Hybrid Clubs?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Portfolio Document

games assets portfolio FULL GAME CREDITS ACTIVISION InXILE Starbreeze Call of Duty: Ghosts Heist The walking dead Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare Call of Duty: Black Ops 3 IO INTERACTIVE SQUARE ENIX Call of Duty: Infinity Warfare Hitman: Absolution Bravely Default BIOWARE KABAM THQ Dragon Age: Inquisition Spirit Lords Darksiders Saints Row 2 CRYSTAL DYNAMICS KONAMI Tomb Raider 2013 Silent Hill: Shattered Memories TORUS Rise of the Tomb Raider Barbie: Life in the Dreamhouse MIDWAY Falling Skies: Planetary Warfare ELECTRONIC ARTS NFL Blitz 2 How to Train Your Dragon 2 DarkSpore Penguins of Madagascar FIFA 09/10/11/12/13/14/15/16/17/18/19 PANDEMIC STUDIOS Fight Night 4 The Sabateur VICIOUS CYCLE Harry Potter – Deathly Hallows Part 1 & 2 Ben 10: Alien Force NBA Live 09/10/12/13 ROCKSTAR GAMES Dead Head Fred NCAA Football 09/10/11/12/13/14 LA Noire NFL Madden 11/12/13/14/15 / 18 Max Payne 2 2K NHL 09/10/11/12/13/16/17/18 Max Payne 3 NBA 2K14/15 Rory Mcilroy PGA Tour Red Dead Redemption Tiger Woods 11/12/13 Grand Theft Auto V 505 GAMES Warhammer Online: Age of Reckoning Takedown (Trailer) UFC 1/ 2 /3 SONY COMPUTER ENTERTAINMENT NFS – Payback God of War 2 EPIC GAMES Battlefield 1 In the name of Tsar Sorcery Gears of War 2 Killzone: Shadow Fall UBISOFT Assassin’s Creed GAMELOFT Starlink Asphalt 9 Steep Rainbow 6 KEYFRAME ANIMATION ASSET CREATION MOCAP CLEANUP LIGHTING FX UBISOFT Assassin Creed Odyssey UBISOFT UBISOFT Assassin Creed Odyssey UBISOFT Assassin Creed Odyssey UBISOFT Assassin Creed Odyssey UBISOFT Assassin Creed Odyssey Electronic Arts -

United States Securities and Exchange Commission Form

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 OR 15(d) of The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported) February 6, 2019 TAKE-TWO INTERACTIVE SOFTWARE, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 001-34003 51-0350842 (State or other jurisdiction (Commission (IRS Employer of incorporation) File Number) Identification No.) 110 West 44th Street, New York, New York 10036 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code (646) 536-2842 (Former name or former address, if changed since last report.) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions (see General Instruction A.2. below): o Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) o Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) o Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) o Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is an emerging growth company as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933 (§230.405 of this chapter) or Rule 12b-2 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (§240.12b-2 of this chapter). Emerging growth company o If an emerging growth company, indicate by check mark if the registrant has elected not to use the extended transition period for complying with any new or revised financial accounting standards provided pursuant to Section 13(a) of the Exchange Act. -

How to Install Star Control

X14 SR Manual 5/6/96 1:44 PM Page 1 STAR CONTROL 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Credits 5 How to install Star Control 6 System Requirements 6 Installation for a Hard Drive System 6 Starting the Game 7 Configuration: Setting Graphics, Sound, and Other Options 7 Player Controls 9 Menus 9 Keyboard Ship Controls 10 Joystick Ship Controls 10 Other Special Controls 10 Earth’s Treaty of Alliance with the Free Stars 10 Article One 11 Article Two 11 Article Three 11 Special Clauses 11 Playing the Game 12 The Main Activity Menu 12 Setting Player Options 12 Control Options 13 Using Options 13 Bulletin from ComSim Central 13 Practice 14 Flying Ships in Combat 14 Melee 16 Full Game 31 Selecting a Scenario 31 Loading a Saved Game 31 Fleet Command View 31 The Rotating Starfield 33 Going to Combat 35 X14 SR Manual 5/6/96 1:44 PM Page 2 STAR CONTROL 2 Precursor Relics 37 Strategic Ship Powers 38 Winning the Game 38 Saving a Game in Progress 39 Appendix One: Scenario Descriptions 39 Appendix Two: Utilities 40 Keyboard Configuration Utility 40 Scenario Editor 41 Author Biographies 45 Troubleshooting Guide 46 Legal Mumbo Jumbo 49 X14 SR Manual 5/6/96 1:44 PM Page 3 STAR CONTROL 3 Introduction... CONTACT WITH ALIEN BEINGS REPORTED! Rumor of Stellar Threat Confirmed. TheInternational Press-Dispatch, March 12, 2612. By Le-Quo Garibaldi, Press-Dispatch Interstellar Correspondent. Rumors of a hostile stellar threat th toe earth and its surroundigs were confirmed yesterday in an extraordinary meeting between a Star Control scout ship and a Chenjesu vessel near the Ceres base. -

Case 1:16-Cv-00454-RGA Document 1 Filed 06/17/16 Page 1 of 39 Pageid #: 1

Case 1:16-cv-00454-RGA Document 1 Filed 06/17/16 Page 1 of 39 PageID #: 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE ACCELERATION BAY LLC, a Delaware ) Limited Liability Corporation, ) ) C.A. No. Plaintiff, ) ) DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL v. ) ) ELECTRONIC ARTS INC., ) a Delaware Corporation, ) ) Defendant. ) COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT Case 1:16-cv-00454-RGA Document 1 Filed 06/17/16 Page 2 of 39 PageID #: 2 COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT Plaintiff Acceleration Bay LLC (“Acceleration Bay”) files this Complaint for Patent Infringement and Jury Demand against Defendant Electronic Arts Inc. (“Defendant” or “EA”) and alleges as follows: BACKGROUND This Complaint alleges Defendant infringed and continues to infringe the same Acceleration Bay Patents (defined below) at issue in Acceleration Bay LLC v. Take-Two Interactive Software Inc., 1:15-cv-00282-RGA (D. Del.), filed on March 30, 2015. The Acceleration Bay Patents asserted here and in the previous case were assigned by the Boeing Company to Acceleration Bay. On June 3, 2016, the District Court issued an Order in the previous case finding that Acceleration Bay lacked prudential standing. 1:15-cv-00282-RGA, D.I. 143. Subsequent to that Order, Acceleration Bay and the Boeing Company entered into an Amended and Restated Patent Purchase Agreement resolving all of the issues identified by the District Court in its June 3, 2016 Order. THE PARTIES Acceleration Bay is a Delaware limited liability corporation, with its principal place of business at 370 Bridge Parkway, Redwood City, California 94065. Acceleration Bay is an incubator for next generation businesses, in particular companies that focus on delivering information and content in real-time. -

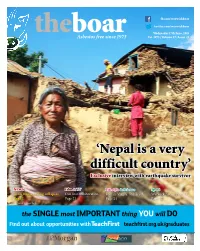

'Nepal Is a Very Difficult Country'

fb.com/warwickboar twitter.com/warwickboar Wednesday 17th June, 2015 theboar Est. 1973 | Volume 37 | Issue 12 Asbestos free since 1973 ‘Nepal is a very difficult country’ Exclusive interview with earthquake survivor NEWS Film & TV Lifestyle & Science Sport Avon House ceiling collapses Our first collaboration Female Viagra: The Truth Warwick Archery on TV Page 2 Page 21 Page 24 Page 32 » Photo: Varun Kumar Todi the single most important thing you will do Find out about opportunities with teachfirst.org.uk/graduates TF2897 The BoarSponsored Warwick 265x44 by: Banner.indd 1 18/12/2013 16:37 theboar.org/News | @BoarNews | NEWS 2 2 News theboar.org Connor O’Shea years, according to the statement. Hiran Adhia Our source suggested that there was asbestos in the Avon Studio, Ceiling collapses which may have been exposed due A ceiling has collapsed in West- to the damage. wood’s Avon House studio. The Asbestos is a hazardous sub- lighting rig collapsed overnight stance which was commonly used on April 1, forcing the studio’s clo- in building materials up until the sure the next day. 1990s for insulation and fireproof- A source, who wishes to remain ing. The substance is only harmful without warning anonymous, has shared a picture of if building materials are damaged. the incident which was taken by a If damaged, even small levels of fireman. The image shows the en- exposure can lead lead to respirato- tire lighting rig collapsed on the ry problems, according to the Brit- floor of the studio, causing signif- ish Lung Foundation. icant interior damage. -

PGA TOUR® 2K21 Available Now

Golf Got Game: PGA TOUR® 2K21 Available Now August 21, 2020 Bring the clubhouse to your house and take on 12 PGA TOUR pros in a quest to capture the FedExCup trophy in the ultimate golf sim from 2K and HB Studios NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Aug. 21, 2020-- For seasoned golf pros and rookies alike, your tee time has finally arrived: PGA TOUR® 2K21 is available now for the PlayStation®4 system, the Xbox One family of devices, including the Xbox One X and Windows PC via Steam, Nintendo Switch™ system* and Stadia. Developed byHB Studios, the team behind The Golf Club 2019 Featuring PGA TOUR, PGA TOUR 2K21 is a real-deal golf simulation experience featuring officially licensed PGA TOUR pros, courses, gear and apparel brands. This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20200821005068/en/ PGA TOUR 2K21 is built around the belief that golf is for everyone. Whether you’re a pro who’s no stranger to the dance floor or a weekend warrior looking to try your luck for the first time, there’s something here for you. Rookies can take advantage of real-time tutorials, tips and shot suggestions, while veterans can master their games with advanced features, including Pro Vision, Distance Control, Shot Shaper and Putt Preview. Tee it up solo or hit the links with friends by playing local and online matches, including Alt-Shot, Stroke Play, Skins and 4-Player Scramble. Taking the social experience to the next level, command your Clubhouse with Online Societies, where you can run full seasons and tournaments while earning bragging rights on the course. -

Rory Mcilroy PGA TOUR Manual

WARNING Before playing this game, read the Xbox One™ system, and accessory manuals for important safety and health information. www.xbox.com/support. Important Health Warning: Photosensitive Seizures A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people with no history of seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause “photosensitive epileptic seizures” while watching video games. Symptoms can include light-headedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, momentary loss of awareness, and loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents, watch for or ask children about these symptoms—children and teenagers are more likely to experience these seizures. The risk may be reduced by being farther from the screen; using a smaller screen; playing in a well-lit room, and not playing when drowsy or fatigued. If you or any relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. CONTENTS CONTROLS...............................................3 GAME MODES ........................................10 THE BASICS ............................................5 LIMITED 90-DAY WARRANTY .....12 ON THE COURSE .................................7 NEED HELP? ...........................................13 -

Playstation Games

The Video Game Guy, Booths Corner Farmers Market - Garnet Valley, PA 19060 (302) 897-8115 www.thevideogameguy.com System Game Genre Playstation Games Playstation 007 Racing Racing Playstation 101 Dalmatians II Patch's London Adventure Action & Adventure Playstation 102 Dalmatians Puppies to the Rescue Action & Adventure Playstation 1Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 2Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 3D Baseball Baseball Playstation 3Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 40 Winks Action & Adventure Playstation Ace Combat 2 Action & Adventure Playstation Ace Combat 3 Electrosphere Other Playstation Aces of the Air Other Playstation Action Bass Sports Playstation Action Man Operation EXtreme Action & Adventure Playstation Activision Classics Arcade Playstation Adidas Power Soccer Soccer Playstation Adidas Power Soccer 98 Soccer Playstation Advanced Dungeons and Dragons Iron and Blood RPG Playstation Adventures of Lomax Action & Adventure Playstation Agile Warrior F-111X Action & Adventure Playstation Air Combat Action & Adventure Playstation Air Hockey Sports Playstation Akuji the Heartless Action & Adventure Playstation Aladdin in Nasiras Revenge Action & Adventure Playstation Alexi Lalas International Soccer Soccer Playstation Alien Resurrection Action & Adventure Playstation Alien Trilogy Action & Adventure Playstation Allied General Action & Adventure Playstation All-Star Racing Racing Playstation All-Star Racing 2 Racing Playstation All-Star Slammin D-Ball Sports Playstation Alone In The Dark One Eyed Jack's Revenge Action & Adventure -

Q1 2016 Electronic Arts Inc Earnings Call on July 30, 2015 / 9:00PM

THOMSON REUTERS STREETEVENTS EDITED TRANSCRIPT EA - Q1 2016 Electronic Arts Inc Earnings Call EVENT DATE/TIME: JULY 30, 2015 / 9:00PM GMT OVERVIEW: EA reported 1Q16 non-GAAP net revenue of $693m and non-GAAP diluted EPS of $0.15. Co. expects FY16 GAAP revenue to be $4.3b and GAAP fully-diluted EPS to be $1.98. THOMSON REUTERS STREETEVENTS | www.streetevents.com | Contact Us ©2015 Thomson Reuters. All rights reserved. Republication or redistribution of Thomson Reuters content, including by framing or similar means, is prohibited without the prior written consent of Thomson Reuters. 'Thomson Reuters' and the Thomson Reuters logo are registered trademarks of Thomson Reuters and its affiliated companies. JULY 30, 2015 / 9:00PM, EA - Q1 2016 Electronic Arts Inc Earnings Call CORPORATE PARTICIPANTS Chris Evenden Electronic Arts Inc. - VP IR Andrew Wilson Electronic Arts Inc. - CEO Blake Jorgensen Electronic Arts Inc. - EVP, CFO Peter Moore Electronic Arts Inc. - COO CONFERENCE CALL PARTICIPANTS Chris Merwin Barclays Capital - Analyst Ryan Gee BofA Merrill Lynch - Analyst Colin Sebastian Robert W. Baird & Company, Inc. - Analyst Stephen Ju Credit Suisse - Analyst Brian Pitz Jefferies LLC - Analyst Drew Crum Stifel Nicolaus - Analyst Ben Schachter Macquarie Research - Analyst Mike Hickey The Benchmark Company - Analyst Eric Handler MKM Partners - Analyst Doug Creutz Cowen and Company - Analyst PRESENTATION Operator Welcome and thank you all for standing by. (Operator Instructions). Today's conference is being recorded. If you have any objections, you may disconnect at this time. Now I will turn the meeting over to your host, Mr. Chris Evenden. Sir, you may begin. Chris Evenden - Electronic Arts Inc. -

ELECTRONIC ARTS Q4 FY15 PREPARED COMMENTS May 5, 2015 Chris: Thank You. Welcome to EA's Fiscal 2015 Fourth Quarter Earnings C

ELECTRONIC ARTS Q4 FY15 PREPARED COMMENTS May 5, 2015 Chris: Thank you. Welcome to EA’s fiscal 2015 fourth quarter earnings call. With me on the call today are Andrew Wilson, our CEO, and Blake Jorgensen, our CFO. Frank Gibeau, our EVP of Mobile, and Peter Moore, our COO, will be joining us for the Q&A portion of the call. Please note that our SEC filings and our earnings release are available at ir.ea.com. In addition, we have posted earnings slides to accompany our prepared remarks. After the call, we will post our prepared remarks, an audio replay of this call, and a transcript. A couple of quick notes on our calendar: the date of our next earnings report will be Thursday, July 30. And our E3 press conference is at 1pm Pacific Time on Monday, June 15. This presentation and our comments include forward-looking statements regarding future events and the future financial performance of the Company. Actual events and results may differ materially from our expectations. We refer you to our most recent Form 10-Q for a discussion of risks that could cause actual results to differ materially from those discussed today. Electronic Arts makes these statements as of May 5, 2015 and disclaims any duty to update them. During this call unless otherwise stated, the financial metrics will be presented on a non-GAAP basis. Our earnings release and the earnings slides provide a reconciliation of our GAAP to non-GAAP measures. These non-GAAP measures are not intended to be considered in isolation from, as a substitute for, or superior to our GAAP results. -

Pre-Order Madden Nfl 21

OFFERS VALID UNLESSAUGUST NOTED OTHERWISE 16 22, 2020 AVAILABLE AUGUST 25 PRE-ORDER OFFERS EXPIRE ON AUG 28, 2020 FOR NEW PURCHASES OF MADDEN NFL 21 (“PRODUCT”) AND INCLUDE 1 NFL TEAM ELITE PACK, 5 GOLD TEAM FANTASY PACKS, AND A BASE UNIFORM SET. MVP EDITION PRE-ORDER INCLUDE POWER UP FOR LAMAR JACKSON ELITE ITEM. DELUXE EDITION CONTAINS 7 MUT GOLD TEAM FANTASY PACKS. MVP EDITION CONTAINS 12 MUT GOLD TEAM FANTASY PACKS, 1 LARGE QUICKSELL TRAINING PACK, COMPETITIVE GAMING PACK, MCS ULTIMATE CHAMPION PACK, AND LAMAR JACKSON ELITE ITEM. GOLD TEAM FANTASY PACKS CONTAIN 1 OF 32 GOLD NFL TEAM PACKS WITH AT LEAST 1 GOLD PLAYER FROM THE SELECTED TEAM. ALL ELITE PLAYER AND PACK ITEMS ARE NON-AUCTIONABLE AND NON-TRADABLE. FOR RETAIL PREORDERS, SEE RETAILER FOR EARLY ACCESS DISTRIBUTION DETAILS AND PICK-UP TIME. FOR DIGITAL PRE-ORDERS, PRODUCT WILL BE AVAILABLE TO DOWNLOAD ON AUG 25, 2020. ACCESS TO CONTENT MAY REQUIRE REGISTRATION WITH A SINGLE-USE CODE. CONSULT YOUR RETAILER FOR DISTRIBUTION DETAILS. CODES MUST BE REDEEMED BY SEP 1, 2021 TO RECEIVE PRE-ORDER CONTENT. ALL ITEMS WILL BE ENTITLED UPON LOGGING INTO YOUR EA ACCOUNT AT GAME LAUNCH AND ACCESSING THE MUT IN-GAME STORE. ALL ITEMS WILL BE ENTITLED UPON CODE REDEMPTION, LOGGING INTO YOUR EA ACCOUNT AT GAME LAUNCH, AND ACCESSING THE MUT IN-GAME STORE. VALID WHEREVER PRODUCT IS SOLD. OFFER MAY NOT BE SUBSTITUTED, EXCHANGED, SOLD, OR REDEEMED FOR CASH OR OTHER GOODS OR SERVICES. MAY NOT BE COMBINED WITH ANY OTHER PROMOTIONAL OR DISCOUNT OFFER, UNLESS EXPRESSLY AUTHORIZED BY EA; MAY NOT BE COMBINED WITH ANY PREPAID CARD REDEEMABLE FOR THE APPLICABLE CONTENT. -

Weekly News Digest #11

Mar 15 — Mar 21, 2021 Weekly News Digest #11 ironSource goes pubic via SPAC at $11.1B valuation Israelbased ironSource will go public through the merger with special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) Thoma Bravo Advantage at $11.1B combined postmoney equity value. Posttransaction the company will have around $740m of unrestricted cash on its balance sheet with ironSource shareholders owning approximately 77% of shares in the company. The postmoney enterprise value would be equal to $10.3B. In 2020, ironSource reported $332.9m Revenue (+83% compared to 2019) and $104m adj. EBITDA resulting in 31% margin. The implied valuation multiples are close to global SaaS companies: — based on 2021E: 22.5x EV/Rev’21 and 79.5x EV/adj. EBITDA’21; — based on 2022E: 16.5x EV/Rev’22 and 55.0x EV/adj. EBITDA’22. Business Overview Founded in 2010, ironSource is a software development business specializing in the distribution and monetization of apps with a particular focus on mobile games via its ad network, mobile ad mediation, and UA platforms. ironSource claims to be the #3 independent ads platform for game developers after Google and Facebook. ironSource Sonic solutions are used by 90% of the top20 most downloaded games worldwide. Among its customers and partners are such gaming companies as Activision, Playrix, Square Enix, Big Fish Games, Jam City, and many others — the company reports over 2.3 billion MAU across its global customer base. In Feb 2020, ironSource launched hypercasual game studio Supersonic, which focuses on the development and publishing of addriven games.