What Is Missionary Aestheticism? an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Chapter Will Demonstrate How Anglo-Catholicism Sought to Deploy

Building community: Anglo-Catholicism and social action Jeremy Morris Some years ago the Guardian reporter Stuart Jeffries spent a day with a Salvation Army couple on the Meadows estate in Nottingham. When he asked them why they had gone there, he got what to him was obviously a baffling reply: “It's called incarnational living. It's from John chapter 1. You know that bit about 'Jesus came among us.' It's all about living in the community rather than descending on it to preach.”1 It is telling that the phrase ‘incarnational living’ had to be explained, but there is all the same something a little disconcerting in hearing from the mouth of a Salvation Army officer an argument that you would normally expect to hear from the Catholic wing of Anglicanism. William Booth would surely have been a little disconcerted by that rider ‘rather than descending on it to preach’, because the early history and missiology of the Salvation Army, in its marching into working class areas and its street preaching, was precisely about cultural invasion, expressed in language of challenge, purification, conversion, and ‘saving souls’, and not characteristically in the language of incarnationalism. Yet it goes to show that the Army has not been immune to the broader history of Christian theology in this country, and that it too has been influenced by that current of ideas which first emerged clearly in the middle of the nineteenth century, and which has come to be called the Anglican tradition of social witness. My aim in this essay is to say something of the origins of this movement, and of its continuing relevance today, by offering a historical re-description of its origins, 1 attending particularly to some of its earliest and most influential advocates, including the theologians F.D. -

The Fabians Could Only Have Happened in Britain....In a Thoroughly Admirable Study the Mackenzies Have Captured the Vitality of the Early Years

THE famous circle of enthusiasts, reformers, brilliant eccentrics-Sha\y the Webbs, Wells-whose ideas and unconventional attitudes fashioned our modern world by Norman C&Jeanne MacKenzie AUTHORS OF H.G. Wells: A Biography PRAISE FOR Not quite a political party, not quite a pressure group, not quite a debating society, the Fabians could only have happened in Britain....In a thoroughly admirable study the MacKenzies have captured the vitality of the early years. Since much of this is anecdotal, it is immensely fun to read. Most im¬ portant, they have pinpointed (with¬ out belaboring) all the internal para¬ doxes of F abianism. —The Kirkus Reviews H. G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, Bertrand Russell, part of the outstandingly talented and paradoxical group that led the way to socialist Britain, are brought into brilliant human focus in this marvelously detailed and anecdote-filled por¬ trait of the original members of the Fabian Society—with a fresh assessment of their contributions to social thought. “The first Fabians,” said Shaw, were “missionaries among the savages,” who laid the ground¬ work for the Labour Party, and whose mis¬ sionary zeal and passionate enthusiasms carried them from obscurity to fame. This voluble and volatile band of middle-class in¬ tellectuals grew up in a period of liberating ideas and changing morals, influenced by (continued on back flap) c A / c~ 335*1 MacKenzie* Norman Ian* Ml99f The Fabians / Norman and Jeanne MacKenzie* - New York : Simon and Schuster, cl977* — 446 p** [8] leaves of plates : ill* - ; 24 cm* Includes bibliographical references and index* ISBN 0—671—22347—X : $11.95 1* Fabian Society, London* I* Title. -

London Borough of Lambeth

LONDON BOROUGH OF LAMBETH LAMBETH ARCHIVES DEPARTMENT Reference number IV/224 Title Morley College Covering dates 1888-2013 Physical extent 29 boxes & 2 volumes Creator Morley College Administrative history Morley College originated in the work of the Coffee Music Halls Company Ltd. who promoted temperance and the arts in London. The college was established by Emma Cons, a visionary and social reformer who fought to improve standards of London’s Waterloo district. In 1880, Cons, with the support of the Coffee Music Halls Company Ltd. leased what is now known as the ‘Old Vic’ theatre and created the Royal Victoria Coffee and Music Hall. In 1882 the hall began to host weekly lectures in which eminent scientists would address the public on a wide range of topics. The success of these lectures led to the establishment of Morley Memorial College for working men and women, named after Samuel Morley, a textile manufacturer, MP and philanthropist who contributed to Morley College. In the 1920s the college moved to Westminster Bridge Road where it remains today although it has since expanded and now includes Morley Gallery and Arts Studio and the Nancy Seear Building. The college has attracted eminent staff including composer Gustav Holst, Director of Music 1907- 1924, a post later filled by Sir Michael Kemp Tippet, 1940-1951. Other high profile personalities associated with the college include composer Ralph Vaughn Williams, writer Virginia Woolf and artist David Hockney. Acquisition or transfer information Collection acquired by Lambeth Archives between 1999-2007 as a gift. Acquisition numbers: 1999/11, 2002/30, 2003/13, 2006/11, 2007/23; ARC/2013/6,8. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pick, J.M. (1980). The interaction of financial practices, critical judgement and professional ethics in London West End theatre management 1843-1899. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/7681/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] THE INTERACTION OF FINANCIAL PRACTICES, CRITICAL JUDGEMENT AND PROFESSIONAL ETHICS IN LONDON WEST END THEATRE MANAGEMENT 1843 - 1899. John Morley Pick, M. A. Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the City University, London. Research undertaken in the Centre for Arts and Related Studies (Arts Administration Studies). October 1980, 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 4 Abstract 5 One. Introduction: the Nature of Theatre Management 1843-1899 6 1: a The characteristics of managers 9 1: b Professional Ethics 11 1: c Managerial Objectives 15 1: d Sources and methodology 17 Two. -

The Development of the Role of the Actor-Musician in Britain by British Directors Since the 1960’S

1 The Development of the Role of the Actor-Musician in Britain by British Directors Since the 1960’s Francesca Mary Greatorex Theatre and Performance Department Goldsmiths University of London A thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) 2 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Signed: ……………………………………………. 3 Acknowledgements This thesis could not have been written without the generosity of many individuals who were kind enough to share their knowledge and theatre experience with me. I have spoken with actors, musical directors, set designers, directors, singers, choreographers and actor-musicians and their names and testaments exist within the thesis. I should like to thank Emily Parsons the archivist for the Liverpool Everyman for all her help with my endless requests. I also want to thank Jonathan Petherbridge at the London Bubble for making the archive available to me. A further thank you to Rosamond Castle for all her help. On a sadder note a posthumous thank you to the director Robert Hamlin. He responded to my email request for the information with warmth, humour and above all, great enthusiasm for the project. Also a posthumous thank you to the actor, Robert Demeger who was so very generous with the information regarding the production of Ninagawa’s Hamlet in which he played Polonius. Finally, a big thank you to John Ginman for all his help, patience and advice. 4 The Development of the Role of the Actor-Musician in Britain by British Directors During the Period 1960 to 2000. -

5. Christian Socialism: a Phenomenon of Many Shapes and Variances

Debating Poverty Christian and Non-Christian Perspectives on the Social Question in Britain, 1880-1914 Dissertation zur Erlangung des philosophischen Doktorgrades an der Philosophischen Fakultät der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen vorgelegt von Angelika Maser aus München Göttingen 2009 1 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Bernd Weisbrod Seminar für Neuere und Neueste Geschichte Georg-August-Universität Göttingen 2. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Ilona Ostner Institut für Soziologie Georg-August-Universität Göttingen 3. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Jan-Ottmar Hesse Institut für Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte Georg-August-Universität Göttingen Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 04.08.2010 2 Eidesstattliche Erklärung Hiermit versichere ich an Eides statt, dass ich die eingereichte Dissertation „Debating Poverty. Christian and Non-Christian Perspectives on the Social Question in Britain, 1880-1914“ selbständig und ohne unerlaubte Hilfe verfasst habe. Anderer als der von mir angegebenen Hilfsmittel und Schriften habe ich mich nicht bedient. Alle wörtlich oder sinngemäß den Schriften anderer Autorinnen und Autoren entnommenen Stellen habe ich kenntlich gemacht. Die Abhandlung ist noch nicht veröffentlicht worden und noch nicht Gegenstand eines Promotionsverfahrens gewesen. Angelika Maser Göttingen, den 25.09.2009 3 Acknowledgements Like many doctoral theses, this one has taken a lot longer than planned. Along the way, many people have helped me with my work and supported me through difficult periods. To them it is owed that this study has finally become reality. I started work on this thesis as a scholar at the graduate research group „The Future of the European Social Model“ (DFG-Graduiertenkolleg „Die Zukunft des Europäischen Sozialmodells“) at the Georg-August-Universität Göttingen. I would like to thank the German Research Foundation for the scholarship I received. -

Journal 29-30 Pp1-156.Qxd

Article Title 131 Poverty, Socialism and Social Catholicism The Heart and Soul of Henry Manning Race Mathews In the early years of the twentieth century, the social teachings of the Catholic Church gave rise to a distinctive political philosophy that became known as Distributism. The basis of Distributism is the belief that a just social order can only be achieved through a much more widespread distribution of property. Distributism favours a ‘society of owners’, where property belongs to the many rather than the few, and correspondingly opposes the concentration of property in the hands of the rich, as under capitalism, or the state, as advocated by some socialists. In particular, ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange must be widespread. As defined by the prominent early Distributist, Cecil Chesterton: A Distributist is a man who desires that the means of production should, generally speaking, remain private property, but that their ownership should be so distributed that the determining mass of families — ideally every family — should have an efficient share therein. That is Distributism, and nothing else is Distributism ... ARENA journal no. 29/30, 2008 132 Race Mathews Distributism is quite as possible in an industrial or commercial as in an agrarian community.1 Distributism emerged as one element of the widespread revulsion and agony of conscience over poverty in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Britain. Its distinctive Catholic character stemmed from half a century of Catholic social thought, as drawn together by Pope Leo XIII in his encyclical letter Rerum Novarum in 1891, in part at the instigation of the great English Cardinal, Henry Manning. -

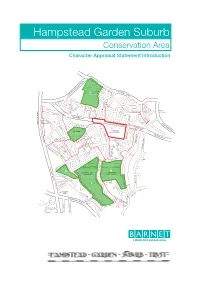

Hgstrust.Org London N11 1NP Tel: 020 8359 3000 Email: [email protected] (Add Character Appraisals’ in the Subject Line) Contents

Hampstead Garden Suburb Conservation Area Character Appraisal Statement Introduction For further information on the contents of this document contact: Urban Design and Heritage Team (Strategy) Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust Planning, Housing and Regeneration 862 Finchley Road First Floor, Building 2, London NW11 6AB North London Business Park, tel: 020 8455 1066 Oakleigh Road South, email: [email protected] London N11 1NP tel: 020 8359 3000 email: [email protected] (add character appraisals’ in the subject line) Contents Section 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Hampstead Garden Suburb 5 1.2 Conservation areas 5 1.3 Purpose of a character appraisal statement 5 1.4 The Barnet unitary development plan 6 1.5 Article 4 directions 7 1.6 Area of special advertisement control 7 1.7 The role of Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust 8 1.8 Distinctive features of this character appraisal 8 Section 2 Location and uses 10 2.1 Location 10 2.2 Uses and activities 11 Section 3 The historical development of Hampstead Garden Suburb 15 3.1 Early history 15 3.2 Origins of the Garden Suburb 16 3.3 Development after 1918 20 3.4 1945 to the present day 21 Section 4 Spatial analysis 22 4.1 Topography 22 4.2 Views and vistas 22 4.3 Streets and open spaces 24 4.4 Trees and hedges 26 4.5 Public realm 29 Section 5 Town planning and architecture 31 Section 6 Character areas 36 Hampstead Garden Suburb Character Appraisal Introduction 5 Section 1 Introduction 1.1 Hampstead Garden Suburb Hampstead Garden Suburb is internationally recognised as one of the finest examples of early twentieth century domestic architecture and town planning. -

Henrietta Barnett: Co-Founder of Toynbee Hall, Teacher, Philanthropist and Social Reformer

Henrietta Barnett: Co-founder of Toynbee Hall, teacher, philanthropist and social reformer. by Tijen Zahide Horoz For a future without poverty There was always “something maverick, dominating, Roman about her, which is rarely found in women, though she was capable of deep feeling.” n 1884 Henrietta Barnett and her husband Samuel founded the first university settlement, Toynbee Hall, where Oxbridge students could become actively involved in helping to improve life in the desperately poor East End Ineighbourhood of Whitechapel. Despite her active involvement in Toynbee Hall and other projects, Henrietta has often been overlooked in favour of a focus on her husband’s struggle for social reform in East London. But who was the woman behind the man? Henrietta’s work left an indelible mark on the social history of London. She was a woman who – despite the obstacles of her time – accomplished so much for poor communities all over London. Driven by her determination to confront social injustice, she was a social reformer, a philanthropist, a teacher and a devoted wife. A shrewd feminist and political activist, Henrietta was not one to shy away from the challenges posed by a Victorian patriarchal society. As one Toynbee Hall settler recalled, Henrietta’s “irrepressible will was suggestive of the stronger sex”, and “there was always something maverick, dominating, Roman about her, which is rarely found in women, though she was capable of deep feeling.”1 (Cover photo): Henrietta in her forties. 1. Creedon, A. ‘Only a Woman’, Henrietta Barnett: Social Reformer and Founder of Hampstead Garden Suburb, (Chichester: Phillimore & Co. LTD, 2006) 3 A fourth sister had “married Mr James Hinton, the aurist and philosopher, whose thought greatly influenced Miss Caroline Haddon, who, as my teacher and my friend, had a dynamic effect on my then somnolent character.” The Early Years (Above): Henrietta as a young teenager. -

These Strange Criminals: an Anthology Of

‘THESE STRANGE CRIMINALS’: AN ANTHOLOGY OF PRISON MEMOIRS BY CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTORS FROM THE GREAT WAR TO THE COLD WAR In many modern wars, there have been those who have chosen not to fight. Be it for religious or moral reasons, some men and women have found no justification for breaking their conscientious objection to vio- lence. In many cases, this objection has lead to severe punishment at the hands of their own governments, usually lengthy prison terms. Peter Brock brings the voices of imprisoned conscientious objectors to the fore in ‘These Strange Criminals.’ This important and thought-provoking anthology consists of thirty prison memoirs by conscientious objectors to military service, drawn from the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, and centring on their jail experiences during the First and Second World Wars and the Cold War. Voices from history – like those of Stephen Hobhouse, Dame Kathleen Lonsdale, Ian Hamilton, Alfred Hassler, and Donald Wetzel – come alive, detailing the impact of prison life and offering unique perspectives on wartime government policies of conscription and imprisonment. Sometimes intensely mov- ing, and often inspiring, these memoirs show that in some cases, indi- vidual conscientious objectors – many well-educated and politically aware – sought to reform the penal system from within either by publicizing its dysfunction or through further resistance to authority. The collection is an essential contribution to our understanding of criminology and the history of pacifism, and represents a valuable addition to prison literature. peter brock is a professor emeritus in the Department of History at the University of Toronto. -

Waterloo Guided Walks

WATERLOO GUIDED WALKS Waterloo is a historic and a fascinating neighbourhood, full of surprises, which can be discovered on these self-guided walks. Choose one or two routes through this historic part of South London, or add all four together to make one big circuit. Each section takes about 30 minutes without stops. WWW.WEAREWATERLOO.CO.UK @wearewaterloouk We are working with the Cross River Partnership through their Mayor’s Air Quality Funded programme Clean Air Better Business (CABB) to deliver air quality improvements and encourage active travel for workers, residents and visitors to the area. VICTORIAN WATERLOO Walk through the main iron gate (you are welcome to visit or attend a service) and skirt the church to the right, leaving by the gate hidden in the hedge right behind the building. Follow Secker Street left and right, In medieval times this area was desolate Lambeth Marsh, which only really came to life with the crossing Cornwall Road to Theed Street completion of Westminster Bridge in 1750. Then around a century later the first railways arrived, running above ground level on mighty brick viaducts. Start in Waterloo Station, under the four-faced clock suspended from the roof at the centre of the concourse, a popular meeting 4 spot for travellers for almost 80 years. Theed Street, Windmill Walk and Roupell Street This is one of London’s most atmospheric quarters, much fi lmed, with its nineteenth-century terraces, elegant streetlamps and steeply pitched roofs. The gallery on the corner of Theed Street was once a cello factory and the musical motif continues as you walk: the gate signed ‘The Warehouse’ is home to the London Festival Orchestra, which became independent in the 1980s and performs at major venues and festivals. -

Jn1:14) Editorial Our Lord

Volume 4, Issue 12 Christmas 2010 And the Word was Made Flesh... (Jn1:14) Editorial our Lord. As a newcomer, coming to know the history of the Church in the Continuum, I’ve come to terms with certain realities: Mistakes and misguided leadership has left its mark, but nevertheless, the Congress of St. Louis was an excellent beginning as seen in the presidential ad- dress of Perry Laukhuff and the Affirmation of St. Louis (published again for your reading). Wonder what happened to that fire for the Lord? Even after three decades of the legacy of the Congress of St. Louis we are found wanting in serving the Great Commission – more groups have emerged, more splits, more cafeteria Anglicanism com- promising the essentials of faith and practice. The Oxford movement was a lay movement to begin with, when laymen called attention of the Anglicans to their Catholic roots- magine you are rector of the church and the door bell continu- Catholic, in as much our faith and orders, an inheritance from the ously rings. On the other side of the door stand parents, desiring I Apostles, steeped in the two millennia of Christendom. baptism for their children. That’s what Fr. Kern experiences nearly every Within the Holy Catholic Church Anglican Rite, there have day. December 21, 2010 marked his 50th anniversary as a priest. This been efforts to remove laity and clergy from decision making process year alone Fr. Kern has administered the sacrament of baptism more by the adoption of the Apostolic Canons that deny them seat, voice than two hundred times.