Transcript, on the Road

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

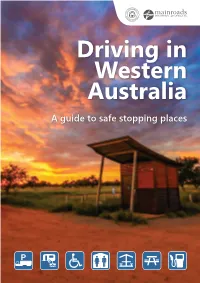

Driving in Wa • a Guide to Rest Areas

DRIVING IN WA • A GUIDE TO REST AREAS Driving in Western Australia A guide to safe stopping places DRIVING IN WA • A GUIDE TO REST AREAS Contents Acknowledgement of Country 1 Securing your load 12 About Us 2 Give Animals a Brake 13 Travelling with pets? 13 Travel Map 2 Driving on remote and unsealed roads 14 Roadside Stopping Places 2 Unsealed Roads 14 Parking bays and rest areas 3 Litter 15 Sharing rest areas 4 Blackwater disposal 5 Useful contacts 16 Changing Places 5 Our Regions 17 Planning a Road Trip? 6 Perth Metropolitan Area 18 Basic road rules 6 Kimberley 20 Multi-lingual Signs 6 Safe overtaking 6 Pilbara 22 Oversize and Overmass Vehicles 7 Mid-West Gascoyne 24 Cyclones, fires and floods - know your risk 8 Wheatbelt 26 Fatigue 10 Goldfields Esperance 28 Manage Fatigue 10 Acknowledgement of Country The Government of Western Australia Rest Areas, Roadhouses and South West 30 Driver Reviver 11 acknowledges the traditional custodians throughout Western Australia Great Southern 32 What to do if you breakdown 11 and their continuing connection to the land, waters and community. Route Maps 34 Towing and securing your load 12 We pay our respects to all members of the Aboriginal communities and Planning to tow a caravan, camper trailer their cultures; and to Elders both past and present. or similar? 12 Disclaimer: The maps contained within this booklet provide approximate times and distances for journeys however, their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Main Roads reserves the right to update this information at any time without notice. To the extent permitted by law, Main Roads, its employees, agents and contributors are not liable to any person or entity for any loss or damage arising from the use of this information, or in connection with, the accuracy, reliability, currency or completeness of this material. -

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Question on Notice

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Question On Notice Wednesday, 10 October 2018 1687. Hon Robin Chapple to the Minister for Environment representing the Minister for Lands In relation to the Govemment's support for carbon sequestration proj ects on Westem Australia's pastoral leases, I ask: (a) which carbon sequestration project methods approved under the Federal Government's Emissions Reduction Fund fall within the definition of 'pastoral purposes' as outlined under Westem Australia's Land Administration Act 1997; (b) when does the Govemment expect it will be in a position to start providing eligible interest holder consent for carbon sequestration projects on pastoral leases; (c) is the Govemment considering providing consent for all carbon sequestration projects that have been provisionally registered with the Emissions Reduction Fund, or only those projects that have been successful in securing contracts to supply carbon credits to tile Federal Govemment; (d) is the Govemment aware that by 1 July 2019, over 20 per cent of Westem Australian pastoral leases will have te=s that are less than 25 years, and that consequently under current legislation, pastoralists and other leaseholders will be unable to register a carbon sequestration proj ect because they require tenure of at least 25 years duration; (e) what are the names of the pastoral leases and the regions in which they are situated that, at 1 July 2019, will have 25 years or less of their terms left to run; (f) of the leases listed in (e), how many are Aboriginal-owned; (g) will the Govemment provide for leaseholders to undertake carbon sequestration proj ects of a duration of 100 years which is the intemationally accepted and compliant standard; and (h) if yes to (g), what tenure will provide for such projects? Answer (a) To date, the State of West em Australia has only formally considered the approved Human-Induced Regeneration of a Pel111anent Even-Aged Native Forest method, in te=s of consistency with 'pastoral purposes' as defmed within Part 7 of the Land Administration Act 1997. -

Mingalkala Layout Plan 1 Background Report

Mingalkala Layout Plan 1 Background Report September 2005 Date endorsed by WAPC Amendments Amendment 1 - April 2013 Amendment 2 - August 2018 Amendment 3 - July 2020 MINGALKALA LAYOUT PLAN 1 Layout Plan 1 (LP1) was prepared during 2005 by Sinclair Knight Merz. LP1 has been endorsed by the resident community (25 July 2005), the Shire of Halls Creek (25 August 2005) and the Western Australian Planning Commission (WAPC) (27 September 2005). During the period April 2013 until August 2018 the WAPC endorsed 2 amendments to LP1. The endorsed amendments are listed in part 7 of this report. Both amendments were map-set changes, with no changes made to the background report. Consequently, the background report has become out-of-date, and in June 2020 it was updated as part of Amendment 3. The Amendment 3 background report update sought to keep all relevant information, while removing and replacing out-of-date references and data. All temporal references in the background report refer to the original date of preparation, unless otherwise specified. As part of the machinery of government (MOG) process, a new department incorporating the portfolios of Planning, Lands, Heritage and Aboriginal lands and heritage was established on 1st of July 2017 with a new department title, Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage. Since the majority of this report was finalised before this occurrence, the Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage will be referred to throughout the document. Other government departments mentioned throughout this document will be referred to by their department name prior to the 1st of July 2017. Mingalkala Layout Plan No. -

Ockham's Razor

The Journal of the European Association for Studies of Australia, Vol.4 No.1, 2013. Reading Coolibah’s Story: As told by Coolibah to John Boulton John Boulton Copyright © John Boulton 2013. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged. Abstract: This paper describes selected key events in the life of Coolibah, a retired Gurindji stockman, through his non-Aboriginal friend John Boulton. Coolibah made John “a close friend of the same age”, referred to specifically as tjimerra in Gooniyandi language (the language that he has become most familiar with since being removed from his family as a small child). This classifactory kin relationship makes it possible for John Boulton to tell Coolibah’s story. This article is situated within the tradition of oral histories of the lives of Aboriginal people at the colonial frontier. It is also within a tradition of friendships between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, including European, people, often anthropologists and other professionals with a deep commitment to that world. In this article, Boulton uses the events of Coolibah’s life and that of his family and kin as a departure point to discuss the impact of history on the health of the people. Coolibah’s life is viewed through the lens of structural violence whereby the causal factors for the gap in health outcomes have been laid down. This article provides the theoretical framework to understand the extent of psychic, emotional and physical harm perpetrated on generations of Aboriginal people from the violent collision of the two worlds on the Australian frontier. -

An Annotated Type Catalogue of the Dragon Lizards (Reptilia: Squamata: Agamidae) in the Collection of the Western Australian Museum Ryan J

RECORDS OF THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM 34 115–132 (2019) DOI: 10.18195/issn.0312-3162.34(2).2019.115-132 An annotated type catalogue of the dragon lizards (Reptilia: Squamata: Agamidae) in the collection of the Western Australian Museum Ryan J. Ellis Department of Terrestrial Zoology, Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC, Western Australia 6986, Australia. Biologic Environmental Survey, 24–26 Wickham St, East Perth, Western Australia 6004, Australia. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT – The Western Australian Museum holds a vast collection of specimens representing a large portion of the 106 currently recognised taxa of dragon lizards (family Agamidae) known to occur across Australia. While the museum’s collection is dominated by Western Australian species, it also contains a selection of specimens from localities in other Australian states and a small selection from outside of Australia. Currently the museum’s collection contains 18,914 agamid specimens representing 89 of the 106 currently recognised taxa from across Australia and 27 from outside of Australia. This includes 824 type specimens representing 45 currently recognised taxa and three synonymised taxa, comprising 43 holotypes, three syntypes and 779 paratypes. Of the paratypes, a total of 43 specimens have been gifted to other collections, disposed or could not be located and are considered lost. An annotated catalogue is provided for all agamid type material currently and previously maintained in the herpetological collection of the Western Australian Museum. KEYWORDS: type specimens, holotype, syntype, paratype, dragon lizard, nomenclature. INTRODUCTION Australia was named by John Edward Gray in 1825, The Agamidae, commonly referred to as dragon Clamydosaurus kingii Gray, 1825 [now Chlamydosaurus lizards, comprises over 480 taxa worldwide, occurring kingii (Gray, 1825)]. -

Koongie Park Layout Plan 2 Background Report

Koongie Park Layout Plan 2 Background Report September 2011 Date endorsed by WAPC Amendments Amendment 1 - September 2012 Amendment 2 - October 2012 Amendment 3 - January 2013 Amendment 4 - November 2013 Amendment 5 - October 2018 Amendment 6 - February 2019 Amendment 7 - May 2020 KOONGIE PARK LAYOUT PLAN 2 This background report was prepared between 2009 and 2010 by Aurecon in partnership with the Koongie Elvira Aboriginal Corporation (KEAC). Layout Plan 2 (LP2) was endorsed by KEAC on 30 November 2010. The Western Australian Planning Commission (WAPC) endorsed the LP on 29 September 2011. During the period September 2011 to February 2019 the WAPC endorsed 6 amendments to LP1. The endorsed amendments are listed in Part 7 of this report. All of the amendments were map-set changes, with no changes made to the background report. In May 2020 the background report was updated as a part of Amendment 7. The Amendment 7 background report update sought to keep all relevant information, while removing and replacing out-of-date references and data. All temporal references in the background report refer to the original date of preparation, unless otherwise specified. As part of the machinery of government (MOG) process, a new department incorporating the portfolios of Planning, Lands, Heritage and Aboriginal lands and heritage was established on 1st of July 2017 with a new department title, Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage. Since the majority of this report was finalised before this occurrence, the Department of Planning, Lands and Heritage will be referred to throughout the document. Other government departments mentioned throughout this document will be referred to by their department name prior to the 1st of July 2017. -

East Kimberley Impact Assessment Project

East Kimberley Impact Assessment Project HISTORICAL NOTES RELEVANT TO IMPACT STORIES OF THE EAST KIMBERLEY Cathie Clement* East Kimberley Working Paper No. 29 ISBN O 86740 357 8 ISSN 0816...,6323 A Joint Project Of The: Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies Australian National University Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies Anthropology Department University of Western Australia Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia The aims of the project are as follows: 1. To compile a comprehensive profile of the contemporary social environment of the East Kimberley region utilising both existing information sources and limited fieldwork. 2. Develop and utilise appropriate methodological approaches to social impact assessment within a multi-disciplinary framework. 3. Assess the social impact of major public and private developments of the East Kimberley region's resources (physical, mineral and environmental) on resident Aboriginal communities. Attempt to identify problems/issues which, while possibly dormant at present, are likely to have implications that will affect communities at some stage in the future. 4. Establish a framework to allow the dissemination of research results to Aboriginal communities so as to enable them to develop their own strategies for dealing with social impact issues. 5. To identify in consultation with Governments and regional interests issues and problems which may be susceptible to further research. Views expressed in the Projecfs publications are the views of the authors, and are not necessarily shared by the sponsoring organisations. Address correspondence to: The Executive Officer East Kimberley Project CRES, ANU GPO Box4 Canberra City, ACT 2601 HISTORICAL NOTES RELEVANT TO IMPACT STORIES OF THE EAST KIMBERLEY Cathie Clement* East Kimberley Working Paper No. -

Table 1: Clearing Permit Applications, Including Amended Applications, for Clearing Within Pastoral Leases Within the Kimberley Land Division

Table 1: Clearing Permit applications, including amended applications, for clearing within pastoral leases within the Kimberley Land Division Application Hectares number Lease name Permit holder applied 7270/1 ANNA PLAINS Anna Plains Cattle Co Pty Ltd 120 6593/1 FLORA VALLEY Northern Minerals Ltd 127.1 6828/1 GIBB RIVER Shire of Wyndham East Kimberley 469 4501/2 GOGO Gogo Station Pty Ltd 723 6663/1 GORDON DOWNS Northern Minerals Ltd 127.1 Argyle Concrete and Quarry Suppliers Pty 7854/1 IVANHOE Ltd 4 2892/3 IVANHOE Main Roads Western Australia 60 818/12 IVANHOE Main Roads Western Australia 30 2892/2 IVANHOE Main Roads Western Australia 60 4661/3 IVANHOE Mr Ken Spurge 16.85 6318/1 KILTO Jamie Burton 142.5 3129/2 KIMBERLEY DOWNS Kimberley Diamond Company NL 364 7906/1 KIMBERLEY DOWNS POZ Minerals Limited 80 6787/1 LARRAWA Mr Kevin Brockhurst 6.98 7345/1 LISSADELL Baldy Bay Pty Ltd 150 7345/2 LISSADELL Baldy Bay Pty Ltd 147 6739/1 MARGARET RIVER Yougawalla Pastoral Co Pty Ltd 426 6280/1 MOOLA BULLA SAWA Pty Ltd 28.035 6084/2 MOWANJUM Mowanjum Aboriginal Corporation 76 6084/3 MOWANJUM Mowanjum Aboriginal Corporation 223 6084/4 MOWANJUM Mowanjum Aboriginal Corporation 116 6084/5 MOWANJUM Mowanjum Aboriginal Corporation 116 6084/1 MOWANJUM Mowanjum Aboriginal Corporation 76 7557/1 MT ANDERSON Department of Water 1 6556/1 NAPIER DOWNS Mr David Martin 12.435 7122/1 NITA DOWNS Forshaw Pastoral Company Pty Ltd 250 7342/1 NITA DOWNS Forshaw Pastoral Company Pty Ltd 200 7864/1 NOONKANBAH Department of Communities 1.2 7315/1 NOONKANBAH Noonkanbah Rural -

Nth Past Memo June 2007.Pmd

PastoralPastoral MEMOMEMO © State of Western Australia, 2007. Northern Pastoral Region PO Box 19, Kununurra WA 6743 Phone: (08) 9166 4019 E-mail: [email protected] June 2007 ISSN 1033-5757 Vol. 28, No. 2 CONTENTS Where has the rain been falling? ........................................................................................................... 2 Welcome from the Editor ....................................................................................................................... 3 Kimberley and Pilbara ‘wet’ season round-up ........................................................................................ 4 Halls Creek Judas Donkey Program ...................................................................................................... 5 Alan Lawford to attend Australian Rural Leadership Program ................................................................. 6 Profitability and sustainability of Indigenous owned pastoral businesses ................................................ 6 Increase in Pastoral Water Grants ........................................................................................................11 Road trip ...............................................................................................................................................11 Horse movements ................................................................................................................................12 Bush Nurse ......................................................................................................................................... -

Single Column Report

North Kimberley subregion overview and future directions Kimberley regional water plan working discussion paper Looking after all our water needs Department of Water October 2009 Department of Water 168 St Georges Terrace Perth Western Australia 6000 Telephone +61 8 6364 7600 Facsimile +61 8 6364 7601 www.water.wa.gov.au © Government of Western Australia 2009 September 2009 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non- commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Department of Water. ISBN 978-1-921675-10-2 (online) This discussion paper forms part of the Department of Water Kimberley regional water plan process. We have divided the Kimberley into six subregions: Ord catchment, Fitzroy catchment, and the Dampier Peninsula, North Kimberley, La Grange, and Desert subregions. As a working draft for the North Kimberley subregion, this paper requires review and input from stakeholders. It may contain omissions or outdated information so it should not be cited or used for other purposes outside of this planning process. The key issues identified in this draft paper have been drawn from a range of documents, forums and discussion with stakeholders. Coverage of these issues may not be comprehensive, so they will be reconsidered after consultation with key stakeholder groups. This discussion paper, and feedback provided by stakeholders, will be reworked and incorporated into the final Kimberley regional water plan. -

Collection Name: Halls Creek Shire Register

Pictorial collection name: Halls Creek Shire Register. A Photographic History 1995. Volume 9 Collection number: BA1343/14 Collection Item Photographer Caption Description Provided by Donor Date No. No. BA1343/14 /1 Derek Keene The Brockman This small portion of a stone hut, is 1995 ruins all that remains of a once thriving gold mining settlement, about 15 kilometres from old Halls Creek and twice that distance from the present townsite. In a 10 kilometre radius from this hut the greater portion of Halls Creek gold was discovered. This area was known famously as the Brockman and even today Aboriginal people come to this place to look for gold after a big storm or heavy rain, and they nearly always pick up specs of gold. BA1343/14 /2 Derek Keene Halls Creek Back row: Julie York - Clerk/Typist, 1995 police force Shannon Massam - 8803 First Class Constable, Geoff Cramp - 8364 First Class Constable, James McKenzie 143 First Class Police Aide, Kim Massam 8762 First Class Constable, Darryn Heath 7331 Senior Constable, Glenn Dewhurst 8239 First Class Constable, John Birch 8 Senior Police Aide, Charles Moylan 7009 Senior Constable. Front row: Terry Dobson 6453 Senior Constable, Philip Bell 4882 Sergeant, Jonathan Snow 8487 First Class Constable. BA1343/14 /3 Derek Keene Halls Creek Back row: Simon McGlasson - 1995 Shire - Councillor, William (Bill) Atyeo - Councillors PEHO (Principal Environmental and Health Officer), Peter McConnell - Administrative Financial Controller, Christopher Staff. William (Bill) Molloy - Assistant Shire Clerk, Dennis Mangan - Councillor. Front row: Philip Foster - Shire Clerk, Warren Dallachy - Councillor and Deputy President, BA1343/14 1 Copyright SLWA ©2014 Collection Item Photographer Caption Description Provided by Donor Date No. -

Annual Report of the Commissioner of Native Affairs for the Year Ended 30Th June 1951

1953 WESTERN AUSTRALIA ANNUAL REPORT of the Commissioner of Native Affairs for the YEAR ENDED 30th JUNE, 1951. 2 8 AUG 1963 PERTH: By Authority: WILLIAM H. WYATT, Government Printer. 59832/52. 1953. Digitised by AIATSIS Library 2008 - www.aiatsis.gov.au/library Index. Page. INTRODUCTION 4 SECTION " A "—DISTRICT WELFARE REPORTS— Central District—B. A. McLarty, Esq., District Officer 6 Southern District—C. R. Wright Webster, Esq., District Officer 11 North-West District—J. J. Rhatigan, Esq., District Officer 15 SECTION " B "—DEPARTMENTAL INSTITUTIONS— La Grange Bay Ration Depot, via Broome 16 East Perth Girls' Home, Bennett Street, East Perth 16 Marribank Farm School, via Katanning 16 Moore River Native Settlement, via Mogumber .... 17 Moola Bulla Native Station, via Hall's Creek 17 Alvan House, Mt. Lawley 18 Cosmo Newbery Native Settlement, via Laverton 19 SECTION " C "—MISSIONS— General Remarks 20 United Aborigines Mission—West Australian Council 21 United Aborigines Mission—Mt. Margaret Mission, Mt. Margaret 22 United Aborigines Mission—Sunday Island Mission, via Verby 23 United Aborigines Mission—Kellerberrin Mission, Kellerberrin .... .... .... 24 Pallotine (Roman Catholic) Order—Beagle Bay Mission, via Broome 25 Pallotine (Roman Catholic) Order—Balgo Mission, via Hall's Creek 26 Presbyterian Mission—Kunmunya-Wotjulum Mission, via Yampi 26 Roelands Native Mission Farm (Inc.), Rowlands 27 Federal Aborigines Mission Board (Churches of Christ)—Norseman Mission, Norseman 29 Federal Aborigines Mission Board (Churches of Christ)—Carnarvon