Amosqueamngstthestars.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scienza E Cultura Universitalia

SCIENZA E CULTURA UNIVERSITALIA Costantino Sigismondi (ed.) ORBE NOVUS Astronomia e Studi Gerbertiani 1 Universitalia SIGISMONDI, Costantino (a cura di) Orbe Novus / Costantino Sigismondi Roma : Universitalia, 2010 158 p. ; 24 cm. – ( Scienza e Cultura ) ISBN … 1. Storia della Scienza. Storia della Chiesa. I. Sigismondi, Costantino. 509 – SCIENZE PURE, TRATTAMENTO STORICO 270 – STORIA DELLA CHIESA In copertina: Imago Gerberti dal medagliere capitolino e scritta ORBE NOVVS nell'epitaffio tombale di Silvestro II a S. Giovanni in Laterano (entrambe le foto sono di Daniela Velestino). Collana diretta da Rosalma Salina Borello e Luca Nicotra Prima edizione: maggio 2010 Universitalia INTRODUZIONE Introduzione Costantino Sigismondi L’edizione del convegno gerbertiano del 2009, in pieno anno internazionale dell’astronomia, si è tenuta nella Basilica di S. Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri il 12 maggio, e a Seoul presso l’università Sejong l’11 giugno 2009. La scelta della Basilica è dovuta alla presenza della grande meridiana voluta dal papa Clemente XI Albani nel 1700, che ancora funziona e consente di fare misure di valore astrometrico. Il titolo di questi atti, ORBE NOVUS, è preso, come i precedenti, dall’epitaffio tombale di Silvestro II in Laterano, e vuole suggerire il legame con il “De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium” di Copernico, sebbene il contesto in cui queste parole sono tratte vuole inquadrare Gerberto nel suo ministero petrino come il nuovo pastore per tutto il mondo: UT FIERET PASTOR TOTO ORBE NOVVS. Elizabeth Cavicchi del Massachussets Institute of Technology, ha riflettuto sulle esperienze di ottica geometrica fatte da Gerberto con i tubi, nel contesto contemporaneo dello sviluppo dell’ottica nel mondo arabo con cui Gerberto era stato in contatto. -

Ihyaail Mayyit Be Fazail-E-Ahle Bayt

Imam Suyuti's ‘Ihya-Il Mayyit Be Fazaile Ahlul Bayt’ The Dead Become Alive By Grace of the Holy Five A Brief Introduction to the Author and his Book Qady Iyad relates that the Messenger of God, peace and blessings be upon him, said, “Recognition of the family of Muhammad is freedom from the Fire. Love of the family of Muhammad is crossing over the Sirat. Friendship for the family of Muhammad is safety from the Fire”. Jalaluddin Abdul Rahman Suyuti was born at Cairo and died there in 910 A.H. He travelled to various places in search of knowledge and visited Egypt, Syria, Hejaz, Yemen, India and Africa. His fields of specialization were, the exegesis of the Holy Quran, Traditions, Jurisprudence and Arabic Grammar. At the age of forty years he withdrew from public life and spent all his time writing, compiling and translating books. At the time of his death he had completed nearly 600 books on a range of subjects, including poetry. He was one of the greatest scholars of his time in Cairo, and a well-known figure among his contemporaries. In his own home-town in the district of Isyut he was considered by the people to be a holy personality having miraculous powers. He was a follower of the Shadhali Tariqa (Sufi Order) and a graduate of Al Azhar, the world’s oldest university and Sunni Islam’s foremost seat of learning. The following work of his is most definitely a most precious work and the study of it and its contents a must for all lovers of the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him and his family). -

Muhammad Umar Memon Bibliographic News

muhammad umar memon Bibliographic News Note: (R) indicates that the book is reviewed elsewhere in this issue. Abbas, Azra. ìYouíre Where Youíve Always Been.î Translated by Muhammad Umar Memon. Words Without Borders [WWB] (November 2010). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/youre-where-youve-alwaysbeen/] Abbas, Sayyid Nasim. ìKarbala as Court Case.î Translated by Richard McGill Murphy. WWB (July 2004). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/karbala-as-court-case/] Alam, Siddiq. ìTwo Old Kippers.î Translated by Muhammad Umar Memon. WWB (September 2010). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/two-old-kippers/] Alvi, Mohammad. The Wind Knocks and Other Poems. Introduction by Gopi Chand Narang. Selected by Baidar Bakht. Translated from Urdu by Baidar Bakht and Marie-Anne Erki. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 2007. 197 pp. Rs. 150. isbn 978-81-260-2523-7. Amir Khusrau. In the Bazaar of Love: The Selected Poetry of Amir Khusrau. Translated by Paul Losensky and Sunil Sharma. New Delhi: Penguin India, 2011. 224 pp. Rs. 450. isbn 9780670082360. Amjad, Amjad Islam. Shifting Sands: Poems of Love and Other Verses. Translated by Baidar Bakht and Marie Anne Erki. Lahore: Packages Limited, 2011. 603 pp. Rs. 750. isbn 9789695732274. Bedi, Rajinder Singh. ìMethun.î Translated by Muhammad Umar Memon. WWB (September 2010). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/methun/] Chughtai, Ismat. Masooma, A Novel. Translated by Tahira Naqvi. New Delhi: Women Unlimited, 2011. 152 pp. Rs. 250. isbn 978-81-88965-66-3. óó. ìOf Fists and Rubs.î Translated by Muhammad Umar Memon. WWB (Sep- tember 2010). [http://wordswithoutborders.org/article/of-fists-and-rubs/] Granta. 112 (September 2010). -

Human Hand Function This Page Intentionally Left Blank Human Hand Function

Human Hand Function This page intentionally left blank Human Hand Function Lynette A. Jones Susan J. Lederman 2006 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dares Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2006 by Lynette A. Jones and Susan J. Lederman Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrievalsystem, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jones, Lynette A. Human hand function / Lynette A. Jones and Susan J. Lederman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13 978–0–19–517315–4 ISBN 0–19–517315–5 1. Hand—Physiology. 2. Hand—Anatomy. 3. Hand—Movements. I. Lederman, Susan J. II. Title. [DNLM: 1. Hand—physiology. 2. Hand—anatomy & history. WE 830J775h 2006] QP334.J66 2006 611'.97—dc22 2005018742 987654321 To all those who have worked to unravel the mysteries of the human hand This page intentionally left blank ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The ideas and initialplanning for this book began in September 2001 during Susan Lederman's sabbaticalin the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. -

His Music Touched Millions Partab Ramchand

REAR WINDOW JIM REEVES His music touched millions Partab Ramchand or innumerable Western were almost always emotional. music fans in India their He has either lost the girl he Fidea of nirvana or total loved, or is a victim of unrequited bliss is to close their eyes and love and has been unjustly treated listen to the velvety voice of by the girl who has ditched him. Jim Reeves. His 54th death It would appear that there is a lot anniversary falls on 31 July and of melancholy in Reeves’ songs, his 95th birth anniversary on 20 but he was able to convey the August, and as such it is a good hurt through his rich baritone time to remember the singer and apt usage of words. In his whose voice and words have numbers the music stays in touched millions of lives around the background; it is the voice the world. Among the many and words that are of utmost countries in which “Gentleman importance. Jim” was popular, India and Sri Jim Reeves Lanka rank very high. Outside of In India, Reeves continues to enjoy the US where he was born, Reeves immense popularity more than half was not complete without numerous a century after his death. Among the enjoys unprecedented popularity in requests for a Jim Reeves song. South Africa among Western singers; Anglo-Indian community there is no it would not be wrong to say that In Madras I have attended numerous function or event that does not feature India and Sri Lanka are perhaps “Jim Reeves Nite’s” over the years, a song or two by Reeves, and the next on the list. -

Steward : 75 Years of Alberta Energy Regulation / the Sans Serif Is Itc Legacy Sans, Designed by Gordon Jaremko

75 years of alb e rta e ne rgy re gulation by gordon jaremko energy resources conservation board copyright © 2013 energy resources conservation board Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication ¶ This book was set in itc Berkeley Old Style, designed by Frederic W. Goudy in 1938 and Jaremko, Gordon reproduced in digital form by Tony Stan in 1983. Steward : 75 years of Alberta energy regulation / The sans serif is itc Legacy Sans, designed by Gordon Jaremko. Ronald Arnholm in 1992. The display face is Albertan, which was originally cut in metal at isbn 978-0-9918734-0-1 (pbk.) the 16 point size by Canadian designer Jim Rimmer. isbn 978-0-9918734-2-5 (bound) It was printed and bound in Edmonton, Alberta, isbn 978-0-9918734-1-8 (pdf) by McCallum Printing Group Inc. 1. Alberta. Energy Resources Conservation Board. Book design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design. 2. Alberta. Energy Resources Conservation Board — History. 3. Energy development — Government policy — Alberta. 4. Energy development — Law and legislation — Alberta. 5. Energy industries — Law and legislation — Alberta. i. Alberta. Energy Resources Conservation Board. ii. Title. iii. Title: 75 years of Alberta energy regulation. iv. Title: Seventy-five years of Alberta energy regulation. hd9574 c23 a4 j37 2013 354.4’528097123 c2013-980015-8 con t e nt s one Mandate 1 two Conservation 23 three Safety 57 four Environment 77 five Peacemaker 97 six Mentor 125 epilogue Born Again, Bigger 147 appendices Chairs 154 Chronology 157 Statistics 173 INSPIRING BEGINNING Rocky Mountain vistas provided a dramatic setting for Alberta’s first oil well in 1902, at Cameron Creek, 220 kilometres south of Calgary. -

International Review of Environmental History: Volume 5, Issue 1, 2019

TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction James Beattie 1 Nature’s revenge: War on the wilderness during the opening of Brazil’s ‘Last Western Frontier’ Sandro Dutra e Silva 5 Water as the ultimate sink: Linking fresh and saltwater history Simone M. Müller and David Stradling 23 Climate change: Debate and reality Daniel R. Headrick 43 Biofuels’ unbalanced equations: Misleading statistics, networked knowledge and measured parameters Kate B. Showers 61 ‘To get a cargo of flesh, bone, and blood’: Animals in the slave trade in West Africa Christopher Blakley 85 Providing guideline principles: Botany and ecology within the State Forest Service of New Zealand during the 1920s Anton Sveding 113 ‘Zambesi seeds from Mr Moffat’: Sir George Grey as imperial botanist John O’Leary 129 INTRODUCTION JAMES BEATTIE Victoria University of Wellington; Research Associate Centre for Environmental History The Australian National University; Senior Research Associate Faculty of Humanities, University of Johannesburg This first issue of 2019 speaks to the many exciting dimensions of environmental history. Represented here is environmental history’s great breadth, in terms of geographical scope (Brazil, the Atlantic world, Europe, global, Africa and New Zealand); topics (animal studies, biography, climatological analysis, energy and waste); and temporal span (from the early modern to the contemporary period). The first article, ‘Nature’s revenge: War on the wilderness during the opening of Brazil’s “Last Western Frontier”’, explores the ongoing trope of the frontier and ‘frontiersman’ in the environmental history of twentieth-century Amazonia, Brazil. The author, Sandro Dutra e Silva, does so by skilfully analysing the creation of the heroic image of the road-building engineer Bernardo Sayão, and his deployment by the state to underpin its aims of developing Amazonia. -

Aerospace Dimensions Leader's Guide

Leader Guide www.capmembers.com/ae Leader Guide for Aerospace Dimensions 2011 Published by National Headquarters Civil Air Patrol Aerospace Education Maxwell AFB, Alabama 3 LEADER GUIDES for AEROSPACE DIMENSIONS INTRODUCTION A Leader Guide has been provided for every lesson in each of the Aerospace Dimensions’ modules. These guides suggest possible ways of presenting the aerospace material and are for the leader’s use. Whether you are a classroom teacher or an Aerospace Education Officer leading the CAP squadron, how you use these guides is up to you. You may know of different and better methods for presenting the Aerospace Dimensions’ lessons, so please don’t hesitate to teach the lesson in a manner that works best for you. However, please consider covering the lesson outcomes since they represent important knowledge we would like the students and cadets to possess after they have finished the lesson. Aerospace Dimensions encourages hands-on participation, and we have included several hands-on activities with each of the modules. We hope you will consider allowing your students or cadets to participate in some of these educational activities. These activities will reinforce your lessons and help you accomplish your lesson out- comes. Additionally, the activities are fun and will encourage teamwork and participation among the students and cadets. Many of the hands-on activities are inexpensive to use and the materials are easy to acquire. The length of time needed to perform the activities varies from 15 minutes to 60 minutes or more. Depending on how much time you have for an activity, you should be able to find an activity that fits your schedule. -

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-JO-100-18-CA-004 Weekly Report 209-212 — October 1–31, 2018 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, Darren Ashby, Kyra Kaercher, Gwendolyn Kristy Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports: Syria 5 Heritage Timeline 72 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points ● Aleppo Governorate ○ Cleaning efforts have begun at the National Museum of Aleppo in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Heritage Response Report SHI 18-0130 ○ Illegal excavations were reported at Shash Hamdan, a Roman tomb in Manbij, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0124 ○ Illegal excavation continues at the archaeological site of Cyrrhus in Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0090 UPDATE ● Deir ez-Zor Governorate ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sayyidat Aisha Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0118 ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sultan Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0119 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike destroyed Ammar bin Yasser Mosque in Albu-Badran Neighborhood, al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0121 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike damaged al-Aziz Mosque in al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. -

Song List - by Song - Mr K Entertainment

Main Song List - By Song - Mr K Entertainment Title Artist Disc Track 02:00:00 AM Iron Maiden 1700 5 3 AM Matchbox 20 236 8 4:00 AM Our Lady Peace 1085 11 5:15 Who, The 167 9 3 Spears, Britney 1400 2 7 Prince & The New Power Generation 1166 11 11 Pope, Cassadee 1657 4 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed 803 12 22 Allen, Lily 1413 3 22 Swift, Taylor 1646 15 23 Mike Will Made It & Miley Cyrus 1667 16 33 Smashing Pumpkins 1662 11 45 Shinedown 1190 19 98.6 Keith 1096 4 99 Toto 1150 20 409 Beach Boys, The 989 7 911 Jean, Wyclef & Mary J. Blige 725 4 1215 Strokes 1685 12 1234 Feist 1125 12 1929 Deana Carter 1636 15 1959 Anderson, John 1416 7 1963 New Order 1313 1 1969 Stegall, Keith 1004 13 1973 Blunt, James 1294 16 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 820 4 1982 Estefan, Gloria 153 1 1982 Travis, Randy 367 5 1983 Neon Trees 1522 14 1984 Bowie, David 1455 14 1985 Bowling For Soup 670 5 1994 Aldean, Jason 1647 15 1999 Prince 182 9 Dec-43 Montgomery, John Michael 1715 4 1-2-3 Berry, Len 46 13 # Dream Lennon, John 1154 3 #1 Crush Garbage 215 12 #Selfie Chainsmokers 1666 6 Check Us Out Online at: www.AustinKaraoke.com Main Song List - By Song - Mr K Entertainment (I Know) I'm Losing You Temptations 1199 5 (Love Is Like A) Heatwave Reeves, Martha And The Vandellas 1199 6 (Your(The Angels Love Keeps Wanna Lifting Wear Me) My) Higher Red Shoes And Costello, Elvis 1209 4 Higher Wilson, Jackie 1199 8 (You're My) Soul & Inspiration Righteous Brothers 963 7 (You're) Adorable Martin, Dean 1375 11 1 2 3 4 Feist 939 14 1 Luv E40 & Leviti 1499 9 1, 2 Step Ciara & Missy Elliott 746 5 1, 2, 3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Warfare in a Fragile World: Military Impact on the Human Environment

Recent Slprt•• books World Armaments and Disarmament: SIPRI Yearbook 1979 World Armaments and Disarmament: SIPRI Yearbooks 1968-1979, Cumulative Index Nuclear Energy and Nuclear Weapon Proliferation Other related •• 8lprt books Ecological Consequences of the Second Ihdochina War Weapons of Mass Destruction and the Environment Publish~d on behalf of SIPRI by Taylor & Francis Ltd 10-14 Macklin Street London WC2B 5NF Distributed in the USA by Crane, Russak & Company Inc 3 East 44th Street New York NY 10017 USA and in Scandinavia by Almqvist & WikseH International PO Box 62 S-101 20 Stockholm Sweden For a complete list of SIPRI publications write to SIPRI Sveavagen 166 , S-113 46 Stockholm Sweden Stoekholol International Peace Research Institute Warfare in a Fragile World Military Impact onthe Human Environment Stockholm International Peace Research Institute SIPRI is an independent institute for research into problems of peace and conflict, especially those of disarmament and arms regulation. It was established in 1966 to commemorate Sweden's 150 years of unbroken peace. The Institute is financed by the Swedish Parliament. The staff, the Governing Board and the Scientific Council are international. As a consultative body, the Scientific Council is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. Governing Board Dr Rolf Bjornerstedt, Chairman (Sweden) Professor Robert Neild, Vice-Chairman (United Kingdom) Mr Tim Greve (Norway) Academician Ivan M£ilek (Czechoslovakia) Professor Leo Mates (Yugoslavia) Professor -

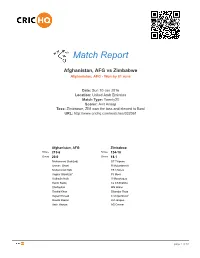

Match Report

Match Report Afghanistan, AFG vs Zimbabwe Afghanistan, AFG - Won by 81 runs Date: Sun 10 Jan 2016 Location: United Arab Emirates Match Type: Twenty20 Scorer: Anit Anoop Toss: Zimbabwe, ZIM won the toss and elected to Bowl URL: http://www.crichq.com/matches/332061 Afghanistan, AFG Zimbabwe Score 215-6 Score 134-10 Overs 20.0 Overs 18.1 Mohammad Shahzad† DT Tiripano Usman Ghani R Mutumbami† Mohammad Nabi TS Chisoro Asghar Stanikzai* PJ Moor Gulbadin Naib H Masakadza Karim Sadiq CJ Chibhabha Shafiqullah MN Waller Rashid Khan Sikandar Raza Sayed Shirzad E Chigumbura* Dawlat Zadran LM Jongwe Amir Hamza AG Cremer page 1 of 34 Scorecards 1st Innings | Batting: Afghanistan, AFG R B 4's 6's SR Mohammad . 1 1 . 6 1 4 2 . 1 . 4 . 1 . 1 4 . 4 1 4 . 1 6 4 4 1 1 . 1 . 6 1 not out 118 67 10 8 176.12 6 6 1 6 4 . 1 6 . 6 1 2 1 1 . 4 1 1 . 1 4 2 1 2 . 1 Shahzad† Usman Ghani 1 . 2 1 1 . // b AG Cremer 5 13 0 0 38.46 Asghar . 1 . 6 1 1 1 . 4 4 . // b LM Jongwe 18 12 2 1 150.0 Stanikzai* Karim Sadiq 2 4 2 4 . // c PJ Moor b TS Chisoro 12 5 2 0 240.0 Shafiqullah . 1 6 1 . // c PJ Moor b CJ Chibhabha 8 6 0 1 133.33 Mohammad 1 1 . 6 2 1 1 . 4 6 . // b DT Tiripano 22 12 1 2 183.33 Nabi Gulbadin Naib 1 6 2 1 2 1 // run out (DT Tiripano/R Mutumbami†) 13 6 0 1 216.67 Extras (w 6, nb 1, b 8, lb 4) 19 Total (6 wickets; 20.0 overs) 215 10.75 RPO Did Not Bat:["Rashid Khan", "Sayed Shirzad", "Dawlat Zadran", "Amir Hamza"] Fall of Wicket: 43-1 (Usman Ghani 6.1 ov ), 116-2 (Asghar Stanikzai 11.4 ov ), 145-3 (Karim Sadiq 13.3 ov ), 154-4 (Shafiqullah 14.4 ov ), 201-5 (Mohammad Nabi 18.5 ov ), 215-6 (Gulbadin Naib 19.6 ov ) Bowling: Zimbabwe, ZIM O M R W EC AV EX DT Tiripano 4.0 0 36 1 9.00 36.00 (w 3) TS Chisoro 4.0 0 25 1 6.25 25.00 (w 1) LM Jongwe 4.0 0 34 1 8.50 34.00 (w 1) CJ Chibhabha 4.0 0 56 1 14.00 56.00 AG Cremer 3.0 0 35 1 11.67 35.00 (w 1) Sikandar Raza 1.0 0 17 0 17.00 - (nb 1) Notes: 50 up for Afghanistan at 7.1.