Flying Fish. Catalina Island California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

Yeoman Due Tomorrow

Z- VOLUME 77 S72 OBERLIN OHIO TUESDAY MAY 24 1949 NUMBER 58 Navy Psychiatrist ODA Hears Horton Council Meets Assumes Blame To Determine Yeoman Due Tomorrow ForForrestal Leap Disclaim Famous Feats FROM UNITED PRESS FateofShansi WASHINGTON Capt George In an attempt to up Boasts clear all New Art Section V top Navy psychiatrist Raines unfinished business responsibility today for at its final took full tl meeting tonight the Student the tnai made pos circumstances Council will take action on the sible James Forrestals suicide I Shansi allotment the remainder of nos Raines said he ordered the the Activity Fee allotments For- Report States Seven Newcomers Contribute um Board chairmanship appoint- because he felt such treatment was ment and will discuss a request Radio Station Smith Two Millers necessary if the former Defense for funds for an Oberlin radio Featured Secretary was to be cured of the station and the Council program psychoneurotic depressive condi for next year To Cost 600 By CHARLIE BLACKWELL tion he was sunenng ine psy The main discussion on Shansi Featuring an art section an experiment never before acknowledged chiatrist that the according to Henderson will cen- attempted in its history the 40- page Spring edition of the The minimum amount necessary treatment he prescribed involved ter around getting full information Yeoman will appear tomorrow according to Editor to build the proposed College Jonah a calculated risk of suicide He about the school Since the Coun- Kalb attributed Forrestals death leap cil desires Ur represent -

Poetry Magazine

Poetry Magazine 2008- January Articles Made to Measure, The Red Sea Devotion: The Garment District Nocturnal, Divine Rights Devotion: The Burnt-Over District Stephen Edgar Bruce Smith callas lover, cruel, cruel summer The History of Mothers of Sons D.A. Powell Lisa Furmanski Man of War, Argonaut's Vow Pink Ocean Carol Frost Stuart Dybek The Solipsist The Taste of Silence Troy Jollimore Adam Kirsch Citation Responsibilities Joshua Mehigan Joanie V. Mackowski Repetition,The Late Worm, Clamor and Quiet Cut Out For It Ange Mlinko Kay Ryan Closing the Circle Getting Where We're Going Jhumpa Lahiri John Brehm A Night in Brooklyn The Dead Remember Brooklyn The Rain-Streaked Avenues of Central Queens D. Nurkse Moose Dreams, Dogwood William Johnson Biographer Samuel Menashe La Porte Rachel Webster There's Nothing More Wendy Videlock Poetry Magazine 2008- Feb. Articles Midsummer, Dawn Leaving Prague: A Notebook Louise Glück Alexei Tsvetkov bon bon il est un pays, Mort de A.D. Four Takes à elle l’acte calme, Ascension D. H. Tracy La Mouche, Arènes de Lutèce Samuel Beckett Letter to the Editor James Matthew Wilson Fowling Piece Heidy Steidlmayer Letter to the Editor Sean Lysaght An Old Woman’s Painting Letter to the Editor Jim Carmin Lynn Emanuel Letter to the Editor Michael Hudson Full Fathom Jorie Graham Letter to the Editor Robert Longoni J. Learns the Difference Between Letter to the Editor Adam Zagajewski Poverty and Having No Money Jeffrey Schultz Stemming from Stevens Lisa Williams Ladybirds Larissa Szporluk Rose Thorns Molly McQuade Kertész: Latrine,Ross: Children of the Ghetto,Ross: Yellow Star Doisneau: Underground Press Sudek: Tree Petersen: Kleichen and a Man Kolár: Housing Estate George Szirtes Sincerity and Its Discontents in American Poetry Now Peter Campion Poetry Magazine 2008- March Articles Nights on Planet Earth Campbell McGrath Letter to the Editor William Watt Containment, The Catch Letter to the Editor Michael A.E. -

Oberlin Historic Landmarks Booklet

Oberlin Oberlin Historic Landmarks Historic Landmarks 6th Edition 2018 A descriptive list of designated landmarks and a street guide to their locations Oberlin Historic Landmarks Oberlin Historic Preservation Commission Acknowledgments: Text: Jane Blodgett and Carol Ganzel Photographs for this edition: Dale Preston Sources: Oberlin Architecture: College and Town by Geoffrey Blodgett City-wide Building Inventory: www.oberlinheritage.org/researchlearn/inventory Published 2018 by the Historic Preservation Commission of the City of Oberlin Sixth edition; originally published 1997 Oberlin Historic Preservation Commission Maren McKee, Chair Michael McFarlin, Vice Chair James Young Donna VanRaaphorst Phyllis Yarber Hogan Kristin Peterson, Council Liaison Carrie Handy, Staff Liaison Saundra Phillips, Secretary to the Commission Introduction Each building and site listed in this booklet is an officially designated City of Oberlin Historic Landmark. The landmark designation means, according to city ordinance, that the building or site has particular historic or cultural sig- nificance, or is associated with people or events important to the history of Oberlin, Ohio, or reflects distinguishing characteristics of an architect, archi- tectural style, or building type. Many Oberlin landmarks meet more than one of these criteria. The landmark list is not all-inclusive: many Oberlin buildings that meet the criteria have not yet been designated landmarks. To consider a property for landmark designation, the Historic Preservation Commission needs an appli- cation from its owner with documentation of its date and proof that it meets at least one of the criteria. Some city landmarks are also listed on the National Register of Historic Plac- es, and three are National Historic Landmarks. These designations are indicat- ed in the text. -

Hammer Langdon Cv18.Pdf

LANGDON HAMMER Department of English [email protected] Yale University jamesmerrillweb.com New Haven CT 06520-8302 yale.edu bio page USA EDUCATION Ph.D., English Language and Literature, Yale University B.A., English Major, summa cum laude, Yale University ACADEMIC APPOINTMENT Niel Gray, Jr., Professor of English and American Studies, Yale University Appointments in the English Department at Yale: Lecturer Convertible, 1987; Assistant Professor, 1989; Associate Professor with tenure, 1996; Professor, 2001; Department Chair, 2005-fall 2008, Acting Department Chair, fall 2011 and fall 2013, Department Chair, 2014-17 and 2017-19 PUBLICATIONS Books In progress: Elizabeth Bishop: Life & Works, A Critical Biography (under contract to Farrar Straus Giroux) The Oxford History of Poetry in English (Oxford UP), 18 volumes, Patrick Cheney general editor; LH coordinating editor for Volumes 10-12 on American Poetry, and editor for Volume 12 The Oxford History of American Poetry Since 1939 The Selected Letters of James Merrill, edited by LH, J. D. McClatchy, and Stephen Yenser (under contract to Alfred A. Knopf) Published: James Merrill: Poems, Everyman’s Library Pocket Poets, selected and edited with a foreword by LH (Penguin RandomHouse, 2017), 256 pp James Merrill: Life and Art (Alfred A. Knopf, 2015), 944 pp, 32 pp images, and jamesmerrillweb.com, a website companion with more images, bibliography, documents, linked reviews, and blog Winner, Lambda Literary Award for Gay Memoir/Biography, 2016. Finalist for the Poetry 2 Foundation’s Pegasus Award for Poetry Criticism, 2015. Named a Times Literary Supplement “Book of the Year, 2015” (two nominations, November 25). New York Times, “Top Books of 2015” (December 11). -

Five Kingdoms

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2008 Five Kingdoms Kelle Groom University of Central Florida Part of the Creative Writing Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Groom, Kelle, "Five Kingdoms" (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3519. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3519 FIVE KINGDOMS by KELLE GROOM M.A. University of Central Florida, 1995 B.A. University of Central Florida, 1989 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing/Poetry in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2008 Major Professor: Don Stap © 2008 Kelle Groom ii ABSTRACT GROOM, KELLE . Five Kingdoms. (Under the direction of Don Stap.) Five Kingdoms is a collection of 55 poems in three sections. The title refers to the five kingdoms of life, encompassing every living thing. Section I explores political themes and addresses subjects that reach across a broad expanse of time—from the oldest bones of a child and the oldest map of the world to the bombing of Fallujah in the current Iraq war. Connections between physical and metaphysical worlds are examined. -

A Tradition of Excellence Continues

The Newsletter of the Creative Writing Program at the University of Houston WWW.UH.EDU/CWP A Tradition of Excellence Continues: John Antel Dean, CLASS Wyman Herendeen English Dept. Chair j. Kastely CWP Director Kathy Smathers Assistant Director Shatera Dixon Program Coordinator 713.743.3015 [email protected] This year we welcome two new and one visiting faculty member—all are exciting writers; all are compelling teachers. 2006-2007 Edition Every effort has been made to include faculty, students, and alumni news. Items not included will be published in the next edition. As we begin another academic year, I am struck by how much change the Program has endured in the past year. After the departure of several faculty members the previous year, we have hired Alexander Parsons and Mat John- son as new faculty members in fiction into tenure track positions, and we also hired Liz Waldner as a visitor in poetry for the year. Our colleague, Daniel Stern, passed away this Spring, and he will be missed. Adam Zagajew- ski will take a visiting position in the Committee on Social Thought at the University of Chicago this year, and that Committee will most likely become his new academic home. Ed Hirsh submitted his letter of resignation this Spring, and although Ed had been in New York at the Guggenheim for the last five years, he had still officially been a member of the Creative Writing Program on leave. And Antonya Nelson returned from leave this Spring to continue her teaching at UH. So there has been much change. -

1 Creative Expression in Writing (EGL 32 W)

Creative Expression in Writing (EGL 32 W) - Preliminary Syllabus Instructor: Brittany Perham Term: Fall 2015 Required Materials 1. Great American Prose Poems: From Poe to the Present, edited by David Lehman ISBN-13: 978-0743243506 Available at Powell’s Books here: GAPP Available at Amazon.com here: GAPP 2. Short Takes: Brief Encounters with Contemporary Nonfiction, edited by Judith Kitchen ISBN-13: 978-0393326000 Available at Powell’s Books here: Short Takes Available at Amazon.com here: Short Takes 3. Sudden Fiction: American Short-Short Stories, edited by Robert Shepard & James Thomas ISBN-13: 978-0879052652 Available at Powell’s Books here: Sudden Fiction Available at Amazon.com here: Sudden Fiction 4. Online reading (posted online in the form of links) 5. Handouts (posted online in the form of .pdf files) The Online Community The fabulous thing about the Online Writers’ Studio is that it brings together like-minded people from all over the world. Together we will form a community of writers who will challenge and support each other. This is your class. Grading Most students enroll in this course under the non-graded (NGR) or the Credit/No Credit (i.e. pass/fail) options. If you would prefer to be graded, or if you must receive a letter grade to meet the requirements of your academic program, participation will serve as the basis of your grade. In order to receive an A, you must turn in all three pieces of writing for workshop, fulfill your responsibilities as workshop member, and participate thoughtfully in class discussion. If you complete less than 60% of the course work on time, you will receive an F. -

Penguin Anthology = of = Twentieth- Century American Poetry

SUB Hamburg 111 THE A 2011/11828 PENGUIN ANTHOLOGY = OF = TWENTIETH- CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY EDITED WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY RITA DOVE PENGUIN BOOKS Contents Introduction by Rita Dove xxix Edgar Lee Masters (1868-1950) FROM Spoon River Anthology: The Hill • 1 Fiddler Jones • 2 Petit, the Poet • 3 Edwin Arlington Robinson (1869-1935) Miniver Cheevy • 4 Mr. Flood s Party • 5 James WeldonJohnson (1871-1938) The Creation • 7 Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906) 10 The Poet • 10 Life's Tragedy • 10 Robert Frost (1874-1963) 12 The Death of the Hired Man • 12 Mending Wall • 17 Birches • 18 Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening • 20 Tree at My Window • 20 Directive • 21 CONTENTS Amy Lowell (1874-1925) 23 Patterns • 23 Gertrude Stein (1874-1946) 26 Susie Asado • 26 FROM Tender Buttons: A Box • 26 A Plate • 27 Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson (1875-1935) 28 I Sit and Sew • 28 Carl Sandburg (1878-1967) 29 Grass • 29 Cahoots • 29 Wallace Stevens (1879-1955) 31 Peter Quince at the Clavier • 31 Disillusionment of Ten O'Clock • 33 Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird • 34 Anecdote of the Jar • 36 The Emperor of Ice-Cream • 36 Of Mere Being • 36 Angelina Weld Grimke (1880-1958) 38 Fragment • 38 William Carlos Williams (1883-1963) 39 Tract • 39 DanseRusse • 41 The Red Wheelbarrow • 41 The Yachts • 42 FROM Asphodel, That Greeny Flower (Book I, lines 1-92) • 43 SaraTeasdale (1884-1933,) 51 Moonlight • 51 There Will Come Soft Rains • 51 CONTENTS Ezra Pound (1885-1972) 53 The Jewel Stairs' Grievance • 53 The River-Merchant's Wife: A Letter • 53 In a Station of the -

P R O S P E C T

PROSPECTUS CHRIS ABANI EDWARD ABBEY ABIGAIL ADAMS HENRY ADAMS JOHN ADAMS LÉONIE ADAMS JANE ADDAMS RENATA ADLER JAMES AGEE CONRAD AIKEN DANIEL ALARCÓN EDWARD ALBEE LOUISA MAY ALCOTT SHERMAN ALEXIE HORATIO ALGER JR. NELSON ALGREN ISABEL ALLENDE DOROTHY ALLISON JULIA ALVAREZ A.R. AMMONS RUDOLFO ANAYA SHERWOOD ANDERSON MAYA ANGELOU JOHN ASHBERY ISAAC ASIMOV JOHN JAMES AUDUBON JOSEPH AUSLANDER PAUL AUSTER MARY AUSTIN JAMES BALDWIN TONI CADE BAMBARA AMIRI BARAKA ANDREA BARRETT JOHN BARTH DONALD BARTHELME WILLIAM BARTRAM KATHARINE LEE BATES L. FRANK BAUM ANN BEATTIE HARRIET BEECHER STOWE SAUL BELLOW AMBROSE BIERCE ELIZABETH BISHOP HAROLD BLOOM JUDY BLUME LOUISE BOGAN JANE BOWLES PAUL BOWLES T. C. BOYLE RAY BRADBURY WILLIAM BRADFORD ANNE BRADSTREET NORMAN BRIDWELL JOSEPH BRODSKY LOUIS BROMFIELD GERALDINE BROOKS GWENDOLYN BROOKS CHARLES BROCKDEN BROWN DEE BROWN MARGARET WISE BROWN STERLING A. BROWN WILLIAM CULLEN BRYANT PEARL S. BUCK EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS OCTAVIA BUTLER ROBERT OLEN BUTLER TRUMAN CAPOTE ERIC CARLE RACHEL CARSON RAYMOND CARVER JOHN CASEY ANA CASTILLO WILLA CATHER MICHAEL CHABON RAYMOND CHANDLER JOHN CHEEVER MARY CHESNUT CHARLES W. CHESNUTT KATE CHOPIN SANDRA CISNEROS BEVERLY CLEARY BILLY COLLINS INA COOLBRITH JAMES FENIMORE COOPER HART CRANE STEPHEN CRANE ROBERT CREELEY VÍCTOR HERNÁNDEZ CRUZ COUNTEE CULLEN E.E. CUMMINGS MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM RICHARD HENRY DANA JR. EDWIDGE DANTICAT REBECCA HARDING DAVIS HAROLD L. DAVIS SAMUEL R. DELANY DON DELILLO TOMIE DEPAOLA PETE DEXTER JUNOT DÍAZ PHILIP K. DICK JAMES DICKEY EMILY DICKINSON JOAN DIDION ANNIE DILLARD W.S. DI PIERO E.L. DOCTOROW IVAN DOIG H.D. (HILDA DOOLITTLE) JOHN DOS PASSOS FREDERICK DOUGLASSOur THEODORE Mission DREISER ALLEN DRURY W.E.B. -

English 3150: Intermediate Poetry Workshop University of North Texas Spring 2016 3150.001 TR 12:30-1:50 Pm AUDB 201

English 3150: Intermediate Poetry Workshop University of North Texas Spring 2016 3150.001 TR 12:30-1:50 pm AUDB 201 Dr. Anne Keefe Email: [email protected] Office: LANG 408A Office Hours: TR 8:15-9:15 am W 1-2 pm “It is the pleasure of the workshop that everyone there gets to be a part of such moments of sweetness, when there appears at last a poem that is fine and shapely, where before there was only struggle, and the tangled knot of words. We all partake, then, a little, of the miracle, that is made not only of luck and inspiration and even happenstance, but of those other matters too— technical knowledge and diligent work—matters that are less interesting perhaps, but altogether essential, for such things support the ineffable and moving light of the poem: they are the bedrock of the river.” --Mary Oliver, A Poetry Handbook Description This course is an intermediate level workshop focusing on the craft of poetry writing. We will engage the art of poetry through technical exercises in sound, meter, form, image, and voice. Structured in a workshop environment, the class discussion will center on student-created texts, with supplemental readings from contemporary poets, and culminate with a final portfolio of revised work. Required Texts Mary Oliver, A Poetry Handbook: A Prose Guide to Understanding and Writing Poetry (ISBN: 9780156724005) Additional course readings will be provided in our course reader, which I will distribute on the first day of class, or as handouts. Electronic versions of all readings will also posted on our Blackboard site. -

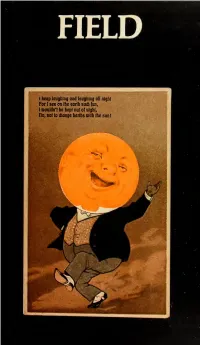

For I See on the Earth Sudh Lun, I Moiit&

FIELD I fwep laiightiig aod iaugbing aff night For I see on the earth sudh lun, I moiit&’t be hept out of s|gbt« no, FIELD CONTEMPORARY POETRY AND POETICS NUMBER 17 - FALL 1977 PUBUSHED BY OBERLIN COLLEGE OBERUN, OHIO EDITORS Stuart Friebert David Young ASSOCIATE Patricia Ikeda EDITORS David St. John Alberta Turner EDITORIAL Reina Calderon ASSISTANT COVER Steve Parkas FIELD gratefully acknowledges support from the Ohio Arts Council, the Coordinating Council of Literary Magazines, Laurence Perrine, and Ann Moyer Seaman. Published twice yearly by Oberlin College. Subscriptions: $4.00 a year / $7.00 for two years / Single is- sues $2.00 postpaid. Back issues 1-9; 11-14: $10.00. Issue 10 is out of print. Issues 15 & 16 are still available at $2.00 each. Subscription orders and manuscripts should be sent to FIELD, Rice Hall, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio 44074. Manu- scripts will not be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. Copyright © 1977 by Oberlin College. CONTENTS Zbigniew Herbert 5 The Ardennes Forest 7 A Little Box Called Imagination Larry Levis 8 For Zbigniew Herbert, Summer, 1971, Los Angeles 9 Words for the Axe 10 The Future of Hands C. D. Wright 13 Woman Looking through a Viewmaster 14 Amnesiac 15 The End at the Bathhouse Leslie Rondin 17 Come Put Your Hand 18 Heraclitus Linda Gregerson 19 Rain Mark Jarman 20 Required Mysteries 22 My Parents Have Come Home Laughing Debra Bruce 23 For Bad Grandmother and Betty Bumhead Steve Orlen 24 The Question Was Franz Wright 25 St. Paul’s Greek Orthodox Church Minneapolis,