Rediscovering Our Origins with Mikael Owunna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MIKAEL OWUNNA COSMOLOGIES September 17 – October 30, 2021

CLAMPART ! ❚ " FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MIKAEL OWUNNA COSMOLOGIES September 17 – October 30, 2021 Opening reception: Thursday, September 17, 2021 6:00 - 8:00 p.m. ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ClampArt is pleased to announce “Mikael Owunna | Cosmologies”—the artist’s first solo show with the gallery, and his first solo exhibition in New York City. Mikael Owunna’s series “Cosmologies” is an extension of his project titled “Infinite Essence” in which the artist responds to pervasive images in the media of Black people being shot and killed by the police. Owunna has begun a quest to recast the Black body as the cosmos and eternal. Hand-painting the bodies of his models with fluorescent paints, the artist augments a standard camera flash with an ultraviolet bandpass filter in order to pass only ultraviolet light through the lens. Shooting in total darkness, Owunna clicks the camera’s shutter, and for a fraction of a second, these Black bodies are illuminated as the universe, becoming celestial vessels of the divine. Owunna believes in order to bring forth the future destinies of African diasporic art, one must return to and revive its ancient origins. He grounds his work in the recovery, exploration, and modernization of West African knowledge 247 West 29th Street Ground Floor New York, NY 10001 tel 646.230.0020 e-mail [email protected] web www.clampart.com page three page two systems, specifically Dogon and Igbo cosmologies. These sacred sciences are poetically rendered systems of spiritual and empirical principles organized around the goal of divinizing human consciousness. Drawing on their influence, Owunna’s multi-media work similarly fuses art, science, and religion to provide a vehicle for Black transfiguration. -

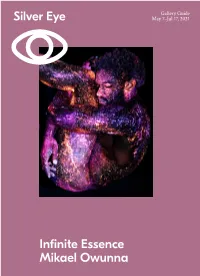

Infinite Essence

Gallery Guide May 7–Jul 17, 2021 Infinite Essence About Mikaelthe Exhibtion Owunna 1 About the Artist That Blackness is Most Black: Mikael Owunna’s Infinite Essence Mikael Owunna is a queer Nigerian-Swedish American multi-media artist and engineer based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Exploring the Upon glancing at photographs from Mikael Owunna’s Infinite Essence intersections of visual media with engineering, optics, Blackness, and series, you will immediately be enraptured by the incandescent figures that African cosmologies, his work seeks to elucidate an emancipatory vision of loom large in the center of these images, with gleaming surfaces of flesh possibility that pushes Black people beyond all boundaries, restrictions, and that seem struck with the residue of cosmic effluvia. Seeing these subjects frontiers. is a powerful reminder that most of the elements that make up the human Owunna’s work has been exhibited across Asia, Europe, and North body (carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen, among others) were forged in the America and been collected by institutions such as the Museum of Fine Arts cauldrons of distant stars and ejected across galaxies in massive explosions. Houston, Equal Justice Initiative, Duke University, and National Taiwan There are also intimations here of how primordial Africans invented time Museum. His work has also been featured in media ranging from the New itself through observation of celestial bodies and divined the meaning York Times to CNN, NPR, VICE, and The Guardian. He has lectured at of time through mythical depictions of figures superimposed upon star venues including Harvard Law School, World Press Photo (Netherlands), constellations in the night sky. -

About the Fulbright Program

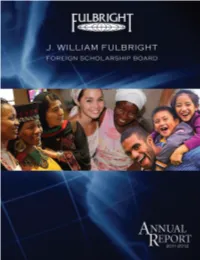

2011 - 2012 ANNUAL REPORT // 1 O U R C O V E R S T O R Y Fulbright scholars (from left) Mandisa Haarhoff and Wanda Sondiyazi of South Africa, and Shugofa Dastgeer of Afghanistan enjoy a cultural celebration at the 2012 University of Oklahoma-hosted Fulbright Gateway Orientation, where they also met Dr. Shelby Lewis of the J. William Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Board. Christina Briscoe, 2011-2012 U.S. Fulbright Student to Brazil (left), with Isabel Pacheco da Encarnação, the sister of her host mother. Ms. Briscoe researched reproductive health through interviews with women in the Ilha de Maré community. Working with Partners in Health Peru and living in a quilombola, a community formed by the descendants of escaped slaves, Ms. Briscoe focused her research on the representations of fibromyomas (benign uterine tumors) and their significance in the women’s lives as seen through encounters with the mainland biomedical community and in the generational knowledge imparted by their mothers. Ms. Briscoe is a graduate of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Mikael Owunna, Fulbright English Teaching Assistant at the Nan’ao and Wuyuan Elementary Schools in Yilan County, Luodong, Taiwan, in 2012, with Taiwanese aboriginal (Atayal) children. He collaborated with University of San Francisco Professor Christine Yeh, a Fulbright Senior Scholar at the National Taiwan Normal University, to develop and implement the “I am Atayal” project, promoting cultural pride and educational success among youths. Mr. Owunna is a graduate of Duke University in North Carolina, where he earned a B.S.E. with distinction in Biomedical Engineering and a B.A. -

Come You Spirits, Unsex Me Here: Contemporary Theatre and African Ceremonies As a Playground for Alternative Masculinities

1 Cotonou, Guelede 2019 Amsterdam Sunjata 2010 Come you Spirits, Unsex me Here: Contemporary Theatre and African Ceremonies as a Playground for Alternative Masculinities Javier López Piñón May 2021 2 3 Table of content 1. Abstract 4 2. Introduction 5 2.0 Composing a polyphonic/polyrhythmic argument: switching between the global north and the global majority 2.1 Masculinities and the stage 2.2 Masculinity studies and the black body 2.3 Hegemonic masculinity and homosexuality 2.4 Observations on gender role fluidity in West Africa 3. Three theatre seasons 2018-2020: masculinity intersecting with "race": 22 Giovanni's room/Heritage-Redo/Patroon/Een leven lang sex/ Between us/Allegria 3.1 A choice of five spectacles A. My heart into my mouth B. They/them C. White noise D. Making Men E. Notre Aujourd'hui Conclusions 31 Intermezzo: my gay gaze 33 Centrefold: Alternative masculinities in contemporary visual arts 38 4. This is a man's world: female masks, male dancers, cross-dressing 43 and gender identity exchange in West African performance practices 4.1 Gender identities: changing tunes 4.2.Gender and local performance practices: between impersonation and transformation I. Female impersonation II. Male to female transformation through masked dance A. Yorouba B. Baulé C. Chokwe D. Baga Igbo, Dan, Punu and others III. Identity obliteration through spiritual possession Hausa Conclusions 70 5. Intercultural playgrounds: performing alternative masculinities 73 Further research Bibliography and picture sources 83 Annexes 4 1. Abstract This thesis aims on one level to discuss masculinity intersecting with the way the male black body is presented on stage in recent theatre/dance performances and on another, it researches performance practices in West Africa for their portrayal of gender roles. -

Journal of the Pennsylvania Governor's School for the Sciences

Journal of the Pennsylvania Governor’s School for the Sciences Class of 2007 Volume 26, 2008 Mellon College of Science Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Journal of the Pennsylvania Governor's School for the Sciences Class of 2007 Volume 26, 2008 Copyright (c) 2008, by The Pennsylvania Governor's School for the Sciences and Carnegie Mellon University Permission is granted to quote from this journal with the customary acknowledgement of the source. To reprint a figure, table or other excerpt, requires, in addition, the consent of one of the original authors and notification of the PGSS. Journal of the PGSS Page iii Table of Contents Preface ..................................................................................................................................................1 Biology Team Projects Detection and Identification of Genetically Modified Soy (Glycine max) in Assorted Chocolate Food Products Bhaskar, Hanzok, Kedar, Lu, Oniskey, Punati, Qin, Reddy, Shoemaker, Singh, Viswanathan, Young .............................................................................................................................................5 Determination of the Midpoint of Adolescent Myelin Maturation as Measured by Change in Radial Diffusivity in Diffusion Tensor Imaging Baybars, Chang, Jiang, Onofrey, Ponnappa, Ponte, Ramgopal, Shen, Trevisan, Sheng, .........35 Biophysics Team Projects The Isotope Effects of Deuterium on the Enzyme Kinetics of Alcohol Dehydrogenase Alla, Bharathan, Comerci, Desai, Field, Gillis-Buck,