The United States Army Chaplaincy 1920-"1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary Justice: the Price of Treason for Eight World War Ii German Prisoners of War

SUMMARY JUSTICE: THE PRICE OF TREASON FOR EIGHT WORLD WAR II GERMAN PRISONERS OF WAR A Thesis by Mark P. Schock Bachelor of Arts, Kansas Newman College, 1978 Submitted to the Department of History and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of Master of Arts May 2011 © Copyright 2011 by Mark P. Schock All Rights Reserved SUMMARY JUSTICE: THE PRICE OF TREASON FOR EIGHT WORLD WAR II GERMAN PRISONERS OF WAR The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content, and recommended that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts with a major in History. ___________________________________ Robert Owens, Committee Chair ___________________________________ Robin Henry, Committee Member ___________________________________ William Woods, Committee Member iii DEDICATION To the memory of my father, Richard Schock, and my uncle Pat Bessette, both of whom encouraged in me a deep love of history and country iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank my adviser, Dr. Robert Owens, for his incredible patience with an old dog who had such trouble with new tricks. Special thanks go to Dr. Anthony and Dana Gythiel whose generous grant allowed me to travel to the National Archives and thus gain access to many of the original documents pertinent to this story. I’d also like to thank Colonel Jack Bender, U.S.A.F (ret.), for his insight into the workings of military justice. Special thanks are likewise due to Lowell May, author of two books about German POWs incarcerated in Kansas during World War II. -

Chaplaincy in Anglican Schools

CHAPLAINCY IN ANGLICAN SCHOOLS GUIDELINES FOR THE CONSIDERATION OF BISHOPS, HEADS OF SCHOOLS, CHAPLAINS, AND HEADS OF THEOLOGICAL COLLEGES THE REVEREND DR TOM WALLACE ON BEHALF OF THE AUSTRALIAN ANGLICAN SCHOOLS NETWORK ANGLICAN CHURCH OFFICE 26 KING WILLIAM ROAD NORTH ADELAIDE SA 5006 AUGUST 1999 1 CHAPLAINCY IN ANGLICAN SCHOOLS GUIDELINES FOR BISHOPS, HEADS OF SCHOOLS AND CHAPLAINS 1. BACKGROUND At the National Anglican Schools Conference held at Melbourne Girls’ Grammar in April 1997 the National Anglican Schools Consultative Committee was asked to conduct a survey on Religious Education and Chaplaincy in Anglican schools in Australia. The Survey was conducted on behalf of the Committee by Dr Peter Coman, Executive Director of the Anglican Schools Office in the Diocese of Brisbane in February 1998. An Interim Report was presented to the National Conference in May 1998. The Rev’d Dr Tom Wallace of the Anglican Schools Commission in Western Australia was asked to give consideration to ways in which the Report may be followed up and a small consultative committee, representative of all the States, was appointed to work with him. It was agreed that Dr Wallace would prepare a discussion paper on Chaplaincy in Anglican Schools, which would be considered initially by members of the representative committee with a view to wider circulation to Principals, Chaplains and Diocesan Bishops. That discussion paper was prepared and feedback on it was received from several Chaplains from three Australian States. As a result of the feedback the Paper was revised with a view to it being considered at a national gathering of Chaplains at the National Anglican Schools Conference in May 1999. -

The History of the New York State Association of Fire Chaplains, Inc

The History of the New York State Association of Fire Chaplains, Inc. Celebrating the Association’s 2016 (Updated October 7, 2017) Table of Contents SS Dorchester .............................................................................................. 3 Chaplains’ Seminar at FASNY - 1966 ......................................................... 4 Incorporation ................................................................................................ 7 Support of Fire Chiefs and FASNY .............................................................. 8 Chaplain’s Manual........................................................................................ 8 1970’s Conferences ..................................................................................... 9 Fire Academy Established ........................................................................... 9 Women in Fire Service ............................................................................... 10 1980’s Conferences ................................................................................... 10 Lay Chaplains ............................................................................................ 11 1994 - Lay Chief Chaplain ......................................................................... 12 2000’s Conferences ................................................................................... 14 FASNY Chaplains’ Committee ................................................................... 16 Marriage Renewal Service - 2006 ............................................................ -

Standards for the Work Of. the .Chaplain in the General Hospital

fillicia11y Adopted by the Am . .Ptot..estant H09P,;+~ 1 A encal1 '.B' _Lal. BSll. at th . OBton Conven~ion c_ te be Q v. ~p m r 194(}. Standards for the Work of. the .Chaplain in the General Hospital REV. RUSSELL L. DICKS, D.O. T has come to the attention of the American The Author Protestant Hospital Association that the • Rev. Russell L. Dicks, D.D., is Chaplain I spiritual needs of many patients, both in pri of the Presbyterian Hospital, Chic~go, and vate and public institutions, are not receiving Chairman of the Special Study Committee proper attention. In some instances patients are that prepared these Standards. not receiving any spiritual care, in others they are receiving altogether too much. We know of with the clergyman's ordination vows or his institutions where as many as seven or eight higher loyalties. different religious workers may speak to the same patient in a given afternoon while hundreds of In the past when treatment of the soul was other patients in the same institution receive no considered as apart from medical care of the pa ,. attention. It has also come to our attention that tient; and was believed to have nothing to do with many religious workers in hospitals attempt to his health, the hospital and the physician were force their own religious views upon the patient not greatly concerned with the spiritual condition whether he desires them or not. of the patient, although some medical men have always recognized a close alliance between body It is our hope that through the following sug and soul. -

Housing Allowance and Other Clergy Tax Issues Revised December 2015

Housing Allowance and Other Clergy Tax Issues Revised December 2015 By Dennis R. Walsh, CPA This is a summary of special income tax issues applicable to clergy employed by units of government and serving in other non-traditional settings. All information provided is intended for educational purposes. As laws are constantly changing, the reader should seek competent guidance as necessary and be aware of applicable legislative, administrative, and judicial action that may have occurred since preparation of this document. Q1: When is an individual a minister for tax purposes? Whether the services of a duly ordained, licensed, or commissioned clergyperson are classified as in the “exercise of ministry” for federal tax purposes determines if tax rules unique to clergy are applicable. o For services other than as an employee of a theological seminary or church- controlled organization, in order to be considered in the exercise of ministry the services must involve either: o The ministration of sacerdotal functions (.e.g. communion, baptism, funerals, etc.), or o The conduct of religious worship The following should also be considered: o The determination of what constitutes the performance of “sacerdotal functions” and the conduct of religious worship depends on the tenets and practices of the individual’s church. Treas. Reg. § 1.1402(c)-5(b)(2)(i). o A minister who is performing the conduct of worship and ministration of sacerdotal functions is performing service in the exercise of his/her ministry, whether or not these services are performed for a religious organization. Treas. Reg. § 1.1402(c)-5(b)(2)(iii). o The service of a chaplain in the Armed Forces is considered to be those of a commissioned officer and not in the exercise of his or her ministry. -

Development and Efficacy Assessment of Equine Source Hyper-Immune Plasma Against Bacillus Anthracis

Development and Efficacy Assessment of Equine Source Hyper-Immune Plasma against Bacillus anthracis by James Marcus Caldwell A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama August 1, 2015 Keywords: horse, hyper immune plasma, Bacillus anthracis, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, toxin neutralization assay, experimental mouse B. anthracis challenge Copyright 2015 by James Marcus Caldwell Approved by Kenny Brock, Chair, Associate Dean of Biomedical Affairs Paul Walz, Professor of Pathobiology Sue Duran, Professor of Clinical Sciences Abstract The objective of the studies described here was to develop an equine source immune plasma against Bacillus anthracis and test its efficacy in two in vitro applications; as well as determine its capacity for passive protection in an infection model in mice. Initially, a safe and reliable immunization protocol for producing equine source hyper-immune plasma against B. anthracis was developed. Six Percheron horses were hyper-immunized with either the B. anthracis Sterne strain vaccine, recombinant protective antigen (rPA) homogenized with Freund’s incomplete adjuvant, or a combination of both vaccines. Multiple routes of immunization, dose (antigen mass) and immunizing antigens were explored for safety. A modified automated plasmapheresis process was then employed for the collection of plasma at a maximum target dose of up to 22 ml of plasma/kg of donor bodyweight to establish the proof-of- concept that large volumes of plasma could be safely collected from horses for large scale production of immune plasma. All three immunization protocols were found to be safe and repeatable in horses and three pheresis events were performed with the total collection of 168.36 L of plasma and a mean collection volume of 18.71 L (± 0.302 L) for each event. -

Guide to the Ovid Butler Collection Special Collections and Rare Books, Irwin Library, Butler University

Guide to the Ovid Butler Collection Special Collections and Rare Books, Irwin Library, Butler University Contact Information: Special Collections and Rare Books Irwin Library Butler University 4600 Sunset Avenue Indianapolis, Indiana 46208-3485 USA Phone: 317.940.9265 Fax: 317.940.8039 E-mail: [email protected] URL: http://www.butler.edu/library/libinfo/rare/ Summary Volume of Collection One manuscript box, one oversize folder Collection Dates 1818–1999 Provenance Butler University Restrictions None Copyright Butler University Citation Ovid Butler Collection, Special Collections and Rare Books, Irwin Library, Butler University Related Collections Board of Commissioners, letter books, 1852–60 Minutes of the Board of Commissioners, March 5, 1850–June 23, 1852 Ovid Butler letter book Ovid Butler Collection, page 2 Biographical Sketch Ovid Butler was an Indianapolis lawyer, philanthropist, and founder of North Western Christian University (today’s Butler University). Born February 7, 1801, in Augusta, New York, Butler moved with his family to Indiana in 1817. After practicing law in Shelbyville from 1825 to 1836, Butler moved to Indianapolis where he practiced law until 1849. His law partner of eleven years, Calvin Fletcher, considered himself blessed to have such a partner, and called Butler “a man of strict integrity great dilligence & integrity” (Diary of Calvin Fletcher, vol. 3, p. 198, Saturday, October 11, 1845). Although ill health led Butler to retire from his law practice in 1849, his involvement in a variety of civic causes continued. Butler was an active supporter of the antislavery movement. In 1848 he was elected as vice president of Indiana’s Free Soil Party, and backed the Free Soil Banner, a campaign paper for the party. -

Butler Alumnal Quarterly University Special Collections

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Butler Alumnal Quarterly University Special Collections 1916 Butler Alumnal Quarterly (1916) Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bualumnalquarterly Part of the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Butler University, "Butler Alumnal Quarterly (1916)" (1916). Butler Alumnal Quarterly. 6. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bualumnalquarterly/6 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Butler Alumnal Quarterly by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 5<iSsSbji2^^iS!7s^7dS7s®isSfe:S!7jiS^^ Shelf No. J « J 0, 4 i ^ Bl Accession No V^ jLsQ H" Bona Thompson Memorial BUTLER COLLEGE UBRARY K isyi r-5^ roi, jci. I'd—r^fi—Toi r^>i r»i-_f\n.J53..J3ij,a, Mumum Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/butleralumnalqua05butl 4 Butler OiiA Butl^^umnal Quarterly rOUNDERtS DAY NUMBER APRIL, 19»6 Vol. V No. 1 INDIANAPOLIS BlitlRpjJrilyePs-^]') To THE Student : Have you determined what your vocation in life will be? Do you know how desirable the profession of dentis- try is ? Would it not be well to investigate before making your final determination? Indiana Dental College has been successfully teach- ing dentistry for thirty-eight years. Our graduates are to be found in every State in the Union and nearly every foreign country. Our equipment is complete and our standing unex- celled. -

Butler Alumnal Quarterly (1915) Butler University

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Butler Alumnal Quarterly University Special Collections 1915 Butler Alumnal Quarterly (1915) Butler University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bualumnalquarterly Part of the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Butler University, "Butler Alumnal Quarterly (1915)" (1915). Butler Alumnal Quarterly. Book 5. http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bualumnalquarterly/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Butler Alumnal Quarterly by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/butleralumnalqua04butl Contents of Volume IV April, 1915 Founder's Day Address 1 Speaker Introduced by President Thomas Carr Howe 1 Education and Religion. By President George R, Grose, DePauw University 3 Chapel Talk By William Jennings Bryan 19 Conscience and Life. By Yirilliam Franklin Clarke 28 The Sheep Dog Trials at Grasmere, By Frances Elizabeth Doan..... 32 Foimder ' s Day 39 C ommencement 42 Reunion of »90 42 Oratorical Contest 43 Butler Alumnal Fund. • 43 Changed Address 43 Personal Mention 44 Births 47 Mar ri age s....... 48 Deaths 48 Our Correspondence 53 July, 1915 Commencement Address. By Charles Reynolds Brovm 55 Baccalaureate Sermon. By Jabez "Hall 70 1'Vhite Clover Blossoms. By Rachel Quick Buttz... 80 John Kuir. By Katharine kerrill Graydon 81 Napoleon on St. Helena. By Paul Wiley Weer 92 Commencement Vfeek 93 Clas s Reunions 103 New Trustees 107 A New Auditoriiam 107 Demia Butler Room 108 Recent Books 109 A Semi -Centennial Celebration 109 Honors for Butler Alumni 110 Butler College Bulletin Ill . -

Download Download

The Founding of Butler University, 1847-1855 Henry K. Shaw* Butler University at Indianapolis was the first institution of higher learning among the Christian churches (Disciples of Christ) to originate by action within the ecclesiastical structure of the denomination. Known as North Western Christian University for many years, it came into existence through the concerted effort of the Christian churches of Indiana. This religious body was fairly well established in the state by 1847, when the idea of a college was conceived. If the only known printed statistics are correct, there were some 300 churches with 19,914 members at the time. A church publication lists 130 preachers, but most of these were preach- ing laymen and not settled pastors.’ The denomination began in Indiana through the merging of dissident factions of Regular, Freewill, and German Baptist (Dunkard) congregations into the Campbell move- ment, which had its beginnings in western Virginia and northern Ohio, and the Stone movement, which had its origin primarily with former Presbyterian congregations in Ken- tucky. Since Alexander Campbell and Barton W. Stone had similar objectives and a common program and since repre- sentatives from both groups had made a declaration of formal union at Lexington, Kentucky, in 1832, it was natural that these two “frontier” religious bodies should join forces in Indiana. Stone’s followers were called Christians and their churches, Christian churches. Campbell’s followers were called Reformers and Disciples. The name “Disciples of Christ” was preferred by Campbell to designate his movement. In Indiana, churches originating from both groups took the name, “Christian churches.” There was little or no organized structure within the denomination at first, simply independent congregations hold- * Henry K. -

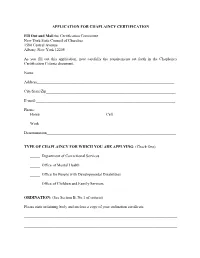

APPLICATION for CHAPLAINCY CERTIFICATION Fill out and Mail To

APPLICATION FOR CHAPLAINCY CERTIFICATION Fill Out and Mail to: Certification Committee New York State Council of Churches 1580 Central Avenue Albany, New York 12205 As you fill out this application, note carefully the requirements set forth in the Chaplaincy Certification Criteria document. Name________________________________________________________________________ Address______________________________________________________________________ City/State/Zip__________________________________________________________________ E-mail:_______________________________________________________________________ Phone: Home__________________________________Cell________________________________ Work______________________________________________________________________ Denomination__________________________________________________________________ TYPE OF CHAPLAINCY FOR WHICH YOU ARE APPLYING: (Check One) _____ Department of Correctional Services _____ Office of Mental Health _____ Office for People with Developmental Disabilities _____ Office of Children and Family Services ORDINATION: (See Section B, No.1 of criteria) Please state ordaining body and enclose a copy of your ordination certificate. ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ OFFICIAL ECCLESIASTICAL ENDORSEMENT: (Section B, No.2 of criteria) Give name of agency or official authorized by your denomination to endorse its clergy for chaplaincy positions. (This agency or person -

America's Undeclared Naval War

America's Undeclared Naval War Between September 1939 and December 1941, the United States moved from neutral to active belligerent in an undeclared naval war against Nazi Germany. During those early years the British could well have lost the Battle of the Atlantic. The undeclared war was the difference that kept Britain in the war and gave the United States time to prepare for total war. With America’s isolationism, disillusionment from its World War I experience, pacifism, and tradition of avoiding European problems, President Franklin D. Roosevelt moved cautiously to aid Britain. Historian C.L. Sulzberger wrote that the undeclared war “came about in degrees.” For Roosevelt, it was more than a policy. It was a conviction to halt an evil and a threat to civilization. As commander in chief of the U.S. armed forces, Roosevelt ordered the U.S. Navy from neutrality to undeclared war. It was a slow process as Roosevelt walked a tightrope between public opinion, the Constitution, and a declaration of war. By the fall of 1941, the U.S. Navy and the British Royal Navy were operating together as wartime naval partners. So close were their operations that as early as autumn 1939, the British 1 | P a g e Ambassador to the United States, Lord Lothian, termed it a “present unwritten and unnamed naval alliance.” The United States Navy called it an “informal arrangement.” Regardless of what America’s actions were called, the fact is the power of the United States influenced the course of the Atlantic war in 1941. The undeclared war was most intense between September and December 1941, but its origins reached back more than two years and sprang from the mind of one man and one man only—Franklin Roosevelt.