Species and Community Profiles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ovarian Development of the Mud Crab Scylla Paramamosain in a Tropical Mangrove Swamps, Thailand

Available Online JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH Publications J. Sci. Res. 2 (2), 380-389 (2010) www.banglajol.info/index.php/JSR Ovarian Development of the Mud Crab Scylla paramamosain in a Tropical Mangrove Swamps, Thailand M. S. Islam1, K. Kodama2, and H. Kurokura3 1Department of Aquaculture and Fisheries, Jessore Science and Technology University, Jessore- 7407, Bangladesh 2Marine Science Institute, The University of Texas at Austin, Channel View Drive, Port Aransas, Texas 78373, USA 3Laboratory of Global Fisheries Science, Department of Global Agricultural Sciences, The University of Tokyo, Bunkyo, Tokyo 113-8657, Japan Received 15 October 2009, accepted in revised form 21 March 2010 Abstract The present study describes the ovarian development stages of the mud crab, Scylla paramamosain from Pak Phanang mangrove swamps, Thailand. Samples were taken from local fishermen between June 2006 and December 2007. Ovarian development was determined based on both morphological appearance and histological observation. Ovarian development was classified into five stages: proliferation (stage I), previtellogenesis (II), primary vitellogenesis (III), secondary vitellogenesis (IV) and tertiary vitellogenesis (V). The formation of vacuolated globules is the initiation of primary vitellogenesis and primary growth. The follicle cells were found around the periphery of the lobes, among the groups of oogonia and oocytes. The follicle cells were hardly visible at the secondary and tertiary vitellogenesis stages. Yolk granules occurred in the primary vitellogenesis stage and are first initiated in the inner part of the oocytes, then gradually concentrated to the periphery of the cytoplasm. The study revealed that the initiation of vitellogenesis could be identified by external observation of the ovary but could not indicate precisely. -

Sediment Transport in the San Francisco Bay Coastal System: an Overview

Marine Geology 345 (2013) 3–17 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/margeo Sediment transport in the San Francisco Bay Coastal System: An overview Patrick L. Barnard a,⁎, David H. Schoellhamer b,c, Bruce E. Jaffe a, Lester J. McKee d a U.S. Geological Survey, Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center, Santa Cruz, CA, USA b U.S. Geological Survey, California Water Science Center, Sacramento, CA, USA c University of California, Davis, USA d San Francisco Estuary Institute, Richmond, CA, USA article info abstract Article history: The papers in this special issue feature state-of-the-art approaches to understanding the physical processes Received 29 March 2012 related to sediment transport and geomorphology of complex coastal–estuarine systems. Here we focus on Received in revised form 9 April 2013 the San Francisco Bay Coastal System, extending from the lower San Joaquin–Sacramento Delta, through the Accepted 13 April 2013 Bay, and along the adjacent outer Pacific Coast. San Francisco Bay is an urbanized estuary that is impacted by Available online 20 April 2013 numerous anthropogenic activities common to many large estuaries, including a mining legacy, channel dredging, aggregate mining, reservoirs, freshwater diversion, watershed modifications, urban run-off, ship traffic, exotic Keywords: sediment transport species introductions, land reclamation, and wetland restoration. The Golden Gate strait is the sole inlet 9 3 estuaries connecting the Bay to the Pacific Ocean, and serves as the conduit for a tidal flow of ~8 × 10 m /day, in addition circulation to the transport of mud, sand, biogenic material, nutrients, and pollutants. -

Bothin Marsh 46

EMERGENT ECOLOGIES OF THE BAY EDGE ADAPTATION TO CLIMATE CHANGE AND SEA LEVEL RISE CMG Summer Internship 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Research Introduction 2 Approach 2 What’s Out There Regional Map 6 Site Visits ` 9 Salt Marsh Section 11 Plant Community Profiles 13 What’s Changing AUTHORS Impacts of Sea Level Rise 24 Sarah Fitzgerald Marsh Migration Process 26 Jeff Milla Yutong Wu PROJECT TEAM What We Can Do Lauren Bergenholtz Ilia Savin Tactical Matrix 29 Julia Price Site Scale Analysis: Treasure Island 34 Nico Wright Site Scale Analysis: Bothin Marsh 46 This publication financed initiated, guided, and published under the direction of CMG Landscape Architecture. Conclusion Closing Statements 58 Unless specifically referenced all photographs and Acknowledgments 60 graphic work by authors. Bibliography 62 San Francisco, 2019. Cover photo: Pump station fronting Shorebird Marsh. Corte Madera, CA RESEARCH INTRODUCTION BREADTH As human-induced climate change accelerates and impacts regional map coastal ecologies, designers must anticipate fast-changing conditions, while design must adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate change. With this task in mind, this research project investigates the needs of existing plant communities in the San plant communities Francisco Bay, explores how ecological dynamics are changing, of the Bay Edge and ultimately proposes a toolkit of tactics that designers can use to inform site designs. DEPTH landscape tactics matrix two case studies: Treasure Island Bothin Marsh APPROACH Working across scales, we began our research with a broad suggesting design adaptations for Treasure Island and Bothin survey of the Bay’s ecological history and current habitat Marsh. -

Vegetation and Biodiversity Management Plan Pdf

April 2015 VEGETATION AND BIODIVERSITY MANAGEMENT PLAN Marin County Parks Marin County Open Space District VEGETATION AND BIODIVERSITY MANAGEMENT PLAN DRAFT Prepared for: Marin County Parks Marin County Open Space District 3501 Civic Center Drive, Suite 260 San Rafael, CA 94903 (415) 473-6387 [email protected] www.marincountyparks.org Prepared by: May & Associates, Inc. Edited by: Gail Slemmer Alternative formats are available upon request TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents GLOSSARY 1. PROJECT INITIATION ...........................................................................................................1-1 The Need for a Plan..................................................................................................................1-1 Overview of the Marin County Open Space District ..............................................................1-1 The Fundamental Challenge Facing Preserve Managers Today ..........................................1-3 Purposes of the Vegetation and Biodiversity Management Plan .....................................1-5 Existing Guidance ....................................................................................................................1-5 Mission and Operation of the Marin County Open Space District .........................................1-5 Governing and Guidance Documents ...................................................................................1-6 Goals for the Vegetation and Biodiversity Management Program ..................................1-8 Summary of the Planning -

San Francisco Bay Plan

San Francisco Bay Plan San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission In memory of Senator J. Eugene McAteer, a leader in efforts to plan for the conservation of San Francisco Bay and the development of its shoreline. Photo Credits: Michael Bry: Inside front cover, facing Part I, facing Part II Richard Persoff: Facing Part III Rondal Partridge: Facing Part V, Inside back cover Mike Schweizer: Page 34 Port of Oakland: Page 11 Port of San Francisco: Page 68 Commission Staff: Facing Part IV, Page 59 Map Source: Tidal features, salt ponds, and other diked areas, derived from the EcoAtlas Version 1.0bc, 1996, San Francisco Estuary Institute. STATE OF CALIFORNIA GRAY DAVIS, Governor SAN FRANCISCO BAY CONSERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION 50 CALIFORNIA STREET, SUITE 2600 SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA 94111 PHONE: (415) 352-3600 January 2008 To the Citizens of the San Francisco Bay Region and Friends of San Francisco Bay Everywhere: The San Francisco Bay Plan was completed and adopted by the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission in 1968 and submitted to the California Legislature and Governor in January 1969. The Bay Plan was prepared by the Commission over a three-year period pursuant to the McAteer-Petris Act of 1965 which established the Commission as a temporary agency to prepare an enforceable plan to guide the future protection and use of San Francisco Bay and its shoreline. In 1969, the Legislature acted upon the Commission’s recommendations in the Bay Plan and revised the McAteer-Petris Act by designating the Commission as the agency responsible for maintaining and carrying out the provisions of the Act and the Bay Plan for the protection of the Bay and its great natural resources and the development of the Bay and shore- line to their highest potential with a minimum of Bay fill. -

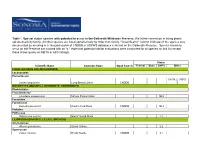

Table *. Special Status Species with Potential to Occur in the Galbreath Wildlands Preserve

Table *. Special status species with potential to occur in the Galbreath Wildlands Preserve. We follow convention in listing plants aphabetically by family. All other species are listed alphabetically by order then family. "Quad Search" column inidicates if the species was documented as occuring in a 16 quad search of CNDDB or USFWS databases centered on the Galbreath Preserve. Species known to occur on the Preserve are marked with an "x." (Note that potential habitat evaluations were conducted for all species on this list except those showing only an MBTA or ABC listings). Status Scientific Name Common Name Quad Search Federal State CNPS Other FUNGI (LICHENS AND MUSHROOMS) Lecanoraeles Parmeliaceae G4 S4.2, USFS: Usnea longissima Long-Beard Lichen CNDDB S BRYOPHYTA (MOSSES, LIVERWORTS, HORNWORTS) Fissidentales Fissidentaceae Fissidens pauperculus Minute Pocket Moss 1B.2 Funariales Funariaceae Entosthodon kochii Koch's Cord Moss CNDDB 1B.3 Pottiales Pottiaceae Didymodon norrisii Norris' Beard Moss 2.2 LILIOPSIDA (GRASSES, LILLIES, ORCHIDS) Alismataceae Alisma gramineum Grass Alisma 2.2 Cyperaceae Carex comosa Bristly Sedge CNDDB 2.1 Carex saliniformis Deceiving Sedge CNDDB 1B.2 Lilaceae Allium peninsulare var. franciscanum Franciscan Onion CNDDB 1B.2 Calochortus raichei The Cedars Fairy-Lantern CNDDB 1B.2 Erythronium revolutum Coast Fawn Lily CNDDB 2.2 Fritillaria roderickii Roderick's Fritillary CNDDB E 1B.1 Orchidaceae Piperia candida White-Flowered Rein Orchid CNDDB 1B.2 Poaceae Dichanthelium lanuginosum var. thermale Geysers Dichanthelium E 1B.1 Glyceria grandis American Manna Grass 2.3 Pleuropogon hooverianus North Coast Semaphore Grass CNDDB T 1B.1 Potamogetonaceae Potamogeton epihydrus ssp. nuttallii Nuttall's Ribbon-Leaved Pondweed 2.2 LILIOPSIDA (GRASSES, LILLIES, ORCHIDS) Asteraceae Hemizonia congesta ssp. -

(Oncorhynchus Mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California

Historical Distribution and Current Status of Steelhead/Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in Streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California Robert A. Leidy, Environmental Protection Agency, San Francisco, CA Gordon S. Becker, Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA Brett N. Harvey, John Muir Institute of the Environment, University of California, Davis, CA This report should be cited as: Leidy, R.A., G.S. Becker, B.N. Harvey. 2005. Historical distribution and current status of steelhead/rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA. Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration TABLE OF CONTENTS Forward p. 3 Introduction p. 5 Methods p. 7 Determining Historical Distribution and Current Status; Information Presented in the Report; Table Headings and Terms Defined; Mapping Methods Contra Costa County p. 13 Marsh Creek Watershed; Mt. Diablo Creek Watershed; Walnut Creek Watershed; Rodeo Creek Watershed; Refugio Creek Watershed; Pinole Creek Watershed; Garrity Creek Watershed; San Pablo Creek Watershed; Wildcat Creek Watershed; Cerrito Creek Watershed Contra Costa County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. 39 Alameda County p. 45 Codornices Creek Watershed; Strawberry Creek Watershed; Temescal Creek Watershed; Glen Echo Creek Watershed; Sausal Creek Watershed; Peralta Creek Watershed; Lion Creek Watershed; Arroyo Viejo Watershed; San Leandro Creek Watershed; San Lorenzo Creek Watershed; Alameda Creek Watershed; Laguna Creek (Arroyo de la Laguna) Watershed Alameda County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. 91 Santa Clara County p. 97 Coyote Creek Watershed; Guadalupe River Watershed; San Tomas Aquino Creek/Saratoga Creek Watershed; Calabazas Creek Watershed; Stevens Creek Watershed; Permanente Creek Watershed; Adobe Creek Watershed; Matadero Creek/Barron Creek Watershed Santa Clara County Maps: Historical Status, Current Status p. -

Botanical Priority Guidebook

Botanical Priority Protection Areas Alameda and Contra Costa Counties the East Bay Regional Park District. However, certain BPPAs include Hills have been from residential development. public parcels or properties with other conservation status. These are cases where land has been conserved since the creation of these boundaries or where potential management decisions have the poten- Following this initial mapping effort, the East Bay Chap- \ ntroduction tial to negatively affect an area’s botanical resources. Additionally, ter’s Conservation Committee began to utilize the con- each acre within these BPPAs represents a potential area of high pri- cept in draft form in key local planning efforts. Lech ority. Both urban and natural settings are included within these Naumovich, the chapter’s Conservation Analyst staff The lands that comprise the East Bay Chapter are located at the convergence boundaries, therefore, they are intended to be considered as areas person, showcased the map set in forums such as the of the San Francisco Bay, the North and South Coast Ranges, the Sacra- warranting further scrutiny due to the abundance of nearby sensitive BAOSC’s Upland Habitat Goals Project and the Green mento-San Joaquin Delta, and the San Joaquin Valley. The East Bay Chapter botanical resources supported by high quality habitat within each E A S T B A Y Vision Group (in association with Greenbelt Alliance); area supports a unique congregation of ecological conditions and native BPPA. Although a parcel, available for preservation through fee title C N P S East Bay Regional Park District’s Master Plan Process; plants. Based on historic botanical collections, the pressures from growth- purchase or conservation easement, may be located within the and local municipalities. -

A Revision of the Marsh Wrens of California. 1

308 Swarth, Marsh Wrens of California. \ia\y October 16. White-throated Sparrow, Ruby-crowned Kinglet. 17. Cowbird, Myrtle Warbler. 18. Bewick's Wren. 20. Vesper Sparrow. 21. Swamp Sparrow. 24. Pipit. 2ti. Wilson's Snipe. 28. Rusty Blackbird. 31. Slate-colored Junco. November 2. Purple Grackle. 4. Purple Finch. 10. Mallard. 15. Fox Sparrow. 21. Pine Siskin. 23. Short-eared Owl. A REVISION OF THE MARSH WRENS OF CALIFORNIA. 1 BY HARRY S. SWARTH. An extensive series of marsh wrens from the delta region east of San Francisco Bay has been accumulated in the California Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, chiefly through the personal efforts of Misses Annie M. Alexander and Louise Kellogg. The appear- ance of these birds contrasts so strongly with specimens avail- able from other parts of California that it has seemed desirable to make a careful study of their systematic status. With this object in view, as many specimens as possible have been assembled illustrative of the Long-billed Marsh Wren (Tclmatodytcs palustris) upon the Pacific Coast, especially in ( alifornia. Although each of the several collections examined or appealed to contained but a meager representation of the species, still, by assembling material 1 Contribution from the University of California Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. Vol. VWIVl Swarth, Marsh 1917 J Wrens of California, 309 from many sources, and for the use of which specific acknowledg- ment is made beyond, a total of 2)59 skins became available. This series, while still leaving gaps to be filled before any precise plotting of breeding ranges can be made, is more than any previous student Points from which specimens were ex- amined: D Telmatodyles p. -

Classification of the Vegetation Alliances and Associations of Sonoma County, California

Classification of the Vegetation Alliances and Associations of Sonoma County, California Volume 1 of 2 – Introduction, Methods, and Results Prepared by: California Department of Fish and Wildlife Vegetation Classification and Mapping Program California Native Plant Society Vegetation Program For: The Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District The Sonoma County Water Agency Authors: Anne Klein, Todd Keeler-Wolf, and Julie Evens December 2015 ABSTRACT This report describes 118 alliances and 212 associations that are found in Sonoma County, California, comprising the most comprehensive local vegetation classification to date. The vegetation types were defined using a standardized classification approach consistent with the Survey of California Vegetation (SCV) and the United States National Vegetation Classification (USNVC) system. This floristic classification is the basis for an integrated, countywide vegetation map that the Sonoma County Vegetation Mapping and Lidar Program expects to complete in 2017. Ecologists with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the California Native Plant Society analyzed species data from 1149 field surveys collected in Sonoma County between 2001 and 2014. The data include 851 surveys collected in 2013 and 2014 through funding provided specifically for this classification effort. An additional 283 surveys that were conducted in adjacent counties are included in the analysis to provide a broader, regional understanding. A total of 34 tree-overstory, 28 shrubland, and 56 herbaceous alliances are described, with 69 tree-overstory, 51 shrubland, and 92 herbaceous associations. This report is divided into two volumes. Volume 1 (this volume) is composed of the project introduction, methods, and results. It includes a floristic key to all vegetation types, a table showing the full local classification nested within the USNVC hierarchy, and a crosswalk showing the relationship between this and other classification systems. -

East Contra Costa County Habitat Conservation Plan – Natural Community Conservation Plan

Agenda Item #7a DRAFT EAST CONTRA COSTA COUNTY HABITAT CONSERVATION PLAN – NATURAL COMMUNITY CONSERVATION PLAN ASSESSMENT OF PLAN EFFECTS ON CEQA SPECIES Prepared for: East Contra Costa County Habitat Conservancy Prepared by: H. T. Harvey & Associates 15 October 2014 983 University Avenue, Building D Los Gatos, CA 95032 Ph: 408.458.3200 F: 408.458.3210 Agenda Item #7a EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The East Contra Costa County Habitat Conservation Plan/Natural Community Conservation Plan (HCP/NCCP or Plan) provides a net benefit to 25 species covered by the endangered species permits issued to participating local agencies. However, projects covered by the Plan must also comply with the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) and evaluate project effects on all special-status species. The Plan satisfies the requirements of CEQA for the 25 species covered by the permits. This report provides an assessment of the effects of the Plan on 59 special-status species that were not covered by the Plan (“CEQA species”), 41 plant and 18 animal species. The purpose of the assessment was to provide a programmatic, cumulative CEQA effects analysis for CEQA species taking into account impacts of all covered activities, including all adverse and beneficial effects of covered development activities and conservation measures. The cumulative effects of the Plan on each species were determined to be beneficial, neutral, adverse but less-than-significant, or potentially significant by considering the number of known populations and extent of suitable habitat that could be adversely affected within areas of anticipated development as well as those that would benefit from being in areas that may be preserved, enhanced, and managed for covered species and communities by the Plan. -

A Cultural and Natural History of the San Pablo Creek Watershed

A Cultural and Natural History of the San Pablo Creek Watershed by Lisa Owens-Viani Prepared by The Watershed Project (previously known as the Aquatic Outreach Institute) Note: This booklet focuses on the watershed from the San Pablo Dam and reservoir westward (downstream). For a history of the Orinda area, see Muir Sorrick's The History of Orinda, published by the Orinda Library Board in 1970. Orinda also has an active creek stewardship group, the Friends of Orinda Creeks, which has conducted several watershed outreach efforts in local schools (see www.ci.orinda.ca.us/orindaway.htm). This booklet was written as part of the Aquatic Outreach Institute's efforts to develop stewardship of the mid- to lower watershed. The San Pablo Creek watershed is a wealthy one-rich in history, culture, and natural resources. The early native American inhabitants of the watershed drank from this deep and powerful creek and caught the steelhead that swam in its waters. They ate the tubers and roots of the plants that grew in the fertile soils deposited by the creek, and buried their artifacts, the shells and bones of the creatures they ate, and even their own dead along its banks. Later, European settlers grew fruit, grain, and vegetables in the same rich soils and watered cattle in the creek. Even today, residents of the San Pablo Creek watershed rely on the creek, perhaps unknowingly: its waters quench the thirst and meet the household needs of about 10 percent of the East Bay Municipal Utility District's customers. Some residents rely on the creek in another way, though-as a reminder that something wild and self-sufficient flows through their midst, offering respite from the surrounding urbanized landscape.