Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Asbestos House the Secret History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrating 100 Years, 1908-2008

APS SPORT CENTENARY HISTORY 1908 - 2008 BY G. M. HIBBINS Extended from published edition, minus the individual schools’ histories, plus footnotes. CONTENTS SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY 1. PARADOXICAL ‘PUBLIC’ 2. SOME EARLY GAMES to 1908 3. ‘TO PLAY THE GAME – THE ONLY REAL VICTORY’ 1908-1930 4. THE PRESS 5. THE MOST CHALLENGING GAME OF ALL 6. ‘ADULATION OF THE SPORTING WAS CHILLED’ 1930-1958 7. THE ASSOCIATED PUBLIC SCHOOLS OF VICTORIA EXPAND 8. ‘THE STANDARD STAGGERING AND YET STIMULATING’ 9. THE GIRLS 10. THE APS REGATTAA (HEAD OF THE RIVER) 11. AMATEURS OR PROFESSIONALS? 12. THE PAST, THE PRESENT AND THE FUTURE SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY W. Bate Light Blue Down Under: The History of Geelong Grammar School O.U.P. 1990 W. Bate & H. Penrose Challenging Traditions: A History of Melbourne Grammar 2002 C.E.W. Bean, Here, My Son; an account of the independent and other corporate boys’ schools of Australia Angus and Robertson Sydney 1950 D. Chambers Haileybury College: The First 100 Years Arcadia Melbourne 1992 M. Crotty Making the Australian Male: middle class masculinity 1870-1920 M.U.P. 2001 J. R. Darling The Education of a Civilized Man F.W. Cheshire Melbourne 1962 G. Dening & D. Kennedy, Xavier Portraits, Melbourne, 1993 G. Dening Xavier: A Centenary Portrait Melbourne 1978 H.L. Hall, H. Zachariah, G.F. James Meliora Sequamur: Brighton G.S 1882-1982 Melb.1983 D.E. & I.V. Hansen Yours Sincerely: G.L. Cramer Headmaster Kew Carey B.G.S. 1990 I.V. Hansen Nor Free Nor Secular: six independent schools in Victoria, a first sample, Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1971 B.R. -

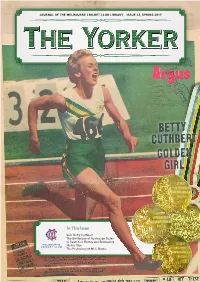

In This Issue

JOURNAL OF THE MELBOURNE CRICKET CLUB LIBRARY ISSUE 63, SPRING 2017 In This Issue Vale Betty Cuthbert The Birthplace of Australian Rules In Search of Fitzroy and Brunswick Mollie Dive The Prehistory of MCC Bowls Level 3, Members Pavilion Melbourne Cricket Ground Contents Yarra Park, Jolimont Telephone +61 3 9657 8876 Facsimile +61 3 9654 6067 Email [email protected] The Birthplace of the Rules 3 Mail PO Box 175 East Melbourne 8002 In Search of Fitzroy and Brunswick 9 Mollie Dive 12 Vale Betty Cuthbert 16 ISSN 1839-3608 The Prehistory of MCC Bowls 19 PUBLISHED BY THE MELBOURNE CRICKET CLUB Book Reviews 28 © THE AUTHORS AND THE MCC The Yorker is edited by Trevor Ruddell with the assistance of David Studham. Graphic design and publication by Library News George Petrou Design. On August 11, the MCC Library’s Research Officer Peta “Pip” Phillips retired after a Thanks to David Allen, Janet Beverley, Libby career of 43 years, 8 Months and 27 Days with the Melbourne Cricket Club. Blessed Blamey, James Brear, Richard Cashman, Robyn with an affable and sincere manner, Peta commenced on November 15, 1973 Calder, Lloyd Carrick, Edward Cohen, Gaye Fitzpatrick, Kate Gray, James Howard, David (coincidently the anniversary of the club’s foundation) as executive assistant to the Langdon, Quentin Miller, Regan Mills, Eric MCC secretary. In that capacity she worked alongside Ian Johnson until 1983, then his Panther, George Petrou, Peta Phillips, Trevor successor Dr John Lill until his retirement in 2000. Thereafter Pip assisted president Ruddell, Ann Rusden, Andrew Trotter, Lesley Smith, David Studham, Eril Wangerek, and the Bruce Church and the committee for a couple of years, before joining David Studham Richmond and Burnley Historical Society. -

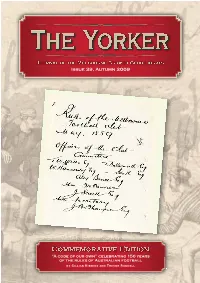

Issue 39, Autumn 2009

Issue 39, Autumn 2009 “A“A code of our own” own” celebrating 150 years of the rules of Australian football by Gillian Hibbins and Trevor Ruddell This Issue This is our fi rst football season issue of the Yorker since 2002 and what better time to revive it than to celebrate the 150th anniversaries of the drafting of the rules of Australian football and the fi rst football match on the current Melbourne Cricket Ground. We feature research articles commemorating the events of 150 years ago by Gillian Hibbins and Trevor Ruddell. You can explore more of the 1859 story of Australian Football in the feature displays on level 1 and 3 of the Pavilion. These are supported by Ross Perry‘s remembrance of the great Australian cyclist and dual Olympic champion Russell Mockridge and an examination of football board games by Eric Panther. Vale Stanley Bannister It is with sadness that we record the passing on April 7 of MCC colleagues. He loved bringing his wife Phyl along to the annual Library volunteer Stanley Bannister at the age of 80. Stan joined Volunteers’ Luncheon, and he was especially proud the year that the Melbourne Cricket Club in January 1981. A frequent attendee of he was presented with his 10 years of volunteer service plaque. events and a regular visitor to the Library on match days, Stan would You’ve never seen such a happy smile as when the President of the come in early to meet friends or have a read and do some research. MCC shook his hand, passed over the award and said “Well done, He’d always have a chat Stanley!” Of course Stan was wearing his beloved club volunteers’ to the library staff on blazer. -

VU Research Repository

In from the Cold: Tom Wills – A Nineteenth Century Sporting Hero By Gregory Mark de Moore A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Human Movement, Recreation and Performance Faculty of Arts, Education and Human Development Victoria University Melbourne, Victoria September 2008 i Abstract Tom Wills was the most important Australian sportsman of the mid-nineteenth century, but it is only in the first decade of the twenty-first century that he has grown in profile as a figure of cultural significance. Although Tom Wills is best recalled as the most important figure in early Australian Rules football, it was cricket that dominated his life. He rose to prominence in cricket during his time at Rugby school in England during the 1850s. When he returned to Australia he became the captain of the Victorian cricket team. On 10 July 1858 he penned what has become one of the most famous documents in Australian sporting history: a letter calling for the formation of a ‘foot- ball’ club. Only three years later his father was murdered by aborigines in central Queensland in what is recorded as the highest number of European settlers killed by aborigines in a single assault. Remarkably, only five years after his father’s murder, Tom Wills coached an aboriginal cricket team from western Victoria. Tom Wills’ life ended early, as did so many lives of colonial sportsmen, shortened by the effects of alcohol. Alcohol abuse led directly to the suicide of Wills at the age of 44 years. This thesis is the first academic attempt to uncover and then critically review some of the important parameters that shaped his life. -

For Club and Country

FOR CLUB AND COUNTRY by Ken Williams MCC Library Volunteer LIBRARY 2000 © The Melbourne Cricket Club Library Published by the MCC Library Melbourne Cricket Ground Yarra Park, East Melbourne 3002 First Published 2000 ISBN 0 9578074 0 6 Printed by: Buscombe Vicprint Typeset in: Garamond, Frutiger Designed by: George Petrou Design CONTENTS FOREWORD 2-3 RIGG, Keith Edward 45-46 BLACKHAM, John McCarthy 4-5 NAGEL, Lisle Ernest 46-47 COOPER, Bransby Beauchamp 6 DARLING, Leonard Stuart 48-49 MIDWINTER, William Evans 7-8 EBELING, Hans Irvine 50-51 KELLY,Thomas Joseph Dart 9-10 FLEETWOOD-SMITH, Leslie O'Brien 52-54 SPOFFORTH, Frederick Robert 10-12 IVERSON, John Bryan 54-57 ALLAN, Francis Erskine 13 McDONALD, Colin Campbell 57-58 ALEXANDER, George 14-15 KLINE, Lindsay Francis 59-60 BONNOR, George John 15-16 GUEST, Colin Ernest John 60-61 McDONNELL, Percy Stanislaus 17-18 WATSON, Graeme Donald 62-63 MOULE, William Henry 19 SHEAHAN, Andrew Paul 64-65 COULTHARD, George 20-21 WALKER, Maxwell Henry Norman 66-67 BRUCE, William 22 MOSS, Jeffrey Kenneth 68 TRUMBLE, John William 23 JONES, Dean Mervyn 69-70 WALTERS, Francis Henry 24 APPENDIX ONE: 71-77 McILWRAITH, John 25 Other Melbourne Cricket Club EDWARDS, John Dunlop 26 Test representatives. TRUMBLE, Hugh 27-28 APPENDIX TWO: 78-79 McLEOD, Robert William 29-30 Players to represent Victoria GRAHAM, Henry 30-31 whilst playing members of the McLEOD, Charles Edward 32-33 Melbourne Cricket Club ARMSTRONG, Warwick Windridge 34-35 APPENDIX THREE: 80 HAZLITT, Gervys Rignold 36-37 Melbourne Cricket Club RANSFORD, Vernon Seymour 38-39 First XI players who played first class HENDRY, Hunter Scott Thomas Laurie 40-41 cricket whilst not playing members PONSFORD, William Harold 42-44 of the club. -

Jared Van Duinen Palgrave Studies in Sport and Politics

PALGRAVE STUDIES IN SPORT AND POLITICS Series Editor: Martin Polley WORLD AND AN AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL IDENTITY Anglo-Australian Cricket, 1860-1901 Jared van Duinen Palgrave Studies in Sport and Politics Series Editor Martin Polley International Centre for Sports History De Montfort University Hampshire, UK Palgrave Studies in Sport and Politics aims to nurture new research, both historical and contemporary, to the complex inter-relationships between sport and politics. The books in this series will range in their focus from the local to the global, and will embody a broad approach to politics, encompassing the ways in which sport has interacted with the state, dissi- dence, ideology, war, human rights, diplomacy, security, policy, identities, the law, and many other forms of politics. It includes approaches from a range of disciplines, and promotes work by new and established scholars from around the world. Advisory Board: Dr. Daphné Bolz, University of Normandy—Rouen, France Dr. Susan Grant, Liverpool John Moores University, UK Dr. Keiko Ikeda, Hokkaido University, Japan Dr. Barbara Keys, University of Melbourne, Australia Dr. Iain Lindsey, Durham University, UK Dr. Ramon Spaaij, Victoria University, Australia and University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15061 Jared van Duinen The British World and an Australian National Identity Anglo-Australian Cricket, 1860–1901 Jared van Duinen Charles Sturt University Wagga Wagga, Australia ISSN 2365-998X ISSN 2365-9998 (electronic) Palgrave Studies in Sport and Politics ISBN 978-1-137-52777-6 ISBN 978-1-137-52778-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-52778-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017944705 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identifed as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

In This Issue : Uncovering Treasures

Journal of the Melbourne Cricket Club Library Issue 42, Spring 2010 in this issue : Uncovering treasures - sorting through the MCC Archives • Myth-busting - Cec Mullen and early football history • MCG’s Aviation Centenary This Issue For our spring 2010 issue we commemorate a centenary volunteers, has been sorting through the records uncovering a (of flight at the MCG), a passing (Major Everett Pope, the Medal real treasure trove of primary source material. Access to the of Honor winner based at the MCG in WWII) and an unveiling archives is closed while material is sorted and inventoried and (of the MCC Archives). The Club’s archive was established as a we finalise the access policy. However, we take great pleasure separate heritage collection in April 2009 with the transferring in sharing some of these treasures with our readers, with three of the corporate records collection to the L2 store room and the pieces helping to shed new light upon our club’s history. On the appointment of Patricia Downs as our first professional archivist. topic primary sources and research, our other feature article Patricia had extensive knowledge of the collections from her (starting this page) shows the importance of historians going work on the MCC Museum inventory project, as a member of the back to check original sources themselves, as Roy Hay examines National Sports Museum production team and on a digitisation long-held myths on early football espoused by pioneer Australian project in the MCC Library. As part of her two year pilot project Football historian Cec Mullen. Patricia, assisted by an enthusiastic team of MCC Library ThE EDITORS Cec Mullen, Tom Wills and the search for early Geelong football Introducing Cec Mullen: Pioneer Sports Historian Clarence Cecil Mullen was born in Richmond in 1895. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources Newspapers The Age. Argus. The Australasian. Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle. Bell’s Life in Victoria and Sporting Chronicle. Birmingham Daily Mail. The Brisbane Courier. The Bulletin. Clarence and Richmond Examiner and New England Advertiser. Nelson Evening Mail. Pall Mall Gazette. Punch, or the London Charivari. The Spectator. Sporting Chronicle. Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser. The Sydney Morning Herald. The Times. Other primary sources Adams, Francis. 2011. First published 1893. The Australians: A Social Sketch. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 73 J. van Duinen, The British World and an Australian National Identity, Palgrave Studies in Sport and Politics, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-52778-3 74 BIBLIOGRAPHY Brumftt, George. 1887. England vs. Australia at the Wicket. Ilkley: Brumftt & Kirby. Cricket. 16 February 1883, p. 9. http://stats.acscricket.com/Cricket/1883/ index.html. Accessed 19 Nov 2015. Deakin, Alfred. 1905. Imperial Federation: An Address Delivered by Hon. In M.P. Alfred Deakin at the Annual Meeting of the Imperial Federation League of Victoria, 14 June 1905. Melbourne: The League. Dilke, Charles. 1869. Greater Britain: A Record of Travel in English-Speaking Countries in 1866-1867. London: Macmillan. Fry, C.B. 1896. Cricket in ’96. New Review. Garran, R.R. 1897. The Coming Commonwealth. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. Giffen, George. 1898. With Bat and Ball: Twenty-Five Years’ Reminiscences of Australian and Anglo-Australian Cricket. London: Ward, Lock and Co. Gould, Nat. 1895. On and Off the Turf in Australia. London: George Routledge. Grace, W.G. -

Maryborough Chronicle Index

Maryborough Chronicle Index Jan 1, 1936 – June 30, 1938 Transcription by Janet Martin, Hervey Bay, Queensland – 2005 Legend for Info: B=Birth / D=Death / Div =Divorce / Eng =Engagement / F=Funeral / Inq =Inquiry / InMem =In Memorium / M=Marriage / O=Obituary / W=Writeup / To search for a name , press CONTROL + F (Windows 'Find' Tool) Date Surname Given Name(s) Info Page 'DD/MM/YYYY' ‘Kewarra’ Man overboard W 20/06/1938 5 ‘Rodney’-Sydney Evidence at W 10/03/1938 9 Harbour Disaster Inquiry ‘Stirling Castle’ Historic wreck W 31/10/1936 3 “Beaumont” Homestead burnt W 11/01/1937 5 “Booubyjan” W 27/08/1937 3 “Cutty Sark” National relic W 05/05/1938 8 Publication “Daily Standard” W 08/07/1936 8 ceases “Ettrickdale” Sale of W 27/08/1937 3 “Highland Plains” Homestead fire W 23/06/1936 5 “Keilawarra” Loss of ship W 17/12/1936 8 Immigrants “Merkara” W 20/11/1937 10 Golden Jubilee 15/05/1937 7 “Minmi” Collier wrecked W 18/05/1937 4 Qld 1 st “Puffing Billy” W 09/05/1936 10 locomotive “Tower Hill”London Historical W 08/05/1937 3 1937 Happenings Events W 01/01/1938 2 40 Hour week Debate W 29/08/1936 9 Inaugural 4MB W 31/05/1937 9 Function Aanensen Andrew W 06/12/1937 6 Abel Les W 30/07/1936 8 Abel Mr Les W W 01/08/1936 10 Date Surname Given Name(s) Info Page 'DD/MM/YYYY' Abercrombie Alan D W 29/10/1937 5 Abercrombie Alan Douglas W 03/09/1937 6 Abercrombie Alan Douglas W 16/10/1937 7 Abercrombie Alan Douglas W 09/11/1937 6 Abercrombie Alan Douglas W 11/11/1937 9 Abercrombie Allan Douglas W 22/09/1937 7 Abercrombie Allan Douglas W 24/09/1937 5 Abood Lillian