Mistletoe by Jim Gormely

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABSTRACT Savannah Dehart. BRACTEATES AS INDICATORS OF

ABSTRACT Savannah DeHart. BRACTEATES AS INDICATORS OF NORTHERN PAGAN RELIGIOSITY IN THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES. (Under the direction of Michael J. Enright) Department of History, May 2012. This thesis investigates the religiosity of some Germanic peoples of the Migration period (approximately AD 300-800) and seeks to overcome some difficulties in the related source material. The written sources which describe pagan elements of this period - such as Tacitus’ Germania, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, and Paul the Deacon’s History of the Lombards - are problematic because they were composed by Roman or Christian authors whose primary goals were not to preserve the traditions of pagans. Literary sources of the High Middle Ages (approximately AD 1000-1400) - such as The Poetic Edda, Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda , and Icelandic Family Sagas - can only offer a clearer picture of Old Norse religiosity alone. The problem is that the beliefs described by these late sources cannot accurately reflect religious conditions of the Early Middle Ages. Too much time has elapsed and too many changes have occurred. If literary sources are unavailing, however, archaeology can offer a way out of the dilemma. Rightly interpreted, archaeological evidence can be used in conjunction with literary sources to demonstrate considerable continuity in precisely this area of religiosity. Some of the most relevant material objects (often overlooked by scholars) are bracteates. These coin-like amulets are stamped with designs that appear to reflect motifs from Old Norse myths, yet their find contexts, including the inhumation graves of women and hoards, demonstrate that they were used during the Migration period of half a millennium earlier. -

Pucker Up! It's That Time of Year. Once Again the Airwaves Are Filled with Beautiful Christmas Songs. Most Convey a Message

Yard and Garden – 12-19-2015 – Ted Griess/Extension Horticulture Assistant Pucker up! It’s that time of year. Once again the airwaves are filled with beautiful Christmas songs. Most convey a message of joy and peace on earth to all humankind. However, some Christmas tunes include in their lyrics the name of a certain plant that conveys a reason to start kissing. For example, take the song I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus, or how about The Christmas Song better known as Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire? Then, there is the song I’ll Be Home for Christmas. These are just a few Christmas tunes that have in their lyrics the name of a plant scientifically known as Viscum album. Most of us know it as mistletoe. Throughout history, mistletoe has inspired all sorts of mystique and charm. It is perceived to hold magical properties. When mistletoe is in our presence, it supposedly creates an amorous atmosphere for us humans to start kissing. In contrast, this plant is actually parasitic. A parasite is defined as an organism that lives in or on another organism (its host) and benefits by deriving nutrients at the host’s expense. Mistletoe has leathery evergreen leaves with waxy white berries. It grows primarily on the branches of deciduous trees such as ash, hawthorn and oak. Deemed somewhat tropical, it is found growing mostly in areas of California and Florida. When a seed from the berry of mistletoe comes in contact with the bark of a host tree, it germinates, sending out fine thread-like roots penetrating the bark anchoring firmly into the living tissue of the host, and absorbing its nutrients. -

Youth Ballet's the Nutcracker: COVID-19 Style

THE GLEANER HOLIDAY FEATURES 4 DECEMBER 18, 2020 Youth Ballet’s The Nutcracker: COVID-19 style by Ava Hoelscher The dancers have of The Gleaner certainly felt the effects of COVID this Nutcracker The Dubuque City season. Noah Ripperger, Youth Ballet’s production ‘23, dancing the role of of The Nutcracker is an the Nutcracker, said, “The annual holiday tradition quality of the show will be for dancers and their fans. different; that’s not because Christmas would not of the dancers’ talents. It’s feel the same without the simply because we are in whimsical storytelling, a pandemic and have had beautiful dancing, colorful a hard time working with costumes, and familiar restrictions.” melodies. Though the company This year, the high typically has a strict one- miss policy for rehearsals, number of COVID cases in Falling into the 2020 Nutcracker the Dubuque community that has been altered this created fear that the ballet The Nutcracker cast of 2019 performing their last snow dance routine during last year’s holi- year to allow for proper would be cancelled. day season. quarantines. Often mul- However, the company’s “I’m looking forward to has sold out. Berning noted ences and are grateful that tiple dancers are missing directors were committed showing everyone what we that though it will feel the tradition continues this from each rehearsal, which to giving their dancers a have worked so hard on,” different to perform for a year. Senior Emilia Harris has made it difficult for the performance opportunity. said Berning. “I’m also glad much smaller audience, she said that watching dancers company to properly space They implemented pre- we can provide many peo- feels lucky that they are perform The Nutcracker as and rehearse group scenes. -

Santa Claus from Country to Country

Santa Claus from Country to Country Lesson topic: Various ways Santa is portrayed in different countries Content Concepts: -Learn about various Santa Claus legends United States, Belgium, Brazil, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, New Zealand, Romania, Russia, Netherlands, Spain, Chile. -Social Studies, history, map skills -Reading (list of library books) -Math problems -Science projects -Craft projects -Writing practice -Gaming skills -Music (list of Christmas CD’s) Proficiency levels: Grades 4 - 6 Information, Materials, Resources: Social Studies, History, and Map skills United States: The modern portrayal of Santa Claus frequently depicts him listening to the Christmas wishes of young children. Santa Claus (also known as Saint Nicholas, Saint Nick, Father Christmas, Kris Kringle, Santy or simply Santa) is a folklore figure in various cultures who distributes gifts to children, normally on Christmas Eve . Each name is a variation of Saint Nicholas , but refers to Santa Claus. In today's North American, European and worldwide celebration of Christmas, people young and old simply refer to the hero of the season as Santa , or Santa Claus. (Wikipedia) Conventionally, Santa Claus is portrayed as a kindly, round-bellied, merry, bespectacled white man in a red coat trimmed with white fur, with a long white beard . On Christmas Eve, he rides in his sleigh pulled by flying reindeer from house to house to give presents to children. To enter the house, Santa Claus comes down the chimney and exits through the fireplace . During the rest of the year he lives together with his wife Mrs. Claus and his elves manufacturing toys . Some modern depictions of Santa (often in advertising and popular entertainment) will show the elves and Santa's workshop as more of a processing and distribution facility, ordering and receiving the toys from various toy manufacturers from across the world. -

Rick Steves' European Christmas

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACTS: Rhonda Maronn, OPB Brooke Burdick, Rick Steves 503.977.7780 425.608.4233 [email protected] [email protected] RICK STEVES’ EUROPEAN CHRISTMAS A feast for the eyes, from one of public television’s top pledge drive hosts! PORTLAND, Ore., September 27, 2006 – After producing more than 100 travel shows, Rick Steves and his television crew finally celebrate Christmas in Europe. The result – a picturesque celebration in RICK STEVES’ EUROPEAN CHRISTMAS a co-production of Back Door Productions and Oregon Public Broadcasting. This colorful montage of the holiday’s rich history of traditions explores the sights and sounds of celebrations from Bath, Paris, Oslo, Burgundy and the traditions of Nürnberg, Salzburg and Tuscany in a European snapshot of Christmas. A consistent top performer in pledge drives through the years, Steves’ latest contribution, RICK STEVES’ EUROPEAN CHRISTMAS is sure to grab the attention of the wanderlust traveler and entice support for your public television station with a magnificent companion book, DVD and CD. From England to Norway, Burgundy to Bavaria, and Rome to the top of the Swiss Alps, RICK STEVES’ EUROPEAN CHRISTMAS gets you down on the carpet with wide-eyed children, up in the loft with the finest choirs, and into the kitchen with grandma and all her secrets. Experience traditional European Christmas like never before: from flaming puddings and minced pies in jolly old England to angelic girls’ choirs donning flickering crowns of candles in Olso. Christmas in Europe is a rich and fascinating mix of Christian and pre-Christian traditions; yule logs and mistletoe, shepherd’s bonfires and fondue, monastic chants and a Christmas yodel. -

100% 459 of 459 Respondents This Information Is Just to Help Interpret Results - No Personal Data Are Collected Answered the Question

Q01: First, some questions about you. Are you male or female? 100% 459 Of 459 Respondents This information is just to help interpret results - no personal data are collected answered the question 68 32 A1 Male 145 31.59 % A2 Female 314 68.41 % 459 people have answered the question. Q02: What is your age group: 100% A little bit more information to help interpret the results. Are you.... 459 Of 459 Respondents answered the question 29 29 9 21 8 5 0 0 A1 Under 12? 1 0.22 % A2 Teenager? 2 0.44 % A3 In your twenties? 22 4.79 % A4 In your thirties? 40 8.71 % A5 In your forties? 96 20.92 % A6 In your fifties? 131 28.54 % A7 In your sixties? 131 28.54 % A8 Over 70? 36 7.84 % 459 people have answered the question. Q03: And where do you live? 100% This question helps make sense of the answers - mistletoe species and customs vary from 459 Of 459 place to place Respondents answered the question 95 2 1 2 A1 Great Britain 437 95.21 % A2 Ireland 8 1.74 % A3 Mainland Europe 6 1.31 % Created by SurveyPirate.com A4 Elsewhere 10 2.18 % 459 people have answered the question. Q04: Now, the mistletoe questions... Do you use mistletoe each year at home at Christmas? 100% 459 Of 459 Respondents However you use it; hanging it up, carrying it with you in case of opportunity (!), sending it as a answered the gift... question 45 39 15 1 A1 Yes, every year 208 45.32 % A2 Some years, not always 179 39 % A3 Never 70 15.25 % A4 Not sure 3 0.65 % 459 people have answered the question. -

Wassailing Goes Back to Pre-Christian Times in a Tradition Meant to Bring Luck for the Coming Year

houses gave them drink, money and Christmas food. Christmas and money drink, them gave houses to the health of those they visited. In return, people in the the in people return, In visited. they those of health the to wassail bowl filled with spiced ale and sang and drank drank and sang and ale spiced with filled bowl wassail regions, the wassailers went from door to door, with a a with door, to door from went wassailers the regions, hael,’ meaning ‘drink and be healthy.’ In cider producing producing cider In healthy.’ be and ‘drink meaning hael,’ ‘waes hael.’ The assembled crowd would reply ‘drinc ‘drinc reply would crowd assembled The hael.’ ‘waes start of each year, the Saxon lord of the manor would shout shout would manor the of lord Saxon the year, each of start Old English term “waes hael,” meaning “be well.” At the the At well.” “be meaning hael,” “waes term English Old to bring luck for the coming year. Wassail gets its name from the the from name its gets Wassail year. coming the for luck bring to Wassailing goes back to pre-Christian times in a tradition meant meant tradition a in times pre-Christian to back goes Wassailing Wassailing goes back to pre-Christian times in a tradition meant to bring luck for the coming year. Wassail gets its name from the Old English term “waes hael,” meaning “be well.” At the start of each year, the Saxon lord of the manor would shout ‘waes hael.’ The assembled crowd would reply ‘drinc hael,’ meaning ‘drink and be healthy.’ In cider producing regions, the wassailers went from door to door, with a wassail bowl filled with spiced ale and sang and drank to the health of those they visited. -

Davies2012.Pdf (Link Is External)

Gwilym Davies, Wassail all over the place, Mummers Unconvention, Bath, 2012. Wassail all over the place. Mumming plays and wassailing are both English winter customs, in many cases being performed in the same locality or nearby. The aim of this paper is to explore the symbiosis between these two customs in the collected tradition, with particular reference to Gloucestershire, and then to describe the current situation post the folk revival. The Mumming tradition Firstly, let us consider the mumming tradition in Gloucestershire from the collected sources. We have 60 complete texts, fairly evenly spread throughout the county, as well as many fragments and references to uncollected plays. To describe the event in brief, a group of men from a locality or family group, typically from the labouring class, would rehearse a Combat Hero play and then, starting a few days before Christmas and going up to Christmas Eve, Boxing Day or perhaps around the New Year (but never Christmas Day), would perform their play from house to house, farm to farm, even calling at some business enterprises where they considered the collection would be profitable. In many cases, the performance concluded with a song, sometimes requesting money, food or drink, as collected in Sherborne in about 1930; Good master and mistress, both sit by the fire, Put your hand in your pocket we pray and desire Put your hand in your pocket and pull out your purse, For a little of something will do us no hurt Chorus Sing fa the ro raddie, sing fa the ro raddie Sing fa the ro raddie ay-aye. -

Mistletoes of North American Conifers

United States Department of Agriculture Mistletoes of North Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station American Conifers General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-98 September 2002 Canadian Forest Service Department of Natural Resources Canada Sanidad Forestal SEMARNAT Mexico Abstract _________________________________________________________ Geils, Brian W.; Cibrián Tovar, Jose; Moody, Benjamin, tech. coords. 2002. Mistletoes of North American Conifers. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS–GTR–98. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 123 p. Mistletoes of the families Loranthaceae and Viscaceae are the most important vascular plant parasites of conifers in Canada, the United States, and Mexico. Species of the genera Psittacanthus, Phoradendron, and Arceuthobium cause the greatest economic and ecological impacts. These shrubby, aerial parasites produce either showy or cryptic flowers; they are dispersed by birds or explosive fruits. Mistletoes are obligate parasites, dependent on their host for water, nutrients, and some or most of their carbohydrates. Pathogenic effects on the host include deformation of the infected stem, growth loss, increased susceptibility to other disease agents or insects, and reduced longevity. The presence of mistletoe plants, and the brooms and tree mortality caused by them, have significant ecological and economic effects in heavily infested forest stands and recreation areas. These effects may be either beneficial or detrimental depending on management objectives. Assessment concepts and procedures are available. Biological, chemical, and cultural control methods exist and are being developed to better manage mistletoe populations for resource protection and production. Keywords: leafy mistletoe, true mistletoe, dwarf mistletoe, forest pathology, life history, silviculture, forest management Technical Coordinators_______________________________ Brian W. Geils is a Research Plant Pathologist with the Rocky Mountain Research Station in Flagstaff, AZ. -

December 2014

Bowerston Public Library Newsletter DECEMBER 2014 Best Sellers B o w e r s t o n P u b lic L ib r a r y FICTION BEST SELLERS NON-FICTION BEST GRAY MOUNTAIN SELLERS Library Board of Trustees: John Grisham LEAVING TIME KILLING PATTON President: William W. Titley Jodi Picoult Bill O’Reilley and Martin Dugard DEADLINE Vice-President: Susan Cook John Sanford 13 HOURS DESERT GOD Mitchell Zuckoff Secretary: Kathy Bower Wilbur Smith LILA WHAT IF Les Berg Marilynne Robinson Randall Munroe BURN Kevin Willoughby James Patterson DIARY OF A MAD DIVA SHOPAHOLIC TO THE STARS Joan Rivers Dianne Cole Sophie Kinsella Logan Putnam THE HURRICANE SISTERS Dorothea Benton Frank We Will Be Closed THE MATCHMAKER Elin Hilderbrand THE INVENTION OF WINGS CHRISTMAS EVE Sue Monk Kidd & CHRISTMAS DAY Library Hours Monday 10 - 8 Tuesday 10 - 5 Wednesday 10 - 5 Thursday 10 - 8 Friday 10 - 2 Saturday 9 - 1 Sunday Closed DVD’S BOOKS Place these Place on Hold NOW!! New Books on Hold Library or from your home computer at www.bowerstonlibrary.org STORY HOUR FIRST WEDNESDAY Available for Reserve Now of the Month Havanna Storm by Clive Cussler The Patmos Deception by Davis Bunn 10:30 - 11:15 Christopher’s Diary : Secrets of Foxworth by V.C Andrews Winter Street by Elin Hilderbrand Full Measure by T. Jefferson Parker Toddlers and preschoolers: Join us for a Us by David Nicholls fun-filled morning of stories, activities, Wyoming Strong by Diana Palmer crafts. Children will learn important so- Host by Robin Cook cial interaction skills while they enjoy A.D 30 by Ted Dekker making new friends. -

The Nutcracker by E.T.A

The Nutcracker By E.T.A. Hoffman Act I It’s a cozy Christmas Eve at the Stahlbaum’s house. Their house is decorated with Christmas ornaments, wreaths, stockings, mistletoe and in the center of it all, a majestic Christmas tree. As the Stahlbaum’s prepare for their annual Christmas party, their children, Fritz and Clara, wait anxiously for their families and friends to arrive. When the guests finally appear, the party picks up with dancing and celebration. A mysterious guest arrives dressed in dark clothing, nearly frightening Fritz, but not Clara. Clara knows he is Godfather Drosselmeyer, the toymaker. His surprise arrival is warmly accepted and all the children dance and carry on with laughter. The celebration is interrupted again when Drosselmeyer reveals to the children that he has brought them gifts. The girls receive beautiful china dolls and the boys receive bugles. Fritz is given a beautiful drum, but Clara is given the best gift of all, the Nutcracker. Fritz grows jealous, snatches the Nutcracker from Clara and plays a game of toss with the other boys. It isn't long until the Nutcracker breaks. Clara is upset, but Drosselmeyer fixes it with a handkerchief. Drosselmeyer’s nephew offers Clara a small make-shift bed under the Christmas tree for her injured Nutcracker. The party grows late and the children become sleepy. Everyone generously thanks the Stahlbaum’s before they leave. As Clara’s family retires to bed, she checks on her Nutcracker one last time and ends up falling asleep under the Christmas tree with the Nutcracker in her arms. -

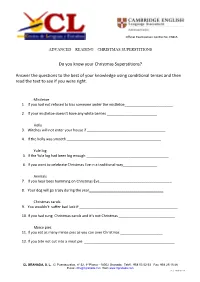

Advanced – Reading – Christmas Superstitions

Official Examination Centre No. ES815 ADVANCED – READING – CHRISTMAS SUPERSTITIONS Do you know your Christmas Superstitions? Answer the questions to the best of your knowledge using conditional tenses and then read the text to see if you were right. Mistletoe 1. If you had not refused to kiss someone under the mistletoe________________________ 2. If your mistletoe doesn’t have any white berries _________________________ Holly 3. Witches will not enter your house if _______________________________________ 4. If the holly was smooth _______________________________________________ Yule log 5. If the Yule log had been big enough _________________________________________ 6. If you want to celebrate Christmas Eve in a traditional way_________________ Animals 7. If you hear bees humming on Christmas Eve____________________________________ 8. Your dog will go crazy during the year_____________________________________ Christmas carols 9. You wouldn’t suffer bad luck if _________________________________________________ 10. If you had sung Christmas carols and it’s not Christmas ____________________________ Mince pies 11. If you eat as many mince pies as you can over Christmas _____________________ 12. If you bite not cut into a meat pie _____________________________________________ CL GRANADA, S. L. C/ Puentezuelas, nº 32, 1ª Planta - 18002 Granada. Teléf.: 958 53 52 53 Fax: 958 25 15 46 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.clgranada.com Rev: 10/01-01-17 Official Examination Centre No. ES815 mistletoe In the original superstition, the one who avoids a kiss under the mistletoe will have bad luck but the man is meant to present the kissee with a mistletoe berry. Once the berries are gone, the kissing stops holly Holly is protective magic against witches and lightning and is brought in during the holiday season for that purpose.