Darshana Jolts the World Above – 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Demoting Pluto Presentation

WWhhaatt HHaappppeenneedd ttoo PPlluuttoo??!!!! Scale in the Solar System, New Discoveries, and the Nature of Science Mary L. Urquhart, Ph.D. Department of Science/Mathematics Education Marc Hairston, Ph.D. William B. Hanson Center for Space Sciences FFrroomm NNiinnee ttoo EEiigghhtt?? On August 24th Pluto was reclassified by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) as a “dwarf planet”. So what happens to “My Very Educated Mother Just Served Us Nine Pizzas”? OOffifficciiaall IAIAUU DDeefifinniittiioonn A planet: (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, and (c) has cleared the neighborhood around its orbit. A dwarf planet must satisfy only the first two criteria. WWhhaatt iiss SScciieennccee?? National Science Education Standards (National Research Council, 1996) “…science reflects its history and is an ongoing, changing enterprise.” BBeeyyoonndd MMnneemmoonniiccss Science is “ not a collection of facts but an ongoing process, with continual revisions and refinements of concepts necessary in order to arrive at the best current views of the Universe.” - American Astronomical Society AA BBiitt ooff HHiiststoorryy • How have planets been historically defined? • Has a planet ever been demoted before? Planet (from Greek “planetes” meaning wanderer) This was the first definition of “planet” planet Latin English Spanish Italian French Sun Solis Sunday domingo domenica dimanche Moon Lunae Monday lunes lunedì lundi Mars Martis -

The First Discovery of an Aster Astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi in St

DISCOVERYDOM OF THE MONTHEDITORIAL 27(96), January 1, 2015 ISSN 2278–5469 EISSN 2278–5450 Discovery The first discovery of an asteroid, Ceres by Italian astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi in January 1, 1801 Brindha V *Correspondence to: E-mail: [email protected] Publication History Received: 04 November 2014 Accepted: 01 December 2014 Published: 1 January 2015 Citation Brindha V. The first discovery of an asteroid, Ceres by Italian astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi in January 1, 1801. Discovery, 2015, 27(96), 1 Publication License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. General Note Article is recommended to print as color digital version in recycled paper. Ceres was the first object considered to be an asteroid. The first asteroid discovered was 1 Ceres, or Ceres on January 1, 1801, by Giuseppe Piazzi a monk and astronomer in Sicily. It was classified as a planet for a long time and is considered a dwarf planet later. Asteroids are small, airless rocky worlds revolving around the sun that are too small to be called planets. They are also known as planetoids or minor planets. Ceres is the closest dwarf planet to the Sun and is located in the asteroid belt making it the only dwarf planet in the inner solar system. Ceres rotates on its axis every 9 hours and 4 minutes. In 2006, the International Astronomical Union voted to restore the planet designation to Ceres, decreeing that it qualifies as a dwarf planet. It does have some planet-like characteristics, including an interior that is separated into crust, mantle and core. -

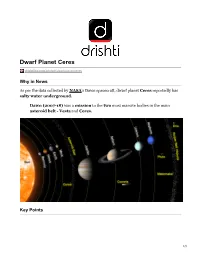

Dwarf Planet Ceres

Dwarf Planet Ceres drishtiias.com/printpdf/dwarf-planet-ceres Why in News As per the data collected by NASA’s Dawn spacecraft, dwarf planet Ceres reportedly has salty water underground. Dawn (2007-18) was a mission to the two most massive bodies in the main asteroid belt - Vesta and Ceres. Key Points 1/3 Latest Findings: The scientists have given Ceres the status of an “ocean world” as it has a big reservoir of salty water underneath its frigid surface. This has led to an increased interest of scientists that the dwarf planet was maybe habitable or has the potential to be. Ocean Worlds is a term for ‘Water in the Solar System and Beyond’. The salty water originated in a brine reservoir spread hundreds of miles and about 40 km beneath the surface of the Ceres. Further, there is an evidence that Ceres remains geologically active with cryovolcanism - volcanoes oozing icy material. Instead of molten rock, cryovolcanoes or salty-mud volcanoes release frigid, salty water sometimes mixed with mud. Subsurface Oceans on other Celestial Bodies: Jupiter’s moon Europa, Saturn’s moon Enceladus, Neptune’s moon Triton, and the dwarf planet Pluto. This provides scientists a means to understand the history of the solar system. Ceres: It is the largest object in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. It was the first member of the asteroid belt to be discovered when Giuseppe Piazzi spotted it in 1801. It is the only dwarf planet located in the inner solar system (includes planets Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars). Scientists classified it as a dwarf planet in 2006. -

NASA Spacecraft Nears Encounter with Dwarf Planet Ceres 4 March 2015

NASA spacecraft nears encounter with dwarf planet Ceres 4 March 2015 of 590 miles (950 kilometers), makes a full rotation every nine hours, and NASA is hoping for a wealth of data once the spacecraft's orbit begins. "Dawn is about to make history," said Robert Mase, project manager for the Dawn mission at NASA JPL in Pasadena, California. "Our team is ready and eager to find out what Ceres has in store for us." Experts will be looking for signs of geologic activity, via changes in these bright spots, or other features on Ceres' surface over time. The latest images came from Dawn when it was 25,000 miles (40,000 kilometers) away on February 25. This image was taken by NASA's Dawn spacecraft of dwarf planet Ceres on February 19, 2015 from a The celestial body was first spotted by Sicilian distance of nearly 29,000 miles astronomer Father Giuseppe Piazzi in 1801. "Ceres was initially classified as a planet and later called an asteroid. In recognition of its planet-like A NASA spacecraft called Dawn is about to qualities, Ceres was designated a dwarf planet in become the first mission to orbit a dwarf planet 2006, along with Pluto and Eris," NASA said. when it slips into orbit Friday around Ceres, the most massive body in the asteroid belt. Ceres is named after the Roman goddess of agriculture and harvests. The mission aims to shed light on the origins of the solar system 4.5 billion years ago, from its "rough The spacecraft on its way to circle it was launched and tumble environment of the main asteroid belt in September 2007. -

Aqueous Alteration on Main Belt Primitive Asteroids: Results from Visible Spectroscopy1

Aqueous alteration on main belt primitive asteroids: results from visible spectroscopy1 S. Fornasier1,2, C. Lantz1,2, M.A. Barucci1, M. Lazzarin3 1 LESIA, Observatoire de Paris, CNRS, UPMC Univ Paris 06, Univ. Paris Diderot, 5 Place J. Janssen, 92195 Meudon Pricipal Cedex, France 2 Univ. Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cit´e, 4 rue Elsa Morante, 75205 Paris Cedex 13 3 Department of Physics and Astronomy of the University of Padova, Via Marzolo 8 35131 Padova, Italy Submitted to Icarus: November 2013, accepted on 28 January 2014 e-mail: [email protected]; fax: +33145077144; phone: +33145077746 Manuscript pages: 38; Figures: 13 ; Tables: 5 Running head: Aqueous alteration on primitive asteroids Send correspondence to: Sonia Fornasier LESIA-Observatoire de Paris arXiv:1402.0175v1 [astro-ph.EP] 2 Feb 2014 Batiment 17 5, Place Jules Janssen 92195 Meudon Cedex France e-mail: [email protected] 1Based on observations carried out at the European Southern Observatory (ESO), La Silla, Chile, ESO proposals 062.S-0173 and 064.S-0205 (PI M. Lazzarin) Preprint submitted to Elsevier September 27, 2018 fax: +33145077144 phone: +33145077746 2 Aqueous alteration on main belt primitive asteroids: results from visible spectroscopy1 S. Fornasier1,2, C. Lantz1,2, M.A. Barucci1, M. Lazzarin3 Abstract This work focuses on the study of the aqueous alteration process which acted in the main belt and produced hydrated minerals on the altered asteroids. Hydrated minerals have been found mainly on Mars surface, on main belt primitive asteroids and possibly also on few TNOs. These materials have been produced by hydration of pristine anhydrous silicates during the aqueous alteration process, that, to be active, needed the presence of liquid water under low temperature conditions (below 320 K) to chemically alter the minerals. -

The Astronomical Work of Carl Friedrich Gauss

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector HISTORIA MATHEMATICA 5 (1978), 167-181 THE ASTRONOMICALWORK OF CARL FRIEDRICH GAUSS(17774855) BY ERIC G, FORBES, UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH, EDINBURGH EH8 9JY This paper was presented on 3 June 1977 at the Royal Society of Canada's Gauss Symposium at the Ontario Science Centre in Toronto [lj. SUMMARIES Gauss's interest in astronomy dates from his student-days in Gattingen, and was stimulated by his reading of Franz Xavier von Zach's Monatliche Correspondenz... where he first read about Giuseppe Piazzi's discovery of the minor planet Ceres on 1 January 1801. He quickly produced a theory of orbital motion which enabled that faint star-like object to be rediscovered by von Zach and others after it emerged from the rays of the Sun. Von Zach continued to supply him with the observations of contemporary European astronomers from which he was able to improve his theory to such an extent that he could detect the effects of planetary perturbations in distorting the orbit from an elliptical form. To cope with the complexities which these introduced into the calculations of Ceres and more especially the other minor planet Pallas, discovered by Wilhelm Olbers in 1802, Gauss developed a new and more rigorous numerical approach by making use of his mathematical theory of interpolation and his method of least-squares analysis, which was embodied in his famous Theoria motus of 1809. His laborious researches on the theory of Pallas's motion, in whi::h he enlisted the help of several former students, provided the framework of a new mathematical formu- lation of the problem whose solution can now be easily effected thanks to modern computational techniques. -

The Minor Planet Bulletin

THE MINOR PLANET BULLETIN OF THE MINOR PLANETS SECTION OF THE BULLETIN ASSOCIATION OF LUNAR AND PLANETARY OBSERVERS VOLUME 35, NUMBER 3, A.D. 2008 JULY-SEPTEMBER 95. ASTEROID LIGHTCURVE ANALYSIS AT SCT/ST-9E, or 0.35m SCT/STL-1001E. Depending on the THE PALMER DIVIDE OBSERVATORY: binning used, the scale for the images ranged from 1.2-2.5 DECEMBER 2007 – MARCH 2008 arcseconds/pixel. Exposure times were 90–240 s. Most observations were made with no filter. On occasion, e.g., when a Brian D. Warner nearly full moon was present, an R filter was used to decrease the Palmer Divide Observatory/Space Science Institute sky background noise. Guiding was used in almost all cases. 17995 Bakers Farm Rd., Colorado Springs, CO 80908 [email protected] All images were measured using MPO Canopus, which employs differential aperture photometry to determine the values used for (Received: 6 March) analysis. Period analysis was also done using MPO Canopus, which incorporates the Fourier analysis algorithm developed by Harris (1989). Lightcurves for 17 asteroids were obtained at the Palmer Divide Observatory from December 2007 to early The results are summarized in the table below, as are individual March 2008: 793 Arizona, 1092 Lilium, 2093 plots. The data and curves are presented without comment except Genichesk, 3086 Kalbaugh, 4859 Fraknoi, 5806 when warranted. Column 3 gives the full range of dates of Archieroy, 6296 Cleveland, 6310 Jankonke, 6384 observations; column 4 gives the number of data points used in the Kervin, (7283) 1989 TX15, 7560 Spudis, (7579) 1990 analysis. Column 5 gives the range of phase angles. -

THE ASTEROIDS and THEIR DISCOVERERS Rock Legends

PAUL MURDIN THE ASTEROIDS AND THEIR DISCOVERERS Rock Legends The Asteroids and Their Discoverers More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/4097 Paul Murdin Rock Legends The Asteroids and Their Discoverers Paul Murdin Institute of Astronomy University of Cambridge Cambridge , UK Springer Praxis Books ISBN 978-3-319-31835-6 ISBN 978-3-319-31836-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-31836-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016938526 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Cover design: Frido at studio escalamar Printed on acid-free paper This Springer imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Springer International Publishing AG Switzerland Acknowledgments I am grateful to Alan Fitzsimmons for taking and supplying the picture in Fig. -

Appendix 1 897 Discoverers in Alphabetical Order

Appendix 1 897 Discoverers in Alphabetical Order Abe, H. 22 (7) 1993-1999 Bohrmann, A. 9 1936-1938 Abraham, M. 3 (3) 1999 Bonomi, R. 1 (1) 1995 Aikman, G. C. L. 3 1994-1997 B¨orngen, F. 437 (161) 1961-1995 Akiyama, M. 14 (10) 1989-1999 Borrelly, A. 19 1866-1894 Albitskij, V. A. 10 1923-1925 Bourgeois, P. 1 1929 Aldering, G. 3 1982 Bowell, E. 563 (6) 1977-1994 Alikoski, H. 13 1938-1953 Boyer, L. 40 1930-1952 Alu, J. 20 (11) 1987-1993 Brady, J. L. 1 1952 Amburgey, L. L. 1 1997 Brady, N. 1 2000 Andrews, A. D. 1 1965 Brady, S. 1 1999 Antal, M. 17 1971-1988 Brandeker, A. 1 2000 Antonini, P. 25 (1) 1996-1999 Brcic, V. 2 (2) 1995 Aoki, M. 1 1996 Broughton, J. 179 1997-2002 Arai, M. 43 (43) 1988-1991 Brown, J. A. 1 (1) 1990 Arend, S. 51 1929-1961 Brown, M. E. 1 (1) 2002 Armstrong, C. 1 (1) 1997 Broˇzek, L. 23 1979-1982 Armstrong, M. 2 (1) 1997-1998 Bruton, J. 1 1997 Asami, A. 5 1997-1999 Bruton, W. D. 2 (2) 1999-2000 Asher, D. J. 9 1994-1995 Bruwer, J. A. 4 1953-1970 Augustesen, K. 26 (26) 1982-1987 Buchar, E. 1 1925 Buie, M. W. 13 (1) 1997-2001 Baade, W. 10 1920-1949 Buil, C. 4 1997 Babiakov´a, U. 4 (4) 1998-2000 Burleigh, M. R. 1 (1) 1998 Bailey, S. I. 1 1902 Burnasheva, B. A. 13 1969-1971 Balam, D. -

Mini Planet' with Water Ice 8 September 2005

Largest Asteroid May Be 'Mini Planet' With Water Ice 8 September 2005 Observations of 1 Ceres, the largest known From those snapshots, the astronomers determined asteroid, have revealed that the object may be a that the asteroid has a nearly round body. The "mini planet," and may contain large amounts of diameter at its equator is wider than at its poles. pure water ice beneath its surface. Computer models show that a nearly round object The observations by NASA's Hubble Space like Ceres has a differentiated interior, with denser Telescope also show that Ceres shares material at the core and lighter minerals near the characteristics of the rocky, terrestrial planets like surface. All terrestrial planets have differentiated Earth. Ceres' shape is almost round like Earth's, interiors. Asteroids much smaller than Ceres have suggesting that the asteroid may have a not been found to have such interiors. "differentiated interior," with a rocky inner core and a thin, dusty outer crust. The astronomers suspect that water ice may be buried under the asteroid's crust because the "Ceres is an embryonic planet," said Lucy A. density of Ceres is less than that of the Earth's McFadden of the Department of Astronomy at the crust, and because the surface bears spectral University of Maryland, College Park and a evidence of water-bearing minerals. They estimate member of the team that made the observations. that if Ceres were composed of 25 percent water, it "Gravitational perturbations from Jupiter billions of may have more water than all the fresh water on years ago prevented Ceres from accreting more Earth. -

History of the Observatory

HistoryHistory ofof thethe ObservatoryObservatory The foundation: Giuseppe Piazzi The foundation of the Astronomical Observatory in Palermo took place during the blissful time of the Bourbon reformism embodied in Sicily by the vice- roys Caracciolo and Caramanico. The establishment of a chair for Astronomy in Palermo – and the resulting foundation of an astro- nomical Observatory – had been part of a wide re- launching program for scientific culture, which also included the realization of a botanical garden and an anatomical theatre. In December 1786 the "Deputazione de' Regi Studi" (the early name of the University of Palermo) proposed to the Viceroy Prince of Caramanico the appointment of Giuseppe Piazzi (1746 - 1826), cleric regular of the order of the Theatines, as chair of Astronomy. Even if he wasn't an astronomer – as a matter of fact he was an unknown Lecturer of Mathematics – Piazzi proved to be the right person in the right place at the right time, capable of mak- ing Palermo one of the best astronomical research centres in the whole of Europe. Almost concurrently with his appointment, Piazzi was allowed to travel to Paris and London to get accustomed to practical astronomy. During his two years abroad he became acquainted with the most renownedd French and English astronomers, and, Title page of the first edition of Piazzi’s star catalogue most importantly, he developed a sound scientific program for the forthcoming building of the Obser- vatory and obtained the most suitable instruments for this purpose. Among these, the notable Rams- den's Circle, a masterpiece of the English 18th cen- tury precision mechanics, designed to improve ac- curacy in the measurement of the position of celes- tial bodies. -

Asteroid Masses and Improvement with Gaia

A&A 472, 1017–1027 (2007) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20077479 & c ESO 2007 Astrophysics Asteroid masses and improvement with Gaia S. Mouret1,D.Hestroffer1, and F. Mignard2 1 IMCCE, UMR CNRS 8028, Paris observatory, 77 Av. Denfert-Rochereau, 75014 Paris, France e-mail: [mouret;hestroffer]@imcce.fr 2 OCA/Cassiopée, UMR CNRS 6062, Nice observatory, Le Mont Gros, BP 4229, 06304 Nice Cedex 4, France e-mail: [email protected] Received 14 March 2007 / Accepted 18 May 2007 ABSTRACT Context. The ESA astrometric mission Gaia, due for launch in late 2011, will observe a very large number of asteroids (∼350 000 brighter than V = 20) with an unprecedented positional precision (at the sub-milliarcsecond level). Aims. Gaia will yield masses of the hundred largest asteroids from gravitational perturbations during close approaches with target asteroids. The objective is to develop a global method to obtain these masses which will use simultaneously all perturbers together with their target asteroids. In this paper, we outline the numerical and statistical methodology and show how to estimate the accuracy. Methods. The method that we use is the variance analysis from the formulation of observed minus calculated position (O−C). We as- sume a linear relationship between the (O−C) and the fitted parameters which are the initial position and velocity of the asteroids and the masses of perturbers. The matrix giving the partial derivatives with respect to the positions and masses is computed by numerical integration of the variational equations. Results. We show that with Gaia it will be possible to derive more than 100 masses of minor planets 42 of which with a precision better than 10%.