Emily Warren Roebling: Graceful Determination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Teacher's Guide for COBBLESTONE the Great Bridge

Teacher’s Guide for COBBLESTONE The Great Bridge March 2010 By Linda M. Andersen, School Counselor at Eastover-Central Elementary School in Fayetteville, North Carolina Goal: to marvel the engineering process, the historical importance, and the personal commitment and dedication required to build the Brooklyn Bridge. *Always have a parent or adult you trust help you research websites. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- “A Bridge to History” by Emily Goodman (Pages 2-3) Pre-reading: What do you know about the Brooklyn Bridge? What would you like to learn? Vocabulary Check: boroughs, span, pedestrians, suspension, drawback, convenient, hectic, whizzing, exhaust, links, and inspires. Comprehension Check: 1. Tell how New York is like five cities in one. 2. Name three or more different types of bridges. 3. Explain the purpose of a bridge. 4. What does the author mean when she says, “It’s a beautiful historic monument that is used by ordinary people every day?” 5. What does the author mean when she says, “It fills a need and inspires at the same time?” Would you agree or disagree and why? Writing Activity: • Pretend you are visiting New York City and you decide to walk across the Brooklyn Bridge. List three things you would hope to see, smell, and hear. • Write a creative statement or a short poem about the bridge. For example, choose two more words that begin with “b” and make a statement such as: Brooklyn Bridge benefits barges. Research/Bulletin Board: • Locate photos of old bridges. Identify the types, if possible. Post articles, pamphlets, and other information about old bridges on a bulletin board during this study. -

Don't Let Me Down Chainsmokers Album Download Don't Let Me Down

don't let me down chainsmokers album download Don't Let Me Down. Purchase and download this album in a wide variety of formats depending on your needs. Buy the album Starting at £1.99. Don't Let Me Down. Copy the following link to share it. You are currently listening to samples. Listen to over 70 million songs with an unlimited streaming plan. Listen to this album and more than 70 million songs with your unlimited streaming plans. 1 month free, then £14,99/ month. The Chainsmokers, Associated Performer, Main Artist, Producer - Daya, Associated Performer, Featured Artist - The Chainsmokers feat. Daya, Associated Performer - Andrew Taggart, Composer, Lyricist - Emily Warren, Composer, Lyricist - Jordan "DJ Swivel" Young, Mixing Engineer - Chris Gehringer, Mastering Engineer - Scott Harris, Composer, Lyricist. (P) 2015 Disruptor Records/Columbia Records. About the album. 1 disc(s) - 1 track(s) Total length: 00:03:28. (P) 2015 Disruptor Records/Columbia Records. Why buy on Qobuz. Stream or download your music. Buy an album or an individual track. Or listen to our entire catalogue with our high-quality unlimited streaming subscriptions. Zero DRM. The downloaded files belong to you, without any usage limit. You can download them as many times as you like. Choose the format best suited for you. Download your purchases in a wide variety of formats (FLAC, ALAC, WAV, AIFF. ) depending on your needs. Listen to your purchases on our apps. Download the Qobuz apps for smartphones, tablets and computers, and listen to your purchases wherever you go. Don't Let Me Down (Remixes) Purchase and download this album in a wide variety of formats depending on your needs. -

ENERGY MASTERMIX – Playlists Vom 07.09.2018 HELMO

ENERGY MASTERMIX – Playlists vom 07.09.2018 HELMO 1. TIESTO FEAT. POST MALONE JACKIE CHAN 2. JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE CAN'T STOP THE FEELING! (MASTERMIX) 3. WILLY WILLIAM LA LA LA 4. LOST FREQUENCIES & JAMES BLUNT MELODY (MASTERMIX) 5. JAX JONES FEAT. MABEL & RICH THE KID RING RING 6. USHER YEAH (MASTERMIX) 7. ALESSO REMEDY (MASTERMIX) 8. SIGALA FEAT. SEAN PAUL FEELS LIKE HOME 9. DJ SNAKE FEAT. JUSTIN BIEBER LET ME LOVE YOU (MASTERMIX) 10. MARTIN GARRIX HIGH ON LIFE 11. KYGO & IMAGINE DRAGONS BORN TO BE YOURS 12. MARSHMELLO & ANNE-MARIE FRIENDS (MASTERMIX) 13. DON DIABLO FEAT. ALEX CLARE HEAVEN TO ME 14. MILKY CHANCE STOLEN DANCE 15. LOUD LUXARY FEAT. BRANDO BODY (MASTERMIX) 16. EL PROFESOR BELLA CIAO [HUGEL REMIX] 17. THE CHAINSMOKERS FEAT. EMILY WARREN SIDE EFFECTS 18. GALANTIS NO MONEY (MASTERMIX) 19. ROBIN SCHULZ FEAT. PISO 21 OH CHILD 20. DAVID GUETTA & SIA FLAMES (MASTERMIX) 21. DYNORO IN MY MIND 22. AVICII LAY ME DOWN (MASTERMIX) 23. AXWELL /\ INGROSSO DANCING ALONE 24. CLEAN BANDIT & DEMI LOVATO SOLO 25. ZEDD & ELLEY DUHÉ HAPPY NOW 26. FLO RIDA WHISTLE 27. OFENBACH PARADISE (MASTERMIX) 28. CARDI B, BAD BUNNY & J BALVIN I LIKE IT 29. SAM FELDT FEAT. KIMBERLY ANNE SHOW ME LOVE (EDX REMIX) (MASTERMIX) 30. MARTIN SOLVEIG MY LOVE (MASTERMIX) 31. DAVID GUETTA & ANNE-MARIE DON'T LEAVE ME ALONE (MASTERMIX) 32. CALVIN HARRIS & DUA LIPA ONE KISS 33. MAITRE GIMS & ALVARO SOLER LO MISMO (MASTERMIX) 34. BLACK EYED PEAS I GOTTA FEELING (MASTERMIX) 35. MARTIN GARRIX & KHALID OCEAN [DAVID GUETTA REMIX] 36. DENNIS LLOYD NEVERMIND (MASTERMIX) 37. -

Donald W. Reynolds Visual Arts Center OKLAHOMA CITY MUSEUM of ART Donald W

ANNUAL REPORT a publication of the OKLAHOMA CITY MUSEUM OF ART | FY 2010–2011 Donald W. Reynolds Visual Arts Center OKLAHOMA CITY MUSEUM OF ART Donald W. Reynolds Visual Arts Center Annual Report for the Fiscal Year July 1, 2010, through June 30, 2011 Mission To enrich lives through the visual arts Vision Great art for everyone Purpose To create a cultural legacy in art and education that present and future generations can experience at the Museum and carry with them throughout their lives Contents ANNUAL REPORT 2010–2011 Board of Trustees .................................................................................................................................................................. 7 President & CEO’s Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 8 Acquisitions, Loans & Deaccessions ................................................................................................................................ 10 Exhibitions & Installations ................................................................................................................................................... 16 Film ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 18 Education & Public Programs .......................................................................................................................................... -

Winter Showcase Program

2020 UPPER SCHOOL WINTER SHOWCASE VIRTUAL PREMIERE | DECEMBER 18, 2020 AT 7 P.M. ON-DEMAND STREAMING | BEGINNING ON DECEMBER 19, 2020 2020 UPPER SCHOOL WINTER SHOWCASE DIRECTORS Almut Engelhardt Director of Orchestras Randy Reid Director of Bands Anne Klus Director of Choral Activities Tim Kraack Interim Director of Choral Activities ACADEMY CHORALE AND SUMMIT SINGERS Don’t Start Now..................................................................................... Words and Music by Dua Lipa, Caroline Ailin, Emily Warren and Ian Kirkpatrick arr. Tim Kraack Video was produced and edited by Tim Kraack JAZZ BAND Children of Sanchez.................................................................................................................................. Chuck Mangione arr. Victor Lopez Featuring: Ellie Sandeen, flugel horn; Will Shrestha, tenor saxophone; Bridget Keel, trumpet; Ryan Spangler, trombone; Baasit Mahmood, alto saxophone Video was produced and edited by Randy Reid ACADEMY SYMPHONY Hallelujah................................................................................................................. Words and Music by Leonard Cohen arr. Robert Longfield Adapted by JJ Gisselquist ’18 Video was produced and edited by Brandt Baskerville, Kevin Chen, Aman Rahman, and Lucas Schanno SUMMIT SINGERS Like A Girl............................................................................ Written by Lizzo, Sean Douglas and Warren Oak Felder arr. Tim Kraack Vocal soloists: Anja Trierweiler and Hannah Brass Instrumental soloists: -

Roebling and the Brooklyn Bridge

BOOK SUMMARY She built a monument for all time. Then she was lost in its shadow. Discover the fascinating woman who helped design and construct an American icon, perfect for readers of The Other Einstein. Emily Warren Roebling refuses to live conventionally―she knows who she is and what she wants, and she's determined to make change. But then her husband Wash asks the unthinkable: give up her dreams to make his possible. Emily's fight for women's suffrage is put on hold, and her life transformed when Wash, the Chief Engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge, is injured on the job. Untrained for the task, but under his guidance, she assumes his role, despite stern resistance and overwhelming obstacles. Lines blur as Wash's vision becomes her own, and when he is unable to return to the job, Emily is consumed by it. But as the project takes shape under Emily's direction, she wonders whose legacy she is building―hers, or her husband's. As the monument rises, Emily's marriage, principles, and identity threaten to collapse. When the bridge finally stands finished, will she recognize the woman who built it? Based on the true story of the Brooklyn Bridge, The Engineer's Wife delivers an emotional portrait of a woman transformed by a project of unfathomable scale, which takes her into the bowels of the East River, suffragette riots, the halls of Manhattan's elite, and the heady, freewheeling temptations of P.T. Barnum. It's the story of a husband and wife determined to build something that lasts―even at the risk of losing each other. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

An Excellent A&R

An Excellent A&R Work Methods & Characteristics Titta Nevala BACHELOR’S THESIS November 2019 Degree Programme in Media and Arts Music Production ABSTRACT Tampereen ammattikorkeakoulu Tampere University of Applied Sciences Degree Programme in Media and Arts Music Production TITTA NEVALA: An Excellent A&R - Work Methods & Characteristics Bachelor's thesis 38 pages, appendices 1 page November 2019 The purpose of this thesis was to collect information on A&R work by interviewing five A&R’s from Finland and the United States. An A&R, short for ”artists and repertoire”, is a person responsible for scouting talent and guiding artists in a record company. Their role in the music industry is very significant, yet there is very little general knowledge about their line of work. It has maintained the mys- tique of the music business. Your own taste in music has also most likely been shaped by the tastes of legendary A&R’s. But why do we need them? The music industry has gone through considerable changes and recording and publishing music has become more accessible for everyone. Online data is also easily available, if one wants to find out what is currently trending. All of the interviewees believed that there is a strong psycho- logical side to A&R-work, which is equally as important as the musical side. On top of musical guidance, artists need mentors that understands their highs and lows and can guide them through different parts of their careers. There is no specific way of becoming an A&R, and it is not one of those careers people aim for or dream of since childhood. -

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017 Researched, compiled, and calculated by Lance Mangham Contents • Sources • The Top 100 of All-Time • The Top 100 of Each Year (2017-1956) • The Top 50 of 1955 • The Top 40 of 1954 • The Top 20 of Each Year (1953-1930) • The Top 10 of Each Year (1929-1900) SOURCES FOR YEARLY RANKINGS iHeart Radio Top 50 2018 AT 40 (Vince revision) 1989-1970 Billboard AC 2018 Record World/Music Vendor Billboard Adult Pop Songs 2018 (Barry Kowal) 1981-1955 AT 40 (Barry Kowal) 2018-2009 WABC 1981-1961 Hits 1 2018-2017 Randy Price (Billboard/Cashbox) 1979-1970 Billboard Pop Songs 2018-2008 Ranking the 70s 1979-1970 Billboard Radio Songs 2018-2006 Record World 1979-1970 Mediabase Hot AC 2018-2006 Billboard Top 40 (Barry Kowal) 1969-1955 Mediabase AC 2018-2006 Ranking the 60s 1969-1960 Pop Radio Top 20 HAC 2018-2005 Great American Songbook 1969-1968, Mediabase Top 40 2018-2000 1961-1940 American Top 40 2018-1998 The Elvis Era 1963-1956 Rock On The Net 2018-1980 Gilbert & Theroux 1963-1956 Pop Radio Top 20 2018-1941 Hit Parade 1955-1954 Mediabase Powerplay 2017-2016 Billboard Disc Jockey 1953-1950, Apple Top Selling Songs 2017-2016 1948-1947 Mediabase Big Picture 2017-2015 Billboard Jukebox 1953-1949 Radio & Records (Barry Kowal) 2008-1974 Billboard Sales 1953-1946 TSort 2008-1900 Cashbox (Barry Kowal) 1953-1945 Radio & Records CHR/T40/Pop 2007-2001, Hit Parade (Barry Kowal) 1953-1935 1995-1974 Billboard Disc Jockey (BK) 1949, Radio & Records Hot AC 2005-1996 1946-1945 Radio & Records AC 2005-1996 Billboard Jukebox -

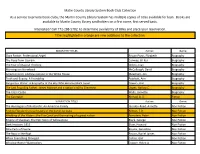

As a Service to Private Book Clubs, the Martin County Library System Has Multiple Copies of Titles Available for Loan

Matin County Library System Book Club Collection As a service to private book clubs, the Martin County Library System has multiple copies of titles available for loan. Books are available to Martin County library cardholders on a first come, first served basis. Interested? Call 772-288-5702 to determine availability of titles and place your reservation. Titles highlighted in orange are new additions to the collection. BIOGRAPHY TITLES Author: Genre: Clara Barton: Professional Angel Brown Pryor, Elizabeth Biography The Road from Coorain Conway, Jill Ker Biography The Year of Magical Thinking Didion, Joan Biography Mornings on Horseback McCullough, David Biography American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House Meacham, Jon Biography Truth and Beauty: A Friendship Patchett, Ann Biography Dangerous Water: A Biography of the Boy Who Became Mark Twain Powers, Ron Biography The Last Founding Father: James Monroe and a nation's call to Greatness Unger, Harlow C. Biography The Glass Castle Walls, Jannette Biography The Caretaker Ahmad, A. X. Fiction NONFICTION TITLES Author: Genre: The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family Gordon-Reed, Annette Non Fiction Finding Florida: the true history of the Sunshine State Allman, T.D. Non Fiction Wedding of the Waters: the Erie Canal and the making of a great nation Bernstein, Peter Non Fiction Empire of Shadows: The Epic Story of Yellowstone Black, George Non Fiction Dark Invasion: 1915 Blum, Howard Non Fiction Nine Parts of Desire Brooks, Geraldine Non Fiction The Boys in the Boat Brown, Daniel James Non Fiction When Everything Changed Collins, Gail Non Fiction Winslow Homer Watercolors Cooper, Helen A Non Fiction Brother, I'm Dying Danticat, Edwidge Non Fiction Duff, James H. -

Legal Use Requires Purchase

INTERMEDIATE STRING ORCHESTRA Grade 2½ A Dua Lipa Duo Featuring Break My Heart and Don’t Start Now Arranged by Michael Story INSTRUMENTATION 1 Full Score 8 Violin I 8 Violin II 5 Violin III (Viola &) 5 Viola 5 Cello 5 String Bass 1 Piano Accompaniment (Optional) 2 Percussion (Tambourine, Shaker/ Cowbell) 1 Drumset NOTES TO THE CONDUCTOR This arrangement is completely playable by strings alone, but there are optional parts provided for piano, drumset, and percussion. The drumset part could also be performed by two percussionists—one on snare, hi-hat cymbals, and tom-tom, and the other on bass drum. If two players are used, the bass drummer should also play on the rim in the sections at measures 21, 52, and 68. “Break My Heart” is set at the moderate tempo of =114. Strive to maintain the medium tempo, as there may be a tendency to rush,q especially the 16th-note patterns. Rhythmic clarity and ensemble precision with the staccato notes are important for a successful performance. In “Don’t Start Now,” the divided notes in the 1st violin starting in measure 75 are meant to be performed as double stops. However, you may wish to treat these as divisi instead. I hope you and your orchestra enjoy A Dua Lipa Duo! NOTE FROM THE EDITOR In orchestral music, there are many editorial markings that are open for interpretation. In an effort to maintain consistency and clarity you may find some of these markings in this piece. In general, markings for fingerings, bowing patterns, and other items will onlyPreview be marked with their initial appearance.