China's Stealthy Sovereignty: the Importance of Objective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Release

Media Release Another record breaking year for Changi Airport Annual passenger traffic crosses 45-million mark for first time in 2011 SINGAPORE, 20 January 2012 – Singapore Changi Airport registered a strong performance last month to achieve new records for passenger traffic and aircraft movements in 2011. Celebrating its 30 th anniversary in 2011, Changi Airport managed 46.5 million passenger movements and 302,000 aircraft movements during the year, an increase of 10.7% and 14.5% respectively. Airfreight movements recovered to 2008 levels with 1.87 million tonnes of cargo handled, up 2.8% from 2010. December 2011 was Changi Airport’s busiest month ever with 4.53 million passenger movements, 11.4% more than a year ago. Changi’s daily record was also broken on 17 December 2011 with 165,000 passengers passing through during the 24 hours, surpassing the previous record of 148,000 passengers on 19 June 2011. There were 27,700 aircraft movements last month, an increase of 16.0% compared to December 2010. As at 1 January 2012, Changi Airport handles more than 6,300 scheduled flights each week, an increase of 16.7% from a year ago. More than 100 airlines now connect Singapore to 210 cities in 60 countries globally. In terms of cargo movements, steady demand for airfreight enabled Changi Airport to close the year on a positive note. Some 167,000 tonnes of cargo were handled in December, an increase of 6.9% on-year, representing Changi’s busiest month in three years. In 2011, Changi’s cargo community welcomed the launch of freighter flights to Chengdu and Chongqing in China, and the introduction of all-freighter flights by Emirates and Lufthansa Cargo. -

08-06-2021 Airline Ticket Matrix (Doc 141)

Airline Ticket Matrix 1 Supports 1 Supports Supports Supports 1 Supports 1 Supports 2 Accepts IAR IAR IAR ET IAR EMD Airline Name IAR EMD IAR EMD Automated ET ET Cancel Cancel Code Void? Refund? MCOs? Numeric Void? Refund? Refund? Refund? AccesRail 450 9B Y Y N N N N Advanced Air 360 AN N N N N N N Aegean Airlines 390 A3 Y Y Y N N N N Aer Lingus 053 EI Y Y N N N N Aeroflot Russian Airlines 555 SU Y Y Y N N N N Aerolineas Argentinas 044 AR Y Y N N N N N Aeromar 942 VW Y Y N N N N Aeromexico 139 AM Y Y N N N N Africa World Airlines 394 AW N N N N N N Air Algerie 124 AH Y Y N N N N Air Arabia Maroc 452 3O N N N N N N Air Astana 465 KC Y Y Y N N N N Air Austral 760 UU Y Y N N N N Air Baltic 657 BT Y Y Y N N N Air Belgium 142 KF Y Y N N N N Air Botswana Ltd 636 BP Y Y Y N N N Air Burkina 226 2J N N N N N N Air Canada 014 AC Y Y Y Y Y N N Air China Ltd. 999 CA Y Y N N N N Air Choice One 122 3E N N N N N N Air Côte d'Ivoire 483 HF N N N N N N Air Dolomiti 101 EN N N N N N N Air Europa 996 UX Y Y Y N N N Alaska Seaplanes 042 X4 N N N N N N Air France 057 AF Y Y Y N N N Air Greenland 631 GL Y Y Y N N N Air India 098 AI Y Y Y N N N N Air Macau 675 NX Y Y N N N N Air Madagascar 258 MD N N N N N N Air Malta 643 KM Y Y Y N N N Air Mauritius 239 MK Y Y Y N N N Air Moldova 572 9U Y Y Y N N N Air New Zealand 086 NZ Y Y N N N N Air Niugini 656 PX Y Y Y N N N Air North 287 4N Y Y N N N N Air Rarotonga 755 GZ N N N N N N Air Senegal 490 HC N N N N N N Air Serbia 115 JU Y Y Y N N N Air Seychelles 061 HM N N N N N N Air Tahiti 135 VT Y Y N N N N N Air Tahiti Nui 244 TN Y Y Y N N N Air Tanzania 197 TC N N N N N N Air Transat 649 TS Y Y N N N N N Air Vanuatu 218 NF N N N N N N Aircalin 063 SB Y Y N N N N Airlink 749 4Z Y Y Y N N N Alaska Airlines 027 AS Y Y Y N N N Alitalia 055 AZ Y Y Y N N N All Nippon Airways 205 NH Y Y Y N N N N Amaszonas S.A. -

Silk Road Air Pass: a CAREC Proposal

Silk Road Air Pass: A CAREC proposal Revised Draft, 1 August 2020 This proposal/study was prepared for ADB by Brendan Sobie, Senior Aviation Specialist and Consultant for CAREC Table of Contents: Concept Introduction ……………………………………………………………. Page 2 Summary of Opportunities and Challenges …………………………… Page 3 Historic Examples of Air Passes and Lessons Learned ……………. Page 4 Silk Road Air Pass: The Objective …………………………………………… Page 9 Silk Road Air Pass: Regional International Flights …….…………… Page 11 Silk Road Air Pass: Domestic Flights ………………….…………………. Page 14 Silk Road Air Pass: Domestic Train Travel ..…………………………… Page 18 Silk Road Air Pass: the Two CAREC Regions of China ………….. Page 19 Silk Road Air Pass: Promoting Flights to/from CAREC …………… Page 21 Silk Road Air Pass: Sample Itineraries and Fares…. ………………. Page 23 Conclusion: Why Now? ……………………………………………………….. Page 26 Conclusion: Possible Conditions to Facilitate Success …………. Page 27 Addendum: Embracing New Technology ..………………………….. Page 28 Concept Introduction: Air passes have been used for over three decades by the airline and travel industries to facilitate travel within regions by offering a block of several one-way flights at a discount compared to buying the same flights separately. They are typically sold to tourists from outside the region planning a multi-stop itinerary. By selling a package of flights, often on several airlines, air passes can make travel within a region easier and more affordable, enabling tourists to visit more countries. While their overall track record is mixed, air passes have succeeded in the past at stimulating tourism in several regions, particularly regions that were suffering from high one-way air fares. In recent years one-way air fares have declined significantly in most regions, limiting the appeal of air passes. -

Airplus Company Account: Airline Acceptance

AirPlus Company Account: Airline Acceptance IATA ICAO Country GDS ONLINE (Web) Comments Code Code Acceptance DBI Acceptance DBI Aegean Airlines A3 AEE GR a a a online acceptance: web & mobile Aer Arann RE REA IE a a Aer Lingus P.L.C. EI EIN IE a a a * Aeroflot Russian Intl. Airlines SU AFL RU a a a Aerogal 2K GLG EC a a Aeromar VW TAO MX a a a Aeroméxico AM AMX MX a a a Air Algérie AH DAH DZ a a Air Alps A6 LPV AT a a Air Astana KC KZR KZ a a Air Austral UU REU RE a a Air Baltic BT BTI LV a a Air Busan BX ABL KR a a Air Canada AC ACA CA a a a * Air Caraibes TX FWI FR a a a Air China CA CCA CN a a a a online acceptance in China only Air Corsica XK CCM FR a a Air Dolomiti EN DLA IT a a a Air Europa UX AEA ES a a Air France AF AFR FR a a a * Air Greenland GL GRL GL a a a Air India AI AIC IN a a Air Macau NX AMU MO a a Air Malta KM AMC MT a a a Air Mauritius MK MAU MU a a Air New Zealand NZ ANZ NZ a a a Air Niugini PX ANG PG a a a Air One AP ADH IT a a a Air Serbia JU ASL RS a a a Air Seychelles HM SEY SC a a Air Tahiti Nui VT VTA PF a a Air Vanuatu NF AVN VU a a Air Wisconsin ZW WSN US a a a Aircalin (Air Calédonie Intl.) SB ACI FR a a Air-Taxi Europe - TWG DE a a * AirTran Airways FL TRS US a a a * Alaska Airlines AS ASA US a a a Alitalia AZ AZA IT a a a * All Nippon Airways (ANA) NH ANA JP a a a American Airlines AA AAL US a a a * APG Airlines GP - FR a a a Arik Air W3 ARA NG a a Asiana Airlines OZ AAR KR a a a * Austrian Airlines OS AUA AT a a a a Avianca AV AVA CO a a Azul Linhas Aéreas Brasileiras AD AZU BR a a a Bahamasair UP BHS BS a a Bangkok Airways PG BKP TH a a Bearskin Airlines JV BLS US a a Beijing Capital Airlines JD CBJ CN a a Biman Bangladesh BG BBC BD a a BizCharters (BizAir Shuttle) - - US a a Blue Panorama BV BPA IT a a * Boliviana de Aviación OB BOV BO a a a British Airways BA BAW UK a a a a only one DBI field for online bookings available Brussels Airlines SN BEL BE a a a a Canadian North Inc. -

Discovery Airpass (Bangkok Airways Co., Ltd.) Page 1 Sur 1

Discovery Airpass (Bangkok Airways Co., Ltd.) Page 1 sur 1 | Home | Site Map | Contact Us | Language Quick Access Flight Booking Go Thai regional airline serving over 19 destinations across Asia. BOOKINGS &BOOKING & OFFERS > DISCOVERY AIRPASS TRAVELER I DISCOVERY AIRPASS FLYERBONU CARGO Introduction CHARTER F Fare per coupon in US dollars NEWS RELE GDS Entry for travel agents JOB OPPOR Discovery Airpass route map ABOUT US Introduction E-NEWSLETTER Now Fly to Even More of the Region's Top Destinations and Save! Discovery Airpass will allow you to take advantage of our expanded network which is operated by Bangkok Airways, Subscribe to our Siem Reap Airways International, and our Lao Airlines. For the first time ever, visitors can fly economically cheaply Newsletter and conveniently around the region. It is actually a system of coupons that allows you to fly between Bangkok Airways’ many domestic destinations within Thailand, as well as Siem Reap Airways’ domestic routes in Cambodia, and Lao Airlines’ domestic routes in Laos. Coupons for domestic flights cost USD55 per adult (Children aged 2-11 = USD28; Infants under 2 = USD6)**. The international routes serviced by the participating airlines are also covered. Coupon for most international flight cost USD 90 (Children aged 2-11 = USD68; Infants under 2 = USD9). Certain long distance international flight cost USD150 (Children aged 2-11 = USD113; Infants under 2 = USD15)**. To begin, purchase a minimum of three coupons (or a maximum of six), leaving the dates of all but the first flight of your journey open. Next decide how long you want to stay at each destination and book the next flight of your journey when you are ready to move on. -

Precedent Booking Conditions for Package Holidays Please Read

Precedent Booking Conditions for Package Holidays Please read these booking conditions carefully, they form an important part of the contract for your holiday. All holidays advertised in our brochures and on our website are operated by Exodus Travels Canada Inc. TICO Registered number 002471880 (hereinafter called 'the Company', ‘Exodus’, ’we’, ‘us’ or 'our'), a member of the Travelopia Group of Companies. Registered office: 70 The Esplanade, Suite 401, Toronto, ON, M5E 1R2 and are sold subject to the following conditions: General: If you have any questions arising from the information above, please 1 800 267 3347. We are required to answer any questions you may have about the information contained in these terms and conditions. Insurance. Please Note: Adequate and valid travel insurance is compulsory for all Exodus travelers and it is a condition of accepting your booking that you agree you will have obtained adequate and valid travel insurance for your booking. We recommend you take out insurance as soon as your booking is confirmed. For Certain Tours: You may be asked to accept a separate Contract of Carriage with a local vessel owner/carrier or a local service provider (collectively, the "Carrier") of your cruise which shall govern the relationship, responsibilities and liabilities as between you, the passenger, and the Carrier of your cruise. By agreeing to the Contract of Carriage and accepting the conditions therein, you agree that any dispute that you raise directly with the Carrier will be governed by and subject to the terms and conditions of the Contract of Carriage. For the avoidance of doubt, this Agreement governs the relationship between you and us, and any dispute or claim that you raise with us will be subject to this Agreement and not the Contract of Carriage and to the extent there is a conflict between this Agreement and the provisions of the Contract of Carriage as they relate to you and us, this Agreement shall prevail and supersede the provisions of the Contract of Carriage. -

Laos Overview Principal Offices Affiliate Offices

LAOS OVERVIEW PRINCIPAL OFFICES AFFILIATE OFFICES Vietnam Indonesia Saigon (HQ) - Hanoi Singapore Cambodia Phnom Penh – Siem Reap Hong Kong Laos Luang Prabang Thailand Bangkok – Chiang Mai Myanmar Yangon ABOUT TRAILS OF INDOCHINA Founded in 1999 Centrally managed to serve multi- destination inquiries to Southeast Asia Dedicated customer care team in each of our offices throughout Southeast Asia Exclusive access to local experts in arts, culture, history, culinary experiences & more As experts in tailor-made journeys, we are able to customize every aspect of your clients’ journeys OPERATIONAL HIGHLIGHTS NORTH AMERICAN OFFICE Newport Beach, CA handles initial requests Experienced destination staff NIGHT SHIFT RESERVATIONS TEAM Real-time answers to updates on itineraries Available by toll-free phone or email COMPLETE AGENT SUPPORT Payments are processed in USD funds No credit card fees or wire transfers involved Commission Quotes are net or gross (with commission included) Commission paid when last payment clears AIRPORT FAST-TRACK SERVICE | Extra Expedited immigration process Clients met directly off the plane, accelerated through immigration protocols, and taken directly to private transfer Available in Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Hong Kong and Singapore INTRODUCTION • Established in 1999 and is widely recognized as one of the pioneers to bring luxury and event travel to South East Asia • We operate throughout 9 destinations – Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Myanmar, Indonesia, Singapore, China & Hong Kong. • 250 staff across -

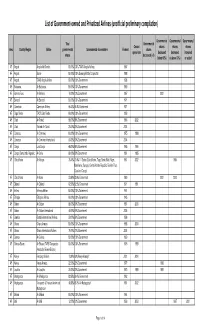

List of Government-Owned and Privatized Airlines (Unofficial Preliminary Compilation)

List of Government-owned and Privatized Airlines (unofficial preliminary compilation) Governmental Governmental Governmental Total Governmental Ceased shares shares shares Area Country/Region Airline governmental Governmental shareholders Formed shares operations decreased decreased increased shares decreased (=0) (below 50%) (=/above 50%) or added AF Angola Angola Air Charter 100.00% 100% TAAG Angola Airlines 1987 AF Angola Sonair 100.00% 100% Sonangol State Corporation 1998 AF Angola TAAG Angola Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1938 AF Botswana Air Botswana 100.00% 100% Government 1969 AF Burkina Faso Air Burkina 10.00% 10% Government 1967 2001 AF Burundi Air Burundi 100.00% 100% Government 1971 AF Cameroon Cameroon Airlines 96.43% 96.4% Government 1971 AF Cape Verde TACV Cabo Verde 100.00% 100% Government 1958 AF Chad Air Tchad 98.00% 98% Government 1966 2002 AF Chad Toumai Air Tchad 25.00% 25% Government 2004 AF Comoros Air Comores 100.00% 100% Government 1975 1998 AF Comoros Air Comores International 60.00% 60% Government 2004 AF Congo Lina Congo 66.00% 66% Government 1965 1999 AF Congo, Democratic Republic Air Zaire 80.00% 80% Government 1961 1995 AF Cofôte d'Ivoire Air Afrique 70.40% 70.4% 11 States (Cote d'Ivoire, Togo, Benin, Mali, Niger, 1961 2002 1994 Mauritania, Senegal, Central African Republic, Burkino Faso, Chad and Congo) AF Côte d'Ivoire Air Ivoire 23.60% 23.6% Government 1960 2001 2000 AF Djibouti Air Djibouti 62.50% 62.5% Government 1971 1991 AF Eritrea Eritrean Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1991 AF Ethiopia Ethiopian -

IATA Members

AIRLINE NAME COUNTRY / TERRITORY Aegean Airlines Greece Aer Lingus Ireland Aero Republica Colombia Aeroflot Russian Federation Aerolineas Argentinas Argentina Aeromar Mexico Aeromexico Mexico Africa World Airlines Ghana Air Algérie Algeria Air Arabia United Arab Emirates Air Astana Kazakhstan Air Austral Réunion Air Baltic Latvia Air Botswana Botswana Air Burkina Burkina Faso Air Cairo Egypt Air Caledonie New Caledonia Air Canada Canada Air Caraibes Guadeloupe Air China China (People's Republic of) Air Corsica France Air Dolomiti Italy Air Europa Spain Air France France Air Guilin China (People's Republic of) Air India India Air Koryo Korea, Democratic People's Republic of Air Macau Macao SAR, China Air Madagascar Madagascar Air Malta Malta Air Mauritius Mauritius AIRLINE NAME COUNTRY / TERRITORY Air Moldova Moldova, Republic of Air Namibia Namibia Air New Zealand New Zealand Air Niugini Independent State of Papua New Guinea Air Nostrum Spain Air Peace Nigeria Air Serbia Serbia Air Seychelles Seychelles Air Tahiti French Polynesia Air Tahiti Nui French Polynesia Air Tanzania Tanzania, United Republic of Air Transat Canada Air Vanuatu Vanuatu AirBridgeCargo Airlines Russian Federation Aircalin New Caledonia Airlink South Africa Alaska Airlines United States Albastar Spain Alitalia Italy Allied Air Nigeria AlMasria Universal Airlines Egypt American Airlines United States ANA Japan APG Airlines France Arik Air Nigeria Arkia Israeli Airlines Israel Asiana Airlines Korea ASKY Togo ASL Airlines France France Atlantic Airways Faroe Islands AIRLINE -

Discovery Airpass

Discovery Airpass **Please note** some routes may operate on a seasonal basis only China BeiBing Kunming Indian Ocean Luang Namtha Oudomxay 0oueisay Myanmar 0ong Kong 0anoi -ieng Khouang Route Network Luang rabang Conditions Chiang Mai Vientiane CMinimum . sectors reDuired Savannakhet Sukhothai )don Thani CMaximum 6 sectors permitted :angon Thailand Laos CDate changes permitted 3OC CAerouting permitted 4 )SD20 akse Bangkok Cambodia C One stopover allowed per city )tapao V i ( attaya) e Siem Aeap (Angkor) t Maldives n a Trat m Male 3ares hnom enh Levels apply per sector & exclude all taxes, surcharges & service fees Indian Ocean Koh Samui huket Krabi C PKZ – REP v.v. M a l Bangkok Airways ( G) only a C Exceptions apply -see belo./ y s Lao Airlines (QV) only i a G and QV Kuala Lumpur C US % BKK,CN(, PK)- VTE/LP, Travel in one direction only Serviced by QV only Singapore C Exceptions apply -see belo./ Serviced by G &/or QV Capital City Bangkok Airways Airport C BKK- LE v.v. Airline Marketing (NZ) Ltd Level 10, 120 Albert St O Box 6247, Wellesley St. A)CKLAND , D- C 2.52. 01 02 262 7600 3-1 02 262 7474 bangkokair4airlinemarketing.co.n6 Discovery Airpass Sale8Ticketing from. Immediate , )3N Departures from. Immediate G )3N New Issue. 01 October 2002 APPLICATION ARE LEVELS Discovery Airpass applies on services operated by Bangkok Minimum of . coupons and a maximum of 6 coupons. Airways ( G) and Lao Airlines (QV) only. Individual sectors may not be travelled more than once in each direction. Each flight number reDuires a coupon. -

DESTINATION LAOS a Briefing for Travel Agents & the Tourism Trade DISCOVER the QUIET HEART of S.E

DESTINATION LAOS A briefing for travel agents & the tourism trade DISCOVER THE QUIET HEART OF S.E. ASIA Curious and enchanting, Laos is a destination unlike any other; a land of untouched wonder and rare beauty, where time loses meaning and simplicity prevails. Rich in history, traditions, diverse landscapes and cultures, Laos captivates the inner explorer, urging them to journey further and deeper into the ‘unknown’. From the rolling mountains of the north to the river islands of the south, our country embraces the visitor in a uniquely laidback lifestyle and the heartfelt generosity of our people. Regardless of travel pace and purpose, the Laos experience never fails to satisfy one’s curiosity – and delivers so much more. Mr Sounh Manivong Director General Tourism Marketing Department Ministry of Information, Culture & Tourism Lao PDR Photo by Jason Rolan CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 1. ABOUT LAOS 6 2. LAOS FOR LEISURE 14 3. LAOS FOR BUSINESS & M.I.C.E. 28 4. SPECIAL INTERESTS 32 5. SUSTAINABLE & RESPONSIBLE TOURISM 38 6. CONNECTIONS 44 COVER PHOTOGRAPH: Jason Rolan British-American ballerina Maria Sascha Khan illustrates her belief in the power of the arts to unite people and cultures, during her first visit to Laos, which was supported by the British Embassy, Panyathip International School and the Crowne Plaza Vientiane. Photo by Jason Rolan 3 www.tourismlaos.org LAOS SIMPLY BEAUTIFUL Our vision is to be a country known for its immersive, diverse experiences while never losing its peaceful, laidback personality. Where did Bangkok’s famous Jade Buddha come from? Laos. Where did the king of Angkor go on pilgrimage? Laos. -

IATA Airline Designators Air Kilroe Limited T/A Eastern Airways T3 * As Avies U3 Air Koryo JS 120 Aserca Airlines, C.A

Air Italy S.p.A. I9 067 Armenia Airways Aircompany CJSC 6A Air Japan Company Ltd. NQ Arubaanse Luchtvaart Maatschappij N.V Air KBZ Ltd. K7 dba Aruba Airlines AG IATA Airline Designators Air Kilroe Limited t/a Eastern Airways T3 * As Avies U3 Air Koryo JS 120 Aserca Airlines, C.A. - Encode Air Macau Company Limited NX 675 Aserca Airlines R7 Air Madagascar MD 258 Asian Air Company Limited DM Air Malawi Limited QM 167 Asian Wings Airways Limited YJ User / Airline Designator / Numeric Air Malta p.l.c. KM 643 Asiana Airlines Inc. OZ 988 1263343 Alberta Ltd. t/a Enerjet EG * Air Manas Astar Air Cargo ER 423 40-Mile Air, Ltd. Q5 * dba Air Manas ltd. Air Company ZM 887 Astra Airlines A2 * 540 Ghana Ltd. 5G Air Mandalay Ltd. 6T Astral Aviation Ltd. 8V * 485 8165343 Canada Inc. dba Air Canada rouge RV AIR MAURITIUS LTD MK 239 Atlantic Airways, Faroe Islands, P/F RC 767 9 Air Co Ltd AQ 902 Air Mediterranee ML 853 Atlantis European Airways TD 9G Rail Limited 9G * Air Moldova 9U 572 Atlas Air, Inc. 5Y 369 Abacus International Pte. Ltd. 1B Air Namibia SW 186 Atlasjet Airlines Inc. KK 610 ABC Aerolineas S.A. de C.V. 4O * 837 Air New Zealand Limited NZ 086 Auric Air Services Limited UI * ABSA - Aerolinhas Brasileiras S.A. M3 549 Air Niamey A7 Aurigny Air Services Limited GR 924 ABX Air, Inc. GB 832 Air Niugini Pty Limited Austrian Airlines AG dba Austrian OS 257 AccesRail and Partner Railways 9B * dba Air Niugini PX 656 Auto Res S.L.U.