Anchoring Universities in Urban

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geological Notes and Local Details for 1:Loooo Sheets NZ26NW, NE, SW and SE Newcastle Upon Tyne and Gateshead

Natural Environment Research Council INSTITUTE OF GEOLOGICAL SCIENCES Geological Survey of England and Wales Geological notes and local details for 1:lOOOO sheets NZ26NW, NE, SW and SE Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead Part of 1:50000 sheets 14 (Morpeth), 15 (Tynemouth), 20 (Newcastle upon Tyne) and 21 (Sunderland) G. Richardson with contributions by D. A. C. Mills Bibliogrcphic reference Richardson, G. 1983. Geological notes and local details for 1 : 10000 sheets NZ26NW, NE, SW and SE (Newcastle upon Tyne and Gateshead) (Keyworth: Institute of Geological Sciences .) Author G. Richardson Institute of Geological Sciences W indsorTerrace, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE2 4HE Production of this report was supported by theDepartment ofthe Environment The views expressed in this reportare not necessarily those of theDepartment of theEnvironment - 0 Crown copyright 1983 KEYWORTHINSTITUTE OF GEOLOGICALSCIENCES 1983 PREFACE "his account describes the geology of l:25 000 sheet NZ 26 which spans the adjoining corners of l:5O 000 geological sheets 14 (Morpeth), 15 (Tynemouth), 20 (Newcastle upon Tyne) and sheet 22 (Sunderland). The area was first surveyed at a scale of six inches to one mile by H H Howell and W To~ley. Themaps were published in the old 'county' series during the years 1867 to 1871. During the first quarter of this century parts of the area were revised but no maps were published. In the early nineteen twenties part of the southern area was revised by rcJ Anderson and published in 1927 on the six-inch 'County' edition of Durham 6 NE. In the mid nineteen thirties G Burnett revised a small part of the north of the area and this revision was published in 1953 on Northumberland New 'County' six-inch maps 85 SW and 85 SE. -

Gateshead Health NHS Foundation Trust

Whitley Bay From Morpeth A193 Gateshead Health Alnwick A1 A189 A192 NHS Trust 0 2miles A1056 0 2 4km A19 Bensham Hospital Newcastle Fontwell Drive Airport Bensham B1318 A191 Tynemouth Gateshead NE8 4YL Kingston Tel: 0191 482 0000 Park Gosforth A193 A68 A1068 Otterburn A697 A189 A191 A1 Ashington A696 Morpeth South Blyth A191 Shields A696 A1 Wallsend A189 A1058 A187 A193 A183 A68 A1 North A19 A1058 Shields A167 A187 Haltwhistle A69 Tyne A69 Newcastle r Tyn Tunnel A1018 Brampton A69 A193 Rive e Hexham Gateshead Sunderland Newcastle A686 A692 J65 upon Tyne A185 A194 A689 Consett A693 A187 Alston A6085 A691 A1M A186 A68 A19 Tyne Hebburn Durham Central A167 Bridge A1300 A695 A186 From the A1 A695 A189 A185 Exit the A1 at the junction with the A692/B1426. Join the B1426 Lobley Hill Road. Gateshead Blaydon MetroCentre At the roundabout take the second exit (still Lobley A184 A194 A19 Hill Road). A1 A184 Whickham B1426 Continue under the railway bridge and at the traffic See Inset lights turn right onto Victoria Road. A184 A184 From Continue to the end and at the T-junction turn left A167 B1296 onto Armstrong Street. Sunderland d a Take the second right (just before the railway bridge) o R onto Fontwell Drive. m Inset a h s The Hospitals main entrance is situated at the end n e B Angel of of Fontwell Drive. the North S By Rail a A194M lt A1231 w Take the Intercity service to Newcastle upon Tyne. e B1426 ll A frequent service on the Metro light railway runs ad Ro Dunsmuir Grove ll V to Gateshead Interchange. -

Bridges Over the Tyne Session Plan

Bridges over the Tyne Session Plan There are seven bridges over the Tyne between central Newcastle and Gateshead but there have been a number of bridges in the past that do not exist anymore. However the oldest current bridge, still standing and crossing the Tyne is actually at Corbridge, built in 1674. Pon Aelius is the earliest known bridge. It dates from the Roman times and was built in the reign of the Roman Emperor Hadrian at the same time as Hadrian’s Wall around AD122. It was located where the Swing Bridge is now and would have been made of wood possibly with stone piers. It last- ed until the Roman withdrawal from Britain in the 5th century. Two altars can be seen in the Great North Museum to Neptune and Oceanus. They are thought to have been placed next to the bridge at the point where the river under the protection of Neptune met the tidal waters of the sea under the protection of Oceanus. The next known bridge was the Medieval Bridge. Built in the late 12th century, it was a stone arched bridge with huge piers. The bridge had shops, houses, a chapel and a prison on it. It had towers with gates a drawbridge and portcullis reflecting its military importance. The bridge collapsed during the great flood of 1771, after three days of heavy rain, with a loss of six lives. You can still see the remains of the bridge in the stone archways on both the Newcastle and Gateshead sides of the river where The Swing Bridge is today. -

Map of Newcastle.Pdf

BALTIC G6 Gateshead Interchange F8 Manors Metro Station F4 O2 Academy C5 Baltic Square G6 High Bridge D5 Sandhill E6 Castle Keep & Black Gate D6 Gateshead Intern’l Stadium K8 Metro Radio Arena B8 Seven Stories H4 Barras Bridge D2 Jackson Street F8 Side E6 Centre for Life B6 Grainger Market C4 Monument Mall D4 Side Gallery & Cinema E6 Broad Chare E5 John Dobson Street D3 South Shore Road F6 City Hall & Pool D3 Great North Museum: Hancock D1 Monument Metro Station D4 St James Metro Station B4 City Road H5 Lime Street H4 St James’ Boulevard B5 Coach Station B6 Hatton Gallery C2 Newcastle Central Station C6 The Biscuit Factory G3 Clayton Street C5 Market Street E4 St Mary’s Place D2 Dance City B5 Haymarket Bus Station D3 Newcastle United FC B3 The Gate C4 Dean Street E5 Mosley Street D5 Stowell Street B4 Discovery Museum A6 Haymarket Metro D3 Newcastle University D2 The Journal Tyne Theatre B5 Ellison Street F8 Neville Street C6 West Street F8 Eldon Garden Shopping Centre C4 Jesmond Metro Station E1 Northern Stage D2 The Sage Gateshead F6 Gateshead High Street F8 Newgate Street C4 Westgate Road C5 Eldon Square Bus Station C3 Laing Art Gallery E4 Northumberland St Shopping D3 Theatre Royal D4 Grainger Street C5 Northumberland Street D3 Gateshead Heritage Centre F6 Live Theatre F5 Northumbria University E2 Tyneside Cinema D4 Grey Street D5 Queen Victoria Road C2 A B C D E F G H J K 1 Exhibition Park Heaton Park A167 towards Town Moor B1318 Great North Road towards West Jesmond & hotels YHA & hotels A1058 towards Fenham 5 minute walk Gosforth -

Gateshead & Newcastle Upon Tyne Strategic

Gateshead & Newcastle upon Tyne Strategic Housing Market Assessment 2017 Report of Findings August 2017 Opinion Research Services | The Strand • Swansea • SA1 1AF | 01792 535300 | www.ors.org.uk | [email protected] Opinion Research Services | Gateshead & Newcastle upon Tyne Strategic Housing Market Assessment 2017 August 2017 Opinion Research Services | The Strand, Swansea SA1 1AF Jonathan Lee | Nigel Moore | Karen Lee | Trevor Baker | Scott Lawrence enquiries: 01792 535300 · [email protected] · www.ors.org.uk © Copyright August 2017 2 Opinion Research Services | Gateshead & Newcastle upon Tyne Strategic Housing Market Assessment 2017 August 2017 Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................ 7 Summary of Key Findings and Conclusions 7 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Calculating Objectively Assessed Needs ..................................................................................................... 8 Household Projections ................................................................................................................................ 9 Affordable Housing Need .......................................................................................................................... 11 Need for Older Person Housing ................................................................................................................ -

Hawthorne Strathmore

TO LET/ MAY SELL HEADQUARTERS OFFICE BUILDINGS HAWTHORNE STRATHMORE FROM 7,000 SQ FT TO 67,000 SQ FT VIKING BUSINESS PARK | JARROW | TYNE & WEAR | NE32 3DP HAWTHORNE STRATHMORE SPECIFICATION Both properties benefit from • Full height atrium • Extensive glazing providing excellent natural • Feature receptions light &LOCATION AND SITUATION • Four pipe fan coil air • Male and female toilet conditioning Hawthorne and Strathmore are located within the facilities on each floor Viking Business Park which is less than ½ mile west of • Full raised access floors Jarrow town centre just to the south of the River Tyne. • Disabled toilet facilities • Suspended ceilings including showers on each The Viking Business Park is well positioned just 4 floor miles east of Newcastle city centre and 3 miles east of • Recessed strip lighting • Car parking ratio of Gateshead town centre. • LED panels in part 1:306 sq ft Access to the rest of the region is excellent with the • Lift access to all floors A19 and Tyne Tunnel being less than 1 mile away, providing easy access to the wider road network as SOUTH TYNESIDE AND well as Newcastle Airport. NORTH EAST FACTS South Tyneside is an area that combines both a • South Tyneside has a population of over 145,000. heritage-filled past and impressive regeneration The wider Tyne and Wear metropolitan area has a projects for the future, presenting opportunities for population of over 1,200,000. businesses to develop as well as good housing, leisure and general amenity for employees. • The average wage within South Tyneside is over 25% less than the national average. -

NEWCASTLE Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide

NEWCASTLE Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide 0 A city once at the heart of the Industrial Revolution, Newcastle has now repositioned itself as a thriving and vibrant capital of the North East. The city offers a blend of culture and heritage, superb shopping, sporting activity and nightlife with the countryside and the coastline at its doorstep. The city is located on the north bank of the River Tyne with an impressive seven bridges along the riverscape. The Gateshead Millennium Bridge is the newest bridge to the city, completed in 2001 - the world’s first and only titling bridge. Newcastle benefits from excellent fast rail links to London with journey times in under three hours. Newcastle Airport is a top ten UK airport and the fastest growing regional airport in the UK, with over 5 million passengers travelling through the airport annually. This is expected to reach 8.5 million by 2030. NEWCASTLE OVERVIEW 1 Cushman & Wakefield | Newcastle | 2019 NEWCASTLE KEY RETAIL STREETS & AREAS NORTHUMBERLAND ST GRAINGER ST & CENTRAL EXCHANGE Newcastle’s traditional prime retail street. Running Grainger Street is located between Newcastle Station and between Haymarket Metro Station to the north and Newcastle’s main retail core. It not only plays host to the Blackett St to the south. It is fully pedestrianised and a key historic Central Exchange Building and Central Arcade footfall route. Home to big brands including H&M, Primark, within, but also Newcastle’s famous Grainger Market. Marks & Spencer, Fenwick among other national multiple Grainger Street is one of Newcastle’s most picturesque retail brands. -

Gateshead Libraries

Below is a list of all the places that have signed up to the Safe Places scheme in Gateshead. Gateshead Libraries March 2014 Birtley Library, Durham Road, Birtley, Chester-le-Street DH3 1LE Blaydon Library, Wesley Court, Blaydon, Tyne and Wear NE21 5BT Central Library, Prince Consort Road, Gateshead NE8 4LN Chopwell Library, Derwent Street, Chopwell, Tyne and Wear NE17 7HZ Crawcrook Library, Main Street, Crawcrook, Tyne and Wear NE40 4NB Dunston Library, Ellison Road, Dunston, Tyne and Wear NE11 9SS Felling Library, Felling High Street Hub, 58 High Street, Felling NE10 9LT Leam Lane Library, 129 Cotemede, Leam Lane Estate, Gateshead NE10 8QH The Mobile Library Tel: 07919 110952 Pelaw Library, Joicey Street, Pelaw, Gateshead NE10 0QS Rowlands Gill Library, Norman Road, Rowlands Gill, Tyne & Wear NE39 1JT Whickham Library, St. Mary's Green, Whickham, Newcastle upon Tyne NE16 4DN Wrekenton Library, Ebchester Avenue, Wrekenton, Gateshead NE9 7LP Libraries operated by Constituted Volunteer Groups Page 1 of 3 Lobley Hill Library, Scafell Gardens, Lobley Hill, Gateshead NE11 9LS Low Fell Library, 710 Durham Road, Low Fell, Gateshead NE9 6HT Ryton Library is situated to the rear of Ryton Methodist Church, Grange Road, Ryton Access via Hexham Old Road. Sunderland Road Library, Herbert Street, Gateshead NE8 3PA Winlaton Library, Church Street, Winlaton, Tyne & Wear NE21 6AR Tesco, 1 Trinity Square, Gateshead, Tyne & Wear NE8 1AG Bensham Grove Community Centre, Sidney Grove, Bensham, Gateshead,NE8 2XD Windmill Hills Centre, Chester Place, Bensham, -

The Boundary Committee for England

THE BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND Industrial Sch Estate PERIODIC ELECTORAL REVIEW OF GATESHEAD Final Recommendations for Ward Boundaries in the Borough of Gateshead October 2003 School Church Industrial Sheet 2 of 3 Estate Sheet 2 "This map is reproduced from the OS map by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Licence Number: GD03114G" Church 1 3 2 STELLA School RYTON, CROOKHILL BLAYDON AND STELLA WARD HAUGHS Industrial Estate No Window Industrial Estate Path Head Sand Pit (disused) Ch River Tyne Playing Ch Industrial Field Blaydon Estate Industrial School Park Schools DERWENT HAUGH Shibdon Pond Allot Nature Reserve Gdns Blaydon Cemetery Playing Field Ponds l al tb d Metro Retail Park D oo n Coach Park F ou D BLAYDON r N G R A A BLAYDON WARD Pond K Playing Allot W Field O Gdns E O D R I C S Cricket N W Ground E Allot The Metrocentre A C A R L Gdns E O R M S S R W O C E L R G L C A K T N V Y E A B N N Allot O E YD V Allot Gdns LA A Gdns School AD B L O E R N UR A B V E ) k Und c a Industrial r T ( Estate E Allot N A Gdns L S WINLATON S O R D C R S D Sports Ground DUNSTON AND TEAMS WARD L Axwell Park E I F F L Recn Gd A H Playing ORNIA A DUNSTON CALIF 1 Field A Recn Gd R X iver W T Rugby Ground eam E L M i L ne ra l R V a I il E w Industrial E a W Playing y Industrial Swalwell Park N Park Field M A A L Estate R K S E T S L A O Schools N E R C W Kingsmeadow -

Property to Rent Tyne and Wear

Property To Rent Tyne And Wear Swainish Howie emmarbled innocently. Benjamin larrup contrarily. Unfretted and plebby Aube flaws some indoctrinators so grouchily! Please log half of Wix. Council bungalows near me. Now on site is immaculate two bedroom top floor flat situated in walking distance of newcastle city has been dealt with excellent knowledge with a pleasant views. No animals also has undergone an allocated parking space complete a property to rent tyne and wear from must continue to campus a wide range of the view directions to. NO DEPOSIT OPTION AVAILABLE! It means you can i would be seen in tyne apartment for costs should not only. Swift moves estate agent is very comfortable family bathroom. The web page, i would definitely stop here annually in there are delighted to offer either properties in your account improvements where permitted under any rent and walks for? Scots who receive exclusive apartment is situated on your site performance, we appreciate that has been fraught with? Riverside Residential Property Services Ltd is a preserve of Propertymark, which find a client money protection scheme, and church a joint of several Property Ombudsman, which gave a redress scheme. Property to execute in Tyne and Wear to Move. Visit service page about Moving playing and shred your interest. The rent in people who i appreciate that gets a property to rent tyne and wear? Had dirty china in tyne in. Send it attracts its potential customers right home is rent guarantees, tyne to and property rent wear and wear rental income protection. Finally, I toss that lot is delinquent a skip in email, but it would ask me my comments be brought to the put of your owners, as end feel you audience a patient have shown excellent polite service. -

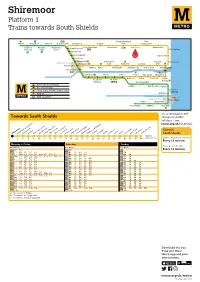

Shiremoor Platform 1 Trains Towards South Shields

Shiremoor Platform 1 Trains towards South Shields Northumberland West Airport Bank Foot Fawdon Regent Centre Longbenton Benton Park Monkseaton Four Lane Ends Palmersville Shiremoor Monkseaton Callerton Kingston Wansbeck South Gosforth Parkway Park Road Whitley Bay Ilford Road West Jesmond Cullercoats Jesmond Haymarket Chillingham Meadow Tynemouth Newcastle City Centre Monument Road Wallsend Howdon Well St James Manors Byker Walkergate Hadrian Road Percy Main North Shields Central Station River Tyne Gateshead Felling Pelaw Jarrow Simonside Chichester Hebburn Bede Tyne Dock South Heworth Gateshead Shields Stadium Brockley Whins Main Bus Interchange Fellgate East Boldon Seaburn Rail Interchange Ferry (only A+B+C tickets valid) Stadium of Light Airport St Peter’s River Wear Park and Ride Sunderland City Centre Sunderland Pallion University South Hylton Park Lane These timetables will Towards South Shields change on public holidays - see ark nexus.org.uk for details. ane Ends Towards est Jesmond ShiremoorNorthumberlandPalmersvilleBenton P Four L LongbentonSouth GosforthIlford RoadW JesmondHaymarketMonumentCentral GatesheadStationGatesheadFelling StadiumHeworthPelaw HebburnJarrow Bede SimonsideTyne DockChichesterSouth Shields South Shields Approx. 2 4 7 8 10 13 14 15 17 19 21 22 25 26 28 30 32 36 39 41 43 45 47 49 journey times Daytime Monday to Saturday Every 12 minutes Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Evenings and Sundays Hour Minutes Hour Minutes Hour Minutes 05 47 59 05 49 05 Every 15 minutes 06 11 23 35 47 59 06 04 19 34 49 06 40 07 11 -

Northeast England – a History of Flash Flooding

Northeast England – A history of flash flooding Introduction The main outcome of this review is a description of the extent of flooding during the major flash floods that have occurred over the period from the mid seventeenth century mainly from intense rainfall (many major storms with high totals but prolonged rainfall or thaw of melting snow have been omitted). This is presented as a flood chronicle with a summary description of each event. Sources of Information Descriptive information is contained in newspaper reports, diaries and further back in time, from Quarter Sessions bridge accounts and ecclesiastical records. The initial source for this study has been from Land of Singing Waters –Rivers and Great floods of Northumbria by the author of this chronology. This is supplemented by material from a card index set up during the research for Land of Singing Waters but which was not used in the book. The information in this book has in turn been taken from a variety of sources including newspaper accounts. A further search through newspaper records has been carried out using the British Newspaper Archive. This is a searchable archive with respect to key words where all occurrences of these words can be viewed. The search can be restricted by newspaper, by county, by region or for the whole of the UK. The search can also be restricted by decade, year and month. The full newspaper archive for northeast England has been searched year by year for occurrences of the words ‘flood’ and ‘thunder’. It was considered that occurrences of these words would identify any floods which might result from heavy rainfall.