Desatoya Mountains Habitat Resiliency, Health, and Restoration Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Paiute and Western Shoshone Land Use in Northern Nevada: a Class I Ethnographic/Ethnohistoric Overview

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bureau of Land Management NEVADA NORTHERN PAIUTE AND WESTERN SHOSHONE LAND USE IN NORTHERN NEVADA: A CLASS I ETHNOGRAPHIC/ETHNOHISTORIC OVERVIEW Ginny Bengston CULTURAL RESOURCE SERIES NO. 12 2003 SWCA ENVIROHMENTAL CON..·S:.. .U LTt;NTS . iitew.a,e.El t:ti.r B'i!lt e.a:b ~f l-amd :Nf'arat:1.iern'.~nt N~:¥G~GI Sl$i~-'®'ffl'c~. P,rceP,GJ r.ei l l§y. SWGA.,,En:v,ir.e.m"me'Y-tfol I €on's.wlf.arats NORTHERN PAIUTE AND WESTERN SHOSHONE LAND USE IN NORTHERN NEVADA: A CLASS I ETHNOGRAPHIC/ETHNOHISTORIC OVERVIEW Submitted to BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Nevada State Office 1340 Financial Boulevard Reno, Nevada 89520-0008 Submitted by SWCA, INC. Environmental Consultants 5370 Kietzke Lane, Suite 205 Reno, Nevada 89511 (775) 826-1700 Prepared by Ginny Bengston SWCA Cultural Resources Report No. 02-551 December 16, 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................v List of Tables .................................................................v List of Appendixes ............................................................ vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................1 CHAPTER 2. ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW .....................................4 Northern Paiute ............................................................4 Habitation Patterns .......................................................8 Subsistence .............................................................9 Burial Practices ........................................................11 -

Hydrographic Basins Information

A p p e n d i x A - B a s i n 54 Crescent Valley Page 1 of 6 Basin 54 - Crescent Valley Crescent Valley is a semi-closed basin that is bounded on the west by the Shoshone Range, on the east by the Cortez Mountains, on the south by the Toiyabe Range, and on the north by the Dry Hills. The drainage basin is about 45 miles long, 20 miles wide, and includes an area of approximately 750 square miles. Water enters the basin primarily as precipitation and is discharged primarily through evaporation and transpiration. Relatively small quantities of water enter the basin as surface flow and ground water underflow from the adjacent Carico Lake Valley at Rocky Pass, where Cooks Creek enters the southwestern end of Crescent Valley. Ground water generally flows northeasterly along the axis of the basin. The natural flow of ground water from Crescent Valley discharges into the Humboldt River between Rose Ranch and Beowawe. It is estimated that the average annual net discharge rate is approximately 700 to 750 acre-feet annually. Many of the streams which drain snowmelt of rainfall from the mountains surrounding Crescent Valley do not reach the dry lake beds on the Valley floor: instead, they branch into smaller channels that eventually run dry. Runoff from Crescent Valley does not reach Humboldt River with the exception of Coyote Creek, an intermittent stream that flows north from the Malpais to the Humboldt River and several small ephemeral streams that flow north from the Dry Hills. Surface flow in the Carico Lake Valley coalesces into Cooks Creek, which enters Crescent Valley through Rocky Pass. -

Eocene–Early Miocene Paleotopography of the Sierra Nevada–Great Basin–Nevadaplano Based on Widespread Ash-Flow Tuffs and P

Origin and Evolution of the Sierra Nevada and Walker Lane themed issue Eocene–Early Miocene paleotopography of the Sierra Nevada–Great Basin–Nevadaplano based on widespread ash-fl ow tuffs and paleovalleys Christopher D. Henry1, Nicholas H. Hinz1, James E. Faulds1, Joseph P. Colgan2, David A. John2, Elwood R. Brooks3, Elizabeth J. Cassel4, Larry J. Garside1, David A. Davis1, and Steven B. Castor1 1Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada 89557, USA 2U.S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, California 94025, USA 3California State University, Hayward, California 94542, USA 4Department of Earth and Environment, Franklin & Marshall College, Lancaster, Pennsylvania 17604, USA ABSTRACT the great volume of erupted tuff and its erup- eruption fl owed similar distances as the mid- tion after ~3 Ma of nearly continuous, major Cenozoic tuffs at average gradients of ~2.5–8 The distribution of Cenozoic ash-fl ow tuffs pyroclastic eruptions near its caldera that m/km. Extrapolated 200–300 km (pre-exten- in the Great Basin and the Sierra Nevada of probably fi lled in nearby topography. sion) from the Pacifi c Ocean to the central eastern California (United States) demon- Distribution of the tuff of Campbell Creek Nevada caldera belt, the lower gradient strates that the region, commonly referred and other ash-fl ow tuffs and continuity of would require elevations of only 0.5 km for to as the Nevadaplano, was an erosional paleovalleys demonstrates that (1) the Basin valley fl oors and 1.5 km for interfl uves. The highland that was drained by major west- and Range–Sierra Nevada structural and great eastward, upvalley fl ow is consistent and east-trending rivers, with a north-south topographic boundary did not exist before with recent stable isotope data that indicate paleodivide through eastern Nevada. -

UNIVERSITY of NEVADA-RENO Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology Un~Vrrsiryof Nevada-8.Eno Reno, Nevada 89557-0088 (702) 784-6691 FAX: (7G2j 784-1709

UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA-RENO Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology Un~vrrsiryof Nevada-8.eno Reno, Nevada 89557-0088 (702) 784-6691 FAX: (7G2j 784-1709 NBMG OPEN-FILE REPORT 90-1 MINERAL RESOURCE INVENTORY BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT, CARSON CITY DISTRICT, NEVADA Joseph V. Tingley This information should be considered preliminary. It has not been edited or checked for completeness or accuracy. Mineral Resource Inventory Bureau of Land Management, Carson City District, Nevada Prepared by: Joseph V. Tingley Prepared for: UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF E INTERIOR '\\ !\ BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Carson City Office Carson City, Nevada Under Cooperative Agreement 14-08-0001-A-0586 with the U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY NEVADA BUREAU OF MINES AND GEOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA, RENO January 1990 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................ 3 LOCATION .......................... 4 MINERAL RESOURCES ...................... 4 MINING DISTRICTS AND AREAS .................. 6 ALLEN HOT SPRINGS AREA ................. 6 ALPINE DISTRICT .................... 7 AURORA DISTRICT .................... 10 BELL DISTRICT ..................... 13 BELLMOUNTAIN DISTRICT ................. 16 BENWAY DISTRICT .................... 19 BERNICE DISTRICT .................... 21 BOVARDDISTRICT .............23 BROKENHILLS DISTRICT ................. 27 BRUNERDISTRICT .................. 30 BUCKLEYDISTRICT ................. 32 BUCKSKINDISTRICT ............... 35 CALICO HILLS AREA ................... 39 CANDELARIA DISTRICT ................. 41 CARSON CITY DISTRICT .................. 44 -

3.2 Land Use

3.2 Land Use No Action Alternative Under the No Action Alternative, the 1999 Congressional land withdrawal of 201,933 acres from public domain (Public Law 106-65) would expire on November 5, 2021, and military training activities requiring the use of these public lands would cease. Expiration of the land withdrawal would terminate the Navy’s authority to use nearly all of the Fallon Range Training Complex’s (FRTC’s) bombing ranges, affecting nearly 62 percent of the land area currently available for military aviation and ground training activities in the FRTC. Alternative 1 – Modernization of the Fallon Range Training Complex Under Alternative 1, the Navy would request Congressional renewal of the 1999 Public Land Withdrawal of 202,864 acres, which is scheduled to expire in November 2021. The Navy would request that Congress withdraw and reserve for military use approximately 618,727 acres of additional Federal land and acquire approximately 65,153 acres of non-federal land. Range infrastructure would be constructed to support modernization, including new target areas, and expand and reconfigured existing Special Use Airspace (SUA) to accommodate the expanded bombing ranges. Implementation of Alternative 1 would potentially require the reroute of State Route 839 and the relocation of a portion of the Paiute Pipeline. Public access to B-16, B-17, and B-20 would be restricted for security and to safeguard against potential hazards associated with military activities. The Navy would not allow mining or geothermal development within the proposed bombing ranges or the Dixie Valley Training Area (DVTA). Under Alternative 1, the Navy would use the modernized FRTC to conduct aviation and ground training of the same general types and at the same tempos as analyzed in Alternative 2 of the 2015 Military Readiness Activities at Fallon Range Training Complex, Nevada, Final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). -

APPENDIX B Late Quaternary Faulting on the Eastgate and Clan

APPENDIX B Late Quaternary Faulting on the Eastgate and Clan Alpine Faults, Nevada Anthony J. Crone and Michael N. Machette U.S. Geological Survey Golden, Colorado FOP Pacific Cell; Eastgate Stop Description 2 Sept 2009 Friends of the Pleistocene, Pacific Cell, Field Trip Stop Description September 2009 Late Quaternary Faulting on the Eastgate and Clan Alpine Faults, Nevada Anthony J. Crone and Michael N. Machette U.S. Geological Survey Golden, Colorado Introduction In the past 137 years, 11 large (M>6.5) historical earthquakes have formed surface ruptures in the Basin-and-Range Province (BRP) of the Intermountain West (de Polo and others, 1991). Six of these historic earthquakes occurred in the north-south-trending Central Nevada Seismic Belt (CNSB; Wallace, 1984), which occupies only a small portion of the BRP. The results of numerous recent paleoseismic studies in the CNSB have shown this cluster of historical earthquakes is anomalous in that a similar sequence of temporally clustered faulting has not been documented during late Quaternary (since 130 ka) time (Bell and others, 2004). Although the slip rates on individual faults in the CNSB, and in the BRP as a whole, are low compared to the slip rates on province-bounding faults associated with the transpressional plate boundary in California, these comparatively low-slip Basin-and-Range faults do pose a significant seismic hazard in urbanized areas such as the Wasatch Front of Utah and the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in western Nevada and eastern California (Truckee-Reno and Las Vegas metropolitan areas), both of which are among the more rapidly growing urban areas in the country. -

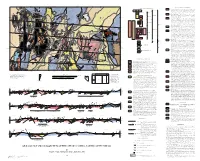

Stratigraphy, Tephrochronology, and Structural Setting of Miocene Sedimentary Rocks in the Middlegate Area, West-Central Nevada by John H

uses science fora changing world Stratigraphy, tephrochronology, and structural setting of Miocene sedimentary rocks in the Middlegate area, west-central Nevada By John H. Stewart, Andrei Sarna-Wojcicki, Charles E. Meyer, Scott W. Starratt, and Elmira Wan U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefield Road, Menlo Park, California, 94025 Open File Report 99-350 1999 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, product or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CONTENTS Abstract . ....................................................................................... 3 Introduction . .................................................................................. 3 Stratigraphy and structure of rocks older than Middlegate Formation .................3 Middlegate Formation........................................................................ 5 Monarch Mill Formation.....................................................................? Paleocurrents directions...................................................................... 12 Environments of deposition................................................................. 12 Paleogeography and structural setting......... ............................................. 14 References cited..................................................................... -

Eocene–Early Miocene Paleotopography of the Sierra Nevada–Great Basin–Nevadaplano Based on Widespread Ash-fl Ow Tuffs and Paleovalleys

Origin and Evolution of the Sierra Nevada and Walker Lane themed issue Eocene–Early Miocene paleotopography of the Sierra Nevada–Great Basin–Nevadaplano based on widespread ash-fl ow tuffs and paleovalleys Christopher D. Henry1, Nicholas H. Hinz1, James E. Faulds1, Joseph P. Colgan2, David A. John2, Elwood R. Brooks3, Elizabeth J. Cassel4, Larry J. Garside1, David A. Davis1, and Steven B. Castor1 1Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada 89557, USA 2U.S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, California 94025, USA 3California State University, Hayward, California 94542, USA 4Department of Earth and Environment, Franklin & Marshall College, Lancaster, Pennsylvania 17604, USA ABSTRACT the great volume of erupted tuff and its erup- eruption fl owed similar distances as the mid- tion after ~3 Ma of nearly continuous, major Cenozoic tuffs at average gradients of ~2.5–8 The distribution of Cenozoic ash-fl ow tuffs pyroclastic eruptions near its caldera that m/km. Extrapolated 200–300 km (pre-exten- in the Great Basin and the Sierra Nevada of probably fi lled in nearby topography. sion) from the Pacifi c Ocean to the central eastern California (United States) demon- Distribution of the tuff of Campbell Creek Nevada caldera belt, the lower gradient strates that the region, commonly referred and other ash-fl ow tuffs and continuity of would require elevations of only 0.5 km for to as the Nevadaplano, was an erosional paleovalleys demonstrates that (1) the Basin valley fl oors and 1.5 km for interfl uves. The highland that was drained by major west- and Range–Sierra Nevada structural and great eastward, upvalley fl ow is consistent and east-trending rivers, with a north-south topographic boundary did not exist before with recent stable isotope data that indicate paleodivide through eastern Nevada. -

ORMAT Technologies Inc. Tungsten Mountain Solar Project Churchill

ORMAT TECHNOLOGIES, INC. 2018 WILDLIFE AND VEGETATION SUPPLEMENTAL TUNGSTEN MOUNTAIN SOLAR PROJECT BASELINE SURVEY AND HABITAT ASSESSMENT ORMAT Technologies Inc. Tungsten Mountain Solar Project Churchill County, Nevada 2018 Supplemental Baseline Wildlife and Vegetation Survey and Habitat Assessment June 28, 2018 1 2018 Tungten Solar Baseline Wildlife and Vegetation Survey and Habitat Assessment_Clean ORMAT TECHNOLOGIES, INC. 2018 WILDLIFE AND VEGETATION SUPPLEMENTAL TUNGSTEN MOUNTAIN SOLAR PROJECT BASELINE SURVEY AND HABITAT ASSESSMENT ORMAT Technologies Inc. Tungsten Mountain Solar Project Churchill County, Nevada 2018 Supplemental Baseline Wildlife and Vegetation Survey and Habitat Assessment June 28, 2018 Prepared for ORMAT Technologies, Inc. 6225 Neil Rd, Reno, NV 89511 Submitted to Bureau of Land Management Stillwater Field Office 5665 Morgan Mill Road Carson City, NV 89701 Fax: 775-885-6147 Phone: 775-885-6000 Prepared by Robison Wildlife Consulting, LLC 5890 Mitra Way Reno, Nevada 89523 Phone: (775) 225-5548 2 2018 Tungten Solar Baseline Wildlife and Vegetation Survey and Habitat Assessment_Clean ORMAT TECHNOLOGIES, INC. 2018 WILDLIFE AND VEGETATION SUPPLEMENTAL TUNGSTEN MOUNTAIN SOLAR PROJECT BASELINE SURVEY AND HABITAT ASSESSMENT 2018 Supplemental Baseline Wildlife and Vegetation Survey and Habitat Assessment June 28, 2018 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 1.1 Purpose of the Desktop Habitat Assessment -

Geologic Map and Cross-Sections of The

117º 00’ 00” 116º 52’ 30” 116º 45’ 00” 116º 37’ 30” CAETANO CALDERA AND RELATED ROCKS Ts? ��� Tbm? �s 35 Pzrm CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS ������ Pzrm ���� 45 s Tcic Carico Lake pluton (Eocene)—Carico Lake pluton consists of 50–60%, 1–5 mm � � � T Pzrm � � 35 L phenocrysts of smoky quartz, sanidine, plagioclase and 2–3% biotite and � � Pzrm Pzrm ��� U s� � A Pzrm Qp Qal Qaf QUATERNARY hornblende in a microcrystalline quartz-feldspar groundmass. Scattered sanidine Tcs ��� Qaf Y � F � � � Tad � 45 s Tbm? Ts E � phenocrysts are as much as 2 cm long. Small miarolitic cavities are common. � � � � � L Tad Pzlc � 40 39 Tad � PLIOCENE 40 � � L Locally flow banded. Intrudes and deforms Caetano Tuff. Sanidine Ar/ Ar � � � s � � � � � Figure 14 � s � � cross-sections only � Greystone QTs �������� Horse A 30 x mine age is 33.78 ± 0.05 Ma (John et al., 2008). l l Tad 06DJ13 E V Mountain N l l l Tcir Redrock Canyon pluton (Eocene)—Strongly altered fine- to medium-grained l 35 Tct? O l Tad l Pzlc T Tbm? Qaf Pipeline pits l l S granite porphyry containing about 30% phenocrysts of rounded smoky quartz Wilson 26 Y l and dumps 21 l 50 Pass NEOGENE Tcb E (2006) and altered sanidine and plagioclase in a felsite groundmass now altered to R Ts R Tob 44 MIOCENE Tmr Qaf Qaf G Gold kaolinite and quartz. Undated but presumed to be late Eocene. Intrudes and 70 E Acres 35 T Tcm 40º 15’ 00” hydrothermally alters Caetano Tuff. D Tcl 33 Tcs CJV2 40º 15’ 00” Tcs 13 Barite N Pzrm Tb Tci R Caetano intrusive rocks, undivided (Eocene)—Small ring-fracture intrusion in Tad Tbm pit E Tcl T O northwestern Carico Lake Valley is a fine- to medium-grained porphyry with Tcs Tad L Qaf C U C T Qaf Unconformity A sparse white K-feldspar phenocrysts as much as 1 cm long. -

Quaternary Fault and Fold Database of the United States

Jump to Navigation Quaternary Fault and Fold Database of the United States As of January 12, 2017, the USGS maintains a limited number of metadata fields that characterize the Quaternary faults and folds of the United States. For the most up-to-date information, please refer to the interactive fault map. Paradise Range fault zone (Class A) No. 1321 Last Review Date: 1998-07-26 citation for this record: Sawyer, T.L., and Lidke, D.J., compilers, 1998, Fault number 1321, Paradise Range fault zone, in Quaternary fault and fold database of the United States: U.S. Geological Survey website, https://earthquakes.usgs.gov/hazards/qfaults, accessed 12/14/2020 02:15 PM. Synopsis This zone of echelon down-to-the-west normal faults bounds the west front of the north-northeast-trending Paradise Range, extends across piedmont slopes in Gabbs Valley and has intermontane faults. In three places south of Gabbs minor surface ruptures occurred along this southern section during the 1932 Cedar Mountain earthquake. The principal sources of data consist of geologic mapping, reconnaissance photogeologic mapping, reconnaissance geomorphic study of fault scarps and basal fault facets, and detailed mapping of 1932 surface ruptures. Name Refers to faults mapped by Gianella and Callaghan (1934 #1515), comments Kleinhampl and Ziony (1985 #2851), Vitaliano and Callaghan (1963 #2916), Dohrenwend and others (1992 #283; 1996 #2846), and Molinari (1984 #1584). dePolo (1998 #2845) referred to it as the Paradise Range fault system and a slight modification of that name is used here. The fault zone extends from southeast of Gold Ledge Mine northward along the eastern side of Gabbs Valley, west of the Paradise Range and through Gabbs. -

Eocene Through Miocene Volcanism in the Great Basin of the Western United States

New Mexico Bureauof Mines & Mineral Resources Memoir 47, May 1989 91 EXCURSION 3A: Eocene through Miocene volcanism in the Great Basin of the western United States Myron G. Best', Eric H. Christiansen', AlanL. Deino", C. Sherman Gromme", 3 4 Edwin H. McKee , and Donald C. Noble 'Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 84602; 'Berkeley Geochronology Center, Berkeley, California 94709; 'U.S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, California 94025; 'University ofNevada, Reno, Nevada 89557 Introduction Geologists of the U.S. Geological Survey, beginning with Cenozoic magmatic rocks in the western United States the Nevada Test Site project in the early and middle 1960's, define a complex space-time-composition pattern that for mapped individual ash-flow sheets over thousands of square many years has posed numerous interpretive challenges. kilometers in the south-central and western Great Basin and One of the more intriguing tectonomagmatic provinces is identified many of their sources. These investigations dem 'the northwestern segment of the Basin and Range province onstrated the feasibility of systematic geologic mapping of in Nevada, western Utah, and minor adjacent parts of Or ash-flow terranes and the utilization of such data for rec egon, Idaho, and California. This segment, characterized ognizing volcanic centers and working out the history of for the most part by internal drainage, is called the Great volcanic fields. Basin (Fig. 1). This paper summarizes characteristics of The magmatic and tectonic development of the Great volcanic rocks in the Great Basin, primarily ash-flow tuff Basin during Cenozoic time was the focus of a number of and subordinate lava, which were.deposited from Eocene papers in the late 1960's and early 1970's based on the body through Miocene time.