DIDI JI with Pictures.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Love Is a Metaphor: 99 Metaphors of Love

LOVE IS A METAPHOR: 99 METAPHORS OF LOVE https://www.thoughtco.com/love-is-a-metaphor-1691861 1. A Fruit Love is a fruit, in season at all times and within the reach of every hand. Anyone may gather it and no limit is set. (Mother Teresa, No Greater Love, 1997) 2. A Banana Peel I look at you and wham, I'm head over heels. I guess that love is a banana peel. I feel so bad and yet I'm feeling so well. I slipped, I stumbled, I fell. (Ben Weisman and Fred Wise, "I Slipped, I Stumbled, I Fell," sung by Elvis Presley in the film Wild in the Country, 1961) 3. A Spice Love is a spice with many tastes--a dizzying array of textures and moments. (Wayne Knight as Newman in the final episode of Seinfeld, 1998) 4. A Rose Love is a rose but you better not pick it. It only grows when it's on the vine. A handful of thorns and you'll know you've missed it. You lose your love when you say the word "mine."(Neil Young, "Love Is a Rose," 1977) 5. A Garden Now that you're gone I can see That love is a garden if you let it go. It fades away before you know, And love is a garden--it needs help to grow.(Jewel and Shaye Smith, "Love Is a Garden," 2008) 6. A Plant Love is a plant of the most tender kind, That shrinks and shakes with every ruffling wind. (George Granville, The British Enchanters, 1705) 7. -

Helena Mace Song List 2010S Adam Lambert – Mad World Adele – Don't You Remember Adele – Hiding My Heart Away Adele

Helena Mace Song List 2010s Adam Lambert – Mad World Adele – Don’t You Remember Adele – Hiding My Heart Away Adele – One And Only Adele – Set Fire To The Rain Adele- Skyfall Adele – Someone Like You Birdy – Skinny Love Bradley Cooper and Lady Gaga - Shallow Bruno Mars – Marry You Bruno Mars – Just The Way You Are Caro Emerald – That Man Charlene Soraia – Wherever You Will Go Christina Perri – Jar Of Hearts David Guetta – Titanium - acoustic version The Chicks – Travelling Soldier Emeli Sande – Next To Me Emeli Sande – Read All About It Part 3 Ella Henderson – Ghost Ella Henderson - Yours Gabrielle Aplin – The Power Of Love Idina Menzel - Let It Go Imelda May – Big Bad Handsome Man Imelda May – Tainted Love James Blunt – Goodbye My Lover John Legend – All Of Me Katy Perry – Firework Lady Gaga – Born This Way – acoustic version Lady Gaga – Edge of Glory – acoustic version Lily Allen – Somewhere Only We Know Paloma Faith – Never Tear Us Apart Paloma Faith – Upside Down Pink - Try Rihanna – Only Girl In The World Sam Smith – Stay With Me Sia – California Dreamin’ (Mamas and Papas) 2000s Alicia Keys – Empire State Of Mind Alexandra Burke - Hallelujah Adele – Make You Feel My Love Amy Winehouse – Love Is A Losing Game Amy Winehouse – Valerie Amy Winehouse – Will You Love Me Tomorrow Amy Winehouse – Back To Black Amy Winehouse – You Know I’m No Good Coldplay – Fix You Coldplay - Yellow Daughtry/Gaga – Poker Face Diana Krall – Just The Way You Are Diana Krall – Fly Me To The Moon Diana Krall – Cry Me A River DJ Sammy – Heaven – slow version Duffy -

Download Amy Winehouse Lioness

Download amy winehouse lioness CLICK TO DOWNLOAD 23/09/ · Amy Winehouse – Lioness: Hidden Treasures () {Japanese Edition} EAC Rip | FLAC Image + Cue + Log | Full Scans @ dpi, JPG Total Size: MB (CD) + MB (Scans) | 3% RAR Recovery Label: Universal Music, Japan | Cat#: UICI | Genre: R&B. The qualities of a vocal genius don’t always become clear when she’s singing classic material. Often as not, her abilities to both . 08/05/ · New Album Releases – download full albums, daily updates! Amy Winehouse – Lioness: Hidden Treasures () Sunday, July 19, Content feed; Comments Feed; Home; Contact Us; DCMA Policy; RSS Links; Archive. DownloadHits; Front; Top; Electronic; Folk; Indie; Jazz and Blues; Metal; Misc; Pop; Rap; Rock; Video; Amy Winehouse – Lioness: Hidden Treasures . download Amy Winehouse mp3: Stronger Than Me (Dj Devastate Rmx) 1: download Stronger Than Me (Dj Devastate Rmx) mp3: At The BBC: download At The BBC mp3: Lioness: Hidden Treasures (Japan) download Lioness: Hidden Treasures (Japan) mp3: Lioness: Hidden Treasures: download Lioness: Hidden Treasures mp3: Remix Demos Y Rarezas: 8/10(). Lioness: Hidden Treasures | Amy Winehouse to stream in hi-fi, or to download in True CD Quality on renuzap.podarokideal.ru Streaming plans Download store Magazine. Categories: All. Back. All. See all genres ON SALE NOW. Selections ; All playlists ; Hi-Res bestsellers ; Bestsellers ; New Releases ; As seen in the media ; Pre-orders ; Remastered Releases ; Qobuzissime ; The Qobuz Ideal Discography ; Qobuz 24 . New album Amy Winehouse - Lioness: Hidden Treasures () Vinyl available for download on site renuzap.podarokideal.ru 01/04/ · Amy Winehouse Discography Download | Format: Mp3 Kbps | Download: Mega | Disc: 16 CDs | Year: - | Genere: Pop / Country | Cou Discogc Discography FLAC (Lossless) HOME; FALLEN LINKS; DMCA; Amy Winehouse | Discography Kbps. -

4920 10 Cc D22-01 2Pac D43-01 50 Cent 4877 Abba 4574 Abba

ALDEBARAN KARAOKE Catálogo de Músicas - Por ordem de INTÉRPRETE Código INTÉRPRETE MÚSICA TRECHO DA MÚSICA 4920 10 CC I´M NOT IN LOVE I´m not in love so don´t forget it 19807 10000 MANIACS MORE THAN THIS I could feel at the time there was no way of D22-01 2PAC DEAR MAMA You are appreciated. When I was young 9033 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU A hundred days had made me older 2578 4 NON BLONDES SPACEMAN Starry night bring me down 9072 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP Twenty-five years and my life is still D36-01 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER AMNESIA I drove by all the places we used to hang out D36-02 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER HEARTBREAK GIRL You called me up, it´s like a broken record D36-03 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER JET BLACK HEART Everybody´s got their demons even wide D36-04 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT Simmer down, simmer down, they say we D43-01 50 CENT IN DA CLUB Go, go, go, go, shawty, it´s your birthday D54-01 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS I RAN I walk along the avenue, I never thought I´d D35-40 A TASTE OF HONEY BOOGIE OOGIE OOGIE If you´re thinkin´ you´re too cool to boogie D22-02 A TASTE OF HONEY SUKIYAKI It´s all because of you, I´m feeling 4970 A TEENS SUPER TROUPER Super trouper beams are gonna blind me 4877 ABBA CHIQUITITA Chiquitita tell me what´s wrong 4574 ABBA DANCING QUEEN Yeah! You can dance you can jive 19333 ABBA FERNANDO Can you hear the drums Fernando D17-01 ABBA GIMME GIMME GIMME Half past twelve and I´m watching the late show D17-02 ABBA HAPPY NEW YEAR No more champagne and the fireworks 9116 ABBA I HAVE A DREAM I have a dream a song to sing… -

English Unseen Poetry Booklet (First Four Only for Revision)

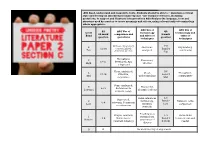

AO1 Read, understand and respond to texts. Students should be able to:• maintain a critical style and develop an informed personal response •use textual references, including quotations, to support and illustrate interpretations AO2 Analyse the language, form and structure used by a writer to create meanings and effects, using relevant subject terminology where appropriate. AO2 Use of AO2 Use of Q1 AO1 Use of Q2 Level terminology terminology and 24 mark comparison and 8 mark Band and effect of effect of question quotations question techniques techniques 7-8 6 Critical, exploratory, Judicious, Exploratory, 21-24 conceptualised; Band 4 Top analysed convincing Judicious, precise. Top Thoughtful, 5 Examined, 17-21 developed; Apt, High effective integrated Clear, explained; 5-6 4 Clear, Thoughtful, 13-16 Effective, Band 3 Mid understanding comparative supportive Mid Some explained; 3 Explained, 9-12 References to Low mid identified effects support, range Some references 3-4 Supported, 2 terminology, Band 2 Relevant, some 5-8 relevant; Comments Low Identifies Low comparison on references methods Possibly uses Simple, relevant; 1-2 Some links 1 terminology, 1-4 Reference to Band 1 between text and Bottom awareness of relevant detail(s) Bottom reader choices 0 0 No work worthy of any marks Are there groups of Narrative viewpoint How the sentence words that belong Repeated symbols structures or to a particular Sentence structure and specific punctuation punctuation semantic field? reflect feelings or Opening and Closing What difference emotions within the Semantic field does this make to text. How does it Rhythm the atmosphere of Timeframe change or develop? the text? Considering how the narrative choice Can you identify a enhances the Analysing rhythm to the text? meaning of the text STRUCTURE Is it written in a overall. -

The Cowl Is Here to Present Readers with on Sexual Proclivities,” but Rather Welcome That the Ideal Catholic Is a “Soldier” in the Stern Response” About the Matter

The• Vol. LXXXI No. 9 @thecowl thecowl.com ProvidenceCowl College November 10, 2016 Forty-Five Forty-Five President-Elect Donald Trump gives his victory speech after several hours of waiting for the final result of the race. PHOTO COURTESY OF LATIMES.COM by Katie Puzycki ’17 votes total. concession speech on Wednesday morning. powerful and deserving of every chance Editor-in-Chief Trump gave what some might consider A large concern for many of those against and opportunity in the world to pursue and a surprisingly presidential speech in a Trump presidency was how the nation to achieve your own dreams.” POLITICS comparison to some of his previous public would explain this election to minorities, While exit polls are still coming in, the appearances, driving-home the theme of children, immigrants, and refugees. In an most current results have proved just how After a nail-biting and cliff-hanging unity and “us.” In his victory speech, Trump emotional speech regarding this, CNN divided the nation currently is—a fine election night that trailed into the early reassured the American public that we “will correspondent Van Jones’ remarked, “You representation of the bipartisan struggle. hours of the morning, Donald J. Trump no longer settle for anything less than the tell your kids: Don’t be a bully … don’t They are so far suggesting that in many surpassed former Secretary of State and best.” Providing a visionary ideal for the be a bigot … do your homework and be areas republicans are as hard pressed Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton in a future Trump also remarked that, “We’re prepared. -

Anti-Valentines-Day-Playlist.Pdf

Anti-Valentine's Day LENGTH TITLE ARTIST bpm 4:32 Don't Cha The Pussycat Dolls 120 3:58 Say Something Loving The xx 130 3:03 This Is Not About Us Banks 100 Knowing Me, Knowing You (Almighty Definitive Radio 3:47 Edit) Abbacadabra 128 3:24 I Was a Fool Tegan and Sara 176 4:19 It Must Have Been Love Roxette 81 3:10 That's The Way Love Dies (feat. Tiger Rosa) Buck 65 170 3:11 Only War (feat. Tiger Rosa) Buck 65 168 3:42 Your Love Is A Lie Simple Plan 160 3:23 Bleeding Love - Vinylmoverz Hands Up Edit Swing State 136 4:14 Only Love Can Break Your Heart Jenn Grant 111 6:05 Hearts A Mess Gotye 125 4:22 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover G. Love & Special Sauce 92 3:42 Jealous Nick Jonas 93 I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For - 4:37 Remastered U2 101 3:07 Music Is My Hot, Hot Sex CSS 100 3:45 Foundations - Clean Edit Kate Nash 84 4:22 He Wasn't Man Enough Toni Braxton 88 3:49 Same Old Love Selena Gomez 98 3:34 Don't Wanna Know Maroon 5 100 5:20 Boy From School Hot Chip 126 5:48 Somebody Else The 1975 101 3:27 So Sick Ne-Yo 95 3:55 Sugar Maroon 5 120 3:42 Heartless Kris Allen 95 Here Without You - Alex M. & Marc Van Damme 3:26 Remix Edit Andrew Spencer 142 4:13 Let Her Go Passenger 75 2:28 I Will Survive Me First and the Gimme Gimmes 121 3:23 Baby Don't Lie Gwen Stefani 100 3:50 FU Miley Cyrus 190 5:12 I'd Do Anything For Love (But I Won't Do That) D.J. -

The KARAOKE Channel Song List

11/17/2016 The KARAOKE Channel Song list Print this List ... The KARAOKE Channel Song list Show: All Genres, All Languages, All Eras Sort By: Alphabet Song Title In The Style Of Genre Year Language Dur. 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's Pop 2008 English 3:14 R&B/Hip- 1, 2 Step (Duet) Ciara feat. Missy Elliott 2004 English 3:23 Hop #1 Crush Garbage Rock 1997 English 4:46 R&B/Hip- #1 (Radio Version) Nelly 2001 English 4:09 Hop 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind Rock 2000 English 3:07 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Country 1986 English 4:00 R&B/Hip- 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1994 English 3:09 Hop 100 Years Five for Fighting Pop 2004 English 3:58 11 Cassadee Pope Country 2013 English 3:48 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan Pop 1988 English 4:20 1500 Miles Éric Lapointe Rock 2008 French 3:20 16th Avenue Lacy J. Dalton Country 1982 English 3:16 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed Country 2002 English 5:16 18 And Life Skid Row Rock 1989 English 3:47 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin Pop 1963 English 2:13 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Country 2003 English 3:14 1969 Keith Stegall Country 1996 English 3:22 1982 Randy Travis Country 1986 English 2:56 1985 Bowling for Soup Rock 2004 English 3:15 1999 The Wilkinsons Country 2000 English 3:25 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Pop 2007 English 2:51 R&B/Hip- 21 Questions 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg 2003 English 3:54 Hop 22 Taylor Swift Pop 2013 English 3:47 23 décembre Beau Dommage Holiday 1974 French 2:14 Mike WiLL Made-It feat. -

Jukebox Jade's Song List

JUKEBOX JADE’S SONG LIST BY DECADE 2010s If I Die Young – The Band Perry A Thousand Years – Christina Perri Jar Of Hearts – Christina Perri Afire Love – Ed Sheeran Last Friday Night – Katy Perry All For Love – Bryan Adams Lazy Song – Bruno Mars All I Ask – Adele Let It Go – Frozen All of Me – John Legend Locked Out Of Heaven – Bruno Mars Born This Way – Lady Gaga Love On Top – Beyonce Chandelier – Sia Marry You – Bruno Mars Diamonds – Rihanna Mean – Taylor Swift Die Young – Kesha Moves Like Jagger – Maroon 5 Do You Want To Build A Snowman? – Frozen Only Girl in the World – Rhianna Don’t You Worry Child – Swedish House Mafia Perfect – Ed Sheeran Elastic Heart – Sia Price Tag – Jessie J Empire State of Mind – Alicia Keys Rolling in the Deep – Adele Everglow – Coldplay Safe & Sound – Taylor Swift Firework – Katy Perry Set Fire to the Rain – Adele Forget You – Cee Lo Green Settle Down – Kimbra Girl On Fire – Alicia Keys Skinny Love – Birdy Grenade – Bruno Mars Skyfall – Adele Happy – Pharrell Williams Somebody That I Used to Know – Gotye He Won’t Go – Adele Someone Like You – Adele Hello – Adele Superficial Love – Ruth B Ho Hey! – The Lumineers The Parting Glass – Ed Sheeran Home and Away Theme – Home and Away The One That Got Away – Katy Perry How Far I’ll Go – Moana Thinking Out Loud – Ed Sheeran I’m Not the Only One – Sam Smith Titanium – Sia BY DECADE: PAGE 2 OF 22 2010s (CONTINUED) Breathless – Corinne Bailey Rae Too Good at Goodbyes – Sam Smith Bring Me to Life – Evanescence Try – Pink Bubbly – Colbie Caillat Uptown Funk – Mark Ronson -

Songs by Artist

Andromeda II DJ Entertainment Songs by Artist www.adj2.com Title Title Title 10,000 Maniacs 50 Cent AC DC Because The Night Disco Inferno Stiff Upper Lip Trouble Me Just A Lil Bit You Shook Me All Night Long 10Cc P.I.M.P. Ace Of Base I'm Not In Love Straight To The Bank All That She Wants 112 50 Cent & Eminen Beautiful Life Dance With Me Patiently Waiting Cruel Summer 112 & Ludacris 50 Cent & The Game Don't Turn Around Hot & Wet Hate It Or Love It Living In Danger 112 & Supercat 50 Cent Feat. Eminem And Adam Levine Sign, The Na Na Na My Life (Clean) Adam Gregory 1975 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg And Young Crazy Days City Jeezy Adam Lambert Love Me Major Distribution (Clean) Never Close Our Eyes Robbers 69 Boyz Adam Levine The Sound Tootsee Roll Lost Stars UGH 702 Adam Sandler 2 Pac Where My Girls At What The Hell Happened To Me California Love 8 Ball & MJG Adams Family 2 Unlimited You Don't Want Drama The Addams Family Theme Song No Limits 98 Degrees Addams Family 20 Fingers Because Of You The Addams Family Theme Short Dick Man Give Me Just One Night Adele 21 Savage Hardest Thing Chasing Pavements Bank Account I Do Cherish You Cold Shoulder 3 Degrees, The My Everything Hello Woman In Love A Chorus Line Make You Feel My Love 3 Doors Down What I Did For Love One And Only Here Without You a ha Promise This Its Not My Time Take On Me Rolling In The Deep Kryptonite A Taste Of Honey Rumour Has It Loser Boogie Oogie Oogie Set Fire To The Rain 30 Seconds To Mars Sukiyaki Skyfall Kill, The (Bury Me) Aah Someone Like You Kings & Queens Kho Meh Terri -

U2 All Along the Watchtower U2 All Because of You U2 All I Want Is You U2 Angel of Harlem U2 Bad U2 Beautiful Day U2 Desire U2 D

U/z U2 All Along The Watchtower U2 All Because of You U2 All I Want Is You U2 Angel Of Harlem U2 Bad U2 Beautiful Day U2 Desire U2 Discotheque U2 Electrical Storm U2 Elevation U2 Even Better Than The Real Thing U2 Fly U2 Ground Beneath Her Feet U2 Hands That Built America U2 Haven't Found What I'm Looking For U2 Helter Skelter U2 Hold Me, Thrill Me, Kiss Me, Kill Me U2 I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For U2 I Will Follow U2 In A Little While U2 In Gods Country U2 Last Night On Earth U2 Lemon U2 Mothers Of The Disappeared U2 Mysterious Ways U2 New Year's Day U2 One U2 Please U2 Pride U2 Pride In The Name Of Love U2 Sometimes You Can't Make it on Your Own U2 Staring At The Sun U2 Stay U2 Stay Forever Close U2 Stuck In A Moment U2 Sunday Bloody Sunday U2 Sweetest Thing U2 Unforgettable Fire U2 Vertigo U2 Walk On U2 When Love Comes To Town U2 Where The Streets Have No Name U2 Who's Gonna Ride Your Wild Horses U2 Wild Honey U2 With Or Without You UB40 Breakfast In Bed UB40 Can't Help Falling In Love UB40 Cherry Oh Baby UB40 Cherry Oh Baby UB40 Come Back Darling UB40 Don't Break My Heart UB40 Don't Break My Heart UB40 Earth Dies Screaming UB40 Food For Thought UB40 Here I Am (Come And Take Me) UB40 Higher Ground UB40 Homely Girl UB40 I Got You Babe UB40 If It Happens Again UB40 I'll Be Yours Tonight UB40 King UB40 Kingston Town UB40 Light My Fire UB40 Many Rivers To Cross UB40 One In Ten UB40 Rat In Mi Kitchen UB40 Red Red Wine UB40 Sing Our Own Song UB40 Swing Low Sweet Chariot UB40 Tell Me Is It True UB40 Train Is Coming UB40 Until -

Corinne Gooden Songlist

#41 - Dave Matthews Band 1, 2, 3, 4 - Plain White Ts 1000 Years - Christina Perri 1234 - Feist 17th Street - Corinne Gooden 867-5309 - Tommy Tutone 99 Red Balloons - Nena ABC - Jackson 5 Add It Up - Violent Femmes Rolling In The Deep - Adele Adventure of A Lifetime - Coldplay Ain't No Mountain High Enough - Marvin Gaye Ain't No Rest For The Wicked - Cage The Elephant Ain't No Sunshine - Bill Withers Ain't Too Proud To Beg - Temptations Ain’t It Fun - Paramore Airplane - Indigo Girls Airplanes - BOB/Paramore Alive - Pearl Jam All About That Bass - Meghan Trainor All For You - Sister Hazel All I Want - Joni Mitchell All I Want - Toad The Wet Sprocket All I Want For Christmas - Mariah Carey All I Want To Do - Sugarland All My Days - Corinne Gooden All My Loving - The Beatles All Of Me - John Legend All The Roots Grow Deeper - David Wilcox All The Small Things - Blink 182 All These Things I've Done - Killers All We Ever Do Is Say Goodbye - John Mayer All You Wanted - Michele Branch Almost Is Never Enough - Ariana Grande Almost Lover - Fine Frenzy Alone - Heart Always Be Your Man - Farewell Milwaukee Amazed - Heartland Amazing Grace - Standard American Girl - Tom Petty American Pie - Don McLean Amie - Pure Prairie League Angel - Sarah McLachlan Angel From Montgomery - Bonnie Raitt Animal - Neon Trees Animals - Maroon 5 Anything At All - Corinne Gooden Anything But Down - Sheryl Crow Are You Gonna Be My Girl - Jet At Last - Etta James Auld Lang Syne - Christmas Autumn Leaves - Standard Avalanche Baby Can I Hold You - Tracy Chapman Baby Girl