Modeling of Compressible Flow with Friction and Heat Transfer Using the Generalized Fluid System Simulation Program (GFSSP)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fluid Mechanics

cen72367_fm.qxd 11/23/04 11:22 AM Page i FLUID MECHANICS FUNDAMENTALS AND APPLICATIONS cen72367_fm.qxd 11/23/04 11:22 AM Page ii McGRAW-HILL SERIES IN MECHANICAL ENGINEERING Alciatore and Histand: Introduction to Mechatronics and Measurement Systems Anderson: Computational Fluid Dynamics: The Basics with Applications Anderson: Fundamentals of Aerodynamics Anderson: Introduction to Flight Anderson: Modern Compressible Flow Barber: Intermediate Mechanics of Materials Beer/Johnston: Vector Mechanics for Engineers Beer/Johnston/DeWolf: Mechanics of Materials Borman and Ragland: Combustion Engineering Budynas: Advanced Strength and Applied Stress Analysis Çengel and Boles: Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach Çengel and Cimbala: Fluid Mechanics: Fundamentals and Applications Çengel and Turner: Fundamentals of Thermal-Fluid Sciences Çengel: Heat Transfer: A Practical Approach Crespo da Silva: Intermediate Dynamics Dieter: Engineering Design: A Materials & Processing Approach Dieter: Mechanical Metallurgy Doebelin: Measurement Systems: Application & Design Dunn: Measurement & Data Analysis for Engineering & Science EDS, Inc.: I-DEAS Student Guide Hamrock/Jacobson/Schmid: Fundamentals of Machine Elements Henkel and Pense: Structure and Properties of Engineering Material Heywood: Internal Combustion Engine Fundamentals Holman: Experimental Methods for Engineers Holman: Heat Transfer Hsu: MEMS & Microsystems: Manufacture & Design Hutton: Fundamentals of Finite Element Analysis Kays/Crawford/Weigand: Convective Heat and Mass Transfer Kelly: Fundamentals -

Introduction to Gas Dynamics All Lecture Slides

Introduction to Gas Dynamics AERODYNAMICS - II All Lecture Slides N. Venkata Raghavendra Farheen Sana Autumn 2009 Gasdynamics — Lecture Slides 1 Compressible flow 2 Zeroth law of thermodynamics 3 First law of thermodynamics 4 Equation of state — ideal gas 5 Specific heats 6 The “perfect” gas 7 Second law of thermodynamics 8 Adiabatic, reversible process 9 The free energy and free enthalpy 10 Entropy and real gas flows 11 One-dimensional gas dynamics 12 Conservation of mass — continuity equation 13 Conservation of energy — energy equation 14 Reservoir conditions 15 On isentropic flows Gasdynamics — Lecture Slides 16 Euler’s equation 17 Momentum equation 18 A review of equations of conservation 19 Isentropic condition 20 Speed of sound — Mach number 21 Results from the energy equation 22 The area-velocity relationship 23 On the equations of state 24 Bernoulli equation — dynamic pressure 25 Constant area flows 26 Shock relations for perfect gas — Part I 27 Shock relations for perfect gas — Part II 28 Shock relations for perfect gas — Part III 29 The area-velocity relationship — revisited 30 Nozzle flow — converging nozzle Gasdynamics — Lecture Slides 31 Nozzle flow — converging-diverging nozzle 32 Normal shock recovery — diffuser 33 Flow with wall roughness — Fanno flow 34 Flow with heat addition — Rayleigh flow 35 Normal shock, Fanno flow and Rayleigh flow 36 Waves in supersonic flow 37 Multi-dimensional equations of the flow 38 Oblique shocks 39 Relationship between wedge angle and wave angle 40 Small angle approximation 41 Mach lines 42 Weak oblique -

Gas Dynamics and Jet Propulsion

A Course Material on GAS DYNAMICS AND JET PROPULSION By Mr. C.RAVINDIRAN. ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING SASURIE COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING VIJAYAMANGALAM – 638 056 QUALITY CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the e-course material Subject Code : ME2351 Subject : GAS DYNAMICS AND JET PROPULSION Class : III Year MECHANICAL ENGINEERING being prepared by me and it meets the knowledge requirement of the university curriculum. Signature of the Author Name : C. Ravindiran Designation: Assistant Professor This is to certify that the course material being prepared by Mr. C. Ravindiran is of adequate quality. He has referred more than five books amount them minimum one is from abroad author. Signature of HD Name: Mr. E.R.Sivakumar SEAL CONTENTS S.NO TOPIC PAGE NO UNIT-1 BASIC CONCEPTS AND ISENTROPIC 1.1 Concept of Gas Dynamics 1 1.1.1 Significance with Applications 1 1.2 Compressible Flows 1 1.2.1 Compressible vs. Incompressible Flow 2 1.2.2 Compressibility 2 1.2.3. Compressibility and Incompressibility 3 1.3 Steady Flow Energy Equation 5 1.4 Momentum Principle for a Control Volume 5 1.5 Stagnation Enthalpy 5 1.6 Stagnation Temperature 7 1.7 Stagnation Pressure 8 1.8 Stagnation velocity of sound 9 1.9 Various regions of flow 9 1.10 Flow Regime Classification 11 1.11 Reference Velocities 12 1.11.1 Maximum velocity of fluid 12 1.11.2 Critical velocity of sound 13 1.12 Mach number 16 1.13 Mach Cone 16 1.14 Reference Mach number 16 1.15 Crocco number 19 1.16 Isothermal Flow 19 1.17 Law of conservation of momentum 19 1.17.1 Assumptions -

Copyrighted Material

BBMIndx.inddMIndx.indd PPageage I-1I-1 111/10/181/10/18 6:536:53 PMPM f-389f-389 //208/WB02304_EVALCS/9781119469582/bmmatter/text_s208/WB02304_EVALCS/9781119469582/bmmatter/text_s Index Absolute pressure, 13, 41 Angular momentum flow, 174, video V5.12 restrictions on use of, 106–110, 222, Absolute temperature Annulus, flow in, 257–258 video V3.12 in British Gravitational (BG) System, 7 Apparent viscosity, 16 unsteady flow, 107–108 in English Engineering (EE) System, 8 Aqueducts, 454 use of, video V3.2 in ideal gas law, 12 Archimedes, 27, 28, 62 Best efficiency points, 564 in International System (SI), 7 Archimedes’ principle, 61–64, video V2.7 Best hydraulic cross section, 460–461 Absolute velocity Area BG units. see British Gravitational (BG) System in centrifugal pumps, 558–561 centroid, 51–53 of units defined, 154, 551 compressible flow with change in, 507–522 Bingham plastic, 16–17 in rotating sprinkler example, 176–177 isentropic flow of ideal gas with change in, Birds, wings of, 429 in turbo machine example, 551–554 510–516 Blades vs. relative velocity, 141–142 and Mach number, 511–513 curved and radia, 561, 562 Absolute viscosity moment of inertia, 52 radial, 561 of air, 620–621 Aspect ratio rotor, 575, 591 of common gases, 617 air foil, 435 stator, 575, 591 of common liquids, 617 plate, 271 turbo machine, 549 defined, 15 Assemblies, 603 Blade velocity, 551–554, 558–559 of U.S. Standard Atmosphere, 622–623 Atmosphere, standard. see Standard Blasius, H., 29, 285, 389 of water, 619 atmosphere Blasius formula, 285, 339 Acceleration -

2006-709: a Web-Based Solver for Compressible Flow Calculations

2006-709: A WEB-BASED SOLVER FOR COMPRESSIBLE FLOW CALCULATIONS Harish Eletem, Lamar University HARISH ELETEM was a graduate student in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Lamar University. He received his M.S. degree in Mechanical Engineering from Lamar University in 2005. Fred Young, Lamar University FRED YOUNG is a professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Lamar University. He received his Ph.D. degree in Mechanical Engineering from Southern Methodist University. He has published many technical papers and presented several papers at international conferences. Kendrick Aung, Lamar University KENDRICK AUNG is an associate professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Lamar University. He received his Ph.D. degree in Aerospace Engineering from University of Michigan in 1996. He is an active member of ASEE, ASME, AIAA and Combustion Institute. He has published over 50 technical papers and presented several papers at national and international conferences. Page 11.144.1 Page © American Society for Engineering Education, 2006 A Web-based Solver for Compressible Flow Calculations Abstract Compressible flow is an important subject in aerospace and mechanical engineering disciplines. This paper describes a web-base solver for carrying out compressible flow calculations. The main objective of the solver is to provide students with a software tool than can be used in the compressible flow course offered in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Lamar University. The solver has a graphical user interface (GUI) for ease of use and interactivity. The solver is capable of solving typical compressible flows such as isentropic flows, Rayleigh and Fanno flows, normal and oblique shock flows, and Prandtl-Myer expansion waves. -

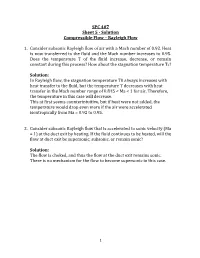

SPC 407 Sheet 5 - Solution Compressible Flow – Rayleigh Flow

SPC 407 Sheet 5 - Solution Compressible Flow – Rayleigh Flow 1. Consider subsonic Rayleigh flow of air with a Mach number of 0.92. Heat is now transferred to the fluid and the Mach number increases to 0.95. Does the temperature T of the fluid increase, decrease, or remain constant during this process? How about the stagnation temperature T0? Solution: In Rayleigh flow, the stagnation temperature T0 always increases with heat transfer to the fluid, but the temperature T decreases with heat transfer in the Mach number range of 0.845 < Ma < 1 for air. Therefore, the temperature in this case will decrease. This at first seems counterintuitive, but if heat were not added, the temperature would drop even more if the air were accelerated isentropically from Ma = 0.92 to 0.95. 2. Consider subsonic Rayleigh flow that is accelerated to sonic velocity (Ma = 1) at the duct exit by heating. If the fluid continues to be heated, will the flow at duct exit be supersonic, subsonic, or remain sonic? Solution: The flow is choked, and thus the flow at the duct exit remains sonic. There is no mechanism for the flow to become supersonic in this case. 1 3. Argon gas enters a constant cross-sectional area duct at Ma1 = 0.2, P1 = 320 kPa, and T1 = 400 K at a rate of 1.2 kg/s. Disregarding frictional losses, determine the highest rate of heat transfer to the argon without reducing the mass flow rate. Solution: Take the properties of argon to be k = 1.667, cp = 0.5203 kJ/kg-K, and R = 0.2081 kJ/kg-K. -

FUNDAMENTALS of FLUID MECHANICS Chapter 11 Analysis of Compressible Flow

FUNDAMENTALSFUNDAMENTALS OFOF FLUIDFLUID MECHANICSMECHANICS ChapterChapter 1111 AnalysisAnalysis ofof CompressibleCompressible FlowFlow JyhJyh--CherngCherng ShiehShieh Department of Bio-Industrial Mechatronics Engineering National Taiwan University 1 MAINMAIN TOPICSTOPICS IdealIdeal GasGas RelationshipsRelationships MachMach NumberNumber andand SpeedSpeed ofof SoundSound CategoriesCategories ofof CompressibleCompressible FlowFlow IsentropicIsentropic FlowFlow ofof anan IdealIdeal GasGas NonisentropicNonisentropic FlowFlow ofof anan IdealIdeal GasGas TwoTwo--DimensionalDimensional CompressibleCompressible FlowFlow 2 IdealIdeal GasGas RelationshipsRelationships 3 IntroductionIntroduction Fluid compressibility is a very important consideration in numerous engineering applications of fluid mechanics. For example, ►►TheThe measurementmeasurement ofof highhigh--speedspeed flowflow velocitiesvelocities requiresrequires compressiblecompressible flowflow theory.theory. ►►TheThe flowsflows inin gasgas turbineturbine engineengine componentscomponents areare generallygenerally compressible.compressible. ►►ManyMany aircraftaircraft flyfly fastfast enoughenough toto involveinvolve aa compressiblecompressible flowflow field.field. In this study of compressibility effects, we mainly consider the steady, one-dimensional, constant (including zero) viscosity, compressible flow of an ideal gas. 4 IdealIdeal GasGas relationshipsrelationships 1/21/2 Before to develop compressible flow equation, we need to become more familiar with the fluid. The equation -

Fundamentals of Compressible Fluid Mechanics

Fundamentals of Compressible Fluid Mechanics Genick Bar–Meir, Ph. D. 1107 16th Ave S. E. Minneapolis, MN 55414-2411 email:[email protected] Copyright © 2006, 2005, and 2004 by Genick Bar-Meir See the file copying.fdl or copyright.tex for copying conditions. Version (0.4.4.2 aka 0.4.4.1j May 21, 2007) `We are like dwarfs sitting on the shoulders of giants” from The Metalogicon by John in 1159 CONTENTS GNU Free Documentation License . xvii 1. APPLICABILITY AND DEFINITIONS . xviii 2. VERBATIM COPYING . xix 3. COPYING IN QUANTITY . xix 4. MODIFICATIONS . xx 5. COMBINING DOCUMENTS . xxii 6. COLLECTIONS OF DOCUMENTS . xxii 7. AGGREGATION WITH INDEPENDENT WORKS . xxiii 8. TRANSLATION . xxiii 9. TERMINATION . xxiii 10. FUTURE REVISIONS OF THIS LICENSE . xxiii ADDENDUM: How to use this License for your documents . xxiv Potto Project License . xxv How to contribute to this book . xxvii Credits . xxvii John Martones . xxvii Grigory Toker . xxviii Ralph Menikoff . xxviii Your name here . xxviii Typo corrections and other ”minor” contributions . xxviii Version 0.4.3 Sep. 15, 2006 . xxxv Version 0.4.2 . xxxv Version 0.4 . xxxvi Version 0.3 . xxxvi Version 4.3 . xli Version 4.1.7 . xlii Speed of Sound . xlvi iii iv CONTENTS Stagnation effects . xlvi Nozzle . xlvi Normal Shock . xlvi Isothermal Flow . xlvi Fanno Flow . xlvii Rayleigh Flow . xlvii Evacuation and filling semi rigid Chambers . xlvii Evacuating and filling chambers under external forces . xlvii Oblique Shock . xlvii Prandtl–Meyer . xlvii Transient problem . xlvii 1 Introduction 1 1.1 What is Compressible Flow ? . 1 1.2 Why Compressible Flow is Important? . -

SPC 407 Sheet 5 Compressible Flow – Rayleigh Flow

SPC 407 Sheet 5 Compressible Flow – Rayleigh Flow 1. Consider subsonic Rayleigh flow of air with a Mach number of 0.92. Heat is now transferred to the fluid and the Mach number increases to 0.95. Does the temperature T of the fluid increase, decrease, or remain constant during this process? How about the stagnation temperature T0? 2. Consider subsonic Rayleigh flow that is accelerated to sonic velocity (Ma = 1) at the duct exit by heating. If the fluid continues to be heated, will the flow at duct exit be supersonic, subsonic, or remain sonic? 3. Argon gas enters a constant cross-sectional area duct at Ma1 = 0.2, P1 = 320 kPa, and T1 = 400 K at a rate of 1.2 kg/s. Disregarding frictional losses, determine the highest rate of heat transfer to the argon without reducing the mass flow rate. 4. Air is heated as it flows subsonically through a duct. When the amount of heat transfer reaches 67 kJ/kg, the flow is observed to be choked, and the velocity and the static pressure are measured to be 680 m/s and 270 kPa. Disregarding frictional losses, determine the velocity, static temperature, and static pressure at the duct inlet. 5. Compressed air from the compressor of a gas turbine enters the combustion chamber at T1 = 700 K, P1 = 600 kPa, and Ma1 = 0.2 at a rate of 0.3 kg/s. Via combustion, heat is transferred to the air at a rate of 150 kJ/s as it flows through the duct with negligible friction. -

Lecture Notes on Gas Dynamics

LECTURE NOTES ON GAS DYNAMICS Joseph M. Powers Department of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering University of Notre Dame Notre Dame, Indiana 46556-5637 USA updated 28 October 2019, 7:15pm 2 CC BY-NC-ND. 28 October 2019, J. M. Powers. Contents Preface 7 1 Introduction 9 1.1 Definitions..................................... 9 1.2 Motivatingexamples ............................... 10 1.2.1 Re-entryflows............................... 10 1.2.1.1 Bowshockwave ........................ 10 1.2.1.2 Rarefaction(expansion)wave . 11 1.2.1.3 Momentumboundarylayer . 11 1.2.1.4 Thermalboundarylayer . 12 1.2.1.5 Vibrational relaxation effects . 12 1.2.1.6 Dissociation effects . 12 1.2.2 Rocketnozzleflows............................ 12 1.2.3 Jetengineinlets.............................. 13 2 Governing equations 15 2.1 Mathematical preliminaries . 15 2.1.1 Vectorsandtensors............................ 15 2.1.2 Gradient, divergence, and material derivatives . .. 16 2.1.3 Conservative andnon-conservative forms . .. 17 2.1.3.1 Conservativeform ....................... 17 2.1.3.2 Non-conservativeform . 17 2.2 Summary of full set of compressible viscous equations . ..... 20 2.3 Conservationaxioms ............................... 21 2.3.1 Conservationofmass........................... 22 2.3.1.1 Nonconservativeform . 22 2.3.1.2 Conservativeform ....................... 22 2.3.1.3 Incompressible form . 22 2.3.2 Conservationoflinearmomenta . 22 2.3.2.1 Nonconservativeform . 22 2.3.2.2 Conservativeform ....................... 23 2.3.3 Conservationofenergy .......................... 24 3 4 CONTENTS 2.3.3.1 Nonconservativeform . 24 2.3.3.2 Mechanicalenergy ....................... 25 2.3.3.3 Conservativeform ....................... 25 2.3.3.4 Energyequationintermsofentropy . 26 2.3.4 Entropyinequality ............................ 26 2.4 Constitutive relations . 29 2.4.1 Stress-strain rate relationship for Newtonian fluids . -

Intro-Propulsion-Lect-22B.Pdf

22-B 1 Lect-22-B In this lecture ... • Shock Waves and Expansion – Normal Shocks – Oblique Shocks – Prandtl–Meyer Expansion Waves • Duct Flow with Heat Transfer and Negligible Friction (Rayleigh Flow) – Property Relations for Rayleigh Flow • Duct flow with friction without heat transfer (Fanno flow) 2 Prof. Bhaskar Roy, Prof. A M Pradeep, Department of Aerospace, IIT Bombay Lect-22-B Shock waves • Sound waves are caused by infinitesimally small pressure disturbances, and travel through a medium at the speed of sound. • Under certain flow conditions, abrupt changes in fluid properties occur across a very thin section: shock wave. • Shock waves are characteristic of supersonic flows, that is when the fluid velocity is greater than the speed of sound. • Flow across a shock is highly irreversible and cannot be approximated as isentropic. 3 Prof. Bhaskar Roy, Prof. A M Pradeep, Department of Aerospace, IIT Bombay Lect-22-B Throat Pe P0 Pb P Pb A P P0 B A Subsonic flow at nozzle exit PB C No shock PC P* D Subsonic flow at nozzle exit PD Shock in nozzle P E Supersonic flow at nozzle exit Sonic flow P F No shock in nozzle at throat PG Inlet Throat Exit x M Shock in nozzle Supersonic flow at nozzle exit No shock in nozzle 1.0 Subsonic flow at nozzle exit D Shock in nozzle C Subsonic flow at nozzle exit B A No shock x 4 Prof. Bhaskar Roy, Prof. A M Pradeep, Department of Aerospace, IIT Bombay Lect-22-B Normal shocks • Shock waves that occur in a plane normal to the direction of flow: Normal shocks. -

ME 510 – Gas Dynamics Final Exam Spring 2009 NAME

ME 510 – Gas Dynamics Final Exam Spring 2009 NAME: 1. (20 pts total – 2pts each) - Circle the most correct answer for the following questions. i. A normal shock propagated into still air travels with a speed (a) equal to the speed of sound in the still air (b) larger than the speed of sound in the still air (c) smaller than the speed of sound in the still air (d) all of the above are possible, depending on the air temperature ii. A perfect gas enters a frictionless, insulated passage with a supersonic speed. It is desired to increase the static pressure of the gas as it flow through the passage. The passage area should: (a) decrease (b) remain constant (c) increase (d) be converging-diverging iii. Which of the following is true for a Fanno flow (a) the Mach number always increases as one moves downstream (b) the static pressure always decreases as one moves downstream (c) the maximum length of the duct is the sonic length (d) none of the above iv. A characteristic curve is a curve (a) across which a variable, e.g. the velocity, is continuous, but the derivatives of that variable are indeterminate (b) the governing PDE can be reduced to an ordinary differential equation (c) along which disturbances in the flow propagate (d) all of the above v. For flow of a compressible fluid from a storage tank through a converging-diverging channel operating under choked conditions (a) the pressure at the exit will be equal to the sonic pressure (b) the flow in the diverging section must be supersonic (c) the mass flow rate through the channel cannot be increased by changing the storage tank conditions (d) none of the above Page 2 of 11 ME 510 – Gas Dynamics Final Exam Spring 2009 NAME: 1.