The Passage of the Arnold Expedition Through Skowhegan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIONAL HISTORIC\LANDMARKS Network

NATIONAL HISTORIC\LANDMARKS Network Volume III, No. National Park Service, National Historic Landmarks Program Summer zooo Angel Island Immigration Station: Major Steps for Preserving a National Treasure Stewards by Daniel Quan by Mary L. Leach ROM 1910 TO 1940, ANGEL ISLAND Station was designated a National Historic Immigration Station, located in the Landmark in 1997. HE NATIONAL HISTORIC FSan Francisco Bay, was the primary The immigration station is part of Angel Landmark Stewards Association if entry for immigrants arriving on Island State Park, a unit of the California T (NHLSA) has taken the first the West Coast. Its most significant role Department of Parks and Recreation. The major steps in becoming a national organi was as a detainment center for Chinese movement to preserve and restore it has zation. Its Articles of Incorporation and its immigrants, who were subject to exclusion been led by the Angel Island Immigration Bylaws were recently filed in the ary immigration laws from 1882 until Station Foundation, a volunteer group that Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. In addi 1943. While detained, many Chinese successfully lobbied for $250,000 in state tion, its 501(c)(3) application for recogni immigrants carved poignant, emotional funds for initial stabilization of the deten tion as a charitable organization is being poems into the walls of the detention bar tion barracks, thereby allowing the building finalized for submission to the Internal racks. Over 100 poems have been docu to be opened to the public. Since then, no Revenue Service. In the meantime, the mented, many of which are still visible other public or private funds have been University of Maryland Foundation has today. -

Seven External Factors That Adversely Influenced Benedict Arnold’S 1775 Expedition to Quebec

SEVEN EXTERNAL FACTORS THAT ADVERSELY INFLUENCED BENEDICT ARNOLD’S 1775 EXPEDITION TO QUEBEC Stephen Darley Introduction Sometime in August of 1775, less than two months after taking command of the Continental Army, Commander-in-Chief George Washington made the decision to send two distinct detachments to invade Canada with the objective of making it the fourteenth colony and depriving the British of their existing North American base of operations. The first expedition, to be commanded by Major General Philip Schuyler of Albany, New York, was to start in Albany and take the Lake Champlain-Richelieu River route to Montreal and then on to Quebec. The second expedition, which was assigned to go through the unknown Maine wilderness, was to be commanded by Colonel Benedict Arnold of New Haven, Connecticut.1 What is not well understood is just how much the outcome of Arnold’s expedition was affected by seven specific factors each of which will be examined in this article. Sickness, weather and topography were three external factors that adversely affected the detachment despite the exemplary leadership of Arnold. As if the external factors were not enough, the expedition’s food supply became badly depleted as the march went on. The food shortage was directly related to the adverse weather conditions. However, there were two other factors that affected the food supply and the ability of the men to complete the march. These factors were the green wood used to manufacture the boats and the return of the Lieutenant Colonel Roger Enos Division while the expedition was still in the wilderness. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet COLBURN HOUSE STATE HISTORIC SITE KENNEBEC COUNTY

rr r * { ' \ NPS Form 10-900 jv OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructionsTrts£tow to Complete/the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking VSn^he apj>ro0riate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable^" Fgf functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. PlacxNfdditional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Colburn House State Historic Site other names/site number 2. Location street & number Arnold Road. Old Route 27(.1 mi. south of northern intersection with Rt. 27) N/A not for publication city or town.............Pittston... N/A vicinity state Maine__________ code ME county Kennebec____ code 011___ zip code 04435 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this E nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In rny opinion, the property B meets Ddoes not meet the National Register criteria. -

David Library of the American Revolution Guide to Microform Holdings

DAVID LIBRARY OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION GUIDE TO MICROFORM HOLDINGS Adams, Samuel (1722-1803). Papers, 1635-1826. 5 reels. Includes papers and correspondence of the Massachusetts patriot, organizer of resistance to British rule, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and Revolutionary statesman. Includes calendar on final reel. Originals are in the New York Public Library. [FILM 674] Adams, Dr. Samuel. Diaries, 1758-1819. 2 reels. Diaries, letters, and anatomy commonplace book of the Massachusetts physician who served in the Continental Artillery during the Revolution. Originals are in the New York Public Library. [FILM 380] Alexander, William (1726-1783). Selected papers, 1767-1782. 1 reel. William Alexander, also known as “Lord Sterling,” first served as colonel of the 1st NJ Regiment. In 1776 he was appointed brigadier general and took command of the defense of New York City as well as serving as an advisor to General Washington. He was promoted to major- general in 1777. Papers consist of correspondence, military orders and reports, and bulletins to the Continental Congress. Originals are in the New York Historical Society. [FILM 404] American Army (Continental, militia, volunteer). See: United States. National Archives. Compiled Service Records of Soldiers Who Served in the American Army During the Revolutionary War. United States. National Archives. General Index to the Compiled Military Service Records of Revolutionary War Soldiers. United States. National Archives. Records of the Adjutant General’s Office. United States. National Archives. Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty and Warrant Application Files. United States. National Archives. Revolutionary War Rolls. 1775-1783. American Periodicals Series I. 33 reels. Accompanied by a guide. -

Pownalbo Rough Court House the Lincoln County Cultural And

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Maine COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Lincoln INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) COMMON: /-^ . Pownalbo rough Courtt HoHouse AND/OR HISTORIC: STREET AND NUMBER: Cedar Grove Road CITY OR TOWN: Dresden COUNTY: X Maine 1 Lincoln CATEGORY ACCESS.BLE OWNERSH.P STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC D District |£] Building D P^lic Public Acquisition: H occupied seasonal [53 Restricted D Site Q] Structure S Private CD In Process D Unoccupied i — .n - • CD Unrestricted D Object D Both [ | Being Considered Lj Preservation work in progress n NO PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) \ | Agricultural | | Government [~~1 Park CD Transportation | | Commercial 1 1 Industrial [~] Private Residence n Other (Specify) JC] Educational 1 1 Mi itary Q Religious I | Entertainment CD Museum J£] Scientific OWNER'S NAME: The Lincoln County Cultural and Historical Society STREET AND NUMBER: Federal Street Cl TY OR TOWN: CODE Wise as set Maine -T8- COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Lincoln County Courthouse Lincoln OUNTY: STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Wiscasset Maine 1 8 TitI-E OF SURVEY: Historic American Buildings Survey DATE OF SURVEY: S Federal CD State | | County | | Loca DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: Library of Congress STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Washington D. C. 08 (Check One) [jjj| Excellent 1 Good CU Fair [~j Deteriorated a Ruins n Unexposed CONDITION (Check One) (Check One) D Altered E Unaltered D Moved [X) Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Plymouth Company Proprietors on April 13th, 1?61, voted to build, within the parade of Fort Shirley, a house forty-five feet long and foipty-four feet wide and three stories high, and that one room on the second story forty-five feet long and twenty feet wide be fitted with boxes and benches needful for holding courts. -

Hclassification

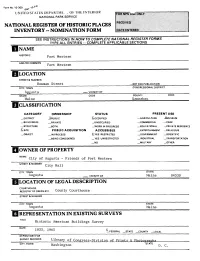

Form No. 10-300 ^ \0'1 ^ UNITED STATES DEPARTML. OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC Fort Western AND/OR COMMON Fort Western LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Bowman Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Augusta VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Maine Kennebec HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _D I STRICT -XPUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE _XMUSEUM _BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE X_SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME City of Augusta - Friends of Fort Western STREET* NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Augusta VICINITY OF Maine 04330 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Augusta Maine 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey DATE 1933, 1965 X^-FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress-Division of Prints & Photographs CITY, TOWN Washington STATE D. C, DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE X.GOOD _RUINS FALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE As built in 1754, Fort Western was comprised of an oblonged-shaped log stockade about 160 by 62 feet with two two-story log blockhouses located at opposite corners of the palisade, with a large two-and-one-half story log Main Building located within its walls. -

On Fellow Ous Ulletin

on fellow ous L g ulletinH e Volume No. A Newsletter of the Friends of the Longfellow House and the National Park Service June New Study ExaminesThe Song of HiawathaB as Controversial Bestseller atthew Gartner’s recent work on noted in his journal: “Some of the MH.W. Longfellow’s most popular newspapers are fierce and furious about poem asserts that The Song of Hiawatha was Hiawatha,” and a few weeks later, he both a bestseller and a subject of contro- wrote, “There is the greatest pother versy as soon as it was published, and about Hiawatha. It is violently assailed, quickly became a cultural phenomenon. and warmly defended.” The historian Gartner, who is writing a book called The William Prescott, a friend of Longfel- Poet Longfellow: A Cultural Interpretation, will low’s, wrote the poet from New York of present his findings and analysis this July “the hubbub that Hiawatha has kicked up at the Society for the History of Author- in the literary community.” ship, Reading, and Publishing. At the heart of the controversy lay When Hiawatha was first published in Longfellow’s decision to use a poetic it sold rapidly. With an initial print- meter called “trochaic dimeter.” The ing of five thousand volumes, four thou- George H. Thomas illustration, The Song of Hiawatha, London, nineteenth century was an age of great sand were already sold as of its November nationwide by , making it not only sensitivity to the art of prosody, or poetic publication date. By mid-December Longfellow’s best-selling poem ever, but, meter, and Longfellow surely knew Hiawa- eleven thousand volumes were in print. -

The Impact of Weather on Armies During the American War of Independence, 1775-1781 Jonathan T

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 The Force of Nature: The Impact of Weather on Armies during the American War of Independence, 1775-1781 Jonathan T. Engel Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE FORCE OF NATURE: THE IMPACT OF WEATHER ON ARMIES DURING THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE, 1775-1781 By JONATHAN T. ENGEL A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Jonathan T. Engel defended on March 18, 2011. __________________________________ Sally Hadden Professor Directing Thesis __________________________________ Kristine Harper Committee Member __________________________________ James Jones Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii This thesis is dedicated to the glory of God, who made the world and all things in it, and whose word calms storms. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Colonies may fight for political independence, but no human being can be truly independent, and I have benefitted tremendously from the support and aid of many people. My advisor, Professor Sally Hadden, has helped me understand the mysteries of graduate school, guided me through the process of earning an M.A., and offered valuable feedback as I worked on this project. I likewise thank Professors Kristine Harper and James Jones for serving on my committee and sharing their comments and insights. -

Environment and Culture in the Northeastern Americas During the American Revolution Daniel S

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Spring 5-11-2019 Navigating Wilderness and Borderland: Environment and Culture in the Northeastern Americas during the American Revolution Daniel S. Soucier University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Military History Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Other History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Soucier, Daniel S., "Navigating Wilderness and Borderland: Environment and Culture in the Northeastern Americas during the American Revolution" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2992. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/2992 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NAVIGATING WILDERNESS AND BORDERLAND: ENVIRONMENT AND CULTURE IN THE NORTHEASTERN AMERICAS DURING THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION By Daniel S. Soucier B.A. University of Maine, 2011 M.A. University of Maine, 2013 C.A.S. University of Maine, 2016 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School University of Maine May, 2019 Advisory Committee: Richard Judd, Professor Emeritus of History, Co-Adviser Liam Riordan, Professor of History, Co-Adviser Stephen Miller, Professor of History Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History Stephen Hornsby, Professor of Anthropology and Canadian Studies DISSERTATION ACCEPTANCE STATEMENT On behalf of the Graduate Committee for Daniel S. -

Appendix a Detailed Historical Research in Support of the Battle of the Clouds Project

Appendix A Detailed Historical Research in Support of the Battle of the Clouds Project Detailed Historical Research in Support of the Battle of the Clouds Project Robert Selig, Thomas J. McGuire, and Wade Catts, 2013 American Battlefield Protection Program Grant GA-2255-12-005 Prepared for Chester County Planning. John Milner Associates, Inc., West Chester, PA Compiled August 17, 2013 This document contains a compilation of technical questions posed by the County of Chester as part of a project funded by the American Battlefield Protection Program in 2013 to research and document the Battle of the Clouds which took place September 16, 1777. Nineteen questions were developed in order to produce a technical report containing details of the battle such as order of battle, areas of engagement, avenues of approach and retreat, and encampment areas. Research was conducted by John Milner Associates of West Chester under the guidance of Wade Catts and his research team consisting of Dr. Robert Selig and Thomas J. McGuire. Due to the obscurity of the battle and the lack of detailed first-hand accounts, some of the questions could not be answered conclusively and are so noted. Following is a summary of the questions: Intro Q1 - Were the troop strengths in this battle the same as Brandywine? After Brandywine Q2 - Did George Washington make his headquarters at the Stenton House in Germantown during the Continental encampment on September 13? Q3 - Were any troops left to cover Levering’s Ford or Matson’s Ford after Washington crossed back to the west -

BUSINESS in PHILADELPHIA DURING the BRITISH OCCUPATION, I777~I778

BUSINESS IN PHILADELPHIA DURING THE BRITISH OCCUPATION, I777~i778 HE USUAL historical narrative passes over the British occupa- tion of Philadelphia, during the winter season of 1777-78, Twith a brief statement of advent and departure, and the occa- sional observation that the royal forces lived comfortably, if not some- what extravagantly, in gross contrast with the sufferings of the con- tinentals nearby at Valley Forge. A pageant and festival, honoring Sir William Howe upon his departure in May, receive frequent men- tion, as do the military exploits of the rebel forces in the vicinity. Actually, the stay of the British troops in the Quaker city revealed the apathy of many inhabitants toward the revolution and pampered the cupidity of those who catered to the military. The presence of a large body of foreign troops profoundly affected the economic life of the community. Shortly after eight o'clock on the morning of September 26, 1777, Lord Cornwallis, commanding a British and Hessian force of grena- diers, dragoons, and artillery, approached the city of Philadelphia,1 and by ten o'clock his staff took formal possession of the rebel capital, as Captain John Montresor, chief engineer, observed, "amidst the acclamation of some thousands of the inhabitants mostly women and children."2 While to many Philadelphians the coming of the British army meant a separation from family, friends, and business, to others it promised relief from irksome exactions and arbitrary restrictions imposed by a Continental Congress whose authority was by no means generally accepted. As the summer of 1777 approached, this body or- dered all private stores of goods, especially flour and iron, to be re- moved beyond the city limits. -

Working Together to Preserve the Past

CUOURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT information for Parks, Federal Agencies, Trtoian Tribes, States, Local Governments, and %he Privale Sector <yt CRM TotLUME 18 NO. 7 1995 Working Together to Preserve the Past U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service Cultural Resources PUBLISHED BY THE VOLUME 18 NO. 7 1995 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Contents ISSN 1068-4999 To promote and maintain high standards for preserving and managing cultural resources Working Together DIRECTOR to Preserve the Past Roger G. Kennedy ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR Katherine H. Stevenson The Historic Contact in the Northeast EDITOR National Historic Landmark Theme Study Ronald M. Greenberg An Overview 3 PRODUCTION MANAGER Robert S. Grumet Karlota M. Koester A National Perspective 4 GUEST EDITOR Carol D. Shull Robert S. Grumet ADVISORS The Most Important Things We Can Do 5 David Andrews Lloyd N. Chapman Editor, NPS Joan Bacharach Museum Registrar, NPS The NHL Archeological Initiative 7 Randall J. Biallas Veletta Canouts Historical Architect, NPS John A. Bums Architect, NPS Harry A. Butowsky Shantok: A Tale of Two Sites 8 Historian, NPS Melissa Jayne Fawcett Pratt Cassity Executive Director, National Alliance of Preservation Commissions Pemaquid National Historic Landmark 11 Muriel Crespi Cultural Anthropologist, NPS Robert L. Bradley Craig W. Davis Archeologist, NPS Mark R. Edwards The Fort Orange and Schuyler Flatts NHL 15 Director, Historic Preservation Division, Paul R. Huey State Historic Preservation Officer, Georgia Bruce W Fry Chief of Research Publications National Historic Sites, Parks Canada The Rescue of Fort Massapeag 20 John Hnedak Ralph S. Solecki Architectural Historian, NPS Roger E. Kelly Archeologist, NPS Historic Contact at Camden NHL 25 Antoinette J.