John Ashworth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategic Peacebuilding- the Role of Civilians and Civil Society in Preventing Mass Atrocities in South Sudan

SPECIAL REPORT Strategic Peacebuilding The Role of Civilians and Civil Society in Preventing Mass Atrocities in South Sudan The Cases of the SPLM Leadership Crisis (2013), the Military Standoff at General Malong’s House (2017), and the Wau Crisis (2016–17) NYATHON H. MAI JULY 2020 WEEKLY REVIEW June 7, 2020 The Boiling Frustrations in South Sudan Abraham A. Awolich outh Sudan’s 2018 peace agreement that ended the deadly 6-year civil war is in jeopardy, both because the parties to it are back to brinkmanship over a number S of mildly contentious issues in the agreement and because the implementation process has skipped over fundamental st eps in a rush to form a unity government. It seems that the parties, the mediators and guarantors of the agreement wereof the mind that a quick formation of the Revitalized Government of National Unity (RTGoNU) would start to build trust between the leaders and to procure a public buy-in. Unfortunately, a unity government that is devoid of capacity and political will is unable to address the fundamentals of peace, namely, security, basic services, and justice and accountability. The result is that the citizens at all levels of society are disappointed in RTGoNU, with many taking the law, order, security, and survival into their own hands due to the ubiquitous absence of government in their everyday lives. The country is now at more risk of becoming undone at its seams than any other time since the liberation war ended in 2005. The current st ate of affairs in the country has been long in the making. -

Humanitarian Bulletin South Sudan Issue 7 | 30 May 2016

Humanitarian Bulletin South Sudan Issue 7 | 30 May 2016 In this issue Health worker killed P.1 World Humanitarian Summit P.1 HIGHLIGHTS Needs increase in Wau P.2 • Humanitarian Coordinator condemns violence against Malaria response P.3 aid workers. Food insecurity in E. Equatoria P.3 • About 21,400 people are Addressing sexual violence P.4 displaced in the Greater A girl carries mosquito nets in Rejaf East. Photo: OCHA. Baggari area in Wau County. • Health partners are stepping up malaria preparedness and Humanitarian Coordinator condemns the killing of response efforts. • There are reports of a health worker increasing food insecurity in The Humanitarian Coordinator for South Sudan, Eugene Owusu, has strongly con- Eastern Equatoria. demned the tragic killing of Sister Veronika Racková, a Slovakian nun and medical doctor • UN Special Representative who was shot on 15 May 2016 in Yei, while on a humanitarian mission, and later suc- calls for action against sexual cumbed to her wounds. violence. “I am deeply saddened by this senseless act and send my deepest condolences to the family, friends and colleagues of Sister Veronika Racková,” said Mr. Owusu. “I welcome steps being taken by the authorities to bring the perpetrators to justice and urge them to FIGURES act swiftly.” No. of Sister Veronika Racková was driving an ambulance on her way back from a medical cen- Internally 1.69 million tre when she was attacked. Her death brings the number of aid workers killed in South Displaced Persons Sudan since the beginning of the conflict in December 2013 to 54. No. of “Violence against humanitarian workers and humanitarian assets is categorically unac- refugees in neighboring 720,394 ceptable and must stop,” said Mr. -

Remembrance 20001 Appleby 10

Speech by Rt Rev Anthony Poggo, Bishop of the Diocese Samaritan’s Purse generously contributed by building the pillars of Kajo-Keji at the Consecration of Emmanuel Cathedral and the roof of the Cathedral. The remaining work namely, the in Romoggi on Palm Sunday 17th April 2011 walls, windows & door shutters, floor screed and painting has been done using the contributions from the Christians of this Salutation Diocese supported by our friends within the Sudan as well as Your Grace the Most Rev Dr Daniel Deng Bul, the outside the Sudan. Our government leaders have given is Archbishop of the Episcopal Church of the Sudan tremendous support. Your Excellency, Ambassador Steven Wondu, Auditor General of the South Sudan We employed a contractor who agreed to undertake this work for Your Excellency the Commissioner of Kajo-Keji County a total cost of US$ 125,039, although the final figure will be more Representatives of partner organisations namely than US$ 130,000. We have raised over US$ 100,000 but still Samaritan Purse, SOMA and other organisations present have a shortfall of US$ 24,500. here. The Honourable Members of Parliament present here Fund Raising Religious Leaders from ECS and those representing We had a major fund raising event in Kajo-Keji on Sunday 28th other churches March 2010 where the Archbishop was the Guest of Honour. On Invited Guests from Juba, Yei, Uganda and other places that day, we raised an amount of US$ 7,721 with pledges made County Government Officials totalling to US$ 16,397. All other Guests Ladies and Gentlemen Fund Raising 2 In November 2010, we had a second fund function. -

The Religious Landscape in South Sudan CHALLENGES and OPPORTUNITIES for ENGAGEMENT by Jacqueline Wilson

The Religious Landscape in South Sudan CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR ENGAGEMENT By Jacqueline Wilson NO. 148 | JUNE 2019 Making Peace Possible NO. 148 | JUNE 2019 ABOUT THE REPORT This report showcases religious actors and institutions in South Sudan, highlights chal- lenges impeding their peace work, and provides recommendations for policymakers RELIGION and practitioners to better engage with religious actors for peace in South Sudan. The report was sponsored by the Religion and Inclusive Societies program at USIP. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Jacqueline Wilson has worked on Sudan and South Sudan since 2002, as a military reserv- ist supporting the Comprehensive Peace Agreement process, as a peacebuilding trainer and practitioner for the US Institute of Peace from 2004 to 2015, and as a Georgetown University scholar. She thanks USIP’s Africa and Religion and Inclusive Societies teams, Matthew Pritchard, Palwasha Kakar, and Ann Wainscott for their support on this project. Cover photo: South Sudanese gather following Christmas services at Kator Cathedral in Juba. (Photo by Benedicte Desrus/Alamy Stock Photo) The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. An online edition of this and related reports can be found on our website (www.usip.org), together with additional information on the subject. © 2019 by the United States Institute of Peace United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Avenue NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No. 148. First published 2019. -

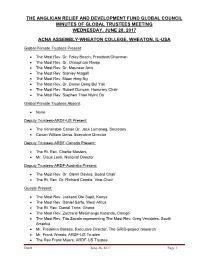

The Anglican Relief and Development Fund Global Council Minutes of Global Trustees Meeting Wednesday, June 28, 2017

THE ANGLICAN RELIEF AND DEVELOPMENT FUND GLOBAL COUNCIL MINUTES OF GLOBAL TRUSTEES MEETING WEDNESDAY, JUNE 28, 2017 ACNA ASSEMBLY-WHEATON COLLEGE, WHEATON, IL-USA Global Primate Trustees Present: • The Most Rev. Dr. Foley Beach, President/Chairman • The Most Rev. Dr. Onesphore Rwaje • The Most Rev. Dr. Mouneer Anis • The Most Rev. Stanley NtaGali • The Most Rev. Moon HinG NG • The Most Rev. Dr. Daniel DenG Bul Yak • The Most Rev. Robert Duncan, Honorary Chair • The Most Rev. Stephen Than Myint Oo Global Primate Trustees Absent: • None Deputy Trustees-ARDF-US Present: • The Venerable Canon Dr. Jack LumanoG, Secretary • Canon William Deiss, Executive Director Deputy Trustees-ARDF-Canada Present: • The Rt. Rev. Charlie Masters • Mr. Claus Lenk, National Director Deputy Trustees-ARDF-Australia Present: • The Most Rev. Dr. Glenn Davies, Board Chair • The Rt. Rev. Dr. Richard Condie, Vice-Chair Guests Present: • The Most Rev. Jackson Ole Sapit, Kenya • The Most Rev. Daniel Sarfo, West Africa • The Rt. Rev. Daniel Torto, Ghana • The Most Rev. Zacharie MasimanGo Katanda, Comgo • The Most Rev. Tito Zavala representinG The Most Rev. GreG Venables, South America • Mr. Frederick Barasa, Executive Director, The GRID-project research • Mr. Frank Woods, ARDF-US Trustee • The Rev Frank Myers, ARDF-US Trustee Draft June 28, 2017 Page 1 • Atty. Nancy Skancke, ARDF-US Trustee • The Rev. William Haley, ARDF-US Trustee • The Rev. David Hanke, Restoration AnGlican, ARDF-US Staff: • Christine Jones, Director of Mobilization • Jason Panella, Development Associate • Flora Galbraith, Office ManaGer Afternoon Prayer and Bible Study-The Most Rev. Dr. Glenn Davies • Philippians 2:1-18 o We see Jesus lower than the anGels now crowned with Glory o Consider others more important than yourselves o In ARDF’s work the poor will always be with us Call to Order and Welcome - The Most Rev. -

South Sudan Council of Churches, National Prayer Report

SOUTH SUDAN COUNCIL OF CHURCHES (SSCC) NATIONAL DAY OF PRAYERS SOUTH SUDAN COUNCIL OF CHURCHES NATIONAL PRAYER DR. JOHN GARANG’S MEMORIAL MAUSOLEUM FRIDAY - MARCH 10, 2017 08:00AM – 02:00PM (E.A.T) March 20, 2017 Report of the South Sudan Council of Churches Led National prayer 1 KEY SPEAKER (CHURCH, MUSLIMS & GOVERNMENT) South Sudan Council of Church: 1. His Grace Paulino LUKUDU LORO, Metropolitan Archbishop of Catholic Church of South Sudan – Juba (CCSS). 2. Archbishop Dr. Daniel DENG BUL, Archbishop and Primate, Episcopal Church of South Sudan/ and Sudan (ECSS/S). 3. Bishop Dr. Isaiah MAJOK DAU, General Overseer, Sudan Pentecostal Church (SPC), South Sudan – Juba. 4. Bishop Enock TOMBE, Episcopal Church of South Sudan/ Sudan – Rajaf Diocese (ECSS/S). 5. Bishop Dr. Arkanjelo WANI LEMI, Presiding Bishop of African Inland Church (AIC) – Juba. 6. Fr. James OYET LATANSIO, General Secretary – South Sudan Council of Churches (SSCC). 7. Mama Elizabeth NYUYUK, for Presbyterian Church of South Sudan/ Sudan (PCSS/S) – Juba. 8. Rev James PAR TAP THON (Moderator Presbyterian Evangelical Church of South Sudan/ Sudan (PECoSS/S). 9. Bishop Nicholas OLING, Christian Brotherhood Church (CBC) – Juba. 10. Rev. Patrick JOK, Sudan Reform Church (SRC) – Juba. 11. Rev. Yaa TAJIR JIBARA, Sudan Interior Church (SIC) – Juba. 12. Mama Agnes Wasuk Sarafino – SSCC National Women Coordinator. Muslim: 13. Mufti. Hamidin Shakerien Al-Awiely. 14. Sheikh Jamaa. Government: 15. H.E. 1st Lt. Gen. Salva Kiir Mayardit, the President of the Republic of South Sudan. 16. Rt. Hon. Antony LINO MAKANA, Speaker of the Transitional National Legislative Assembly (South Sudan – Juba). -

Anglican Cycle of Prayer 2016

Anglican Cycle of Prayer Friday 01-Jan-2016 Psalm: 96: 1,11-end Phil. 4: 10-23 Aba - (Niger Delta, Nigeria) The Most Revd Ugochukwu Ezuoke Saturday 02-Jan-2016 Psalm: 97: 1,8-end Isa. 42: 10-25 Aba Ngwa North - (Niger Delta, Nigeria) The Rt Revd Nathan Kanu Sunday 03-Jan-2016 Psalm: 100 Isa. 43: 1-7 PRAY for The Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand & Polynesia The Most Revd William Brown Turei Pihopa o Aotearora and Primate and Archbishop of the Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand & Polynesia Monday 04-Jan-2016 Psalm: 149: 1-5 Titus 2: 11-14, 3: 3-7 Abakaliki - (Enugu, Nigeria) The Rt Revd Monday Nkwoagu Tuesday 05-Jan-2016 Psalm: 9:1-11 Isa 62:6-12 Aberdeen & Orkney - (Scotland) The Rt Revd Robert Gillies Wednesday 06-Jan-2016 Epiphany Psalm: 72: 1-8 I Tim 1:1-11 O God, who revealed your only Son to the Gentiles by the leading of a star, mercifully grant theat we, who know you now by faith, may after this life enjoy the splendour of your gracious Godhead, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen Thursday 07-Jan-2016 Psalm: 72: 1,10-14 I Tim 1: 12-20 The Most Revd Nicholas Okoh Metropolitan & Primate of all Nigeria & Bishop of Abuja Friday 08-Jan-2016 Psalm: 72: 1,15-end I Tim 2: 1-7 Aguata - (Niger, Nigeria) The Most Revd Christian Efobi Saturday 09-Jan-2016 Psalm: 98 I Tim 2: 8-15 Accra - (Ghana, West Africa) The Rt Revd Daniel Sylvanus Mensah Torto Sunday 10-Jan-2016 Epiphany 1 Psalm: 111: 1-6 I Tim. -

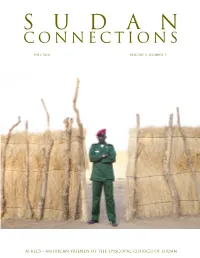

Sudan Connections Exec

S u d A n C o n n ec t i o n S FALL 2010 VOLUME 5, NUMBER 2 AFRECS - AmERiCAn FRiEndS oF thE EpiSCopAl ChuRCh oF SudAn S u d A n C o n n ec t i o n S CONNECTING HOPES AND GIFTS FALL 2010 VOLUME 5, NUMBER 2 American Friends of the Episcopal Church of Sudan (AFRECS) is an organization of CONTENTS U.S. churches, non-governmental organiza- A message from the President ................................................... 3 tions, and individuals who care deeply about David C. Jones the struggles of the Sudanese people. From the Executive Director ..................................................... 4 C. Richard Parkins AFRECS BOARD OF Ecumenical Delegation Sends Urgent Messsage DIRECTORS to UN and US Government ..................................................... 5 Gwinneth Clarkson, Treas. “A Season of Prayer for Sudan” ................................................ 6 Philip H. Darrow, V.P. Is Sudan the South Africa of the 21st Century ......................... 8 Connie Fegley, Sec. Petero Sabune Frederick E. Gilbert The Episcopal Church of Sudan Appeals to the Judith L. Gregory Church in Africa at CAPA in Entebbe ..................................... 9 Ellen J. Hanckel Archbishops Appeal to Government, International Frederick L. Houghton Community as Referendum Approaches .................................. 10 David C. Jones, Pres. Remember to Pray. Teach. Partner. Urge. Give. ...................... 11 E. Ross Kane EPPN Policy Alert ................................................................... 12 Margaret S. Larom With Heart Set on Returning to Sudan, Carolyn Weaver Mackay Work Continues at Home ....................................................... 12 Russell V. Randle Judith Gregory Debra M. Smith “Sudan Will Not Be the Same Again” ..................................... 14 Stacy Carlson Partnerships...Connecting with Our Sudanese Friends ............. 15 Jennifer Ernst EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Missioner from the Diocese of Virginia Serves the ECS ........... -

Francis Meets with the Principal Christian Religious Leaders of South Sudan

N. 161027c Thursday 27.10.2016 Francis meets with the principal Christian religious leaders of South Sudan Today in the Vatican Apostolic Palace the Holy Father Francis received in audience the principal Christian religious leaders of South Sudan: Archbishop Paulino Lukudu Loro of Juba, Rev. Daniel Deng Bul Yak, Archbishop of the Province of the Episcopal Church of South Sudan & Sudan, and Rev. Peter Gai Lual Marrow, Moderator of the Presbyterian Church of South Sudan. In the context of the tensions that divide the population to the detriment of coexistence in the country, during the meeting with the Holy Father it was acknowledged that good and fruitful collaboration exists among the Christian Churches, who wish primarily to offer their contribution to promoting the common good, protecting the dignity of the person, protecting the helpless and implementing initiatives for dialogue and reconciliation. In the light of the Year of Mercy in progress in the Catholic Church, it was underlined that the fundamental experience of forgiveness and acceptance of the other is the privileged path to building peace and to human and social development. In this regard, it was confirmed that the various Christian Churches are committed, in a spirit of communion and unity, to service to the population, promoting the spread of a culture of encounter and sharing. Finally, all parties reiterated their willingness to journey together and to work with renewed hope and mutual trust, in the conviction that, drawing from the positive values inherent in their respective religious traditions, they may show the way to respond effectively to the deepest aspirations of the population, which keenly thirsts for a secure life and a better future.. -

The Distinctive Role of the Catholic Church in Development and Humanitarian Response

The distinctive role of the Catholic Church in development and humanitarian response 7ways the Church makes a difference February 2021 Written by Graham Gordon Additional research by Jerome Foster, Ellen Martin and Francis Stewart Edited by Seren Boyd Acknowledgements Many thanks to all staff and partners who provided examples and other information: Kayode Akintola, Nana Anto-Awuakye, Bernard Balibuno, Ulrike Beck, Winston Berrios, Gabriele Bertani, John Birchenough, John Bosco, Dadirai Chikwengo, Yadviga Clarke, Fergus Conmee, Barbara Davies, Tom Delamere, Clare Dixon, Aisha Dodwell, Hombeline Dulière, Yael Eshel, Nikki Evans, Montserrat Fernández, Eddie Flory, Gisele Henriques, Cecilia Ilorio, Lucy Jardine, Verity Johnson, Linda Jones, Agnes Kalekye, John Kalusa, Kezia Lavan, Moise Liboto, Mary Lucas, Howard Mollett, Conor Molloy, Mwila Mulumbi, Emily Mulville, Ibrahim Njuguna, Catherine Ogolla, Solomon Phirry, Julian Pinzón, Sonia Prichard, Paul Rubangakene, Nelly Shonko, Richard Sloman, Janet Symes and Neil Thorns Cover photo: Sister Yvonne Mwalula carrying gourds as part of the Households in Distress (HID) programme in Zambia (Source: Ben White) The distinctive role of the Catholic Church in development and humanitarian response 3 n Contents Executive summary 4 Introduction and purpose of this paper 11 Section 1. The role of the Church in development 13 Section 2. Seven ways the Church makes a difference in development and humanitarian work 17 1. Rapid, local and inclusive humanitarian response 18 a. Spotlight on the coronavirus response 18 b. Responding to conflict, migration, natural disasters, and food shortages 22 2. Influencing social norms and behaviour 26 3. Peacebuilding, mediation and reconciliation 29 4. Strengthening democratic governance through citizen participation 34 5. -

ECSSSUP Newsletter Apr 21

New relationships for ECSSSUP & TEU ECSSSUP's April 2021 Newsletter The Episcopal University of South Sudan University Partnership March and April have all been about building new relationships, with new trustees and advisors joining ECSSSUP and a new engineering partnership for TEU. Keep reading to find out more - and as ever, we appreciate your interest and commitment to the development of higher education for peace and prosperity in South Sudan. Got questions, comments, ideas? Please do get in touch. Visit Contact us | ecsssup Partnership agreed with local engineering firm As many of you know, the community of Rokon gifted The Episcopal University a substantial amount of land, on which we will develop the administrative centre and a new campus. Rokon was at the centre of much of the conflict, so it is especially exciting to work with them to develop a university that aims to bring peace to the country. Rev Dr Joseph Bilal and the core TEU programme team in Juba recently completed a competitive RFP process to agree a partnership with an engineering firm who will conduct the required surveys. They selected TEFCO, a local firm with international connections and a solid reputation and track record. Work will begin immediately and will take 20 days. Work with TEFCO will enable TEU to continue making progress with Engineering Ministries International (EMI), our partners who will complete the land assessment and produce a concept design for construction in Rokon. This is exciting progress and we look forward to sharing ongoing updates with you! Alex spent the first ten years of his career in behavioural science research in Least Developed Communities, particularly in East Africa, the Middle East and Afghanistan. -

The Church and Strategic Peacebuilding in South Sudan

“One Nation from Every Tribe, Tongue, and People”: The Church and Strategic Peacebuilding in South Sudan John Ashworth and Maura Ryan Introduction When South Sudan celebrated independence on July 9, 2011, Ken Hackett, then CEO of Catholic Relief Services (CRS), was invited to join the United States delegation. That CRS was the only non-governmental organization represented was a testament to CRS’s longstanding com- mitment to humanitarian aid, development, and peacebuilding in South Sudan. But even more, Hackett’s presence recognized the fidelity of the church—a broadly ecumenical Christian church—in the libera- tion struggle of the people of South Sudan. During 22 years of civil war in South Sudan, the church was the only institution that remained on the ground with the people. There was no functioning government, no civil society, no United Nations, no secular NGOs, and even the author- ity of the local chiefs was eroded by the young “comrades” with guns. But wherever there were people, the church was there, providing many of the services that one would normally expect from a government: health care, education, emergency relief, food, shelter, and even secu- rity and protection. People of all religions looked to the church for leadership.1 The church therefore gained a remarkable degree of cred- ibility and moral authority, which places it in a unique position in the John Ashworth is peace, justice and advocacy advisor to various churches and agencies in Sudan and South Sudan, including the Sudan Catholic Bishops’ Conference, Sudan Council of Churches, Catholic Relief Services and Pax Christi. Maura Ryan is John Cardinal O’Hara Associate Professor of Christian Ethics and Associate Dean for the Humanities and Faculty Affairs at the University of Notre Dame.