Mohammed Ali Nicholas Sa'id

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lost & Found Children of Abraham in Africa and The

SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International The Lost & Found Children of Abraham In Africa and the American Diaspora The Saga of the Turudbe’ Fulbe’ & Their Historical Continuity Through Identity Construction in the Quest for Self-Determination by Abu Alfa Umar MUHAMMAD SHAREEF bin Farid 0 Copyright/2004- Muhammad Shareef SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International www.sankore.org/www,siiasi.org All rights reserved Cover design and all maps and illustrations done by Muhammad Shareef 1 SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International www.sankore.org/ www.siiasi.org ﺑِ ﺴْ ﻢِ اﻟﻠﱠﻪِ ا ﻟ ﺮﱠ ﺣْ ﻤَ ﻦِ ا ﻟ ﺮّ ﺣِ ﻴ ﻢِ وَﺻَﻠّﻰ اﻟﻠّﻪُ ﻋَﻠَﻲ ﺳَﻴﱢﺪِﻧَﺎ ﻣُ ﺤَ ﻤﱠ ﺪٍ وﻋَﻠَﻰ ﺁ ﻟِ ﻪِ وَ ﺻَ ﺤْ ﺒِ ﻪِ وَ ﺳَ ﻠﱠ ﻢَ ﺗَ ﺴْ ﻠِ ﻴ ﻤ ﺎً The Turudbe’ Fulbe’: the Lost Children of Abraham The Persistence of Historical Continuity Through Identity Construction in the Quest for Self-Determination 1. Abstract 2. Introduction 3. The Origin of the Turudbe’ Fulbe’ 4. Social Stratification of the Turudbe’ Fulbe’ 5. The Turudbe’ and the Diffusion of Islam in Western Bilad’’s-Sudan 6. Uthman Dan Fuduye’ and the Persistence of Turudbe’ Historical Consciousness 7. The Asabiya (Solidarity) of the Turudbe’ and the Philosophy of History 8. The Persistence of Turudbe’ Identity Construct in the Diaspora 9. The ‘Lost and Found’ Turudbe’ Fulbe Children of Abraham: The Ordeal of Slavery and the Promise of Redemption 10. Conclusion 11. Appendix 1 The `Ida`u an-Nusuukh of Abdullahi Dan Fuduye’ 12. Appendix 2 The Kitaab an-Nasab of Abdullahi Dan Fuduye’ 13. -

Nigeria – Complex Emergency JUNE 7, 2021

Fact Sheet #3 Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 Nigeria – Complex Emergency JUNE 7, 2021 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 206 8.7 2.9 308,000 12.8 MILLION MILLION MILLION MILLION Estimated Estimated Number of Estimated Estimated Projected Acutely Population People in Need in Number of IDPs Number of Food-Insecure w of Nigeria Northeast Nigeria in Nigeria Nigerian Refugees Population for 2021 in West Africa Lean Season UN – December 2020 UN – February 2021 UNHCR – February 2021 UNHCR – April 2021 CH – March 2021 Major OAG attacks on population centers in northeastern Nigeria—including Borno State’s Damasak town and Yobe State’s Geidam town—have displaced hundreds of thousands of people since late March. Intercommunal violence and OCG activity continue to drive displacement and exacerbate needs in northwest Nigeria. Approximately 12.8 million people will require emergency food assistance during the June-to-August lean season, representing a significant deterioration of food security in Nigeria compared with 2020. 1 TOTAL U.S. GOVERNMENT HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA $230,973,400 For the Nigeria Response in FY 2021 State/PRM2 $13,500,000 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see detailed chart on page 7 Total $244,473,400 1 USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA) 2 U.S. Department of State Bureau for Population, Refugees, and Migration (State/PRM) 1 KEY DEVELOPMENTS Violence Drives Displacement and Constrains Access in the Northeast Organized armed group (OAG) attacks in Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe states have displaced more than 200,000 people since March and continue to exacerbate humanitarian needs and limit relief efforts, according to the UN. -

Kukawa Local Government Area (LGA)

Nigeria-Borno: Kukawa Local Government Area (LGA) 5 Lariski Ngama . JabullaJmab Suollaumth DSaoyuath Yitiwa 3 Ngarwa Yau Ngalja Foliwa NIGER 1 CHAD Jabullam Yau Karam Kalwa Maiduguri 4 . Kusulluwa Bida'A 3 Foguwa Arege 1 Billara Bongo Diyau Dogon Chiku Mashayi Abadam CAMEROON Kaliliya Duguri Masaram CHAD 3 . 3 Garere Kiriye 1 CHAD Gawaya Banowa 2 LGA . Doro Naira 3 Gariye Ngawe 1 Doro Warrangallam Ward Banowa Alagarno Abara Dugu LGA HQs Bogum Doro Gowon 1 . Mobbar Baga 3 1 Primary Road Duriya Lake Chad Asandi Shiwari Ganganwa Sawari Secondary Road Kukawa River 3 Isaka Shehuri 1 Gudumbali West 3 Kiryari Maigamiri 1 Nyau Magana Gudumbali East Gofdare Barwati Laikbari Alagarno Kauwa Baga Kosorok Kajiduri Gudumbali Cross Kauwa Kalla Maulau KKuurakawa Bashir Yanami Kelesua Kallamare Kanguri 9 Shehuri Wadiri . Bashir Bulama Modu Kukawa 2 Bulama Kaanami 1 Moduri Kafetowa Malamti Bundur Mallam Amsari Buraa KuraDowuturi Gesada Kullomari Karwa Matari Dogoshi Guzamala Buluri Goni Ajiri GuGwaroanrdaamrimandarari CAMEROON Fulairam Bolle 8 Gongi Dabarmasara . 2 Aduwa Ali Kundiriri 1 Kekeno Shettimari Wamiri Goni Moduri Mile Ninety Kangarwa Kura Njino Modu Garwa Kurnawa Yoyo Tamsuwa Kararambe Akrari Gani Ram Guzamala East Ya Shettimari Tunbun Buhari Gezeriya Mintar 7 Ngurno . Badu 2 Nganzai Goni Suwuri Bulamari Lingir 1 Badu Mairari Kumalia Monguno Felo Za'A Bulama Mojuye Mairari Monguno Kingarwa Dungurom Guzamala West Bukar Kannari Mattari Mallamti Kingiri Buzabe Fugu Dallari Duwabai Mbatti Wulari Nomadic Kla Balia Malamti Kabal Balram Kolori Gasarwa -

Elijah Muhammad's Nation of Islam Separatism, Regendering, and A

Africana Islamic Studies THE AFRICANA EXPERIENCE AND CRITICAL LEADERSHIP STUDIES Series Editors: Abul Pitre, PhD North Carolina A&T State University Comfort Okpala, PhD North Carolina A&T State University Through interdisciplinary scholarship, this book series explores the experi- ences of people of African descent in the United States and abroad. This series covers a wide range of areas that include but are not limited to the following: history, political science, education, science, health care, sociol- ogy, cultural studies, religious studies, psychology, hip-hop, anthropology, literature, and leadership studies. With the addition of leadership studies, this series breaks new ground, as there is a dearth of scholarship in leadership studies as it relates to the Africana experience. The critical leadership studies component of this series allows for interdisciplinary, critical leadership dis- course in the Africana experience, offering scholars an outlet to produce new scholarship that is engaging, innovative, and transformative. Scholars across disciplines are invited to submit their manuscripts for review in this timely series, which seeks to provide cutting edge knowledge that can address the societal challenges facing Africana communities. Titles in this Series Survival of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities: Making it Happen Edited by Edward Fort Engaging the Diaspora: Migration and African Families Edited by Pauline Ada Uwakweh, Jerono P. Rotich, and Comfort O. Okpala Africana Islamic Studies Edited by James L. Conyers and Abul Pitre Africana Islamic Studies Edited by James L. Conyers Jr. and Abul Pitre LEXINGTON BOOKS Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Lexington Books An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. -

Stars on Their Shoulders. Blood on Their Hands

STARS ON THEIR SHOULDERS. BLOOD ON THEIR HANDS. WAR CRIMES COMMITTED BY THE NIGERIAN MILITARY Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2015 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2015 Index: AFR 44/1657/2015 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Nigerian troops inspect the former emir's palace that was used by Boko Haram as their headquarters but was burnt down when they fled Bama on March 25, 2015. Nigeria's military has retaken the northeastern town of Bama from Boko Haram, but signs of mass killings carried out by Boko Haram earlier this year remain Approximately 7,500 people have been displaced by the fighting in Bama and surrounding areas. -

Resilience Analysis in Borno State, Nigeria

AnalysIng Resilience for better targeting and action and targeting better Resiliencefor AnalysIng RESILIENCE ANALYSIS ANALYSIS RESILIENCE IN BORNO STATE BORNO IN FAO resilience RESILIENCE INDEX MEASUREMENT AND ANALYSIS II y RIMA II analysis report No. 16 AnalysIng Resilience for better targeting and action FAO resilience analysis report No. 16 RESILIENCE ANALYSIS IN BORNO STATE I g e r i Na Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2019 Required citation: FAO. 2019. Resilience analysis in Borno State, Nigeria. Rome. 44 pp. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. © FAO, 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode/legalcode). Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. -

Cadre Harmonize Result for Identification of Risk Areas and Vulnerable Populations in Fifteen (15) Northern States and the Feder

Cadre Harmonize Result for Identification of Risk Areas and Vulnerable Populations in Fifteen (15) Northern States and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) of Nigeria Results of the Analysis of Current (October to December, 2020) and Projected Prepared: 05/11/2020 Nigeria (June to August 2021) The main results for zones/LGAs affected by food The Cadre Harmonize (CH) is the framework for the consensual analysis of acute food and and nutrition insecurity in the 15 states of nutrition insecurity in the Sahel and West Africa region. The CH process is coordinated by CILSS Adamawa, Bauchi, Benue, Borno, Gombe, and jointly managed by ECOWAS and UEMOA within the Sahel and West African sub-region. Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Niger, The analysis considered the standard food and nutrition security outcome indicators, namely, food Plateau, Taraba, Sokoto, Yobe and the FCT consumption, livelihood change, nutritional status, and mortality. The impact of several indicated that 146 Zones/LGAs in the fifteen (15) contributing factors such as hazards and vulnerabilities, food availability, food access, food states and the FCT are classified under the utilization including water and stability was assessed on these outcomes variables. The results minimal phase of food and nutrition insecurity in indicate that about 10 million (9.8 %) people of the analysed population require urgent assistance the current period. During the projected period, 58 in the current period (October to December 2020). During the projected period (June to August LGAs in Adamawa, Borno, Yobe, and Sokoto 2021), these figures are expected to increase to 13.8 (12.9%) million people unless resilience States will be either in the crisis or emergency driven interventions and humanitarian assistance in conflict affected LGAs is sustained. -

Jobdescription

JJOOBB DDEESSCCRRIIPPTTIIOONN Preliminary job information Job Title HEALTH & NUTRITION PROJECT MANAGER Country & Base of posting NIGERIA – MONGUNO BASE Reports to MONGUNO BASE FIELD COORDINATOR Creation / Replacement CREATION Duration of Mission 6 MONTHS MINIMUM General information on the mission Context Première Urgence Internationale (PUI) is a Humanitarian, non-governmental, non-profit, non-political and non-religious international aid organization. Our teams are committed to supporting civilian victims of marginalization and exclusion, or hit by natural disasters, wars and economic collapses, by addressing their fundamental needs. Our aim is to provide emergency relief to uprooted people in order to help them recover their dignity and regain self-sufficiency. The association leads on average 190 projects per year in the following sectors of intervention: food security, health, nutrition, construction and rehabilitation of infrastructures, water, sanitation, hygiene and economic recovery. PUI is providing assistance to around 7 million people in more than 21 countries – in Africa, Asia, Middle East, and Europe. Following the escalation of the Chad Lake conflict in Nigeria (North East of the Country), PUI has decided to also respond to this crisis from Nigeria. (since the organization already assists the Nigerian refugees in Cameroon) General Context : With the biggest population in Africa, (between 178.000.000 and 200.000.000 habitants), Nigeria is ranked as the first economy in Africa mainly thanks to oil and petroleum products as well as mineral resources (gold, iron, diamonds, copper etc…). Despite a strong economy (although the past few years witnessed a significant weakening of economic growth), Nigeria suffers from huge socio-economic inequalities, and from high incidence of corruption, at every level. -

Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC)

FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) BORNO STATE DIRECTORY OF POLLING UNITS Revised January 2015 DISCLAIMER The contents of this Directory should not be referred to as a legal or administrative document for the purpose of administrative boundary or political claims. Any error of omission or inclusion found should be brought to the attention of the Independent National Electoral Commission. INEC Nigeria Directory of Polling Units Revised January 2015 Page i Table of Contents Pages Disclaimer.............................................................................. i Table of Contents ……………………………………………… ii Foreword................................................................................ iv Acknowledgement.................................................................. v Summary of Polling Units....................................................... 1 LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREAS Abadam …………………………………………………... 2-5 Askira/Uba …………………………………………..…… 6-15 Bama …………………………………………..…………. 16-28 Bayo …………………………………………..………….. 29-32 Biu …………………………………………..……………. 33-42 Chibok ……………………………………………………. 43-47 Damboa ………………………………………………….. 48-53 Dikwa …………………………………………………….. 54-58 Gubio ……………………………………………………... 59-64 Guzamala ………………………………………………… 65-69 Gwoza ……………………………………………………. 70-81 Hawul …………………………………………………..… 82-88 Jere ……………………………………………………….. 89-98 Kaga ……………………………………………………… 99-104 Kala/Balge ………………………………………..……… 105-109 Konduga ………………………………………..………… 110-118 Kukawa ………………………………………..……….… 119-123 Kwaya/Kusar …………………………………………..… -

World Bank Documents

PROCUREMENT PLAN (Textual Part) Project information: Country: Nigeria Public Disclosure Authorized Project Name: Multi-Sectoral Crisis Recovery Project for North East Nigeria (MCRP) P- Number: P157891 Project Implementation Agency: MCRP PCU (Federal and States) Date of the Procurement Plan: Updated -December 22, 2017. Period covered by this Procurement Plan: From 01/12/2018 – 30/06/2019. Public Disclosure Authorized Preamble In accordance with paragraph 5.9 of the “World Bank Procurement Regulations for IPF Borrowers” (July 2016) (“Procurement Regulations”) the Bank’s Systematic Tracking and Exchanges in Procurement (STEP) system will be used to prepare, clear and update Procurement Plans and conduct all procurement transactions for the Project. This textual part along with the Procurement Plan tables in STEP constitute the Procurement Plan for the Project. The following conditions apply to all procurement activities in the Procurement Plan. The other elements of the Procurement Plan as required under paragraph 4.4 of the Procurement Regulations are set forth in STEP. Public Disclosure Authorized The Bank’s Standard Procurement Documents: shall be used for all contracts subject to international competitive procurement and those contracts as specified in the Procurement Plan tables in STEP. National Procurement Arrangements: In accordance with paragraph 5.3 of the Procurement Regulations, when approaching the national market (as specified in the Procurement Plan tables in STEP), the country’s own procurement procedures may be used. When the Borrower uses its own national open competitive procurement arrangements as set forth in the FGN Public Procurement Act 2007; such arrangements shall be subject to paragraph 5.4 of the Procurement Regulations. -

Nigeria Where Boko Haram

Country Policy and Information Note Nigeria: Islamist extremist groups in North East Nigeria Version 3.0 July 2021 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into 2 parts: (1) an assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note - that is information in the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw - by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: • a person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • that the general humanitarian situation is so severe that there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk of serious harm because conditions amount to inhuman or degrading treatment as within paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) • that the security situation is such that there are substantial grounds for believing there is a real risk of serious harm because there exists a serious and individual threat to a civilian’s life or person by reason of indiscriminate violence in a situation of international or internal armed conflict as within paragraphs 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules • a person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • a person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • a claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • if a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

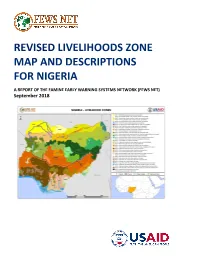

Nigeria Livelihood Zone Map and Descriptions 2018

REVISED LIVELIHOODS ZONE MAP AND DESCRIPTIONS FOR NIGERIA A REPORT OF THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) September 2018 NIGERIA Livelihood Zone Map and Descriptions September 2018 Acknowledgements and Disclaimer This report reflects the results of the Livelihood Zoning Plus exercise conducted in Nigeria in July to August 2018 by FEWS NET and partners: the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (FMA&RD) and the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), the United Nations World Food Program, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, and various foundation and non-government organizations working to improve the lives and livelihoods of the people of Nigeria. The Livelihood Zoning Plus workshops whose results are the subject of this report were led by Julius Holt, consultant to FEWS NET, Brian Svesve, FEWS NET Regional Food Security Specialist – Livelihoods and Stephen Browne, FEWS NET Livelihoods Advisor, with technical support from Dr. Erin Fletcher, consultant to FEWS NET. The workshops were hosted and guided by Isa Mainu, FEWS NET National Technical Manager for Nigeria, and Atiku Mohammed Yola, FEWS NET Food Security and Nutrition Specialist. This report was produced by Julius Holt from the Food Economy Group and consultant to FEWS NET, with the support of Nora Lecumberri, FEWS NET Livelihoods Analyst, and Emma Willenborg, FEWS NET Livelihoods Research Assistant. This report will form part of the knowledge base for FEWS NET’s food security monitoring activities in Nigeria. The publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006, Task Order 1 (AID-OAA-TO-12- 00003), TO4 (AID-OAA-TO-16-00015).