Theros: Godsend, Part I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MTG-Pl Documentation Release 0.10.1B

MTG-pl Documentation Release 0.10.1b Dominik Kozaczko & strefa-gry.pl Nov 12, 2018 Contents 1 Instrukcje 1 2 Tłumaczenie dodatków 3 2.1 Standard...............................................3 2.2 Modern................................................3 2.3 Pozostałe...............................................4 2.4 Specjalne karty............................................4 3 Warto przeczytac´ 5 4 Ostatnie zmiany 7 5 Ekipa 9 5.1 Origins................................................9 5.2 Battle for Zendikar.......................................... 25 5.3 Dragons of Tarkir........................................... 41 5.4 Uzasadnienie tłumaczen´....................................... 57 5.5 Innistrad............................................... 58 5.6 Dark Ascension........................................... 73 5.7 Avacyn Restored........................................... 83 5.8 Magic the Gathering - Basic Rulebook............................... 95 5.9 Return to Ravnica.......................................... 122 5.10 Gatecrash............................................... 136 5.11 Dragon’s Maze............................................ 150 5.12 Magic 2014 Core Set......................................... 159 5.13 Theros................................................ 171 5.14 Heroes of Theros........................................... 185 5.15 Face the Hydra!........................................... 187 5.16 Commander 2013.......................................... 188 5.17 Battle the Horde!.......................................... -

Barbarian Subclass and Theros Quest Foreword on the World Presented in Mythic Odysseys by Christopher M

Contents Foreword.............................................................................. 1 Barbarian ............................................................................2 Path of the Forestmaster ...............................................2 Quest for the Forestmaster .........................................4 Adventure Prompts .........................................................4 Mountain Crossing ..........................................................5 Traxian Forest ....................................................................5 Forest Overview .............................................................5 Unique Creatures ..........................................................5 Traxian Forest Encounter Tables ...........................6 New Monster Stat Blocks ...........................................11 Sidebars Forestmaster Barbarians and Devotion 4................. Path of the Forestmaster Barbarian subclass and Theros Quest Foreword On the world presented in Mythic Odysseys By Christopher M. Cevasco of Theros, barbarians who follow the Path of the Forestmaster do so only after tracking down a Art Credits mythic being that dwells in the unexplored, ON THE COVER: The Cyclops (1914) by French Symbolist primeval forest beyond Theros's Oraniad painter Odilon Redon (1840 - 1916). Mountains. An overgrown, gentle cyclops touched by the magic of Nyx, the Forestmaster Border pattern around sidebar box adapted from a design becomes a devastating force of destruction by Gordon Johnson from Pixabay. when -

Sprague Ted in North East

Sprague Ted in North East 2 Freeport Rd, North East, PA 16428 Cross Streets: Near the intersection of Freeport Rd and Freeport Ln (814) 725-2319 We found Ted Sprague in 17 states. See Ted's 1) contact info 2) public records 3) Twitter & social profiles 4) background check. Search free at BeenVerified. Seen As: Ted Sprague IV. Addresses: 11078 Freeport Ln, North East, PA. View Profile. Ted G Sprague. As a child growing up in North Korea, Hyeonseo Lee thought her country was "the best on the planet." It wasn't until the famine of the 90s that she began to wonder. She escaped the country at 14, to begin a life in hiding, as a refugee in China. Hers is a harrowing, personal tale of survival and hope â” and a powerful reminder of those who face constant danger, even when the border is far behind. Ted Sprague was a resident of Los Angeles, CA. He was the son of Mindy Sprague and the husband of Karen Sprague. He was an evolved human who had the ability to emit radiation from his body. He was killed by Sylar. Matt and Audrey are investigating the murder of Robert Fresco, an oncologist at UCLA. His body was found burned to a char and emitting 1,800 curies of radiation. A fingerprint found seared into the man's bone is matched using the FBI's CODIS system to Theodore Sprague. Ted Sprague has the ability of radiation. He was mistaken as Sylar a several times. He previously teamed-up with Matt Parkman and Wireless in order to bring down the Company. -

Thursday, July 7, 2016 Email: [email protected] Vol

4040 yearsyears ofof coveringcovering SouthSouth BeltBelt Voice of Community-Minded People since 1976 Thursday, July 7, 2016 Email: [email protected] www.southbeltleader.com Vol. 41, No. 23 Vacation photos sought The Leader is seeking readers’ 2016 vaca- Hughes Road construction causes headaches tion photos for possible publication. A first- and second-place prize of Schlitterbahn tickets Construction work along Hughes Road con- least one shop owner has temporarily shuttered tomobile accidents at the corner of Beamer and vide key upgrades such as water lines, sanitary will be awarded monthly during June, July and tinues to irk local residents and business owners, his doors until the traffi c situation improves. Hughes. While the offi cial number of collisions sewers, new concrete pavement, sidewalks and August to the best submissions. Each month’s who say the project is causing widespread confu- The Leader has put a request in to the City of was unavailable at press time Wednesday, the curbs, street lighting, traffi c control and new sig- first-place winner will be awarded eight tick- sion and traffi c congestion. Houston Public Works and Engineering Depart- Leader has heard from multiple Houston police nage. ets, while each month’s second-place winner A primary concern is the added traffi c when ment to see if the signals can be adjusted at the offi cers that at least one crash takes place per day Despite all of the current issues, construction will be awarded six. traveling north on Beamer toward Hughes from intersection to improve traffi c fl ow. According to at the intersection – some of which are serious in is reportedly on schedule and set to be complete All submissions should include where and Scarsdale. -

Plane Shift: Dominaria

Contents The Domains Seven Pillars of Benalia Church of Serra Tolarian Academies Merfolk of Vodalia Belzenlok’s Cabal Warhosts of Keld Elves of Llanowar PLANE SHIFT: DOMINARIA ©2018 Wizards of the Coast LLC. Magic: The Gathering, Wizards of the Coast, Dungeons & Dragons, their respec- tive logos, Magic, Dominaria, D&D, Player’s Handbook, Dungeon Master’s Guide, Monster Manual, and characters’ distinctive likenesses are property of Wizards of the Coast LLC in the USA and other countries. All rights reserved. www.MagicTheGathering.com Written by James Wyatt with Ashlie Hope Cover art by Tyler Jacobson Editing by Scott Fitzgerald Gray The stories, characters, and incidents mentioned in this publication are entirely fictional. This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of Wizards of the Coast LLC. First Printing: July 2018 Contact Us at Wizards.com/CustomerService Wizards of the Coast LLC PO Box 707 Renton, WA 98057-0707 USA USA & Canada: (800) 324-6496 or (425) 204-8069 Europe: +32(0) 70 233 277 Tolarian Scholar Sara Winters Introduction By the time you read this, you’ll have heard news of the forth- coming publication of Guildmaster’s Guide to Ravnica, which I privately refer to as “Plane Shift: Ravnica.” That book is the primary reason that this installment of the Plane Shift series is relatively late, because the D&D part of my brain was occu- pied with working on it. But that book is also the culmination of all the work I’ve done on this series over the last couple of years. -

Homeland Emergency Response Operational and Equipment Systems

Disclaimer: This report was prepared by the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) under contract with NIOSH. It should not be considered a statement of NIOSH policy or of any agency or individual who was involved. PROJECT HEROES Homeland Emergency Response Operational and Equipment Systems Task 1: A Review of Modern Fire Service Hazards and Protection Needs Presented to: National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Post Office Box 18070 626 Cochrans Mill Road Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15236 Presented by: Occupational Health and Safety Division International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) 1750 New York Avenue, N.W. Washington, DC 20006 13 October 2003 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The first task of Project HEROES was undertaken by the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) to examine and define the protection needs of fire fighters and other first responders during a broad array of different missions. This task began with a review for how the fire service and its responsibilities have changed over the past 20 years since personal protective equipment (PPE) was then affected by Project FIRES. In that 20 year period, the fire service has evolved to gain responsibility for a larger number of missions. Fire suppression is no longer the chief responsibility for most fire departments, but rather responses to a wide range of missions, including emergency medical aid, technical rescue, and more recently the prospect for terrorism events involving weapons of mass destruction. As America’s fire fighters attempt to keep up with these changing roles, it is noted that the level of preparedness and PPE needed to safety carry out the different missions is often lacking. -

D&D Player's Basic Rules V0.2

Player’s Basic Rules Version 0.2 Credits D&D Lead Designers: Mike Mearls, Jeremy Crawford Based on the original D&D game created by E. Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, with Brian Blume, Rob Design Team: Christopher Perkins, James Wyatt, Rodney Kuntz, James Ward, and Don Kaye Thompson, Robert J. Schwalb, Peter Lee, Steve Townshend, Drawing from further development by Bruce R. Cordell J. Eric Holmes, Tom Moldvay, Frank Mentzer, Aaron Allston, Editing Team: Chris Sims, Michele Carter, Scott Fitzgerald Gray Harold Johnson, David “Zeb” Cook, Ed Greenwood, Keith Producer: Greg Bilsland Baker, Tracy Hickman, Margaret Weis, Douglas Niles, Jeff Grubb, Jonathan Tweet, Monte Cook, Skip Williams, Richard Art Directors: Kate Irwin, Dan Gelon, Jon Schindehette, Mari Baker, Peter Adkison, Bill Slavicsek, Andy Collins, and Rob Kolkowsky, Melissa Rapier, Shauna Narciso Heinsoo Graphic Designers: Bree Heiss, Emi Tanji Interior Illustrator: Jaime Jones Playtesting provided by over 175,000 fans of D&D. Thank you! Additional Contributors: Kim Mohan, Matt Sernett, Chris Dupuis, Tom LaPille, Richard Baker, Chris Tulach, Miranda Additional consultation provided by Horner, Jennifer Clarke Wilkes, Steve Winter, Nina Hess Jeff Grubb, Kenneth Hite, Kevin Kulp, Robin Laws, S. John Ross, the RPGPundit, Vincent Venturella, and Zak S. Project Management: Neil Shinkle, Kim Graham, John Hay Production Services: Cynda Callaway, Brian Dumas, Jefferson Dunlap, Anita Williams Brand and Marketing: Nathan Stewart, Liz Schuh, Chris Lindsay, Shelly Mazzanoble, Hilary Ross, Laura Tommervik, Kim Lundstrom Release: August 12, 2014 DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, Wizards of the Coast, Forgotten Realms, the dragon ampersand, Player’s Handbook, Monster Manual, Dungeon Master’s Guide, all other Wizards of the Coast product names, and their respective logos are trademarks of Wizards of the Coast in the USA and other countries. -

HEROES and HOPE 2021 KWAME SIMMONS Founder the Simmons Advantage

HEROES AND HOPE 2021 KWAME SIMMONS Founder The Simmons Advantage A 2015 BET Honors Award recipient and an invited guest to the White House during the Obama administration, Kwame Simmons is a change agent for inner-city schools. With a twenty-year stellar career in education, he has worked tirelessly for students in the nation’s capital and the St. Louis school system. Now, Simmons has brought his knowledge to his hometown to assist with improving the Detroit schools as a consultant. Simmons uses untapped data on how minority students learn to help them succeed in revolutionary ways. “What I’ve tried to do is provide schools with the tools they need to succeed, offering new perspectives to identify their specific challenges.” This year Simmons plans to equip special education students with tools to gain tech jobs and introduce students to coding and gaming as viable career options. JANUARY 2021 SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY NEW YEAR’S DAY MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. DAY INTERNATIONAL DAY OF EDUCATION TRESA GALLOWAY CEO Love Laces As an educator and mother, Tresa Galloway has seen first-hand what happens when children are labeled as having ‘special needs’. When her son was bullied, Galloway prayed for the tools to allow him to handle the bully on his own. That’s when Love Laces was born. Love Laces is a shoelace brand that prints positive affirmations on colorful laces for victims of bullying and low self-esteem. Once labeled as too emotional, Galloway has channeled those emotions to help others. She says, “When you’re faced with fear, you have to come up with strategies on overcoming those fears.” Thanks to her, when a child looks down, they have a reason to look up and know they are loved. -

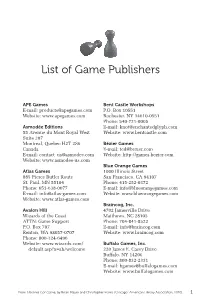

List of Game Publishers

List of Game Publishers APE Games Bent Castle Workshops E-mail: [email protected] P.O. Box 10551 Website: www.apegames.com Rochester, NY 14610-0551 Phone: 540-731-0005 Asmodée Editions E-mail: [email protected] 55 Avenue du Mont Royal West Website: www.bentcastle.com Suite 207 Montreal, Quebec H2T 2S6 Bézier Games Canada E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://games.bezier.com Website: www.asmodee-us.com Blue Orange Games Atlas Games 1000 Illinois Street 885 Pierce Butler Route San Francisco, CA 94107 St. Paul, MN 55104 Phone: 415-252-0372 Phone: 651-638-0077 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.blueorangegames.com Website: www.atlas-games.com Braincog, Inc. Avalon Hill 4702 Jamesville Drive Wizards of the Coast Matthews, NC 28105 ATTN: Game Support Phone: 704-841-8522 P.O. Box 707 E-mail: [email protected] Renton, WA 98057-0707 Website: www.braincog.com Phone: 800-324-6496 Website: www.wizards.com/ Buff alo Games, Inc. default.asp?x=ah/welcome 220 James E. Casey Drive Buffalo, NY 14206 Phone: 800-832-2331 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.buffalogames.com From Libraries Got Game, by Brian Mayer and Christopher Harris (Chicago: American Library Association, 2010). 1 Days of Wonder Gen42 Games 334 State Street Website: www.genfourtwo.com Suite 203 Los Altos, CA 94022 GMT Games Website: www.daysofwonder.com/ P.O. Box 1308 en/ Hanford, CA 93232 Phone: 800-523-6111 Devir US LLC E-mail: [email protected] 309 S. -

Planeswalkers of Ravnica by Christopher Willett

PLANESWALKERS OF RAVNICA BY CHRISTOPHER WILLETT Table of Contents Foreword ...................................................................................................................................................... 2 Planeswalker ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Color Based Alignment ................................................................................................................................. 4 White ................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Blue .................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Black .................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Red .................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Green ................................................................................................................................................................................ 8 Colors of Magic ......................................................................................................................................... -

COVID-19 & Healthcare Workers: Heroes Or Villains?

COVID-19 & Healthcare Workers: Heroes or Villains? By Elizabeth Ziemba, JD, MPH, President, Medical Tourism Training Part 2 of 3-part series exploring the relationship between and among healthcare workers, society, patients, and the impact of COVID-19 on the delivery of healthcare services. The COVID-19 pandemic has placed unprecedented pressures on healthcare systems and healthcare professionals. Societies have responded in conflicting and contradictory ways resulting in healthcare workers to become the targets of a range of emotion from adulation to hatred. What impact have these responses had on healthcare professionals and the organizations for which they work? Healthcare Professionals as Heroes People around the world are expressing their appreciation to healthcare professionals for the work that they are doing. Social media pages for hospitals and clinics are filled with messages of gratitude, examples of courage, wonderful stories, and other positive sentiments. Hospitals and clinics are inviting these messages and have created programs to celebrate Healthcare Heroes. Websites have sprung up celebrating “our heroes”.i Few people are asking doctors, nurses, and other Gardiner Anderson/for New York Daily News healthcare professionals how they think and feel about being called “heroes”. Formal research seems to have left this question unexamined; however, there are interesting responses from healthcare professionals themselves. Social media, marketing & branding Everyone likes to be thanked for doing a good job. Humans appreciate being acknowledged and praised for their contributions. Many people simply derive their own satisfaction from a job well done. Healthcare professionals, in particular, are drawn to their work because they want to help people. -

AND the IMPLICIT LEARNING of ENGLISH Florianópolis 2018

i Raimundo Nonato de Sousa Filho TASK-GAME: ‘MAGIC THE GATHERING’ AND THE IMPLICIT LEARNING OF ENGLISH Dissertação submetida ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Inglês: Estudos Linguísticos e Literários da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina para a obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Letras. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Raquel Souza Ferraz D’Ely Florianópolis 2018 ii Ficha de identificação da obra elaborada pelo autor através do Programa de Geração Automática da Biblioteca Universitária da UFSC. iii iv v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS On a weekend night, about 16 years ago, I walked around UFSC with some friends. I looked at the buildings, and I could see some shadows of students and sometimes their heads through the windows. I thought to myself: “This is a place I will never be able to reach”. Back then, I had to work 44 hours a week to help my family. Before that, I had studied my entire life in a public school where sometimes I was sent home after lunch or the snack break because teachers used to be absent. Things have changed, however, and I had the opportunity to leave my job and go back to studying. In March of 2008, I was having my first class at UFSC. I was living a dream. Four years later, I proved to myself that I could go all the way through by graduating college. I was thrilled! After graduating college, I thought that it was the furthest I could go. I was wrong again. I just needed some time to take it all in. Four years later, I was a master’s student.