Kathryn Suzannah Beresford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odo, Bishop of Bayeux and Earl of Kent

( 55 ) ODO, BISHOP OF BAYEUX AND EARL OF KENT. BY SER REGINALD TOWER, K.C.M.G., C.Y.O. IN the volumes of Archceologia Cantiana there occur numerous references to Bishop Odo, half-brother of William the Conqueror ; and his name finds frequent mention in Hasted's History of Kent, chiefly in connection with the lands he possessed. Further, throughout the records of the early Norman chroniclers, the Bishop of Bayeux is constantly cited among the outstanding figures in the reigns of William the Conqueror and of his successor William Rufus, as well as in the Duchy of Normandy. It seems therefore strange that there should be (as I am given to understand) no Life of the Bishop beyond the article in the Dictionary of National Biography. In the following notes I have attempted to collate available data from contemporary writers, aided by later historians of the period during, and subsequent to, the Norman Conquest. Odo of Bayeux was the son of Herluin of Conteville and Herleva (Arlette), daughter of Eulbert the tanner of Falaise. Herleva had .previously given birth to William the Conqueror by Duke Robert of Normandy. Odo's younger brother was Robert, Earl of Morton (Mortain). Odo was born about 1036, and brought up at the Court of Normandy. In early youth, about 1049, when he was attending the Council of Rheims, his half-brother, William, bestowed on him the Bishopric of Bayeux. He was present, in 1066, at the Conference summoned at Lillebonne, by Duke William after receipt of the news of Harold's succession to the throne of England. -

Black House Farm, Hinton Ampner, Hampshire February 2018

Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment in Advance of the Proposed development of Land at Black House Farm, Hinton Ampner, Hampshire February 2018 Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment in Advance of the Proposed development of land at Black House Farm, Hinton Ampner, Hampshire. Report for Nadim Khatter Date of Report: 20th February 2018 SWAT ARCHAEOLOGY Swale and Thames Archaeological Survey Company School Farm Oast, Graveney Road Faversham, Kent ME13 8UP Tel; 01795 532548 or 07885 700 112 www.swatarchaeology.co.uk Black House Farm, Hinton Ampner, Hampshire Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment Contents 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Project Background ......................................................................................... 4 1.2 The Site ............................................................................................................ 4 1.3 The Proposed Development............................................................................ 4 1.4 Project Constraints .......................................................................................... 5 1.5 Scope of Document ......................................................................................... 5 2 PLANNING BACKGROUND .................................................................................................. 5 2.1 Introduction..................................................................................................... 5 2.2 -

First Floor, St Georges Chambers, St Georges Street, Winchester, Hampshire So23 8Aj

FIRST FLOOR, ST GEORGES CHAMBERS, ST GEORGES STREET, WINCHESTER, HAMPSHIRE SO23 8AJ FULLY FITTED OFFICE SPACE - TO LET KEY FEATURES • First floor office accommodation • Fully fitted space • Kitchen facilities • Fully refurbished throughout • Flexible term available • Air conditioning T: 023 8082 0900 vailwilliams.com 1,388 sq ft (128.93 sq m) NIA FIRST FLOOR, ST GEORGES CHAMBERS, ST GEORGES STREET, WINCHESTER, HAMPSHIRE SO23 8AJ LOCATION St Georges Chambers is located in the heart of the affluent Cathedral city of Winchester, with excellent road and rail communications via Winchester Train Station and the M3 motorway. Winchester is a vibrant commercial hub for the region. In addition to the Hampshire County Council headquarters and the Crown Court, business occupiers with headquarters in Winchester include Rathbones Investment Management, Denplan and Arqiva. The building is positioned at the intersection of Jewry Street and the prime retail high street, with the ground and part first floor occupied by Barclays Bank. T: 023 8082 0900 vailwilliams.com FIRST FLOOR, ST GEORGES CHAMBERS, ST GEORGES STREET, WINCHESTER, HAMPSHIRE SO23 8AJ DESCRIPTION TERM This impressive 4 storey property is a landmark building in the heart The property is available by way of an assignment of the existing of the city, built on the site for the former George hotel. The ground lease to Avask Accounting at an all-inclusive rent of £34,080 per and first floor have been occupied by Barclays Bank since completion annum, exclusive of VAT. in 1959. The remaining space at first, second and third floor level has more recently been converted to Grade A offices with occupiers Alternatively, the offices are available to let on terms to be agreed. -

Coast Path Makes Progress in Essex and Kent

walkerSOUTH EAST No. 99 September 2017 Coast path makes progress in Essex and Kent rogress on developing coast path in Kent with a number the England Coast Path of potentially contentious issues Pnational trail in Essex and to be addressed, especially around Kent has continued with Natural Faversham. If necessary, Ian England conducting further will attend any public hearings route consultations this summer. Ramblers volunteers have been or inquiries to defend the route very involved with the project proposed by Natural England. from the beginning, surveying Consultation on this section closed routes and providing input to on 16 August. proposals. The trail, scheduled Meanwhile I have started work to be completed in 2020, will run on the second part of the Area's for about 2,795 miles/4.500km. guide to the Kent Coast Path which is planned to cover the route from Kent Ramsgate to Gravesend (or possibly It is now over a year since the section of the England Coast Path further upriver). I've got as far as from Camber to Ramsgate opened Reculver, site of both a Roman fort in July 2016. Since then work has and the remains of a 12th century been underway to extend the route church whose twin towers have long in an anti-clockwise direction. been a landmark for shipping. On The route of the next section from the way I have passed delightful Ramsgate to Whitstable has been beaches and limestone coves as well determined by the Secretary of as sea stacks at Botany Bay and the State but the signage and the works Turner Contemporary art gallery at necessary to create a new path along Margate. -

Allington Castle Conway

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society \ u"*_; <Ak_CL <&__•_ •E!**?f*K- TOff*^ ^ i if •P%% —5** **•"'. • . " ft - . if • i ' _! ' ' •_• .' |• > ' V ''% .; fl y H H i Pko^o.l ALLINGTON CASTLE (A): GENERAL VIEW FROM E. [W. ff.-B. ( 337 ) ALLINGTON CASTLE. BY SIR W. MARTIN CONWAY, M.A., E.S.A. THE immediate neighbourhood of Allington Castle appears to have been a very ancient site of human habitation. It lies close to what must have been an important ford over the Medway, at a point which was approximately the head of low-tide navigation. The road from the east, which debouches on the right bank of the river close beside the present Malta Inn, led straight to the ford, and its continua- tion on the other bank can be traced as a deep furrow through the Lock Wood, and almost as far as the church, though in part it has recently been obliterated by the dejection of quarry debris. This ancient road may be traced up to the Pilgrims' Way, from which it branched off. In the neighbourhood of the castle, at points not exactly recorded, late Celtic burials have been discovered containing remains of the Aylesford type. Where there were burials there was no doubt a settlement. In Roman days the site was likewise well occupied, and the buried ruins of a Roman villa are marked on the ordnance map in the field west of the castle. The site seems to be indicated by a level place on the sloping hill, and when the land in question falls into my hands I propose to make the researches necessary to reveal the situation and character of the villa. -

The Construction of Northumberland House and the Patronage of Its Original Builder, Lord Henry Howard, 1603–14

The Antiquaries Journal, 90, 2010,pp1 of 60 r The Society of Antiquaries of London, 2010 doi:10.1017⁄s0003581510000016 THE CONSTRUCTION OF NORTHUMBERLAND HOUSE AND THE PATRONAGE OF ITS ORIGINAL BUILDER, LORD HENRY HOWARD, 1603–14 Manolo Guerci Manolo Guerci, Kent School of Architecture, University of Kent, Marlowe Building, Canterbury CT27NR, UK. E-mail: [email protected] This paper affords a complete analysis of the construction of the original Northampton (later Northumberland) House in the Strand (demolished in 1874), which has never been fully investigated. It begins with an examination of the little-known architectural patronage of its builder, Lord Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton from 1603, one of the most interesting figures of the early Stuart era. With reference to the building of the contemporary Salisbury House by Sir Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, the only other Strand palace to be built in the early seventeenth century, textual and visual evidence are closely investigated. A rediscovered eleva- tional drawing of the original front of Northampton House is also discussed. By associating it with other sources, such as the first inventory of the house (transcribed in the Appendix), the inside and outside of Northampton House as Henry Howard left it in 1614 are re-configured for the first time. Northumberland House was the greatest representative of the old aristocratic mansions on the Strand – the almost uninterrupted series of waterfront palaces and large gardens that stretched from Westminster to the City of London, the political and economic centres of the country, respectively. Northumberland House was also the only one to have survived into the age of photography. -

Edward Hasted the History and Topographical Survey of the County

Edward Hasted The history and topographical survey of the county of Kent, second edition, volume 6 Canterbury 1798 <i> THE HISTORY AND TOPOGRAPHICAL SURVEY OF THE COUNTY OF KENT. CONTAINING THE ANTIENT AND PRESENT STATE OF IT, CIVIL AND ECCLESIASTICAL; COLLECTED FROM PUBLIC RECORDS, AND OTHER AUTHORITIES: ILLUSTRATED WITH MAPS, VIEWS, ANTIQUITIES, &c. THE SECOND EDITION, IMPROVED, CORRECTED, AND CONTINUED TO THE PRESENT TIME. By EDWARD HASTED, Esq. F. R. S. and S. A. LATE OF CANTERBURY. Ex his omnibus, longe sunt humanissimi qui Cantium incolunt. Fortes creantur fortibus et bonis, Nec imbellem feroces progenerant. VOLUME VI. CANTERBURY PRINTED BY W. BRISTOW, ON THE PARADE. M.DCC.XCVIII. <ii> <blank> <iii> TO THOMAS ASTLE, ESQ. F. R. S. AND F. S. A. ONE OF THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM, KEEPER OF THE RECORDS IN THE TOWER, &c. &c. SIR, THOUGH it is certainly a presumption in me to offer this Volume to your notice, yet the many years I have been in the habit of friendship with you, as= sures me, that you will receive it, not for the worth of it, but as a mark of my grateful respect and esteem, and the more so I hope, as to you I am indebted for my first rudiments of antiquarian learning. You, Sir, first taught me those rudiments, and to your kind auspices since, I owe all I have attained to in them; for your eminence in the republic of letters, so long iv established by your justly esteemed and learned pub= lications, is such, as few have equalled, and none have surpassed; your distinguished knowledge in the va= rious records of the History of this County, as well as of the diplomatique papers of the State, has justly entitled you, through his Majesty’s judicious choice, in preference to all others, to preside over the reposi= tories, where those archives are kept, which during the time you have been entrusted with them, you have filled to the universal benefit and satisfaction of every one. -

Ashley Walsh

Civil religion in Britain, 1707 – c. 1800 Ashley James Walsh Downing College July 2017 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. All dates have been presented in the New Style. 1 Acknowledgements My greatest debt is to my supervisor, Mark Goldie. He encouraged me to study civil religion; I hope my performance vindicates his decision. I thank Sylvana Tomaselli for acting as my adviser. I am also grateful to John Robertson and Brian Young for serving as my examiners. My partner, Richard Johnson, and my parents, Maria Higgins and Anthony Walsh, deserve my deepest gratitude. My dear friend, George Owers, shared his appreciation of eighteenth- century history over many, many pints. He also read the entire manuscript. -

The Country House in English Women's Poetry 1650-1750: Genre, Power and Identity

The country house in English women's poetry 1650-1750: genre, power and identity Sharon L. Young A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the University’s requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 University of Worcester Abstract The country house in English women’s poetry 1650-1750: power, identity and genre This thesis examines the depiction of the country estate in English women’s poetry, 1650-1750. The poems discussed belong to the country house genre, work with or adapt its conventions and tropes, or belong to what may be categorised as sub-genres of the country house poem. The country house estate was the power base of the early modern world, authorizing social status, validating political power and providing an economic dominance for the ruling elite. This thesis argues that the depiction of the country estate was especially pertinent for a range of female poets. Despite the suggestive scholarship on landscape and place and the emerging field of early modern women’s literary studies and an extensive body of critical work on the country house poem, there have been to date no substantial accounts of the role of the country estate in women’s verse of this period. In response, this thesis has three main aims. Firstly, to map out the contours of women’s country house poetry – taking full account of the chronological scope, thematic and formal diversity of the texts, and the social and geographic range of the poets using the genre. Secondly, to interrogate the formal and thematic characteristics of women’s country house poetry, looking at the appropriation and adaptation of the genre. -

Fact Service Issue 10

FACT SERVICE 37 Gender pay gap across EU member states 39 NHS members' links to private healthcare Factory output up, but below pre-crisis peak 38 Poor mental health of 'blue light' staff 40 Mergers and takeovers at record low Pay and expenses for top university job Jobs growth for women is in low-paid jobs Annual Subscription £84.50 (£71.50 for LRD affiliates) Volume 77, Issue 10, 12 March 2015 the Czech Republic and Malta (both -4.1 pp) and Gender pay gap across Cyprus (-3.7 pp). In contrast, the gender pay gap has risen between EU member states 2008 and 2013 in nine EU states, with the most sig- The UK had the sixth widest gender pay gap nificant increases seen in Portugal (from 9.2% in across the 28 European Union (EU) member states 2008 to 13.0% in 2013, or +3.8 pp), Spain (+3.2 pp), in 2013. Latvia (+2.6 pp), Italy (+2.4 pp) and Estonia (+2.3 pp). Eurostat’s gender pay gap represents the dif- ference between average gross hourly earnings Figures released by Eurostat on International Wom- of male paid employees and of female paid em- en’s Day put the UK gender pay gap at 19.7%, while ployees as a percentage of average gross hourly the widest gap was in Estonia with a 29.9% gap. The earnings of male paid employees. other four countries with wider pay gaps than the UK were: Austria (23.0%), Czech Republic (22.1%), Germany (21.6%) and Slovakia (19.8%). -

And the Penenden Heath Meeting, 1828

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society THE 'MEN OF KENT' AND THE PENENDEN HEATH MEETING, 1828 KATHRYN BERESFORD In recent years much historical debate has centred on questions of identity, a reflection of the tensions and uncertainties in contemporary society. National, gender and ethnic identities, for example, have all come under scrutiny. A feature of recent work by historians of the nineteenth century has been to highlight the subjectivity of such identities, dependent as they were on momentary reactions, shifting political alliances and the sheer transient nature of what conduct, appearance or belief was held to be 'English', 'masculine' or any such other categorisation at any particular moment.1 An era of interest has been the late 1820s and 1830s, a period which encompassed the passing of the Catholic Emancipation Act in 1829, and the Great Reform Act in 1832, the first of the three acts of the nineteenth century that widened the (male) franchise. During these years, what it was to be a citizen, to hold a stake in the government of Britain and the Empire, was hotly debated in provincial and metropolitan societies, meetings and newspapers, as well as in the formal arena of Parliament. Political claims made by hugely diverse groups and individuals, from conservative anti-Catholic agitators to radical reformers, were framed in the language of 'Englishmen' or 'Britons', categories that implied a sense of national belonging and a right to political agency for those who wielded them. At the same moments, such notions were defined against those who could not, or would not, be established as such: 'other' groups such as women, Catholics, the colonised people of the Empire, or merely their political rivals who, inevitably, were far less 'manly' or 'English'! However, the language of 'Englishness' and English identities was not generic. -

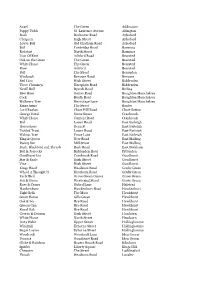

Draught Copy Distribution List

Angel The Green Addington Poppy Fields St. Laurence Avenue Allington Bush Rochester Road Aylesford Chequers High Street Aylesford Lower Bell Old Chatham Road Aylesford Bull Tonbridge Road Barming Redstart North Street Barming Lion Of Kent Ashford Road Bearsted Oak on the Green The Green Bearsted White Horse The Green Bearsted Rose Ashford Bearsted Bull The Street Benenden Woolpack Benover Road Benover Red Lion High Street Biddenden Three Chimneys Hareplain Road Biddenden Nevill Bull Ryarsh Road Birling Beer Barn Sutton Road Boughton Monchelsea Cock Heath Road Boughton Monchelsea Mulberry Tree Hermitage Lane Boughton Monchelsea Kings Arms The Street Boxley Lord Raglan Chart Hill Road Chart Sutton George Hotel Stone Street Cranbrook White Horse Carriers Road Cranbrook Bull Lower Road East Farleigh Horseshoes Dean St East Farleigh Tickled Trout Lower Road East Farleigh Walnut Tree Forge Lane East Farleigh King & Queen New Road East Malling Rising Sun Mill Street East Malling Bush, Blackbird and Thrush Bush Road East Peckham Bell & Jorrocks Biddenden Road Frttenden Goudhurst Inn Cranbrook Road Goudhurst Star & Eagle High Street Goudhurst Vine High Street Goudhurst Kings Head Headcorn Road Grafty Green Who'd A Thought It Headcorn Road Grafty Green Early Bird Grove Green Centre Grove Green Fox & Goose Weavering Street Grove Green Rose & Crown Otford Lane Halstead Hawkenbury Hawkenbury Road Hawkenbury Eight Bells The Moor Hawkhurst Great House Gills Green Hawkhurst Oak & Ivy Rye Road Hawkhurst Queens Inn Rye Road Hawkhurst Royal Oak Rye Road