Procedural COLUMN Column Editor: Jennifer Wilbeck, DNP, RN, FNP-BC, ACNP-BC, ENP-C, FAANP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Femoral Nerve Block Characteristics Using Ropivacaine 0.2% Alone, with Epinephrine, Or with Lidocaine and Epinephrine

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLES THE FEMORAL NERVE BLOCK CHARACTERISTICS USING ROPIVACAINE 0.2% ALONE, WITH EPINEPHRINE, OR WITH LIDOCAINE AND EPINEPHRINE A.M. TAHA1,2 AND A.M. ABD-ELmaKSOUD31* Keywords: anesthetic techniques, regional, femoral; anaesthetics local, ropivacaine; equipment, ultrasound machines. Abstract Background: The objective of this study was to evaluate the femoral nerve block characteristics (onset, success rate and duration) using ropivacaine 0.2% alone; with epinephrine, or with lidocaine and epinephrine compared with that using ropivacaine 0.5%. Methods: Ninety six patients were included in this prospective controlled double blind study and were randomly allocated into four equal groups (n=24). All the patients received ultrasound guided femoral nerve block using 15 ml of either ropivacaine 0.5% (group 1), ropivacaine 0.2% (group 2), ropivacaine 0.2% with epinephrine (group 3) and ropivacaine 0.2% with lidocaine and epinephrine (group 4). The block onset, success rate and duration were recorded. Results: The motor onset was significantly delayed in group 2 (compared with the other three groups) and in group 3 (compared with group 4). However, the block success rate and duration were comparable in the four groups. Conclusion: In femoral nerve block, ropivacaine 0.2% may have a comparable success rate and duration to ropivacaine 0.5% but with a remarkably delayed motor onset that may be improved by adding epinephrine. Addition of lidocaine may further accelerate the motor onset. Introduction The femoral nerve block (FNB) is a commonly indicated block, and ropivacaine is a widely used long acting local anesthetic (LA)1,2. Peripheral nerve blocks can provide excellent anesthesia and postoperative analgesia 3,4. -

Ultrasound Guided Femoral Nerve Block

Ultrasound Guided Femoral Nerve Block Michael Blaivas, MD, FACEP, FAIUM Clinical Professor of Medicine University of South Carolina School of Medicine AIUM, Third Vice President President, Society for Ultrasound Medical Education Past President, WINFOCUS Editor, Critical Ultrasound Journal Sub-specialty Editor, Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine Emergency Medicine Atlanta, Georgia [email protected] Disclosures • No relevant disclosures to lecture Objectives • Discuss anatomy of femoral nerve • Discuss uses of femoral nerve block classically and 3-in-1 variant • Discuss technique of femoral nerve blockade under ultrasound • Discuss pitfalls and potential errors Femoral Nerve Block Advantages • Many uses of regional nerve blocks • Avoid narcotics and their complications • Allow for longer term pain control • Can be used in patients unfit for sedation – Poor lung health – Hypotensive – Narcotic dependence or sensitivity Femoral Nerve Blocks • Wide variety of potential indications for a femoral nerve block – Hip fracture – Knee dislocation – Femoral fracture – Laceration repair – Burn – Etc. Nerve Blocks in Community vs. Academic Setting • Weekend stays • Night time admissions • Time to get consult and clear • Referral and admission patters • All of these factors can lead to patients spending considerable time prior to OR • Procedural sedation vs. block Femoral Nerve Blocks • Several basic principles with US also • Specialized needles +/- • No nerve stimulator • Can see nerve directly and inject directly around target nerve or nerves • Only -

The International Student Journal of Nurse Anesthesia

Volume 15 Issue 1 Spring 2016 The International Student Journal of Nurse Anesthesia TOPICS IN THIS ISSUE Ondansetron to prevent SAB-induced Hypotension Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase Deficiency Adductor Canal vs. Femoral Nerve Block Ketamine Induction for Awake Intubation Airway Management for Tracheostomy TIVA for Gastroenterology Procedures Hematoma Following Thyroidectomy Tranexamic Acid in Trauma Tracheoesophageal Fistula Reintubation in the PACU Venous Air Embolism Emergence Delirium Preventing OR Fires INTERNATIONAL STUDENT JOURNAL OF NURSE ANESTHESIA Vol. 15 No. 1 Spring 2016 Editor Vicki C. Coopmans, CRNA, PhD Associate Editor Julie A. Pearson, CRNA, PhD Editorial Board Laura Ardizzone, CRNA, DNP Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; NY, NY MAJ Sarah Bellenger, CRNA, MSN, AN Darnall Army Medical Center; Fort Hood, TX Laura S. Bonanno, CRNA, DNP Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center Carrie C. Bowman Dalley, CRNA, MS Georgetown University Marianne Cosgrove, CRNA, DNAP Yale-New Haven Hospital School of Nurse Anesthesia LTC Denise Cotton, CRNA, DNAP, AN Winn Army Community Hospital; Fort Stewart, GA Janet A. Dewan, CRNA, PhD Northeastern University Kären K. Embrey CRNA, EdD University of Southern California Millikin University and Rhonda Gee, CRNA, DNSc Decatur Memorial Hospital Marjorie A. Geisz-Everson CRNA, PhD University of Southern Mississippi Johnnie Holmes, CRNA, PhD Naval Hospital Camp Lejeune Anne Marie Hranchook, CRNA, DNP Oakland University-Beaumont Donna Jasinski, -

Femoral and Sciatic Nerve Blocks for Total Knee Replacement in an Obese Patient with a Previous History of Failed Endotracheal Intubation −A Case Report−

Anesth Pain Med 2011; 6: 270~274 ■Case Report■ Femoral and sciatic nerve blocks for total knee replacement in an obese patient with a previous history of failed endotracheal intubation −A case report− Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, School of Medicine, Catholic University of Daegu, Daegu, Korea Jong Hae Kim, Woon Seok Roh, Jin Yong Jung, Seok Young Song, Jung Eun Kim, and Baek Jin Kim Peripheral nerve block has frequently been used as an alternative are situations in which spinal or epidural anesthesia cannot be to epidural analgesia for postoperative pain control in patients conducted, such as coagulation disturbances, sepsis, local undergoing total knee replacement. However, there are few reports infection, immune deficiency, severe spinal deformity, severe demonstrating that the combination of femoral and sciatic nerve blocks (FSNBs) can provide adequate analgesia and muscle decompensated hypovolemia and shock. Moreover, factors relaxation during total knee replacement. We experienced a case associated with technically difficult neuraxial blocks influence of successful FSNBs for a total knee replacement in a 66 year-old the anesthesiologist’s decision to perform the procedure [1]. In female patient who had a previous cancelled surgery due to a failed tracheal intubation followed by a difficult mask ventilation for 50 these cases, peripheral nerve block can provide a good solution minutes, 3 days before these blocks. FSNBs were performed with for operations on a lower extremity. The combination of 50 ml of 1.5% mepivacaine because she had conditions precluding femoral and sciatic nerve blocks (FSNBs) has frequently been neuraxial blocks including a long distance from the skin to the used for postoperative pain control after total knee replacement epidural space related to a high body mass index and nonpalpable lumbar spinous processes. -

Femoral Nerve Block Versus Spinal Anesthesia for Lower Limb

Alexandria Journal of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care 44 Femoral Nerve Block versus Spinal Anesthesia for Lower Limb Peripheral Vascular Surgery By Ahmed Mansour, MD Assistant Professor of Anesthesia, Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University. Abstract Perioperative cardiac complications occur in 4% to 6% of patients undergoing infrainguinal revascularization under general, spinal, or epidural anesthesia. The risk may be even greater in patients whose cardiac disease cannot be fully evaluated or treated before urgent limb salvage operations. Prompted by these considerations, we investigated the feasibility and results of using femoral nerve block with infiltration of the genito4femoral nerve branches in these high-risk patients. Methods: Forty peripheral vascular reconstruction of lower limbs were performed under either spinal anesthesia (20 patients) or femoral nerve block with infiltration of genito-femoral nerve branches supplemented with local infiltration at the site of dissection as needed (20 patients). All patients had arterial lines. Arterial blood pressure and electrocardiographic monitoring was continued during surgery, in PACU and in the intensive care units. Results: Operations included femoral-femoral, femoral-popliteal bypass grafting and thrombectomy. The intra-operative events showed that the mean time needed to perform the block and dose of analgesics and sedatives needed during surgery was greater in group I (FNB,) compared to group II [P=0.01*, P0.029* , P0.039*], however, the time needed to start surgery was shorter in group I than in group II [P=0. 039]. There were no block failures in either group, but local infiltration in the area of the dissection with 2 ml (range 1-5 ml) of 1% lidocaine was required in 4 (20%) patients in FNB group vs none in the spinal group. -

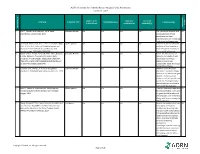

AORN Guideline for Patients Receiving Local-Only Anesthesia Evidence Table

AORN Guideline for Patients Receiving Local-Only Anesthesia Evidence Table SAMPLE SIZE/ CONTROL/ OUTCOME CITATION EVIDENCE TYPE INTERVENTION(S) CONCLUSION(S) POPULATION COMPARISON MEASURE(S) SCORE CONSENSUS REFERENCE # REFERENCE 1 Lirk P., Picardi S. and Hollmann, M. W. Local Literature Review n/a n/a n/a n/a The mechanism of action and VA anaesthetics: 10 essentials. 2014 access pathways of local anesthetics and their pharmokinetics are increasingly understood and appreciated. 2 Calatayud, Jesús, M.D.,D.D.S., Ph.D., González, Õngel, Expert Opinion n/a n/a n/a n/a A review of the discovery and VA M.D., D.D.S., Ph.D. History of the development and evolution of local anesthesia evolution of local anesthesia since the coca leaf. from the Spanish discovery of Anesthesiology. 2003;98(6):1503-1508. the coca leaf in America. 3 Gordh T, M.D., Gordh, Torsten E.,M.D., Ph.D., Lindqvist Literature Review n/a n/a n/a n/a Before the introduction of VA K, M.Sc. Lidocaine: The origin of a modern local lidocaine, the choice of local anesthetic. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(6):1433-1437. anesthetics was limited. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181fcef48. doi: Lidocaine's onset was 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181fcef48. substantially faster and longer lasting than procaine. 4 Volcheck G.W., Mertes, P. M. Local and general Literature Review n/a n/a n/a n/a Whether to test the local VA anesthetics immediate hypersensitivity reactions. 2014 anesthetic causing the allergic reaction or an alternative agent depends on the expected future need of the specific local anesthetic. -

The Use of Buffering Solutions in the Pediatrics Local Anesthesia to Reduce the Pain of Minor Procedures

Volume 2- Issue 1 : 2018 DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.02.000695 Eduardo de Oliveira Duque-Estrada. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res ISSN: 2574-1241 Mini Review Open Access The Use of Buffering Solutions in the Pediatrics Local Anesthesia to Reduce the Pain of Minor Procedures Eduardo de Oliveira Duque-Estrada MD* Received: January 17, 2018; Published: January 25, 2018 *Corresponding author: Eduardo de Oliveira Duque-Estrada, Ex-Professor of Pediatrics and Pediatric Surgery, Teresópolis Schoolof Medicine, Rio de Janeiro, Rua Jose da Silva Ribeiro 119 apt 11 São Paulo, SP Brazil CEP: 05726-130, Email: Abstract The local anesthetics are widely u sed in minor pediatric surgical procedures. The major problem with their use is the resulted pain experienced by the patients at the time of injection. To discuss those situations in the light of the medical literature we present this mini-review. Key words: Local Injection; Pain; Buffer; pH; Lidocaine; Pediatric Surgery Procedure Introduction Table 1: Techniques for injection pain control*. a eutectic mixture of lidocaine and prilocaine (EMLA) cream [17] S.No Techniques for injection pain control before infiltration, and local external cooling (cryoanalgesia) have 1. Warming the anesthetic solution [18,19] (Table 1). also been used to reduce the pain of infiltration of local anesthetic 2. Buffering the anesthetic Buffering the Anesthetic 3. Injection technique 4. Distraction Local anesthesia is extremely useful either as the sole method the best results on the minor surgery in general [3,6]. Blocking 5. Combination anesthetic technique the pain pathway with local anesthetic solution will also reduce 6. Cooling of skin the family stress response to the surgical procedure. -

Veterinary Anesthetic and Analgesic Formulary 3Rd Edition, Version G

Veterinary Anesthetic and Analgesic Formulary 3rd Edition, Version G I. Introduction and Use of the UC‐Denver Veterinary Formulary II. Anesthetic and Analgesic Considerations III. Species Specific Veterinary Formulary 1. Mouse 2. Rat 3. Neonatal Rodent 4. Guinea Pig 5. Chinchilla 6. Gerbil 7. Rabbit 8. Dog 9. Pig 10. Sheep 11. Non‐Pharmaceutical Grade Anesthetics IV. References I. Introduction and Use of the UC‐Denver Formulary Basic Definitions: Anesthesia: central nervous system depression that provides amnesia, unconsciousness and immobility in response to a painful stimulation. Drugs that produce anesthesia may or may not provide analgesia (1, 2). Analgesia: The absence of pain in response to stimulation that would normally be painful. An analgesic drug can provide analgesia by acting at the level of the central nervous system or at the site of inflammation to diminish or block pain signals (1, 2). Sedation: A state of mental calmness, decreased response to environmental stimuli, and muscle relaxation. This state is characterized by suppression of spontaneous movement with maintenance of spinal reflexes (1). Animal anesthesia and analgesia are crucial components of an animal use protocol. This document is provided to aid in the design of an anesthetic and analgesic plan to prevent animal pain whenever possible. However, this document should not be perceived to replace consultation with the university’s veterinary staff. As required by law, the veterinary staff should be consulted to assist in the planning of procedures where anesthetics and analgesics will be used to avoid or minimize discomfort, distress and pain in animals (3, 4). Prior to administration, all use of anesthetics and analgesic are to be approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). -

Local Anesthesia for Carpal Tunnel Surgery

JAMA PATIENT PAGE The Journal of the American Medical Association ANESTHESIOLOGY Administration of local anesthetic Local Anesthesia for carpal tunnel surgery ocal anesthesia is a way to numb a specific area of the body so that a medical procedure can be done without causing pain. Some Loperations, many dental procedures, and different types of diagnostic tests can be done using local anesthesia alone. Local anesthesia medications do not make a person sedated or produce unconsciousness. However, sedation, in which individuals are given medications to make them comfortable and to block memory, is often given along with local anesthesia for many types of procedures. Using local anesthesia alone avoids the side effects of sedation medications and medications used to produce general anesthesia (making an individual unconscious for a procedure). Local anesthetic solutions often provide long-lasting pain relief to the area where they have been applied. Many operations, such as appendectomy (removal of the appendix), cholecystectomy (removal of the gallbladder), and open heart surgery, require general anesthesia. Other procedures, including some orthopedic surgery, urological surgery, and female reproductive Carpal tunnel surgery surgery (including most cesarean deliveries), can be done after a person is given regional anesthesia (such as spinal anesthesia or epidural anesthesia). TYPES OF LOCAL ANESTHESIA • Topical anesthesia places or sprays a solution on the skin or a mucous membrane (such as the mouth, gums, eardrum, inside of the nose, surface of the eye, anus, or vagina). The anesthetic is absorbed where it is applied. Sometimes topical local anesthesia is all that is needed for a FOR MORE INFORMATION procedure, but it can also be part of a combination of other anesthetic techniques. -

Veterinary Anesthesia and Pain Management Secrets / Edited by Stephen A

Publisher: HANLEY & BELFUS, INC. Medical Publishers 210 South 13th Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 (215) 546-7293; 800-962-1892 FAX (215) 790-9330 Web site: http://www.hanleyandbelfus.com Note to the reader Although the information in this book has been carefully reviewed for cor rectness of dosage and indications, neither the authors nor the editor nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. Neither the publisher nor the editor makes any warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein. Before prescribing any drug. the reader must review the manu facturer's correct product information (package inserts) for accepted indications, absolute dosage recommendations. and other information pertinent to the safe and effective use of the product described. This is especially important when drugs are given in combination or as an adjunct to other forms of therapy Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veterinary anesthesia and pain management secrets / edited by Stephen A. Greene. p. em. - (The Secrets Series®) Includes bibliographical references (p.). ISBN 1-56053-442-7 (alk paper) I. Veterinary anesthesia-Examinations, questions. etc. 2. Pain in animals Treatment-Examinations, questions, etc. I. Greene, Stephen A., 1956-11. Series. SF914.V48 2002 636 089' 796'076--dc2 I 2001039966 VETERINARY ANESTHESIA AND PAIN MANAGEMENT SECRETS ISBN 1-56053-442-7 © 2002 by Hanley & Belfus, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro duced, reused, republished. or transmitted in any form, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without written permission of the publisher Last digit is the print number: 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 CONTRIBUTORS G. -

Running Head: ANESTHETIC MANAGEMENT in ERAS PROTOCOLS 1

Running head: ANESTHETIC MANAGEMENT IN ERAS PROTOCOLS 1 ANESTHETIC MANAGEMENT IN ERAS PROTOCOLS FOR TOTAL KNEE AND TOTAL HIP ARTHROPLASTY: AN INTEGRATIVE REVIEW Laura Oseka, BSN, RN Bryan College of Health Sciences ANESTHETIC MANAGEMENT IN ERAS PROTOCOLS 2 Abstract Aims and objectives: The aim of this integrative review is to provide current, evidence-based anesthetic and analgesic recommendations for inclusion in an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol for patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA) or total hip arthroplasty (THA). Methods: Articles published between 2006 and December 2016 were critically appraised for validity, reliability, and rigor of study. Results: The administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, gabapentinoids, and steroids result in shorter hospital length of stay (LOS) and decreased postoperative pain and opioid consumption. A spinal anesthetic block provides benefits over general anesthesia, such as decreased 30-day mortality rates, hospital LOS, blood loss, and complications in the hospital. The use of peripheral nerve blocks result in lower pain scores, decreased opioid consumption, fewer complications, and shorter hospital LOS. Conclusion: Perioperative anesthetic management in ERAS protocols for TKA and THA patients should include the administration of acetaminophen, NSAIDs, gabapentinoids, and steroids. Preferred intraoperative anesthetic management in ERAS protocols should consist of spinal anesthesia with light sedation. Postoperative pain should be -

Local Anesthetic Agents Infiltration: Role of the Nurse

Doug Ducey Joey Ridenour Governor Executive Director Arizona State Board of Nursing 1740 W Adams Street, Suite 2000 Phoenix. AZ 85007 Phone (602) 771-7800 Home Page: http://www.azbn.gov OPINION: INFILTRATION OF LOCAL An advisory opinion adopted by AZBN is an interpretation of what the law requires. While an ANESTHETIC AGENTS: THE ROLE OF THE advisory opinion is not law, it is more than a recommendation. In other words, an advisory opinion NURSE is an official opinion of AZBN regarding the practice of nursing as it relates to the functions of APPROVED DATE: 3/2015 nursing. Facility policies may restrict practice further in their setting and/or require additional REVISED DATE: 7/2018 expectations related to competency, validation, training, and supervision to assure the safety of their patient population and or decrease risk. ORIGINATING COMMITTEE: SCOPE OF PRACTICE COMMITTEE Within the Scope of Practice of X RN x LPN ADVISORY OPINION LOCAL ANESTHETIC AGENTS INFILTRATION: ROLE OF THE NURSE It is within the scope of practice of a registered nurse (RN) and a licensed practical nurse (LPN) to administer certain local anesthetic agents intradermal, subcutaneous, and submucosal for the purposes of analgesia and/or anesthesia prior to potentially painful procedures. Tumescent lidocaine infiltration for ambulatory procedures, such as but not limited to, the treatment of hyperhidrosis, ambulatory phlebectomy and laser facial resurfacings would be within the RN scope under the direction of an licensed independent practitioner (LIP) and when certain criteria is met within this advisory opinion. The licensed nurse must meet the general requirements and course of instruction listed in parts I and II.