Puppet Knowledge and the Life of the Puppeteer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marlboro College

Potash Hill Marlboro College | Spring 2020 POTASH HILL ABOUT MARLBORO COLLEGE Published twice every year, Marlboro College provides independent thinkers with exceptional Potash Hill shares highlights of what Marlboro College community opportunities to broaden their intellectual horizons, benefit from members, in both undergraduate a small and close-knit learning community, establish a strong and graduate programs, are doing, foundation for personal and career fulfillment, and make a positive creating, and thinking. The publication difference in the world. At our campus in the town of Marlboro, is named after the hill in Marlboro, Vermont, where the college was Vermont, students engage in deep exploration of their interests— founded in 1946. “Potash,” or potassium and discover new avenues for using their skills to improve their carbonate, was a locally important lives and benefit others—in an atmosphere that emphasizes industry in the 18th and 19th centuries, critical and creative thinking, independence, an egalitarian spirit, obtained by leaching wood ash and evaporating the result in large iron and community. pots. Students and faculty at Marlboro no longer make potash, but they are very industrious in their own way, as this publication amply demonstrates. Photo by Emily Weatherill ’21 EDITOR: Philip Johansson ALUMNI DIRECTOR: Maia Segura ’91 CLEAR WRITING STAFF PHOTOGRAPHERS: To Burn Through Where You Are Not Yet BY SOPHIE CABOT BLACK ‘80 Emily Weatherill ’21 and Clement Goodman ’22 Those who take on risk are not those Click above the dial, the deal STAFF WRITER: Sativa Leonard ’23 Who bear it. The sign said to profit Downriver is how you will get paid, DESIGN: Falyn Arakelian Potash Hill welcomes letters to the As they do, trade around the one Later, further. -

Puppetry Beyond Entertainment, How Puppets Are Used Politically to Aid Society

PUPPETRY BEYOND ENTERTAINMENT, HOW PUPPETS ARE USED POLITICALLY TO AID SOCIETY By Emily Soord This research project is submitted to the Royal Welsh College of Music & Drama, Cardiff, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Theatre Design April 2008 i Declaration I declare that this Research Project is the result of my own efforts. The various sources to which I am indebted are clearly indicated in the references in the text or in the bibliography. I further declare that this work has never been accepted in the substance of any degree, and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any other degree. Name: (Candidate) Name: (Supervisor) ii Acknowledgements Many people have helped and inspired me in writing this dissertation and I would like to acknowledge them. My thanks‟ to Tina Reeves, who suggested „puppetry‟ as a subject to research. Writing this dissertation has opened my eyes to an extraordinary medium and through researching the subject I have met some extraordinary people. I am grateful to everyone who has taken the time to fill out a survey or questionnaire, your feedback has been invaluable. My thanks‟ to Jill Salen, for her continual support, inspiration, reassurance and words of advice. My gratitude to friends and family for reading and re-reading my work, for keeping me company seeing numerous shows, for sharing their experiences of puppetry and for such interesting discussions on the subject. Also a big thank you to my dad and my brother, they are both technological experts! iii Abstract Puppets are extraordinary. -

Translating Expertise Across Work Contexts: U.S. Puppeteers Move

ASRXXX10.1177/0003122420987199American Sociological ReviewAnteby and Holm 987199research-article2021 American Sociological Review 2021, Vol. 86(2) 310 –340 Translating Expertise across © American Sociological Association 2021 https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122420987199DOI: 10.1177/0003122420987199 Work Contexts: U.S. Puppeteers journals.sagepub.com/home/asr Move from Stage to Screen Michel Antebya and Audrey L. Holma Abstract Expertise is a key currency in today’s knowledge economy. Yet as experts increasingly move across work contexts, how expertise translates across contexts is less well understood. Here, we examine how a shift in context—which reorders the relative attention experts pay to distinct types of audiences—redefines what it means to be an expert. Our study’s setting is an established expertise in the creative industry: puppet manipulation. Through an examination of U.S. puppeteers’ move from stage to screen (i.e., film and television), we show that, although the two settings call on mostly similar techniques, puppeteers on stage ground their claims to expertise in a dialogue with spectators and view expertise as achieving believability; by contrast, puppeteers on screen invoke the need to deliver on cue when dealing with producers, directors, and co-workers and view expertise as achieving task mastery. When moving between stage and screen, puppeteers therefore prioritize the needs of certain audiences over others’ and gradually reshape their own views of expertise. Our findings embed the nature of expertise in experts’ ordering of types of audiences to attend to and provide insights for explaining how expertise can shift and become co-opted by workplaces. Keywords expertise, audiences, puppetry, film and television Expertise has become a fundamental currency of cases (Abbott 1988:8). -

Stories and Storytelling - Added Value in Cultural Tourism

Stories and storytelling - added value in cultural tourism Introduction It is in the nature of tourism to integrate the natural, cultural and human environment, and in addition to acknowledging traditional elements, tourism needs to promote identity, culture and interests of local communities – this ought to be in the very spotlight of tourism related strategy. Tourism should rely on various possibilities of local economy, and it should be integrated into local economy structure so that various options in tourism should contribute to the quality of people's lives, and in regards to socio-cultural identity it ought to have a positive effect. Proper treatment of identity and tradition surely strengthen the ability to cope with the challenges of world economic growth and globalisation. In any case, being what you are means being part of others at the same time. We enrich others by what we bring with us from our homes. (Vlahović 2006:310) Therefore it is a necessity to develop the sense of culture as a foundation of common identity and recognisability to the outer world, and as a meeting place of differences. Subsequently, it is precisely the creative imagination as a creative code of traditional heritage through intertwinement and space of flow, which can be achieved solely in a positive surrounding, that presents the added value in tourism. Only in a happy environment can we create sustainable tourism with the help of creative energy which will set in motion our personal aspirations, spread inspiration and awake awareness with the strength of imagination. Change is possible only if it springs from individual consciousness – „We need a new way to be happy” (Laszlo, 2009.). -

The Jim Henson Company Honors Founder Jim Henson's 85Th Birthday

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Nicole Goldman [email protected] The Jim Henson Company Honors Founder Jim Henson’s 85th Birthday Company Offers Fun Ways to Celebrate Throughout the Month of September Hollywood, CA (September 7, 2021) – This September, fans around the world, and across social media, will honor the 85th birthday of innovative and inspiring puppeteer, director, and producer Jim Henson (b.9/24/1936). Founded by Jim and Jane Henson in 1955, The Jim Henson Company, continuing its legacy with projects like The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance, Dinosaur Train, Word Party, and the upcoming Fraggle Rock reboot, is sharing lots of ways to celebrate through partnerships and social media (#JimHensonBirthday). • NOOK by Barnes & Noble Features an eBook for Everyone Barnes & Noble is offering a wide collection of eBooks like Jim Henson’s classic Fraggle Rock, as well as contemporary titles including Dinosaur Train, Word Party, Sid the Science Kid, and many more through its Free NOOK Reading Apps (iOS and Android) and NOOK Tablets. Preorder now and save with special limited-time only pricing. Visit here to start exploring. • Sony and Fathom Events Welcome Fans to Labyrinth Sony has released a new 4K Ultra HD limited edition of Jim Henson’s fantasy classic Labyrinth, featuring extras including audition footage for the role of Sarah, and never before seen deleted & alternate scenes. Fathom Events is celebrating the 35th anniversary of the film and Henson’s birthday with in-theater screenings on September 12, 13 and 15th. Get your tickets here. Order your collectible 4K Ultra HD here. • Fraggle Rock partners with Waze Your commute in Outer Space is an amazing adventure when Red is your co-pilot on Waze! Silly Creatures will be able to customize their vehicles to look like Doozer trucks and hear Red Fraggle give directions during their journey. -

Stuy Hall to Begin Multi-Million Renovation Ohio Wesleyan Honors Memory of Alice Klund Levy, ‘32, Who Endowed $1 Million to University in Estate Gift

A TRUE COLLEGE NEWSPAPER TranscripTHE T SINCE 1867 Thursday, Oct. 29, 2009 Volume 148, No. 7 Stuy Hall to begin multi-million renovation Ohio Wesleyan honors memory of Alice Klund Levy, ‘32, who endowed $1 million to university in estate gift Phillips Hall vandalized By Michael DiBiasio Editor-in-Chief Graffiti was found inside and outside Phillips Hall Monday morning by an Ohio Wesleyan house- keeper with no sign of Photos provided courtesy of.... forced entry to the building, Left: Stuyvesant Hall shortly after it opened in 1931. Note the according to Public Safety. statue above the still-working white fountain. Public Safety Sergeant Above: Alice Klund Levy, pictured in this field hockey team photo in Christopher Mickens said the front row second from left, left a $1 million donation after her he is unsure whether the death in 2008, to be used for Stuy’s renovation. This will account markings found on chalk- for a considerable chunk of the planned restoration. boards, whiteboards, refrigerators and doors in By Mary Slebodnik have to use the money for a majored in politics and gov- ing her president of Mortar days and date nights because Phillips have any specific Transcript Reporter predetermined project or spe- ernment and French. She Board. normal heels echoed too loud- meaning. cific department. That deci- played field hockey along- According the 1932 edi- ly in the hallways. “Generally, such sym- A late alumna’s $1 million sion was left up to administra- side Helen Crider, whom the tion of “Le Bijou,” the cam- On Oct. 3-4, the board of bols represent the name of gift to the university might tors. -

Center for Puppetry Arts Unveils Plans for Dramatic Expansion Project Project Highlights Include New Museum, Featuring World's

FOR MORE INFORMATION: Jennifer Walker BRAVE Public Relations, 404.233.3993 [email protected] Center for Puppetry Arts Unveils Plans for Dramatic Expansion Project Project highlights include new museum, featuring world’s largest collection of Jim Henson puppets and artifacts. ATLANTA (January 14, 2014) – Center for Puppetry Arts officials announced today details on the organization’s highly anticipated renovation and expansion plans. The project, set to be completed in 2015, will include a new museum, with a Global Collection and the world’s most comprehensive collection of Jim Henson’s puppets and artifacts. Project highlights also include a new library and archival space, a renovated entryway and many other upgrades to existing spaces that will ultimately enhance the experience for Center for Puppetry Arts’ visitors. As the nation’s largest nonprofit dedicated to the art of puppetry, these updates will allow the organization to continue to touch even more lives through the art of puppetry while giving guests a new appreciation for the global scope and universal power of the art form. As part of the project, the Center is protecting and preserving hundreds of international and Henson treasures for future generations to explore and understand. In 2007, Jim Henson’s family announced a momentous gift of puppets and props to the Center for Puppetry Arts. Approximately half of the expanded museum space will be dedicated to the Jim Henson Collection, which will feature recognizable puppets from Sesame Street, The Muppet Show, Fraggle Rock, The Dark Crystal and Emmet Otter’s Jug-Band Christmas. Featured icons will include Miss Piggy, Kermit the Frog, Fozzie Bear, Big Bird, Elmo, Grover, Bert, Ernie and many more. -

TÍTERES EN PUERTO RICO, UNA PERPETUA Y ACOMPASADA EVOLUCIÓN Indice SEPTIEMBRE - DICIEMBRE / 2018

la hoja del titiritero / SEPTIEMBRE - DICIEMBRE / 2018 1 BOLETÍN ELECTRÓNICO DE LA COMISIÓN UNIMA 3 AMÉRICAS TERCERA ÉPOCA SEPTIEMBRE - DICIEMBRE03 / 2018 TÍTERES EN PUERTO RICO, UNA PERPETUA Y ACOMPASADA EVOLUCIÓN indIce SEPTIEMBRE - DICIEMBRE / 2018 ENCABEZADO DE BUENA FUENTE: 03 · Pinceladas puertorriqueñas Influencias de otros lares en la isla Dr. Manuel Antonio Morán 25 · Kamishibai-Puerto Rico Tere Marichal l boletín electrónico La Hoja LETRA CAPITAL del Titiritero, de la Comisión 04 · Las voces titiriteras de Suramérica Personalidades y agrupaciones del Unima 3 Américas, sale teatro de figuras en Puerto Rico con frecuencia cuatrienal, EN GRAN FORMATO · El Mundo de los Muñecos: con cierre los días 15 de · Breve panorama del teatro de títeres 28 40 años de alegría Eabril, agosto y diciembre. Las 07 en Puerto Rico 30 · Un titiritero llamado Mario Donate normas editoriales, teniendo en Dr. Manuel Antonio Morán cuenta el formato de boletín, son De festivales y publicaciones titiriteras de una hoja para las noticias e CUADRO DE TEXTOS en Puerto Rico informaciones, dos hojas para las entrevistas y tres hojas para los · Las huellas de la tempestad en el · Sobre la mesa. Una asignación (Acerca 11 31 artículos de fondo, investigaciones Corazón de Papel de Agua, Sol y Sereno del fenómeno de títeres para adultos en o reseñas críticas. De ser posible Cristina Vives Rodríguez Puerto Rico). Deborah Hunt acompañar los materiales con · Y No Había Luz antes 33 · La Titeretada: un festival independiente 14 imágenes. y después de María 34 · Otros festivales titiriteros · Papel Machete: el teatro de títeres y la · Algunas publicaciones de títeres en 16 Director lucha popular en Puerto Rico Puerto Rico Dr. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Kevin Clash

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Kevin Clash Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Clash, Kevin Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Kevin Clash, Dates: September 21, 2007 Bulk Dates: 2007 Physical 6 Betacame SP videocasettes (2:37:58). Description: Abstract: Puppeteer Kevin Clash (1960 - ) created the character Elmo on Sesame Street. A multiple Emmy Award-winning puppeteer, he also performed on the television programs, Captain Kangaroo, and Dinosaurs, and in the films, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and Muppet Treasure Island. Clash was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on September 21, 2007, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2007_268 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Children’s educational puppeteer Kevin Clash was born on September 17, 1960 in Turner’s Station, a predominantly black neighborhood in the Baltimore, Maryland suburb of Dundalk, to George and Gladys Clash. In 1971, at the age of ten, Clash began building puppets, after being inspired by the work of puppeteers on the Sesame Street television program, a passion that stuck with him throughout his teen years. His first work on television was for WMAR, a CBS affiliate that produced a show entitled Caboose. Clash also performed a pelican puppet character for the WTOP- TV television program Zep. In his late teens, Clash met Kermit Love, a puppet designer for the Muppets, who arranged for Clash to observe the Sesame Street set. -

Teacher's Resource

TEACHER’S RESOURCE Produced by the Education Department UBC Museum of Anthropology 6393 NW Marine Dr. Vancouver BC, V6T 1Z2 www.moa.ubc.ca [email protected] 2020 Learning Through Puppetry + Play ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS Teaching Kit Overview ....................................................................................v Chapter 1 Puppets: An Introduction .............................................................1 In the Teacher’s Resource ............................................................................... 1 In the Kit ......................................................................................................... 1 Stories ............................................................................................................ 2 Making + Performing Puppets ......................................................................... 2 Chapter 2 Bringing Puppets to Life ..............................................................5 Tips for New Puppeteers ................................................................................. 5 Chapter 3 Class Activities ............................................................................9 Puppet Cards ................................................................................................ 10 Care + Handling ............................................................................................ 10 Meet the Puppets .......................................................................................... 11 BIG IDEAS • Puppetry is shared -

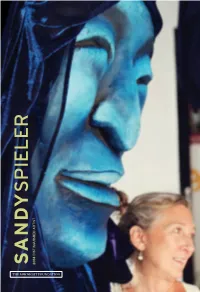

S and Y Spieler

SANDYSPIELER 2014 DISTINGUISHED ARTIST She changes form. She moves in between things and in between states, from liquid to solid to vapor: raindrop, snowflake, cloud. She orients. She refreshes. She transforms and sculpts everyone she encounters. She is a landmark and a route to follow. She quenches our thirst. We will not live without the lessons in which she continually involves us any more than we could live without water. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION SHE MOVES LIKE WATER: When a MinnPost interviewer asked Sandy Spieler why she had chosen puppets as her medium, Sandy replied that “ DIVINING SANDY SPIELER HAVE NO PUPPETS COLLEEN SHEEHY 3 LIFE OF THEIR OWN, AND YET, WHEN YOU PICK THEM UP, A BREATH COMES INTO THEM. And then, when you lay them down, the breath goes THEATER OF HOPE out. It’s the ritual of life: We’re brought to our birth, then we move in our DAVID O’FALLON 18 life, then we lie down to the earth again.” For Sandy, such transformation is the very essence of art, and the transformation IN THE HEART OF THE CITY in which she specializes extends far beyond any single performance. She and her HARVEY M. WINJE 21 colleagues and her neighbors transform ideas into spectacle. They transform everyday materials like cardboard, sticks, fabric, and paper into figures that come to life. And through their art, Sandy and her collaborators at In the Heart of the Beast Puppet BIGGER THAN OURSELVES and Mask Theatre (HOBT) have helped transform their city and our region. Their PAM COSTAIN 25 work—which invites people in by traveling to where they live, learn, play, and work— combines arresting visuals, movement, and music to inspire us to be the caretakers of our communities and the earth. -

Filippino Lippi and Music

Filippino Lippi and Music Timothy J. McGee Trent University Un examen attentif des illustrations musicales dans deux tableaux de Filippino Lippi nous fait mieux comprendre les intentions du peintre. Dans le « Portrait d’un musicien », l’instrument tenu entre les mains du personnage, tout comme ceux représentés dans l’arrière-plan, renseigne au sujet du type de musique à être interprétée, et contribue ainsi à expliquer la présence de la citation de Pétrarque dans le tableau. Dans la « Madone et l’enfant avec les anges », la découverte d’une citation musicale sur le rouleau tenu par les anges musiciens suggère le propos du tableau. n addition to their value as art, paintings can also be an excellent source of in- Iformation about people, events, and customs of the past. They can supply clear details about matters that are known only vaguely from written accounts, or in some cases, otherwise not known at all. For the field of music history, paintings can be informative about a number of social practices surrounding the performance of music, such as where performances took place, who attended, who performed, and what were the usual combinations of voices and instruments—the kind of detail that is important for an understanding of the place of music in a society, but that is rarely mentioned in the written accounts. Paintings are a valuable source of information concerning details such as shape, exact number of strings, performing posture, and the like, especially when the painter was knowledgeable about instruments and performance practices,