What Is `` -T,D Deletion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Control of Equilibrium Phases (M,T,S) in the Modified Aluminum Alloy

Materials Transactions, Vol. 44, No. 1 (2003) pp. 181 to 187 #2003 The Japan Institute of Metals EXPRESS REGULAR ARTICLE Control of Equilibrium Phases (M,T,S) in the Modified Aluminum Alloy 7175 for Thick Forging Applications Seong Taek Lim1;*, Il Sang Eun2 and Soo Woo Nam1 1Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, 373-1Guseong-dong, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon, 305-701,Korea 2Agency for Defence Development, P.O. Box 35-5, Yuseong-gu, Daejeon, 305-600, Korea Microstructural evolutions, especially for the coarse equilibrium phases, M-, T- and S-phase, are investigated in the modified aluminum alloy 7175 during the primary processing of large ingot for thick forging applications. These phases are evolved depending on the constitutional effect, primarily the change of Zn:Mg ratio, and cooling rate following solutionizing. The formation of the S-phase (Al2CuMg) is effectively inhibited by higher Zn:Mg ratio rather than higher solutionizing temperature. The formation of M-phase (MgZn2) and T-phase (Al2Mg3Zn3)is closely related with both constitution of alloying elements and cooling rate. Slow cooling after homogenization promotes the coarse precipitation of the M- and T-phases, but becomes less effective as the Zn:Mg ratio increases. In any case, the alloy with higher Zn:Mg ratio is basically free of both T and S-phases. The stability of these phases is discussed in terms of ternary and quaternary phase diagrams. In addition, the modified alloy, Al–6Zn–2Mg–1.3%Cu, has greatly reduced quench sensitivity through homogeneous precipitation, which is uniquely applicable in 7175 thick forgings. -

![214 CHAPTER 5 [T, D]-DELETION in ENGLISH in English, a Coronal Stop](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6032/214-chapter-5-t-d-deletion-in-english-in-english-a-coronal-stop-176032.webp)

214 CHAPTER 5 [T, D]-DELETION in ENGLISH in English, a Coronal Stop

CHAPTER 5 [t, d]-DELETION IN ENGLISH In English, a coronal stop that appears as last member of a word-final consonant cluster is subject to variable deletion – i.e. a word such as west can be pronounced as either [wEst] or [wEs]. Over the past thirty five years, this phenomenon has been studied in more detail than probably any other variable phonological phenomenon. Final [t, d]-deletion has been studied in dialects as diverse as the following: African American English (AAE) in New York City (Labov et al., 1968), in Detroit (Wolfram, 1969), and in Washington (Fasold, 1972), Standard American English in New York and Philadelphia (Guy, 1980), Chicano English in Los Angeles (Santa Ana, 1991), Tejano English in San Antonio (Bayley, 1995), Jamaican English in Kingston (Patrick, 1991) and Trinidadian English (Kang, 1 1994), etc.TP PT Two aspects that stand out from all these studies are (i) that this process is strongly grammatically conditioned, and (ii) that the grammatical factors that condition this process are the same from dialect to dialect. Because of these two facts [t, d]-deletion is particularly suited to a grammatical analysis. In this chapter I provide an analysis for this phenomenon within the rank-ordering model of EVAL. The factors that influence the likelihood of application of [t, d]-deletion can be classified into three broad categories: the following context (is the [t, d] followed by a consonant, vowel or pause), the preceding context (the phonological features of the consonant preceding the [t, d]), the grammatical status of the [t, d] (is it part of the root or 1 TP PT This phenomenon has also been studied in Dutch – see Schouten (1982, 1984) and Hinskens (1992, 1996). -

Tail Risk Premia and Return Predictability∗

Tail Risk Premia and Return Predictability∗ Tim Bollerslev,y Viktor Todorov,z and Lai Xu x First Version: May 9, 2014 This Version: February 18, 2015 Abstract The variance risk premium, defined as the difference between the actual and risk- neutral expectations of the forward aggregate market variation, helps predict future market returns. Relying on new essentially model-free estimation procedure, we show that much of this predictability may be attributed to time variation in the part of the variance risk premium associated with the special compensation demanded by investors for bearing jump tail risk, consistent with idea that market fears play an important role in understanding the return predictability. Keywords: Variance risk premium; time-varying jump tails; market sentiment and fears; return predictability. JEL classification: C13, C14, G10, G12. ∗The research was supported by a grant from the NSF to the NBER, and CREATES funded by the Danish National Research Foundation (Bollerslev). We are grateful to an anonymous referee for her/his very useful comments. We would also like to thank Caio Almeida, Reinhard Ellwanger and seminar participants at NYU Stern, the 2013 SETA Meetings in Seoul, South Korea, the 2013 Workshop on Financial Econometrics in Natal, Brazil, and the 2014 SCOR/IDEI conference on Extreme Events and Uncertainty in Insurance and Finance in Paris, France for their helpful comments and suggestions. yDepartment of Economics, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, and NBER and CREATES; e-mail: [email protected]. zDepartment of Finance, Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208; e-mail: [email protected]. xDepartment of Finance, Whitman School of Management, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 13244- 2450; e-mail: [email protected]. -

Tail of a Linear Diffusion with Markov Switching

The Annals of Applied Probability 2005, Vol. 15, No. 1B, 992–1018 DOI: 10.1214/105051604000000828 c Institute of Mathematical Statistics, 2005 TAIL OF A LINEAR DIFFUSION WITH MARKOV SWITCHING By Benoˆıte de Saporta and Jian-Feng Yao Universit´ede Rennes 1 Let Y be an Ornstein–Uhlenbeck diffusion governed by a sta- tionary and ergodic Markov jump process X: dYt = a(Xt)Yt dt + σ(Xt) dWt, Y0 = y0. Ergodicity conditions for Y have been obtained. Here we investigate the tail propriety of the stationary distribution of this model. A characterization of either heavy or light tail case is established. The method is based on a renewal theorem for systems of equations with distributions on R. 1. Introduction. The discrete-time models Y = (Yn,n ∈ N) governed by a switching process X = (Xn,n ∈ N) fit well to the situations where an autonomous process X is responsible for the dynamic (or regime) of Y . These models are parsimonious with regard to the number of parameters, and extend significantly the case of a single regime. Among them, the so- called Markov-switching ARMA models are popular in several application fields, for example, in econometric modeling [see Hamilton (1989, 1990)]. More recently, continuous-time versions of Markov-switching models have been proposed in Basak, Bisi and Ghosh (1996) and Guyon, Iovleff and Yao (2004), where ergodicity conditions are established. In this paper we investi- gate the tail property of the stationary distribution of this continuous-time process. One of the main results (Theorem 2) states that this model can provide heavy tails, which is one of the major features required in nonlinear time-series modeling. -

U.S. EPA, Pesticide Product Label, NEEMAZAL T/S 1.2%EC

Page 1 NEEMAZAL TM T/S-1.2% EC Draft Label February 17, 2000 NEEMAZAL ™ - TIS 1.2% EC INSECTICIDE NEEM·BASED BIOLOGICAL INSECTICIDE, REPELLANT, ANTIFEEDANT AND INSECT GROWTH REGULATOR BOTANICAL PRODUCT FOR CONTROL OF INSECTS ON INDOOR AND OUTDOOR VEGETABLES AND CROPS, ORNAMENTAL FLOWERS, TREES, SHRUBS AND PLANTS ACTIVE INGREDIENT: Azadirachtin .......... 1.2% OTHER INGREDIENTS: .................. 98.8% 100.0% Contains 0.0987 Ib azadirachtin per gallon. (Contains 0.0123 Ib azadirachtin per pint.) KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN CAUTION FIRST AID IF ON SKIN: Wash with plenty of soap and water. Get medical attention. IF INHALED: Move person to fresh air. If not breathing, give artificial respiration, preferably mouth-to-mouth. Get medical attention. IF IN EYES: Flush eyes with plenty of water. Call a physician if irritation persists. READ ALL DIRECTIONS BEFORE USING THIS PRODUCT E.I.D. Parry, LTD. CCEPTE Net Contents, ____ Dare House APR 26 2000 Post Box No. 12 EPA Reg. No. 71908- Madras 6000 001 v... •• r....s .. c.... EPA Est. No., ___ '1 •• INDIA '.11__ ........11__1' 5!''', prtt .. ...1 t I' ,_I?~A.!d<..!lt:..J.ju.l::"':::"-'"..4 ........ Page 2 NEEMAZAL ™ T/S-1.2% EC Draft Label February 17, 2000 NEEMAZAL ™ - TIS 1.2% EC INSECTICIDE BOTANICAL PRODUCT FOR CONTROL OF INSECTS ON INDOOR AND OUTDOOR VEGETABLES, ORNAMENTAL FLOWERS, TREES, SHRUBS AND PLANTS. SEE ATTACHMENT FOR DIRECTIONS FOR USE. PRODUCT MODE OF ACTION: NeemAzal T/S 1.2% EC controls target pests on contact or by ingestion. The product acts on pests by way of repellence, antifeedance, and interference with the molting process. -

Proposal for Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone

Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone Proposal for Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone Table of Contents 1. General Information 2 1.1 Use of Latin Script characters in domain names 3 1.2 Target Script for the Proposed Generation Panel 4 1.2.1 Diacritics 5 1.3 Countries with significant user communities using Latin script 6 2. Proposed Initial Composition of the Panel and Relationship with Past Work or Working Groups 7 3. Work Plan 13 3.1 Suggested Timeline with Significant Milestones 13 3.2 Sources for funding travel and logistics 16 3.3 Need for ICANN provided advisors 17 4. References 17 1 Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone 1. General Information The Latin script1 or Roman script is a major writing system of the world today, and the most widely used in terms of number of languages and number of speakers, with circa 70% of the world’s readers and writers making use of this script2 (Wikipedia). Historically, it is derived from the Greek alphabet, as is the Cyrillic script. The Greek alphabet is in turn derived from the Phoenician alphabet which dates to the mid-11th century BC and is itself based on older scripts. This explains why Latin, Cyrillic and Greek share some letters, which may become relevant to the ruleset in the form of cross-script variants. The Latin alphabet itself originated in Italy in the 7th Century BC. The original alphabet contained 21 upper case only letters: A, B, C, D, E, F, Z, H, I, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, V and X. -

When a Stroke Happens

When a stroke happens When a stroke happens What to expect during the first hours, days and weeks after a stroke We’re for life after stroke Introduction Need to talk? Every year, there are about 152,000 strokes "I was at home with Call our confidential Stroke Helpline on in the UK. That’s more than one every five my wife when I 0303 3033 100. minutes. Most people affected are over started to feel very 65, but anyone can have a stroke, including ill and couldn’t move You may also find our other leaflets helpful. children and babies. my arm. She realised I was having a stroke • We are the Stroke Association A stroke is sudden and can be life-changing as the FAST test • What is a stroke? for you and your family. It usually involves helped her identify • How to prevent a stroke staying in hospital, having tests and being on it. She called 999 • Life after stroke medication to help prevent further strokes. and I was rushed to • The road to recovery This leaflet explains what you can expect hospital." to happen when you have had a stroke, We also have lots more useful information. from emergency care to beginning your Darren, stroke survivor To order leaflets and factsheets, or to find out rehabilitation and recovery. more about stroke, please call 0303 3033 100, email [email protected] or visit us at stroke.org.uk. Contents We are a charity. We rely on your support • What is a stroke? – page 4 to change lives. -

Formation May Result in the Denial Or Revocation of Registration

TEMPLATE: DO NOT SEND TO NFA NATIONAL FUTURES ASSOCIATION INDIVIDUAL WITHDRAWAL Instructions for Using the Individual Withdrawal Template READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS CAREFULLY BEFORE COMPLETING OR REVIEWING THE APPLICATION. THE FAILURE TO ANSWER ALL QUESTIONS COMPLETELY AND ACCURATELY OR THE OMISSION OF REQUIRED INFORMATION MAY RESULT IN THE DENIAL OR REVOCATION OF REGISTRATION. THE FAILURE TO DISCLOSE A DISCIPLINARY MATTER EITHER IN AN APPLICATION OR AN UPDATE WILL RESULT IN THE IMPOSITION OF A LATE DISCLOSURE FEE IN ACCORDANCE WITH NFA REGISTRATION RULE 210(c). This document is not an Individual Withdrawal Notice form. Do not send this document to NFA. It is a template that you may use to assist in filing the electronic notice. You may fill out the template online and save and/or print it when you are finished or you can download the template and/or print it and fill it out later. Not every section applies to every individual. Certain sections apply depending on the whether some or all of the individual’s registration categories with the individual’s sponsor are being withdrawn. The text above these sections explains who must complete the section. In the electronic notice, only the applicable sections will appear. Withdrawal Reason and Disciplinary Information Sections These sections concern matters that are required to be disclosed if all of the individual’s registration categories with the sponsor are being withdrawn. The Disciplinary Information section does not need to be completed if the individual’s registration categories are being terminated because the individual is deceased. Only Sponsors that are SEC registered Broker-Dealers may elect to complete the Disciplinary Information-Form U5 section. -

Speech Entitled “Ain't I a Woman?” by Sojourner Truth

Speech Entitled “Ain’t I a Woman?” by Sojourner Truth Delivered at the 1851 Women’s Convention in Akron, Ohio Well, children, where there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that ‘twixt the Negroes of the South and the women at the North, all talking about rights, the white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what’s all this here talking about? That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man – when I could get it – and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman? Then they talk about this thing in the head; what’s this they call it? [member of audience whispers, “intellect”] That’s it, honey. What’s that got to do with women’s rights or Negroes’ rights? If my cup won’t hold but a pint, and yours holds a quart, wouldn’t you be mean not to let me have my little half measure full? Then that little man in black there, he says women can’t have as much rights as men, ‘cause Christ wasn’t a woman! Where did your Christ Sojourner Truth “Ain’t I Woman?”, Speech Delivered at Ohio Women’s Rights Convention, May 1851 come from? Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him. -

Get with the Guidelines®-Stroke Is the American Heart Association's

Get With The Guidelines®-Stroke is the American Heart Association’s collaborative performance improvement program, demonstrated to improve adherence to evidence-based care of patients hospitalized with stroke. The program provides hospitals with a Web-based Patient Management Tool™ (powered by QuintilesIMS), decision support, a robust registry, real-time benchmarking capabilities and other performance improvement methodologies toward the goal of enhancing patient outcomes and saving lives. This fact sheet provides an overview of the achievement, quality, descriptive, and reporting measures currently reported on via Get With The Guidelines-Stroke. Get With The Guidelines-Stroke is for patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA). The following is a list of the common stroke-related diagnoses included in Get With The Guidelines-Stroke: ICD-10: I60*; I61*; I63*; G45.0, G45.1, G45.8, G45.9 STROKE ACHIEVEMENT MEASURES ACUTE: • IV rt-PA arrive by 2 hour, treat by 3 hour: Percent of acute ischemic stroke patients who arrive at the hospital within 120 minutes (2 hours) of time last known well and for whom IV t-PA was initiated at this hospital within 180 minutes (3 hours) of time last known well. Corresponding measure available for inpatient stroke cases • Early antithrombotics: Percent of patients with ischemic stroke or TIA who receive antithrombotic therapy by the end of hospital day two. Corresponding measures available for observation status only & inpatient stroke cases • VTE prophylaxis: Percent of patients with ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, or stroke not otherwise specified who receive VTE prophylaxis the day of or the day after hospital admission. AT OR BY DISCHARGE: • Antithrombotics: Percent of patients with an ischemic stroke or TIA prescribed antithrombotic therapy at discharge. -

Fonts for Latin Paleography

FONTS FOR LATIN PALEOGRAPHY Capitalis elegans, capitalis rustica, uncialis, semiuncialis, antiqua cursiva romana, merovingia, insularis majuscula, insularis minuscula, visigothica, beneventana, carolina minuscula, gothica rotunda, gothica textura prescissa, gothica textura quadrata, gothica cursiva, gothica bastarda, humanistica. User's manual 5th edition 2 January 2017 Juan-José Marcos [email protected] Professor of Classics. Plasencia. (Cáceres). Spain. Designer of fonts for ancient scripts and linguistics ALPHABETUM Unicode font http://guindo.pntic.mec.es/jmag0042/alphabet.html PALEOGRAPHIC fonts http://guindo.pntic.mec.es/jmag0042/palefont.html TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER Page Table of contents 2 Introduction 3 Epigraphy and Paleography 3 The Roman majuscule book-hand 4 Square Capitals ( capitalis elegans ) 5 Rustic Capitals ( capitalis rustica ) 8 Uncial script ( uncialis ) 10 Old Roman cursive ( antiqua cursiva romana ) 13 New Roman cursive ( nova cursiva romana ) 16 Half-uncial or Semi-uncial (semiuncialis ) 19 Post-Roman scripts or national hands 22 Germanic script ( scriptura germanica ) 23 Merovingian minuscule ( merovingia , luxoviensis minuscula ) 24 Visigothic minuscule ( visigothica ) 27 Lombardic and Beneventan scripts ( beneventana ) 30 Insular scripts 33 Insular Half-uncial or Insular majuscule ( insularis majuscula ) 33 Insular minuscule or pointed hand ( insularis minuscula ) 38 Caroline minuscule ( carolingia minuscula ) 45 Gothic script ( gothica prescissa , quadrata , rotunda , cursiva , bastarda ) 51 Humanist writing ( humanistica antiqua ) 77 Epilogue 80 Bibliography and resources in the internet 81 Price of the paleographic set of fonts 82 Paleographic fonts for Latin script 2 Juan-José Marcos: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The following pages will give you short descriptions and visual examples of Latin lettering which can be imitated through my package of "Paleographic fonts", closely based on historical models, and specifically designed to reproduce digitally the main Latin handwritings used from the 3 rd to the 15 th century. -

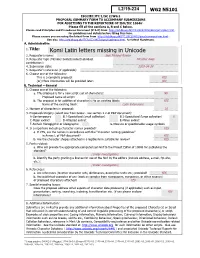

Komi Latin Letters Missing in Unicode 2

WG2 N5101 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS 1 FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 10646TP PT Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from HTU http://std.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html UTH for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from HTU http://std.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.htmlUTH. See also HTU http://std.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html UTH for latest Roadmaps. A. AdministratiVe 1. Title: Komi Latin letters missing in Unicode 2. Requester's name: Jack Michael Rueter 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual Member body contribution): 4. Submission date: 2019-04-24 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: YES (or) More information will be provided later: NO B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): NO Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: YES Name of the existing block: Latin Extensions 2. Number of characters in proposal: 16 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary B.1-Specialized (small collection) B.2-Specialized (large collection) X C-Major extinct D-Attested extinct E-Minor extinct F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols 4.