In This Issue . . . Michael Whelan Merry M. Merryfield Preparing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Sunday 31St August 2003

The World Science Fiction Society Minutes of the Business Meeting at Torcon 3 th Friday 29 to Sunday 31st August 2003 Introduction………………………………………………………………….… 3 Preliminary Business Meeting, Friday……………………………………… 4 Main Business Meeting, Saturday…………………………………………… 11 Main Business Meeting, Sunday……………………………………………… 16 Preliminary Business Meeting Agenda, Friday………………………………. 21 Report of the WSFS Nitpicking and Flyspecking Committee 27 FOLLE Report 33 LA con III Financial Report 48 LoneStarCon II Financial Report 50 BucConeer Financial Report 51 Chicon 2000 Financial Report 52 The Millennium Philcon Financial Report 53 ConJosé Financial Report 54 Torcon 3 Financial Report 59 Noreascon 4 Financial Report 62 Interaction Financial Report 63 WSFS Business Meeting Procedures 65 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Saturday…………………………………...... 69 Report of the Mark Protection Committee 73 ConAdian Financial Report 77 Aussiecon Three Financial Report 78 Main Business Meeting Agenda, Sunday………………………….................... 79 Time Travel Worldcon Report………………………………………………… 81 Response to the Time Travel Worldcon Report, from the 1939 World Science Fiction Convention…………………………… 82 WSFS Constitution, with amendments ratified at Torcon 3……...……………. 83 Standing Rules ……………………………………………………………….. 96 Proposed Agenda for Noreascon 4, including Business Passed On from Torcon 3…….……………………………………… 100 Site Selection Report………………………………………………………… 106 Attendance List ………………………………………………………………. 109 Resolutions and Rulings of Continuing Effect………………………………… 111 Mark Protection Committee Members………………………………………… 121 Introduction All three meetings were held in the Ontario Room of the Fairmont Royal York Hotel. The head table officers were: Chair: Kevin Standlee Deputy Chair / P.O: Donald Eastlake III Secretary: Pat McMurray Timekeeper: Clint Budd Tech Support: William J Keaton, Glenn Glazer [Secretary: The debates in these minutes are not word for word accurate, but every attempt has been made to represent the sense of the arguments made. -

Rogerzelazny

the collected $29 stories of “ Roger Zelazny was one of the collected stories of roger the collected stories of SF’s finest storytellers, a zelazny Roger Zelazny poet with an immense and Roger Zelazny 5 volume 5: nine black doves instinctive gift for language. volume five nine black Reading Zelazny is like doves nine black doves WINN Roger Zelazny wrote with a lyrical quality rarely found G dropping into a Mozart in science fiction—creating rousing adventures, intricate H © BETH “what-if?” stories, clever situations, and sweeping vistas in P string quartet as played which to play them out. Leavened with layers of allusion by Thelonious Monk.” PHOTOGRA and imagery, his diverse writing styles and breadth of — GREG BEAR subject matter brought him praise as a prose poet and a Roger Zelazny (1937–1995) reaffirmed his mastery of short Renaissance man. Zelazny’s vivid stories, especially his fiction during the 1980s with his release of a pair of Hugo-winning stories, his completion of the Dilvish series, and his creation of Volume 5: Nine Black Doves covers spectacular novellas, are classics in the field. Croyd Crenson for the Wild Cards shared world. the 1980s, when Zelazny’s mature Although he is best known for his 10-volume Amber During the interval covered by this volume, Zelazny began the second craft produced the Hugo-winning and series, his early novels Lord of Light and Creatures of Light five-book series in the Chronicles of Amber, starting with Trumps of Doom. He continued his serious study of martial arts and he created Nebula-nominated stories, “24 Views of and Darkness, and the Dilvish series, his shorter works a shared world of his own. -

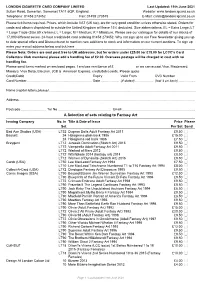

LCCC Thematic List

LONDON CIGARETTE CARD COMPANY LIMITED Last Updated: 11th June 2021 Sutton Road, Somerton, Somerset TA11 6QP, England. Website: www.londoncigcard.co.uk Telephone: 01458 273452 Fax: 01458 273515 E-Mail: [email protected] Please tick items required. Prices, which include VAT (UK tax), are for very good condition unless otherwise stated. Orders for cards and albums dispatched to outside the United Kingdom will have 15% deducted. Size abbreviations: EL = Extra Large; LT = Large Trade (Size 89 x 64mm); L = Large; M = Medium; K = Miniature. Please see our catalogue for details of our stocks of 17,000 different series. 24-hour credit/debit card ordering 01458 273452. Why not sign up to our Free Newsletter giving you up to date special offers and Discounts not to mention new additions to stock and information on our current auctions. To sign up enter your e-mail address below and tick here _____ Please Note: Orders are sent post free to UK addresses, but for orders under £25.00 (or £15.00 for LCCC's Card Collectors Club members) please add a handling fee of £2.00. Overseas postage will be charged at cost with no handling fee. Please send items marked on enclosed pages. I enclose remittance of £ or we can accept Visa, Mastercard, Maestro, Visa Delta, Electron, JCB & American Express, credit/debit cards. Please quote Credit/Debit Expiry Valid From CVC Number Card Number...................................................................... Date .................... (if stated).................... (last 3 on back) .................. Name (capital -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items DC COLLECTING THE MULTIVERSE On our Cover The Art of Sideshow By Andrew Farago. Recommended. MASTERPIECES OF FANTASY ART Delve into DC Comics figures and Our Highest Recom- sculptures with this deluxe book, mendation. By Dian which features insights from legendary Hanson. Art by Frazetta, artists and eye-popping photography. Boris, Whelan, Jones, Sideshow is world famous for bringing Hildebrandt, Giger, DC Comics characters to life through Whelan, Matthews et remarkably realistic figures and highly al. This monster-sized expressive sculptures. From Batman and Wonder Woman to The tome features original Joker and Harley Quinn...key artists tell the story behind each paintings, contextualized extraordinary piece, revealing the design decisions and expert by preparatory sketches, sculpting required to make the DC multiverse--from comics, film, sculptures, calen- television, video games, and beyond--into a reality. dars, magazines, and Insight Editions, 2020. paperback books for an DCCOLMSH. HC, 10x12, 296pg, FC $75.00 $65.00 immersive dive into this SIDESHOW FINE ART PRINTS Vol 1 dynamic, fanciful genre. Highly Recommened. By Matthew K. Insightful bios go beyond Manning. Afterword by Tom Gilliland. Wikipedia to give a more Working with top artists such as Alex Ross, accurate and eye-opening Olivia, Paolo Rivera, Adi Granov, Stanley look into the life of each “Artgerm” Lau, and four others, Sideshow artist. Complete with fold- has developed a series of beautifully crafted outs and tipped-in chapter prints based on films, comics, TV, and ani- openers, this collection will mation. These officially licensed illustrations reign as the most exquisite are inspired by countless fan-favorite prop- and informative guide to erties, including everything from Marvel and this popular subject for DC heroes and heroines and Star Wars, to iconic classics like years to come. -

Locus Awards Schedule

LOCUS AWARDS SCHEDULE WEDNESDAY, JUNE 24 3:00 p.m.: Readings with Fonda Lee and Elizabeth Bear. THURSDAY, JUNE 25 3:00 p.m.: Readings with Tobias S. Buckell, Rebecca Roanhorse, and Fran Wilde. FRIDAY, JUNE 26 3:00 p.m.: Readings with Nisi Shawl and Connie Willis. SATURDAY, JUNE 27 12:00 p.m.: “Amal, Cadwell, and Andy in Conversation” panel with Amal El- Mohtar, Cadwell Turnbull, and Andy Duncan. 1:00 p.m.: “Rituals & Rewards” with P. Djèlí Clark, Karen Lord, and Aliette de Bodard. 2:00 p.m.: “Donut Salon” (BYOD) panel with MC Connie Willis, Nancy Kress, and Gary K. Wolfe. 3:00 p.m.: Locus Awards Ceremony with MC Connie Willis and co-presenter Daryl Gregory. PASSWORD-PROTECTED PORTAL TO ACCESS ALL EVENTS: LOCUSMAG.COM/LOCUS-AWARDS-ONLINE-2020/ KEEP AN EYE ON YOUR EMAIL FOR THE PASSWORD AFTER YOU SIGN UP! QUESTIONS? EMAIL [email protected] LOCUS AWARDS TOP-TEN FINALISTS (in order of presentation) ILLUSTRATED AND ART BOOK • The Illustrated World of Tolkien, David Day (Thunder Bay; Pyramid) • Julie Dillon, Daydreamer’s Journey (Julie Dillon) • Ed Emshwiller, Dream Dance: The Art of Ed Emshwiller, Jesse Pires, ed. (Anthology Editions) • Spectrum 26: The Best in Contemporary Fantastic Art, John Fleskes, ed. (Flesk) • Donato Giancola, Middle-earth: Journeys in Myth and Legend (Dark Horse) • Raya Golden, Starport, George R.R. Martin (Bantam) • Fantasy World-Building: A Guide to Developing Mythic Worlds and Legendary Creatures, Mark A. Nelson (Dover) • Tran Nguyen, Ambedo: Tran Nguyen (Flesk) • Yuko Shimizu, The Fairy Tales of Oscar Wilde, Oscar Wilde (Beehive) • Bill Sienkiewicz, The Island of Doctor Moreau, H.G. -

Press Release

NESFA New England Science Fiction Association, Inc. Post Office Box 809 Framingham, MA 01701 United States of America Press Release For Immediate Release Contact: Elisabeth Carey Press Liaison 978-502-2721 [email protected] 47° Boskone Convention Announces Guest of Honor, Official Artist, and Special Guest Boston, MA (October 2009) -- The New England Science Fiction Association, Inc. (NESFA) will hold its 47th Boskone science fiction convention at the Westin Waterfront Hotel in South Boston, MA on February 12-14, 2010. Boskone isa regional science fiction convention focusing on literature, and including many program items on art, science, music, media topics, and gaming. Detailed information is available at www.Boskone.org. The Guest of Honor at Boskone 47 is Alastair Reynolds. A native of Wales, he is one of the key contributors to the new space opera, a part of the field that also includes writers like Iain Banks, Stephen Baxter, and others. He recently second received a one million pound advance from Gollancz for ten books. His novel, Chasm City, won the British Science Fiction Association award in 2002. He was a scientist within the European Space Agency, and spent much of his time working on S-Cam, the world's most advanced optical camera. He is now a full-time writer. In 2005, he was the Hal Clement Science Speaker at Boskone 42, and Boskoue 47 is pleased to welcome him as Cucst of Honor. The Official Artist is John Picacio. He has created covers for works by Harlan Ellison, Michael Moorcock, Robert Silverberg, Neil Gaiman, Hal Clement, and many others. -

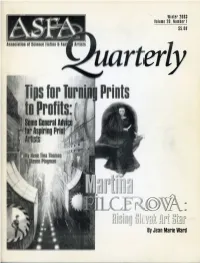

ASFA QUARTERLY WINTER 2003 I 7 Don't Get Me Wrong, We Could ALWAYS of Sorrow

Winter 2003 Volume 20, Number 1 $5.00 Association of Science Fictinn & Fan Artists « • 7 By Jean Marie Ward We Specialize in Original Illustration 8 Artworks in the Fantasy, Science Fiction and Horror Genres <—ECrSi—•—» Catalog #i8 now available - view it and much more online at W0W-ART.com. All print catalogs $15. ppd ($20. overseas) We have more than 500 paintings and sculptures in our inventory spanning 50 years of Imaginative SF/FArt. Worlds of Wopder P.O. Box 814-ASFA, McClean, VA 22101 tel: 703.847.4251 • fax: 703.790.9519 * e-mail: wowartia)erols.com "Worlds of Wonder" is a trademark of Ozma. Inc.d/b/a Books of Wonder and is used under license. ia.i cer. contents winter 2003 volume 20 number 1 ASFA departments ............................................. ASFA.Staff & Directors 5 .................................................Official.Announcements 6 ................................................................. ASFA News ............................................................Letters to ASFA 8.... .....................................................................Obituaries 9... ...................................................President's Message ................................................. Chesley Eligibility List 10 .. .....................Secretary/Publication.Director Report 11 ... 12 .............................................................Treasury Report ...........................................Eastern Director's Report 18 ... 24 .. ....................................................................Art -

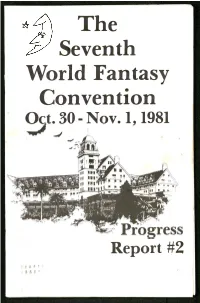

The Convention Itself

The Seventh World Fantasy Convention Oct. 30 - Nov. 1.1981 V ■ /n Jg in iiiWjF. ni III HITV Report #2 I * < ? I fl « f Guests of Honor Alan Garner Brian Frond Peter S. Beagle Master of Ceremonies Karl Edward Wagner Jack Rems, Jeff Frane, Chairmen Will Stone, Art Show Dan Chow, Dealers Room Debbie Notkin, Programming Mark Johnson, Bill Bow and others 1981 World Fantasy Award Nominations Life Achievement: Joseph Payne Brennan Avram Davidson L. Sprague de Camp C. L. Moore Andre Norton Jack Vance Best Novel: Ariosto by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro Firelord by Parke Godwin The Mist by Stephen King (in Dark Forces) The Shadow of the Torturer by Gene Wolfe Shadowland by Peter Straub Best Short Fiction: “Cabin 33” by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro (in Shadows 3) “Children of the Kingdom” by T.E.D. Klein (in Dark Forces) “The Ugly Chickens” by Howard Waldrop (in Universe 10) “Unicorn Tapestry” by Suzy McKee Charnas (in New Dimensions 11) Best Anthology or Collection: Dark Forces ed. by Kirby McCauley Dragons of Light ed. by Orson Scott Card Mummy! A Chrestomathy of Crypt-ology ed. by Bill Pronzini New Terrors 1 ed. by Ramsey Campbell Shadows 3 ed. by Charles L. Grant Shatterday by Harlan Ellison Best Artist: Alicia Austin Thomas Canty Don Maitz Rowena Morrill Michael Whelan Gahan Wilson Special Award (Professional) Terry Carr (anthologist) Lester del Rey (Del Rey/Ballantine Books) Edward L. Ferman (Magazine of Fantasy ir Science Fiction) David G. Hartwell (Pocket/Timescape/Simon & Schuster) Tim Underwood/Chuck Miller (Underwood & Miller) Donald A. Wollheim (DAW Books) Special Award (Non-professional) Pat Cadigan/Arnie Fenner (for Shayol) Charles de Lint/Charles R. -

12 Fantasy: Then, Now and Always 32 Fantasy: Damals, Heute Und Immer 54 La Fantasy Avant, Maintenant Et Toujours Julie Bell

6 MY FANTASY LIFE BY BORIS VALLEJO THE BROTHERS HILDEBRANDT 8 MEIN FANTASYLEBEN VON BORIS VALLEJO 246 MASTERS OF LIGHT 10 MA VIE FANTASY PAR BORIS VALLEJO 254 MEISTER DES LICHTS 260 LES MAÎTRES DE LA LUMIÈRE 12 FANTASY: THEN, NOW AND ALWAYS JEFFREY CATHERINE JONES 32 FANTASY: DAMALS, HEUTE 276 TORTURED GENIUS UND IMMER 282 DAS GEQUÄLTE GENIE 286 LE GÉNIE TORTURÉ 54 LA FANTASY AVANT, MAINTENANT ET TOUJOURS RODNEY MATTHEWS 302 THE ROCK STAR BY ZAK SMITH FANTASY ART ORIGINS 76 308 DER ROCKSTAR VON ZAK SMITH 80 DIE URSPRÜNGE DER FANTASYKUNST 312 LA ROCK-STAR PAR ZAK SMITH 84 LES ORIGINES DU FANTASY ART MŒBIUS 88 FANTASY OR SCI-FI? 330 PSYCHEDELIC SURREALIST 90 FANTASY ODER SCIENCE-FICTION? 336 PSYCHEDELISCHER SURREALIST Page 1: The Giant, print by N. C. Wyeth. 92 FANTASY OU SCIENCE-FICTION? 340 LE SURRÉALISTE PSYCHÉDÉLIQUE Page 2: Hookah, Opium Dream, by Boris Vallejo, for the book Mirage from Ballantine Books, 1982. 94 NEW WORLD, NEW WAVE ROWENA MORRILL Oil on board, 1981, 73.6 x 50.8 cm (29 x 20 inches). 96 NEUE WELT, NEUE WELLE 366 THE PIONEER Tip-on: Nobody did female flesh like Frank NOUVEAU MONDE, NOUVELLE VAGUE 372 DIE PIONIERIN Frazetta, and no booty was better than Princess 98 Duare’s for Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Escape on 376 LA PIONNIÈRE Venus, 1972. This painting, understandably, was used on several reprints of the novel. Oil on JULIE BELL board, 40 x 50.8 cm (15.75 x 20 inches). 102 THE VISIONARY SANJULIAN THE CLASSICIST 108 DIE VISIONÄRIN 388 DER KLASSIZIST 112 LA VISIONNAIRE 394 398 LE CLASSICISTE PHILIPPE DRUILLET BORIS VALLEJO 134 SPACE ARCHITECT BY ZAK SMITH 418 MASTER OF MUSCLE BY ZAK SMITH 142 ARCHITEKT DES RAUMES VON ZAK SMITH 426 MEISTER DER MUSKULATUR VON ZAK SMITH 148 L’ARCHITECTE DE L’ESPACE PAR ZAK SMITH 432 LE MAÎTRE DU MUSCLE PAR ZAK SMITH FRANK FRAZETTA MICHAEL WHELAN 170 THE GOD 456 THE REALIST 178 DER GOTT 462 DER REALIST 184 LE DIEU 466 LE RÉALISTE H. -

Magicon Newsletter

Hhe (DupCicator's Apprentice Late Saturday, September 5, 1992 - Your awards listing Issue #5-A Produced twice daily by Fred Duarte, Editor, riding roughshod over an eclectic concatenation of Gossip Mongers and Rumor Millers for the enlightenment of MagiCon attendees. This zinc is copyright 1992 by MagiCon. All rights reserved. 1992 Hugo Award Winners Best Novel Best Professional Editor Lois McMaster Bujold, Barrayar. Analog'. July - October 1991 (Bacn) Gardner Dozois Best Novella Best Professional Artist Nancy Kress, "Beggars in Spain," Axolod Press, Analog: April 1991 Michael Whelan Best Novelette Best Semiprozine Isaac Asimov, "Gold," Analog: September 1991 Locus, Charles N. Brown (P.O. Box 13305 Oakland, CA 94661) Best Short Story Best Fanzine Geoffrey A. Landis, "A Walk in the Sun," Isaac Asimov's Science Mimosa, Dick & Nicki Lynch (P.O. Box 1350, Germantown, MD Fiction Magazine: October 1991 20875) Best Non-Fiction Book Best Fan Writer Charles Addams, The World of Charles Addams (Knopf) Dave Langford Best Original Artwork Best Fan Artist Michael Whelan, cover of The Summer Queen (Warner Questar) Brad W. Foster Best Dramatic Presentation John W. Campbell Award Terminator 2 (Carolco) Ted Chiang g=£> gj- cr> gs> ga> g 4- £=:> 1991 Chesley Award Winners Presented by the Association of Science Fiction and Fantasy Artists - Best Cover Illustration: Hardback Book Best Monochrome/Unpublished Michael Whelan for The Summer Queen (by Joan D. Vingc) Michael Whelan for Study for All the W’cvrf of Pern Best Cover Illustration: Paperback Book Best -

Downloadable in Late October and in Your Mailbox in Early to Mid-November

Featured New Items FANTASTIC PAINTINGS OF FRAZETTA On our Cover Highly Recommended. By David Spurlock. Afterword by Frank Frazetta Jr. THE BIG TEASE J. David Spurlock started crafting this A Naughty and Nice Collection book by reviving the original million-selling Highly Recommend- 1970s mass market art book, Fantastic Art ed. By Bruce Timm. of Frank Frazetta. Then he expanded and Bruce Timm has revised it to include twice as many images been creating elegant and presents them at a much larger cof- drawings of women fee-table book size of 10.5 x 14.5 inches! for over 30 years, and The collection is brimming with both classic nearly all of these and previously unpublished works of the charming nudes were subjects Frazetta is best remembered for, drawn purely for fun including barbarians, beasts, and buxom after-hours. This beauties. Vanguard, 2020. book collects all three FANPFH. HC, 10x15, 112pg, PC $39.95 Teaser collections from FANTASTIC PAINTINGS OF 2011 to 2013, long sold FRAZETTA Deluxe out. Plus Surrender, Signed by Spurlock and Frank Frazetta, My Sweet from 2015. Jr. 16 bonus pages, variant illustrated In addition, Timm has created new material espe- slipcase. Highly Recommended. cially for this collection and delved into his personal Vanguard, 2020. archives to share pieces not shown before, culmi- FANPFD. HC, 10x15, 128pg, PC $69.95 nating in more than 75 additional pages of material. Abundant nudity. Oversized. Flesk, 2020. Due Oct. SENSUOUS FRAZETTA Deluxe: Mature Readers. 16 Bonus Pages, Variant Cover. BIGT. SC, 9x12, 208pg, PC $39.95 Mature Readers. SENFD. $69.95 Cover Image courtesy of Bruce Timm and Flesk TELLING STORIES The Comic Art of Publications. -

Super Hugos Ballot

Introduction to The Super Hugos Ballot: Dear Worldcon members: As a special tie-in to the 50th Worldcon in Orlando in 1992, Baen Books will publish a book entitled The Super Hugos, which will be compiled by Martin H. Greenberg. This will consist of (at least) the best three stories in the Short Story, Novelette, and Novella categories as determined by vote of the membership of MagiCon. It will also contain memoirs of the stories by the authors, and a complete listing of all winners in all categories. In addition, the book will contain the complete results of the voting for The Super Hugos. Directions: You may vote for up to three stories in each category. These should be rank-ordered as 1, 2, or 3 on your ballot. Please return your ballot before February 1992, to: MagiCon - Best of the Hugos P. O. Box 621992 Orlando, FL 32862-1992 Thanks for your participation in this exciting project. We hope to have a special autographing at the Con for everyone who has ever won a Hugo. BEST SHORT STORY BEST NOVELETTE BEST NOVELLA __ "Bears Discover Fire" by Terry Bisson __ "Adrift, Just Off the Islets of Langerhans" by __ "By Any Other Name" by Spider Robinson __ "The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of Harlan Ellison __ "Cascade Point" by Timothy Zahn the World" by Harlan Ellison __ "The Bicentennial Man" by Isaac Asimov __ "The Dragon Masters" by Jack Vance __ "Boobs" by Suzy McKee Charnas __ "The Big Front Yard" by Clifford D. Simak __ "Enemy Mine" by Barry B.