Artisan AccentTM in the divots, tap with a hammer until the edge of the Artisan AccentTM is flush with the edge of the wood and you are done! Note: Apply a dab of 2P-10TM Jël under the Artisan AccentTM for a permanent hold. Fast & simple! The 2” Artisan Chisel on an air hammer leaves a perfect outline for the Accents. The Artisan Accent tools are intended for use in real wood Great for... applications. Not recommended • Furniture • Beams for use on man-made material. • Cabinets • Rafters • Trim • Decks • and more! A Pocket Chisel creates square corners for the accent 2” 5 ⁄16” A small dab of 2P-10 Jël in the corners locks the Accent in place 3 ⁄8” Patent Pending Description Part Number USD Artisan Accents (50 pc) 5/16” ARTISAN ACCENT 5/16 $5.00 Mortise Tool (5/16”) MORTISE TOOL 5/16 $20.00 Artisan Accents (50 pc) 3/8” ARTISAN ACCENT 3/8 $5.00 Mortise Tool (3/8”) MORTISE TOOL 3/8 $20.00 Inventor, Artisan Accents (10 pc) 2” ARTISAN ACCENT 2 $9.99 Jeff Marholin Artisan Chisel 2” ARTISAN CHISEL 2 $59.99 A fi nished professional look dbc designed by a cabinetmaker www.fastcap.com 21 PRO Tools TM *Four corners shown Screw the Ass. -

Civil Trials: a Film Illusion?

Fordham Law Review Volume 85 Issue 5 Article 26 2017 Civil Trials: A Film Illusion? Taunya L. Banks University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Civil Law Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Taunya L. Banks, Civil Trials: A Film Illusion?, 85 Fordham L. Rev. 1969 (2017). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol85/iss5/26 This Colloquium is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CIVIL TRIALS: A FILM ILLUSION? Taunya Lovell Banks* INTRODUCTION The right to trial in civil cases is enshrined in the U.S. Constitution1 and most state constitutions.2 The lack of a provision for civil jury trials in the original draft of the Constitution “almost derailed the entire project.”3 According to the French social scientist Alexis de Tocqueville, the American jury system is so deeply engrained in American culture “that it turns up in and structures even the sheerest forms of play.”4 De Tocqueville’s observation, made in the early nineteenth century, is still true today. Most people, laypersons and legal professionals alike, consider trials an essential component of American democracy. In fact, “the adversarial structure is one of the most salient cultural features of the American legal system. -

2012 Kill the Rapist Movie Free Download in Hindi Mp4 Free

2012 Kill The Rapist Movie Free Download In Hindi Mp4 Free 2012 Kill The Rapist Movie Free Download In Hindi Mp4 Free 1 / 4 2 / 4 It's no longer a man's world " -tagline for Ms. 45 Rape and revenge films . Start your free trial; Film Schools Program Gift MUBI Ways to Watch; Help . Rape/revenge movies generally follow the same three act structure: Act I: A . In some cases, the woman is killed at the end of the first act, and the . 7 December 2012.. 5 Sep 2018 . India changed its rape laws after the 2012 Delhi gang rape in which a female . Australian man guilty of child sex offences in India set free.. 26 May 2014 - 143 min - Uploaded by NewIndiaDigitalHaunted Hindi movies 2016 Full Movie HD Hindi Movies Haunted -- 3D is part of 2011 .. 12 Sep 2016 . A Muslim woman who was gang raped in India has said her attackers asked her whether she ate beef in what some suspect was another crime.. Movie Title/Year and Film/Scene Description . American Reunion (2012) . However, Jules was almost immediately killed and decapitated by zombies. She was rape-attacked (mostly off-screen) by an invisible demonic figure. existential angst and frequent free sex, was highlighted in this randomly-episodic film.. 10 Apr 2018 . Kill The Rapist (2013) Hindi Full Movie Watch Online . Watch Download. Kill The . Mp4 Hd Befikre Download Free Mp4 Hd . Kill The Rapist . Download Kill Bill: Vol. Hate Story (2012) Hindi Full Movie. Watch Hate story 4.. 1 Jun 2018 . Find Where Full Movies Is .