A Case Study of Ebonyi State Development Centres By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flood Vulnerability Assessment of Afikpo South Local Government Area, Ebonyi State, Nigeria

International Journal of Environment and Climate Change 9(6): 331-342, 2019; Article no.IJECC.2019.026 ISSN: 2581-8627 (Past name: British Journal of Environment & Climate Change, Past ISSN: 2231–4784) Flood Vulnerability Assessment of Afikpo South Local Government Area, Ebonyi State, Nigeria Endurance Okonufua1*, Olabanji O. Olajire2 and Vincent N. Ojeh3 1Department of Road Research, Nigerian Building and Road Research Institute, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria. 2African Regional Centre for Space Science and Technology Education in English, OAU and Centre for Space Research and Applications, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria. 3Department of Geography, Taraba State University, P.M.B. 1167, Jalingo, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration among all authors. Authors EO, OOO and VNO designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the protocol and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors OOO and VNO managed the analyses of the study. Author EO managed the literature searches. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/IJECC/2019/v9i630118 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Anthony R. Lupo, Professor, Department of Soil, Environmental and Atmospheric Science, University of Missouri, Columbia, USA. Reviewers: (1) Ionac Nicoleta, University of Bucharest, Romania. (2) Neha Bansal, Mumbai University, India. (3) Abdul Hamid Mar Iman, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan, Malaysia. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle3.com/review-history/48742 Received 26 March 2019 Accepted 11 June 2019 Original Research Article Published 18 June 2019 ABSTRACT The study was conducted in Afikpo South Local Government covering a total area of 331.5km2. Remote sensing and Geographic Information System (GIS) were integrated with multicriteria analysis to delineate the flood vulnerable areas. -

Analysis of Spring Water Quality in Ebonyi South Zone and Its Health Impact 1J.N

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC AND INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH © 2013, Science Huβ, http://www.scihub.org/AJSIR ISSN: 2153-649X, doi:10.5251/ajsir.2013.4.2.231.237 Analysis of spring water quality in Ebonyi South Zone and its health impact 1J.N. Afiukwa and 2A.N. Eboatu 1Department of Industrial Chemistry, Ebonyi State University Private Mail Bag 053, Abakaliki, Nigeria 2Department of Pure and Industrial Chemistry, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria. ABSTRACT Studies were carried out between June through December, 2007 to evaluate the quality of rural water supply for drinking in Ebonyi South Zone of Ebonyi State, Nigeria. The rural communities of Ekoli Edda and Ozizza in Afikpo South L.G.A and parts of Okposi in Ohaozara L.G.A depend solely on spring water for their domestic needs. Samples from seven spring water sources in these areas were analyzed for some physico-chemical and microbial parameters by standard methods. Concentrations of some heavy metals; Cr, Cd, Co, Cu, Fe, Mn, Pb, Ni and Zn were determined using Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer. The results of the chemical analysis compared favourably with the WHO standard for drinking water, except for the relatively high concentration of iron in samples SE 5 (0.79 mg/L) and SE 6 (0.58 mg/L), and the exceedingly high phosphate concentrations, ranging from 0.25 - 1.6mg/L in all the samples as against the WHO permissible limit of 0.1mg/L. The bacteriological analyses however revealed about 40% total coliform bacteria contamination, varying between 0 - 4 MPN/100 ml of water in five out of the seven samples tested. -

World Bank Document

ESMP for Nguzu Edda (Afikpo South LGA Headquarters) Gully Erosion site in Ebonyi State Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN (ESMP) (Final Draft Report) For NGUZU EDDA (AFIKPO SOUTH LOCAL GOVERNMENT HEADQUARTERS) GULLY EROSION INTERVENTION SITE, EBONYI STATE Public Disclosure Authorized UNDER Public Disclosure Authorized THE NIGERIA EROSION & WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PROJECT (NEWMAP) WORLD BANK ASSISTED By EBONYI STATE -NIGERIA EROSION & WATERSHED MANAGEMENT PROJECT (EBS-NEWMAP) ABAKALIKI, EBONYI STATE Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized June, 2014 ESMP for Nguzu Edda (Afikpo South LGA Headquarters) Gully Erosion site in Ebonyi State ESMP for Nguzu Edda (Afikpo South LGA Headquarters) Gully Erosion site in Ebonyi State Table of Contents Content Page Cover Page i Table of Contents ii List of Tables v List of Figures vi List of Maps vi List of Boxes vi List of Abbreviations/ Acronyms vii Definition of Terms ix Executive Summary x CHAPTER 1: GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background 2 1.2 The proposed Intervention Work 3 1.3 Need for ESMP for the Proposed Intervention Work 4 1.4 Objectives of this Environmental and Social Management Plan 4 1.5 Scope/Terms of Reference of the ESMP and Tasks 4 1.6 Approaches for Preparing the Environmental and Social Management Plan 4 1.6.1 Literature Review 4 1.6.2 Interactive Discussions/Consultations 4 1.6.3 Field Visits 4 1.6.4 Identification of Potential Impacts and Mitigation Measures 4 CHAPTER 2: INSTITUTIONAL AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Utilization of Selected Vitality Staple Foods by Low Income Households in Ebonyi State

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.6, No.31, 2015 Utilization of Selected Vitality Staple Foods by Low Income Households in Ebonyi State Igba, Chimezie Elizabeth Ph.D Department of Home Economics,Ebonyi State Universty, Abakaliki, Nigeria M O Okoro Prof Department of Vocational Teacher Education, University of Nigeria, Nsukka Abstract The study focused on the utilization of selected vitality foods among low income household in Ebonyi State. Specifically the study aimed at identifying vitality foods that are available, accessible and utilized by low income household in state. Descriptive survey design was used for the study. The population of the study is 2,173,501 households and the sample size is 400 households. The instrument for data collection was questionnaire and interview. The research questions were answered on individual item basis using mean, frequency and standard deviation, t-test was used to test the hypothesis. The findings revealed among other things that vitality foods are not always available in the state; they are not always accessible and therefore not always utilized by the low income households in the state. This is contrary to US Department of Agriculture Food Guide Pyramid that children should consume three servings from the vitality foods each day to remain healthy. Based on the findings, some recommendations were made including (1) Nutrition education at the household level should be taught by Home Economics Extension workers to family members through workshops/seminars as this will encourage low income households on ways of reducing food insecurity during off seasons (2) Entrepreneurship education should be introduced into the school curriculum from primary to university levels of education to empower low income households financially among others. -

Prevalence of Paragonimus Infection

American Journal of Infectious Diseases 9 (1): 17-23, 2013 ISSN: 1553-6203 ©2013 Science Publication doi:10.3844/ajidsp.2013.17.23 Published Online 9 (1) 2013 (http://www.thescipub.com/ajid.toc) Prevalence of Paragonimus Infection 1Nworie Okoro, 2Reginald Azu Onyeagba, 3Chukwudi Anyim, 4Ogbuinya Elom Eda, 3Chukwudum Somadina Okoli, 5Ikechukwu Orji, 3Eucharia Chinyere Okonkwo, 3Uchechukwu Onyeukwu Ekuma and 3Maduka Victor Agah 1Department of Biological Science, Faculty of Science and Technology, Federal University Ndufu Alike-Ikwo, Nigeria 2Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Biological and Physical Sciences, Abia State University, Uturu-Okigwe, Nigeria 3Department of Applied Microbiology, Faculty of Biological Science, Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki, Nigeria 4Hospital Management Board, Ministry of Health, Abakaliki, Nigeria 5Federal Teaching Hospital Abakaliki II (FETHA II), Abakaliki, Ebonyi, Nigeria Received 2013-01-25, Revised 2013-02-19; Accepted 2013-05-20 ABSTRACT Paragonimiasis (human infections with the lung fluke Paragonimus westermani ) is an important public health problem in parts of Africa. This study was aimed at assessing the prevalence of Paragonimus infection in Ebonyi State. Deep sputum samples from 3600 individuals and stool samples from 900 individuals in nine Local Government Areas in Ebonyi State, Nigeria were examined for Paragonimus ova using concentration technique. The overall prevalence of pulmonary Paragonimus infection in the area was 16.30%. Six foci of the infection were identified in Ebonyi North and Ebonyi Central but none in Ebonyi South. The intensity of the infection was generally moderate. Of the 720 individuals examined, 16 (12.12%) had less than 40 ova of Paragonimus in 5 mL sputum and 114 (86.36%) had between 40 and 79 ova of Paragonimus in 5 mL sputum. -

Assessment and Management Strategies for the Receding

Journal of Environment and Earth Science www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3216 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0948 (Online) Vol. 3, No.3, 2013 Assessment and Management Strategies for the Receding Watersheds of Ebonyi State, Southeast Nigeria Ogbodo E N Department of Soil and Environmental Management, Ebonyi State University, PMB 053,Abakaliki, Ebonyi State, Nigeria Email: emmanwaogbodo@ yahoo. com. Abstract The conditions of the watersheds of Ebonyi State has become a concern for individuals, communities, governments, donor agencies and private and public businesses as everybody depends on its resources. A study was therefore conducted within 2011 to 2012, to identify the dimensions and level of environmental degradation at the watershed sites with a view to developing management strategies for them. The study involved global positioning, reconnaissance survey and evaluation. The assessments of the sites identified were based on technical judgments, using the environmental baseline data collection and secondary information methods. A total of 39 degraded watersheds were identified, and which environmental assessment was carried out on. The results indicated that erosion, siltation and deforestation were the major environmental degradations, and cutting across almost the entire watersheds. Previous restoration measures were reviewed and recommendations for future conservation strategies were highlighted. Key words: Receding watersheds, Degradation, Environmental assessment, Management, Ebonyi state. 1. Introduction A Watershed is a land area whose runoff drains into any stream, river, lake, and ocean. Other terms used for watershed include catchment or drainage basin . The watersheds consist of land, water and the shed; the vegetative canopy that assists in maintenance of the dynamic equilibrium in the watershed ecosystem. Watersheds are uniquely multifunctional and capable of simultaneously producing agricultural commodities and generating ecosystem services. -

Profile of Some Trace Elements in Selected Traditional Medicines Used for Various Aliments in Ebonyi State, Nigeria

American Journal of www.biomedgrid.com Biomedical Science & Research ISSN: 2642-1747 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Research Article Copy Right@ Obeta Mark Uchejeso Profile of Some Trace Elements in Selected Traditional Medicines used for Various Aliments in Ebonyi State, Nigeria Ikeagwulonu Richard Chinaza1,6, Nkereuwem Sunday Etukudoh2, Ejinaka Obiora Reginald3, Ibanga Imoh Etim4, Obeta Mark Uchejeso4*, Uro-Chukwu Henry Chukwuemeka5 and Odeh Elizabeth Chibuzor6 1Department of Medical Laboratory Science, College of Health Sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Nigeria 2Department of Haematology, Federal School of Medical Laboratory Science, Jos-Nigeria 3Department of Parasitology, Federal School of Medical Laboratory Science, Jos-Nigeria 4Department of Chemical Pathology, Federal School of Medical Laboratory Science, Jos-Nigeria 5Department of Community Medicine, College of Health Science, Ebonyi State University, Nigeria 6Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Alex Ekwueme Federal University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria *Corresponding author: Obeta Mark Uchejeso, Department of Chemical Pathology, Federal School of Medical Laboratory Science, Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria. To Cite This Article: Ikeagwulonu Richard C, Nkereuwem Sunday E, Ejinaka Obiora R, Ibanga Imoh E, Obeta Mark U, et al., Profile of Some Trace Elements in Selected Traditional Medicines used for Various Aliments in Ebonyi State, Nigeria. 2020 - 9(3). AJBSR.MS.ID.001396. DOI: -

(GBV) SERVICES REFERRAL DIRECTORY for EBONYI STATE, NIGERIA

GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE (GBV) SERVICES REFERRAL DIRECTORY for EBONYI STATE, NIGERIA Name & Address of Organization Coverage Area Contact Information A HEALTH – Closest referral hospital B PSYCHOSOCIAL COUNSELING Faith Community Counseling Organization (FCCO) Opposite WDC ●Ohaukwu Abakaliki ● Izzi●Ezza Mrs. Margaret Nworie:080-3585-5986 Abakaliki South●Ezza North [email protected] C SHELTER/SAFE HOUSE Safe Motherhood Ladies Association (SMLAS) Mgboejeagu Cresent GRA ●Ohaukwu●Afikpo South●Ezza Mrs. Ugo Ndukwe Uduma: 080-3501-0168 off Ezra Road, Abakaliki South●Abakaliki●Ebonyi●Ohaozara [email protected] Afikpo North●Ishielu Ohaukwu: 070-54178753 Afikpo South: 081-4476-2576 Ezza South: 081-3416-5414 Abakaliki: 070-3838-3692 Izzi: 080-6047-2525 Ebonyi: 080-8877-0802 Ohaozara: 080-6465-2152 Afikpo North: 080-3878-8868; 070-30546995 Ishielu: 080-6838-0889 Family Law Centre No. 47/48, Ezza Road, Abakaliki ●Abakaliki, Ebonyi State Edith Ngene: 080-3416-2207 NSCDC Abakaliki No 8 Town Planning Road P O Box 89 Abakaliki ●Office exists in all LGA Secretariat State Commandant: 080-3669-4912 in the State State PRO: 080-3439-5063 [email protected] NAPTIP Centenary City, 1st Floor Block 10, SMOWAD ●All LGAs Florence Nkechinyere Onwa: 080-3453-4785 D SOCIAL RE-INTEGRATION & ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT Widow Care Foundation Kilometer 10, Abakaliki-Enugu Expressway ● Abakaliki Mrs. Grace Agbo: 080-3343-1993 Opp. Liberation Estate Abakaliki [email protected] Child Emancipation and Welfare Organization (CEWO) Inside LGA Office, ●Abakaliki Hon. Ishiali Christian: 080-3733-9036 Ohaukwu Catholic Diocese of Abakaliki Succor and Development (SUCCDEV) ●Ohaukwu●Ebonyi●Amaike Aba Sis Cecilia Chukwu: 080-3355-5846 Amaike Aba, Ebonyi LGA, Ebonyi State. -

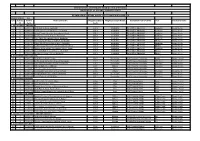

EBONYI STATE 33 S/N S/N for CP Centre Code Name of Centre

SENIOR SCHOOL CERTIFICATE EXAMINATION (EXTERNAL) MASTER LIST OF CENTRES IN EBONYI STATE EXAMINATION CENTRES, CODES AND THEIR NEIGHBOURHOOD EBONYI STATE 33 S/n S/n for Centre Name of Centre Neighbourhood Neighbourhood Name Custodian Point/Outlet LGA Senatorial zone CP Code Code 1. NECO OFFICE ABAKALIKI 1 1 0330001 Girls High School, Abakaliki 3301 Abakaliki Neco Office Abakaliki Abakaliki Ebonyi North 2 2 0330002 Command Secondary School, Abakaliki 3301 Abakaliki Neco Office Abakaliki Abakaliki Ebonyi North 3 3 0330003 Bethel Comprehensive Secondary School 3301 Abakaliki Neco Office Abakaliki Abakaliki Ebonyi North 4 4 0330004 Trinity Secondary School, Abakaliki 3301 Abakaliki Neco Office Abakaliki Abakaliki Ebonyi North 5 5 0330008 Holy Ghost Secondary School, Abakaliki 3301 Abakaliki Neco Office Abakaliki Abakaliki Ebonyi North 6 6 0330009 Government Technical College, Abakalilki 3301 Abakaliki Neco Office Abakaliki Ebonyi Ebonyi North 7 7 0330010 Urban Model Secondary School, Abakaliki 3301 Abakaliki Neco Office Abakaliki Abakaliki Ebonyi North 8 8 0330011 Model Comprehensive Girls Secondary School 3301 Abakaliki Neco Office Abakaliki Ebonyi Ebonyi North 9 9 0330022 Ginger International Secondary School, Abaki 3301 Abakaliki Neco Office Abakaliki Abakaliki Ebonyi North 10 10 0330023 Abakaliki High School Presco, Abakaliki 3301 Abakaliki Neco Office Abakaliki Ebonyi Ebonyi North 11 11 0330030 Nnodo Secondary School Ababaliki 3301 Abakaliki Neco Office Abakaliki Ebonyi Ebonyi North 4. SUB TREASURY EZZAMGBO 15 1 0330015 Girls High School, -

National Assembly 2071 2013 Appropriation

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA 2012 BUDGET SUMMARY FEDERAL MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT TOTAL OVERHEAD CODE TOTAL PERSONNEL TOTAL RECURRENT TOTAL CAPITAL TOTAL ALLOCATION COST MDA COST =N= =N= =N= =N= =N= 0535001001 MAIN MINISTRY 154,077,328 325,153,770 479,231,098 9,257,672,550 9,736,903,648 0535002001 NATIONAL PARK HEADQUARTER 142,697,404 90,335,409 233,032,813 606,060,008 839,092,821 0535003001 KAINJI LAKE NATIONAL PARK 342,889,081 75,235,124 418,124,205 10,000,000 428,124,205 0535004001 OLD OYO NATIONAL PARK 243,239,134 75,804,391 319,043,525 29,500,000 348,543,525 0535005001 CHAD BASIN NATIONAL PARK 202,953,024 77,943,517 280,896,540 19,900,000 300,796,540 0535006001 GASHAKA GUMTI NATIONAL PARK 249,350,902 80,277,492 329,628,394 49,400,000 379,028,394 0535007001 CROSS RIVER NATIONAL PARK 337,685,668 90,184,292 427,869,960 620,000,000 1,047,869,960 0535008001 KUMUKU NATIONAL PARK 142,531,836 76,173,544 218,705,380 35,000,000 253,705,380 0535009001 OKUMU NATIONAL PARK 136,862,654 77,004,109 213,866,763 10,000,000 223,866,763 FEDERAL COLLEGE OF WILD LIFE 0535010001 MANAGEMENT NEW BUSSA 348,377,873 125,089,396 473,467,269 50,000,000 523,467,269 0535011001 FEDERAL COLLEGE OF FORESTRY IBADAN 691,884,226 120,961,152 812,845,378 34,806,203 847,651,581 0535012001 FEDERAL COLLEGE OF FORESTRY, JOS 470,270,647 150,713,191 620,983,838 280,295,507 901,279,345 FORESTRY RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF NIGERIA, 0535013001 IBADAN 1,468,773,710 299,668,324 1,768,442,034 186,510,623 1,954,952,657 0535014001 FORESTRY MECHANISATION COLLEGE, AFAKA 413,536,783 100,558,024 -

Linguistic and Geographical Survey of Ebonyi State, South East Nigeria

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 10 Issue 5 Ser. I || May 2021 || PP 01-10 Linguistic and Geographical Survey of Ebonyi State, South East Nigeria 1Evelyn Chinwe Obianika, 1Ngozi U. Emeka-Nwobia, 1Mercy Agha Onu, 1Maudlin A. Eze, 1Iwuchukwu C. Uwaezuoke, 2Okoro S. I., 3Igba D. I., 1Henrietta N. Ajah, 1Emmanuel Nwaoke and Ogbonnaya Joseph Eze 1Department of Linguistics and Literary Studies, Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki. 2Department of History and International Relations, Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki. 3Department of Arts and Social Science Education, Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki. 4Department of Geography, Ebonyi State College of Education, Ikwo Abstract The objective of this study was to identify the major languages spoken in Ebonyi State, their dialects and geographical locations presented in a map. The survey research method was used. Data collection was carried out using personal interview and Focus Group Discussion (FGD) methods. Three men and three female respondents were sampled from each dialect/ethnic group using purposive random sampling and data collection sessions were recorded electronically. The data were analyzed using the descriptive and inferential methods. In the results, two languages were identified in the state; the Igbo and Korin languages. The study found out that the Korin language is spoken in nine major communities and has five identifiable dialects spanning three local government