Statement of the Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Say Es Say Es

May 2018 A publication of Sexaholics Anonymous featuring: ES Member Stories Shame & the 4th Dimension: Harvey A. Articles Working the Steps: A New Pair of Shoes SAY Staying Sober The Gift of Healing Perils of Breaking Anonymity ANONYMITYANONYMITY Essay presents the experience, strength, and hope of SA members. Essay is aware that every SA member has an individual way of working the program. In submitting articles, please remember SA’s sobriety definition is not debated, since it distinguishes SA from other sex addiction fellowships. Opinions expressed in Essay are not to be attributed to SA as a whole, nor does publication of any article imply endorsement by SA or by Essay. The theme for this issue May 2018 is: Anonymity. Future topics are: Relating With Others- the 12 Traditions in August; Humility in October; As We Understood God and Dealing With Mixed Meetings. Closing date for articles is approximately four weeks prior to publication dates in February, May, August, October, and December. Resolution: “Since each issue of Essay cannot go through the SA Literature approval process, the Trustees and General Delegate Assembly recognize Essay as the International Journal of Sexaholics Anonymous and support the use of Essay materials in SA meetings.” Adopted by the Trustees and Delegate Assembly in May, 2016 Permission to Copy As of June, 2017 the Essay in digital form is available free from the sa.org/essay web site. In order to serve the members of the SA fellowship, a print subscriber or a person using a free download of an Essay issue is granted permission to distribute or make ten copies—print or digital—of that issue, to be shared with members of SA. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Danamare Productions Mobile DJ & Karaoke Karaoke Songbook Sorted by Title

Danamare Productions Mobile DJ & Karaoke Karaoke Songbook Sorted by Artist 1 Artist Title ID 10 Years Beautiful 320 112 Peaches and cream 320 2 Live Crew Me So Horny (PA) 320 3 Doors Down Let Me Go (Rock Version) 320 3 Doors Down Loser 320 3 DOORS DOWN LOSER 320 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 320 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 320 3 Doors Down Kryptonie 320 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 320 38 Special Hold On Loosely 320 42nd STREET LULLABYE OF BROADWAY 320 5 man electric band Signs 320 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 320 5 Seconds Of Summer Amnesia- 5 Seconds Of Summer 320 5 Seconds Of Summer Amnesia- 320 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 320 50 Cent Disco Inferno 320 50 Cent In Da Club 320 98 Degrees The Hardest Thing 320 98 Degrees I Do 320 A-ha Take me on 320 A CHORUS LINE WHAT I DID FOR LOVE 320 A CHORUS LINE NOTHING 320 A Gret Big World & Christina Say Something 320 A3 Woke Up This Morning 320 Aaliyah I Don't Wanna 320 Aalyiah Try Again 320 Aaron Neivelle Tell it like it is 192 Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool 320 Aaron Tippin People Like Us 320 Abba Waterloo 320 Abba Dancing Queen 320 Abba Waterloo 320 AC DC / Stiff Upper Lip 320 AC DC / Highway To Hell 320 AC DC / Whole Lotta Rosie 320 AC DC / Stiff Upper Lip 320 AC-DC You shook me all night long 320 AC DC Big Balls (PA) 320 Danamare Productions Mobile DJ & Karaoke - Karaoke Songbook by Artist 2 Artist Title ID ACDC Back In Black 320 ACDC Hell's Bells 320 ACDC (made famous by ~) (karao Highway to hell 320 Ace Of Base Living In Danger 320 Ace Of Base Sign -- Act Naturally -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Versions Title Artist Versions #1 Crush Garbage SC 1999 Prince PI SC #Selfie Chainsmokers SS 2 Become 1 Spice Girls DK MM SC (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue SF 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue MR (Don't Take Her) She's All I Tracy Byrd MM 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden SF Got 2 Stars Camp Rock DI (I Don't Know Why) But I Clarence Frogman Henry MM 2 Step DJ Unk PH Do 2000 Miles Pretenders, The ZO (I'll Never Be) Maria Sandra SF 21 Guns Green Day QH SF Magdalena 21 Questions (Feat. Nate 50 Cent SC (Take Me Home) Country Toots & The Maytals SC Dogg) Roads 21st Century Breakdown Green Day MR SF (This Ain't) No Thinkin' Trace Adkins MM Thing 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard MR + 1 Martin Solveig SF 21st Century Girl Willow Smith SF '03 Bonnie & Clyde (Feat. Jay-Z SC 22 Lily Allen SF Beyonce) Taylor Swift MR SF ZP 1, 2 Step Ciara BH SC SF SI 23 (Feat. Miley Cyrus, Wiz Mike Will Made-It PH SP Khalifa And Juicy J) 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind SC 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band SG 10 Million People Example SF 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney MM 10 Minutes Until The Utilities UT 24-7 Kevon Edmonds SC Karaoke Starts (5 Min 24K Magic Bruno Mars MR SF Track) 24's Richgirl & Bun B PH 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan PH 25 Miles Edwin Starr SC 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys BS 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash SF 100 Percent Cowboy Jason Meadows PH 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago BS PI SC 100 Years Five For Fighting SC 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The MM SC SF 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris SC 26 Miles Four Preps, The SA 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters PI SC 29 Nights Danni Leigh SC 10000 Nights Alphabeat MR SF 29 Palms Robert Plant SC SF 10th Avenue Freeze Out Bruce Springsteen SG 3 Britney Spears CB MR PH 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan BS SC QH SF Len Barry DK 3 AM Matchbox 20 MM SC 1-2-3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Complete Song List

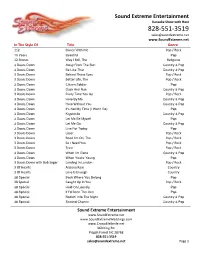

Sound Extreme Entertainment Karaoke Show with Host 828-551-3519 [email protected] www.SoundExtreme.net In The Style Of Title Genre 112 Dance With Me Pop / Rock 10 Years Beautiful Pop 12 Stones Way I Fell, The Religious 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Country & Pop 3 Doors Down Be Like That Country & Pop 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Pop / Rock 3 Doors Down Better Life, The Pop / Rock 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier Pop 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Country & Pop 3 Doors Down Every Time You Go Pop / Rock 3 Doors Down Here By Me Country & Pop 3 Doors Down Here Without You Country & Pop 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) Pop 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Country & Pop 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself Pop 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Country & Pop 3 Doors Down Live For Today Pop 3 Doors Down Loser Pop / Rock 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The Pop / Rock 3 Doors Down So I Need You Pop / Rock 3 Doors Down Train Pop / Rock 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Country & Pop 3 Doors Down When You're Young Pop 3 Doors Down with Bob Seger Landing In London Pop / Rock 3 Of Hearts Arizona Rain Country 3 Of Hearts Love Is Enough Country 38 Special Back Where You Belong Pop 38 Special Caught Up In You Pop / Rock 38 Special Hold On Loosely Pop 38 Special If I'd Been The One Pop 38 Special Rockin' Into The Night Country & Pop 38 Special Second Chance Country & Pop Sound Extreme Entertainment www.SoundExtreme.net www.SoundExtremeWeddings.com www.CrocodileSmile.net 360 King Rd. -

A Tribute to Cal Howard, S'54

Sigma Phi Never Forget Never Forget Never ForgetFLAMENever Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget NUMBER 112 • DECEMBER 2008 Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never F Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never F Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never F Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget A Tribute to Cal Howard, S’54 1934 - 2008 Also Inside: Wisconsin Centennial Convention Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never Forget Never F PAGE 2 THE FLAME The Chairman’s Message: “An Old Pair of Shoes” by Marshall Solem, F’79 [email protected] lose your eyes for a minute and Society would have withered on the vine think back to your days on cam- decades ago. C pus. More specifically, consider The easy truth is that we all know your days at the Sigma Phi Place. Think the impact involved alumni can have. back to the Sig alumni who influenced The hard truth is that Sigma Phi needs your undergraduate experience. still more alumni participation – today, Perhaps it was the brother who tomorrow, and every day. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title Title +44 3 Doors Down 5 Stairsteps, The When Your Heart Stops Live For Today Ooh Child Beating Loser 50 Cent 10 Years Road I'm On, The Candy Shop Beautiful When I'm Gone Disco Inferno Through The Iris When You're Young In Da Club Wasteland 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Just A Lil' Bit 10,000 Maniacs Landing In London P.I.M.P. (Remix) Because The Night 3 Of Hearts Piggy Bank Candy Everybody Wants Arizona Rain Window Shopper Like The Weather Love Is Enough 50 Cent & Eminem & Adam Levine These Are Days 30 Seconds To Mars My Life 10CC Closer To The Edge My Life (Clean Version) Dreadlock Holiday Kill, The 50 Cent & Mobb Deep I'm Not In Love 311 Outta Control 112 Amber 50 Cent & Nate Dogg Peaches & Cream Beyond The Gray Sky 21 Questions U Already Know Creatures (For A While) 50 Cent & Ne-Yo 1910 Fruitgum Co. Don't Tread On Me Baby By Me Simon Says Hey You 50 Cent & Olivia 1975, The I'll Be Here Awhile Best Friend Chocolate Lovesong 50 Cent & Snoop Dogg & Young 2 Pac You Wouldn't Believe Jeezy California Love 38 Special Major Distribution (Clean Changes Hold On Loosely Version) Dear Mama Second Chance 5th Dimension, The How Do You Want It 3LW Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) 2 Pistols & Ray J No More Aquariuslet The Sunshine You Know Me 3OH!3 In 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Trust Me Last Night I Didn't Get To She Got It StarStrukk Sleep At All 21 Demands 3OH!3 & Ke$ha One Less Bell To Answer Give Me A Minute My First Kiss Stoned Soul Picnic 3 Doors Down 3OH!3 & Neon Hitch Up Up & Away Away From The Sun Follow Me Down Wedding Bell Blues Be Like That 3T 6 Tre G Behind Those Eyes Anything Fresh Citizen Soldier 4 Non Blondes 702 Duck & Run What's Up I Still Love You Here By Me 4 P.M. -

Karaoke Songbook

Karaoke Songbook 10,000 Maniacs 5 Seconds of Summer A Taste of Honey (cont.) Candy Everybody Wants Amnesia We Are Never Ever Getting Back 10Cc Don't Stop Together Dreadlock Holiday Good Girls A Teens I'm Not In Love She Looks So Perfect Bouncing Off The Ceiling Things We Do For Love, The 50 Cent Halfway Around The World 112 21 Questions A-Ha Dance With Me Candy Shop Analogue 19 2000 In Da Club Cry Wolf Gorillaz Just A Lil Bit Aaliyah 1910 Fruitgum Co. 50-Cent Feat. Eminem and Adam I Don't Wanna Simon Says Levine Miss You 2 Unlimited My Life (Clean) More Than A Woman No Limit 5Th Dimension Rock The Boat 3 Doors Down Aquarius Try Again Away From The Sun Go Where You Wanna Go Aaliyah & Tank Be Like That I Didn't Get To Sleep At All, (Last Come Over Behind Those Eyes Nigh Aaliyah Feat Timbaland Citizen Soldier Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At We Need A Resolution Every Time You Go All Aaron Neville & Linda Ronstadt Here By Me Never My Love Don't Know Much Here Without You One Less Bell To Answer Aaronson, Irving & The It's Not My Time Stoned Soul Picnic Commanders Kryptonite Up Up and Away Let's Misbehave Let Me Be Myself Wedding Bell Blues Abba Let Me Go Davis, Billy Jr. & Marilyn Mccoo As Good As New Live For Today You Don't Have To Be A Star Chiquita Loser 98 Degrees Dancing Queen When I'm Gone Because of You Day Before You Came When You're Young Give Me Just One Night (Una Does Your Mother Know 30 Seconds To Mars Noche) Fernando Kings and Queens Hardest Thing, The Gimme Gimme Gimme 311 I Do (Cherish You) Happy New Year All Mixed Up This Gift Hasta Manana 38 Special A Great Big World With Christina Have A Dream Hold On Loosely A. -

The O'jays to Reba Mcentire

Sound Extreme Entertainment Karaoke Show with Host 828-551-3519 [email protected] www.SoundExtreme.net In The Style Of Title Genre O'Jays, The I Love Music Oldies O'Jays, The Livin' For The Weekend Pop / Rock O'Jays, The Love Train Country & Pop O'Jays, The Use Ta Be My Girl Pop O'Jays. The I Love America Oldies OK Go Here It Goes Again Pop O'Kaysions, The Girl Watcher Country & Pop Olivia Newton-John Have You Never Been Mellow Country & Pop Olivia Newton-John I Honestly Love You Country & Pop Olivia Newton-John Let Me Be There Country & Pop Olivia Newton-John Magic Country & Pop Olivia Newton-John Physical Country & Pop Olivia Newton-John & Cliff Richard Suddenly Country & Pop Olivia Newton-John & John Travolta Summer Nights Country & Pop Olivia Newton-John & John Travolta You're The One That I Want Pop / Rock Ollie And Jerry Breakin'...There's No Stopping Us Pop Omarion Speedin' Pop One Flew South My Kind Of Beautiful Country OneRepublic All The Right Moves Pop OneRepublic Secrets Pop Orianthi According To You Pop Orianthi Shut Up And Kiss Me Pop Osborne Brothers & Red Allen, The Ruby, Are You Mad Bluegrass Osborne Brothers, The Cuckoo, The Bluegrass Osborne Brothers, The I'll Be Alright Tomorrow Bluegrass Osborne Brothers, The Lost Highway Country Osborne Brothers, The Rocky Top Country & Pop Osborne Brothers, The Roll Muddy River Country & Pop Oscar McLollie And His Honey Jumpers Dig That Crazy Santa Claus Christmas Sound Extreme Entertainment www.SoundExtreme.net www.SoundExtremeWeddings.com www.CrocodileSmile.net 360 King Rd. -

Disk Catalog by Category

COUNTRY: 70's 80's - KaraokeStar.com 800-386-5743 or 602-569-7827 COUNTRY: 70's & 80's COUNTRY: 70's & 80's COUNTRY: 70's & 80's COUNTRY: 70's & 80's Luckenbach Texas Jennings, Waylon Happiest Girl In The Whole USA Fargo, Donna Vocal Guides: No Vocal Guides: Yes BL33 Lyric Sheet: No Funny Face Fargo, Donna CB20513 Lyric Sheet: No Vocal Guides: Yes Superman Fargo, Donna Legends Bassline KaraokeStar.com CB20328 Lyric Sheet: No Chartbuster 6+6 Country KaraokeStar.com You Were Always There Fargo, Donna Country Classics $19.99 Chartbuster 6+6 Country KaraokeStar.com Hits Of Lefty Frizzell Vol 1 $12.99 You Can't Be A Beacon Fargo, Donna Waylon Jennings Vol 2 $12.99 Hello Mary Lou Nelson, Ricky Little Girl Gone Fargo, Donna Always Late With Your Kisses Frizzell, Lefty Rhinestone Cowboy Campbell, Glen Mamas Don't Let Your Babies GrJennings, Waylon I Love You A Thousand WaysFrizzell, Lefty What I've Got In Mind Spears, Billie Jo I've Always Been Crazy Jennings, Waylon Vocal Guides: Yes I Overlooked An Orchid Frizzell, Lefty CB20502 No Your Cheating Heart Williams, Hank Good Ol Boys Jennings, Waylon Lyric Sheet: If You've Got The Money I've Got Frizzell, Lefty KaraokeStar.com If I Said You Had A Beautiful BoBellamy Brothers Lucille Jennings, Waylon Chartbuster 6+6 Country Mom And Dad's Waltz Frizzell, Lefty Forester Sisters Vol 1 DIVORCE Wynette, Tammy Wrong Jennings, Waylon $12.99 Saginaw Michigan Frizzell, Lefty Harper Valley PTA Riley, Jeannie C Lovin Her Was Easier Jennings, Waylon Men Forester Sisters Vocal Guides: Yes Mississipi Pussy Cat -

Songs by Artist

Chansons en anglais - Songs in English ARTIST / ARTISTE TITLE / TITRE ARTIST / ARTISTE TITLE / TITRE 10 Years Through The Iris 21 Demands Give Me A Minute Wasteland 2Unlimited No Limit 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun More Than This Be Like That These Are The Days Duck And Run Trouble Me Every Time You Go 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody'S Been Sleepin Here By Me 101 Dalmations Cruella De Vil Here Without You 10Cc Donna It'S Not My Time Dreadlock Holiday Krypnotite I'M Not In Love Landing In London Rubber Bullets Let Me Be Myself The Things We Do For Let Me Go Love Live For Today The Wall Street Shuffle Loser 112 Come See Me Road I'M On Dance With Me The Road I'M On It'S Over Now Train Only You When I'M Gone Peaches And Cream 3 Of Hearts Arizona Rain 12 Stones We Are One Love Is Enough 1910 Fruit Gum Co. 1,2,3 Red Light 30 Seconds To Mars The Bury Me Kill Simon Says The Kill 2 Live Crew Doo Wah Diddy 30H!3 & Katy Perry Starstrukk Me So Horny 30H!3 And Katy Perry Starstrukk We Want Some Pussy 311 All Mixed Up 2 Pac Changes Down Thugz Mansion I'Ll Be Here Awhile Until The End Of Time You Wouldn'T Believe 2 Pac & Eminem One Day At A Time 38 Special Caught Up In You 2 Pistols And Ray J You Know Me Hold On Loosely 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If I'D Been The One Page 1 of/de 329 Chansons en anglais - Songs in English ARTIST / ARTISTE TITLE / TITRE ARTIST / ARTISTE TITLE / TITRE 38 Special Rockin' Into The Night 50 Cent And Ayo Technology Timberlake Second Chance 50 Cent Feat.Ne-Yo Baby By Me Wildeyed Southern Boys,