J E W I S H I N S P I R a T I O N Spring 201 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Impact 3 Table of Contents

OUR IMPACT 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Taking Care of Needs (Vulnerable Populations & Urgent Needs) ................1 Local Agencies Hebrew Free Loan .....................................2 Jewish Family Service ....................................3 Jewish Senior Life .....................................4 JVS .............................................5 Overseas American Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) .......................6 Federation Community Needs Programs Community-Wide Security .................................7 Real Estate / Community Infrastructure ..........................8 Building A Vibrant Future (Jewish Identity and Community) . 9 Local Agencies BBYO ...........................................10 Jewish Community Center .................................11 Jewish Community Relations Council ...........................12 Tamarack Camps ......................................13 Hillel On Campus Michigan State University Hillel and the Hillel Campus Alliance of Michigan . 14 Hillel of Metro Detroit ...................................15 University of Michigan Hillel ...............................16 Jewish Day Schools Akiva Hebrew Day School .................................17 Jean and Samuel Frankel Jewish Academy .........................17 Hillel Day School .....................................17 Yeshiva Beth Yehudah ...................................17 Yeshiva Gedolah ......................................17 Yeshivas Darchei Torah ..................................17 Overseas Jewish Agency for Israel (JAFI) ...............................18 -

Alabama Arizona Arkansas California

ALABAMA ARKANSAS N. E. Miles Jewish Day School Hebrew Academy of Arkansas 4000 Montclair Road 11905 Fairview Road Birmingham, AL 35213 Little Rock, AR 72212 ARIZONA CALIFORNIA East Valley JCC Day School Abraham Joshua Heschel 908 N Alma School Road Day School Chandler, AZ 85224 17701 Devonshire Street Northridge, CA 91325 Pardes Jewish Day School 3916 East Paradise Lane Adat Ari El Day School Phoenix, AZ 85032 12020 Burbank Blvd. Valley Village, CA 91607 Phoenix Hebrew Academy 515 East Bethany Home Road Bais Chaya Mushka Phoenix, AZ 85012 9051 West Pico Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90035 Shalom Montessori at McCormick Ranch Bais Menachem Yeshiva 7300 N. Via Paseo del Sur Day School Scottsdale, AZ 85258 834 28th Avenue San Francisco, CA 94121 Shearim Torah High School for Girls Bais Yaakov School for Girls 6516 N. Seventh Street, #105 7353 Beverly Blvd. Phoenix, AZ 85014 Los Angeles, CA 90035 Torah Day School of Phoenix Beth Hillel Day School 1118 Glendale Avenue 12326 Riverside Drive Phoenix, AZ 85021 Valley Village, CA 91607 Tucson Hebrew Academy Bnos Devorah High School 3888 East River Road 461 North La Brea Avenue Tucson, AZ 85718 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Yeshiva High School of Arizona Bnos Esther 727 East Glendale Avenue 116 N. LaBrea Avenue Phoenix, AZ 85020 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Participating Schools in the 2013-2014 U.S. Census of Jewish Day Schools Brandeis Hillel Day School Harkham Hillel Hebrew Academy 655 Brotherhood Way 9120 West Olympic Blvd. San Francisco, CA 94132 Beverly Hills, CA 90212 Brawerman Elementary Schools Hebrew Academy of Wilshire Blvd. Temple 14401 Willow Lane 11661 W. -

Jointorah Education Revolution

the JOIN TORAH EDUCATION REVOLUTION Afikei Torah • Ahavas Torah • Ahava V'achva • Aish HaTorah of Cleveland • Aish HaTorah of Denver • Aish HaTorah of Detroit • Aish HaTorah of Jerusalem • Aish HaTorah of Mexico • Aish HaTorah of NY • Aish HaTorah of Philadelphia • Aish HaTorah of St Louis • Aish HaTorah of Thornhill • Ateres Yerushalayim • Atlanta Scholars Kollel • AZ Russian Programs • Bais Yaakov of Boston • Bais Yaakov of LA • Bar Ilan University • Batya Girls / Torah Links • Bay Shore Jewish Center Be'er Miriam • Belmont Synagogue • Beth Din • Beth Jacob • Beth Jacob Congregation • Beth Tfiloh Upper School Library • Bnei Shalom Borehamwood & • Elstree Synagogue • Boston's Jewish Community Day School • Brandywine Hills Minyan • Calabasas Shul • Camp Bnos Agudah • Chabad at the Beaches • Chabad Chabad of Montreal • Chai Center of West Bay • Chaye Congregation Ahavat Israel Chabad Impact of Torah Live Congregation Beth Jacob of Irvine • Congregation Light of Israel Congregation Derech (Ohr Samayach) Organizations that have used Etz Chaim Center for Jewish Studies Hampstead Garden Suburb Synagogue • Torah Live materials Jewish Community Day Jewish FED of Greater Atlanta / Congregation Ariel • Jewish 600 Keneseth Beth King David Linksfield Primary and High schools • King 500 Mabat • Mathilda Marks Kennedy Jewish Primary School • Me’or 400 Menorah Shul • Meor Midreshet Rachel v'Chaya 206 MTA • Naima Neve Yerushalayim • 106 Ohab Zedek • Ohr Pninim Seminary • 77 Rabbi Reisman Yarchei Kalla • Rabbi 46 Shapell's College • St. John's Wood Synagogue • The 14 Tiferes High Machon Shlomo 1 Me’or HaTorah Meor • Me'or Midreshet Rachel v'Chaya College • Naima Neve Yerushalayim • Ohab Zedek • Ohr Pninim Seminary • Rabbi Reisman Yarchei Kalla • Rabbi 2011 2014 2016 2010 2015 2013 2012 2008 2009 Shapell's College St. -

M I C G a N Jewis11 History

M I C G A N JEWIS11 HISTORY II C NIG4 May, 1965 Iyar, 5725 JEWISH HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MICHIGAN JEWISH HISTORY (tc:-1 Intim) nro: Dr= 115V4 1w ... "When your children shall ask their fathers in time to come . Joshua 4:21 Volume 5 May, 1965 — Iya•, 5725 Number 2 The Deveopment of Jewish Education in Detroit — Morris Garrett . Page .1 Federation Presents Archives to Burton Historical Collection Page 11 Book Review of Eugene T. Peterson's "Gentlemen on the Frontier" — Allen A. Warsot Page 13 PUBLICATION COMMITTEE Irving I. Katz, Editor Emanuel Applebaum Larwence A. Rubin Irving I. Edgar Allen A. Warsen Michigan Jewish History is published semi-annually by the Jewish Historical Society of Michigan. Correspondence concerning contributors and books for review may be sent to the editor, 8801 Woodward Avenue, Detroit, Michigan 48202. The Society assumes no responsibility for statements made by contri- butors. 1 — Jewish Historical Society of Michigan 8801 Woodward Avenue Detroit, Michigan 48202 OFFICERS Dr. Irving I. Edgar President Mrs. Ettie Raphael Vice-President Jonathan D. Hyams Treasurer Mrs. Lila Avrin Secretary Allen A. Warsen Honorary President BOARD OF DIRECTORS Rabbi Morris Adler Dr. Leonard W. Moss Rabbi Emanuel Applebaum Miss Sadie Padover Mrs. Irving I. Edgar Bernard Panush Charles E. Feinberg Dr. A. S. Rogoff Rabbi Leon Fram Jay Rosenshine Morris Garvett Gregory A. Ross Irwin T. Holtzman Dr. A .W. Sanders Irving I. Katz Irwin Shaw Louis LaMed Leonard N. Simons Prof. Shlomo Marenoff Allan L. Waller Dr. Charles J. Meyers Dr. Israel Wiener Mrs. Marshall M. Miller PAST PRESIDENTS Allen A. -

All Positions.Xlsx

Job Title Location Employer Job Title Location Employer YU's Jewish Job Fair 2017 Summer Camp Jobs New York , NY 92Y Camps Science (HS) Cleveland, Ohio Fuchs Mizrachi School 3rd and 4th grade Judaics teacher Charleston, SC Addlestone Hebrew Academy Science (Junior HS) Cleveland, Ohio Fuchs Mizrachi School Executive Assistant Hewlett, NY Aleph Beta GS Classroom Teachers Lawrence, NY HAFTR Lower School EC Teacher Monsey, NY ASHAR JS Teacher Lawrence, NY HAFTR Lower School Elem & MS Rebbeim Monsey, NY ASHAR JS/GS AT Lawrence, NY HAFTR Lower School Elem and MS GS teachers Monsey, NY ASHAR MS Math Teacher Lawrence, NY HAFTR Middle School Elem and MS Morot Monsey, NY ASHAR MS Rebbe Lawrence, NY HAFTR Middle School LS (1‐4) JS Teacher Atlanta, GA Atlanta Jewish Academy MS JS Teacher‐ West Hatford, CT Hebrew Academy of Greater Hartford MS (5‐8) JS Atlanta, GA Atlanta Jewish Academy GS MS Woodmere, NY Hebrew Academy of Long Beach ATs for the 17‐18 School Year Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Hebrew Language MS Woodmere, NY Hebrew Academy of Long Beach EC Head Teacher Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Limudei Kodesh MS Woodmere, NY Hebrew Academy of Long Beach EC Hebrew Teacher (Ganenent) Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Tanach Department Head & Teacher Woodmere, NY Hebrew Academy of Long Beach GS Head Teacher, Grades 1‐8 Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Communications W. Hempstead, NY Hebrew Academy of Nassau County JS Teachers Paramus, NJ Ben Porat Yosef Dean of Students Uniondale, NY Hebrew Academy of Nassau County MS Judaics Teacher Silver Spring, MD Berman Hebrew Academy Elem Teachers & ATs W. -

2018 Fellow Bios

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 2018 Fellow Bios Jonathan Arking is a junior at Beth Tfiloh High school. There, he captains the Model UN and cross- country teams and serves as the head of the school's AIPAC (American Israel Public Affairs Committee) club. In addition, he participates in Mock Trial, NHS, Kolenu (the high school choir), and the ultimate Frisbee team. Outside of school, Jonathan frequently reads the Torah portion and leads the services at Congregation Netivot Shalom, the Modern Orthodox synagogue he and his family founded, and now attend. In his free time, Jonathan loves running, reading, and singing -- especially traditional Jewish songs. He is greatly excited to be a Bronfman Fellow and looks forward to an inspiring and insightful summer. Hannah Bashkow is currently a junior at Tandem Friends School. Before that, she attended the Charlottesville Waldorf School through eighth grade. She and her family are members of Charlottesville’s Congregation Beth Israel, where they regularly attend the Saturday morning traditional egalitarian minyan. At the synagogue, she works as a Hebrew tutor and helps kids prepare for their b’nei mitzvah. She is an enthusiastic artist who enjoys working in many media. In past summers, she has attended Nature Camp, a local field ecology camp, and has traveled with her family to Israel, Europe, and Papua New Guinea. Sarah Bock is a junior at Scarsdale High School and a member of Westchester Reform Temple. At SHS, Sarah is a member of Signifer, which functions as Scarsdale’s Honor Society, as well as a peer tutoring program. She is on the school’s cross country and track teams and is a member of the Pratham club, which raises money to fund women’s education in India. -

MST 2018-2019 Year 2 Reimbursement Listing

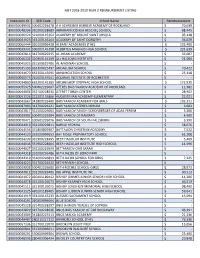

MST 2018-2019 YEAR 2 REIMBURSMENT LISTING Institution ID SED Code School Name Reimbursement 800000039032 500402226478 A H SCHREIBER HEBREW ACADEMY OF ROCKLAND $ 70,039 800000048206 310200228689 ABRAHAM JOSHUA HESCHEL SCHOOL $ 68,445 800000046124 321000145364 ACADEMY OF MOUNT SAINT URSULA $ 95,148 800000041923 353100145263 ACADEMY OF SAINT DOROTHY $ 36,029 800000060444 010100996428 ALBANY ACADEMIES (THE) $ 102,490 800000039341 500101145198 ALBERTUS MAGNUS HIGH SCHOOL $ 231,639 800000042814 342700629235 AL-IHSAN ACADEMY $ 33,087 800000046332 320900145199 ALL HALLOWS INSTITUTE $ 21,084 800000045025 331500629786 AL-MADINAH SCHOOL $ - 800000035193 662300625497 ANDALUSIA SCHOOL $ 70,422 800000034670 662300145095 ANNUNCIATION SCHOOL $ 25,148 800000050573 261600167041 AQUINAS INSTITUTE OF ROCHESTER $ - 800000034860 662200145185 ARCHBISHOP STEPINAC HIGH SCHOOL $ 172,930 800000055925 500402229697 ATERES BAIS YAAKOV ACADEMY OF ROCKLAND $ 12,382 800000044056 332100228530 ATERET TORAH CENTER $ 28,962 800000051126 222201155866 AUGUSTINIAN ACADEMY-ELEMENTARY $ 22,021 800000042667 342800226480 BAIS YAAKOV ACADEMY FOR GIRLS $ 103,321 800000087003 342700226221 BAIS YAAKOV ATERES MIRIAM $ 3,683 800000043817 331500229003 BAIS YAAKOV FAIGEH SCHONBERGER OF ADAS YEREIM $ 5,306 800000039002 500401229384 BAIS YAAKOV OF RAMAPO $ 4,980 800000070471 590501226076 BAIS YAAKOV OF SOUTH FALLSBURG $ 3,390 800000044016 332100229811 BARKAI YESHIVA $ 58,076 800000044556 331800809307 BATTALION CHRISTIAN ACADEMY $ 7,522 800000044120 332000999653 BAY RIDGE PREPARATORY SCHOOL -

Annual Report 2015

Annual Report 2015 - 2016 From the President and Executive Director Describing the condition of world Jewry in the aftermath of World War II, the twentieth century theologian Eliezer Berkovits observed that the Jewish people stood “between yesterday and tomorrow.” On the one hand, “yesterday” was no more. On the other hand, the future was unclear; “tomorrow” had not yet dawned. BJE shapes the present of Jewish education in Los Angeles - with the support of institutional and individual partners - by drawing from the rich wisdom of yesterday, helping learners experience a meaningful present and contribute to a better tomorrow. Through engaging children and families in Jewish education, enhancing the quality of Jewish education and expanding access to Jewish learning opportunities, BJE helps build today’s Jewish educational experiences, enabling successive generations to create a more robust tomorrow. The pages of this Annual Report share several aspects of this work. From early childhood education, to Dr. Alan M. Spiwak innovative approaches at (complementary) religious schools; from multiple generations experiencing and reflecting on “March of the Living” to college students engaging with issues in Jewish education and communal service as BJE Lainer Interns; from initiatives to help families access Jewish day school education to programs that strengthen the teaching of Hebrew, BJE is, with your help, building the present and shaping the future. Thank you for your partnership as a builder of Jewish education. With best wishes in 2016-2017 (5777). Sincerely, Dr. Alan M. Spiwak Dr. Gil Graff President Executive Director Dr. Gil Graff BJE 2015-2016 Board of Directors Table of Contents Herb Abrams* Marjorie Gross Craig Rutenberg Michael Adler Eileen Horowitz Jay Sanders 3 ......................... -

State of the Field Teacher As Text

חורף תשע"ד • WINTER 2013 Day School Teachers Roundtable: 14 State of the Field 42 Teacher as Text Mobile Solutions for Active Families. Parents are on the go. That’s why we’ve made the FACTS system even more accessible. Parents can make payments, review account changes, view their payment schedule, and more—right from their preferred mobile device. Families can also get support from FACTS 24/7 on their timetable. Contact us today to learn how FACTS’ technology makes tuition management easy for families. Tuition Management // Grant & Aid Assessment // Donor Services // 877.606.2587 // FACTSmgt.com Facts_Haiydon-Ad_0422.indd 1 4/22/13 1:50 PM in this issue: RAVSAK News COLUMNS: From the Editor, page 5 • From the Desk of Rebekah Farber, RAVSAK Chair, page 6 • Good & Welfare, page 7 • Dear Cooki, page 8 • Jonathan Woocher, Keeping the Vision, p. 30 • eRAVSAK Highlights, page 51 • Welcoming New Team Members, page 66 PROGRAMS: Hebrew Language Council, page 7 • Head of School Professional Excellence Project, page 13 • Sulam 2.0 and Alumni, page 23 • Teacher Day at the Conference, page 25 • Reshet RAVSAK, page 31 • RAVSAK/Pardes Jewish Day School Leadership Conference, page 32-33 • RAVSAK Board Retreat, page 41 • Enrollment Study, page 44 • Moot Beit Din, page 45 • Hebrew Poetry Contest, page 46 • Jewish Art Contest, pages 56-57 THE PROFESSION Inverting the Triangle: 10 Reimagining This So-Called Profession Barbara Rosenblit 14 State of the Field: Sharon Feiman-Nemser, Amy Ament, Miriam Heller Stern, Teacher Training for Day Schools Rona Novick, -

2017-2018 Financial and Strategic Highlights

Financial Highlights Mazel Day School Strategic & Financial 2017-18 Annual Expenses MDS Annual Expense Highlights (Revenue Ratio) Breakdown $855K 2017-2018 SCHOOL YEAR OPERATIONS Security, rent, lunch, 19% maintenance, supplies GAP ANNUAL BUDGET $945K 81% $4,070K ADMINISTRATION: EXPENSES Educational Leadership, COVERED BY Management, Office TUITION Staff $795K $2,275K ANNUAL CAMPAIGN GOAL TEACHERS: Main Teachers, Assistants, Specialty Teachers “Long ago the Jewish people came to the conclusion that to defend a country you need an army. But to defend a civilization you need schools. The single most important social institution is the place where we hand on our values to the next generation — where we tell our children where we’ve come from, what ideals we fought for, and what we learned on the way. Schools are where we make children our parents in the long and open-ended task of making a more gracious world.” - JONATHAN SACKS To empower our students with the tools they will need as they Our embark on their Life Journeys. Enriched by Judaism’s values and wisdom, we cultivate within our students the ability to Mission be good students, good friends, and good people, providing a secure foundation which prepares children to thrive in a complex and changing world. Educational Highlights Strategic Goals STEM Learning Enrichment Program 1. Sustain annual growth in student body enrollment Singapore Mathematics 2. Maintain and improve high quality of education Ongoing professional development 3. Ensure need-based scholarship distribution Judaic studies 4. Build relationships with top-rank High Schools in NYC Google Classroom 5. Expand and improve current facilities FOSS (Full Option Science System) 6. -

UP School Accounts

Alachua Account Value Owner Name Reporting Entity ‐‐ Source of Funds Type of Account 105916441 $32.45 OCHWILLA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PTO, QSP INC ACCOUNTS PAYABLE 115227409 $5.07 LITTLE PIONEERS PRESCHOOL, COCA COLA REFRESHMENTS USA INC ACCOUNTS PAYABLE 115227410 $10.76 LITTLE PIONEERS PRESCHOOL, COCA COLA REFRESHMENTS USA INC ACCOUNTS PAYABLE 108967892 $27.15 POT OF GOLD HIGH SPRINGS FL, COCA COLA REFRESHMENTS USA INC ACCOUNTS PAYABLE 102962446 $120.00 LADY RAIDER BASKETBALL‐SANTA FE HIGH S, ALACHUA UTILITY CITY OF ACCOUNTS PAYABLE 113684402 $563.43 SANTA FE HIGH SCHOOL, COCA COLA REFRESHMENTS USA INC ACCOUNTS PAYABLE 120116250 $12.83 WALDO COMMUNITY SCHOOL, COCA COLA REFRESHMENTS USA INC CREDIT BALANCES ON ACCOUNTS 113684650 $24.75 WALDO COMMUNITY SCHOOL, COCA COLA REFRESHMENTS USA INC ACCOUNTS PAYABLE 111036494 $98.74 TRILOGY SCHOOL, COMPASS GROUP USA INC ACCOUNTS PAYABLE 104238730 $12.46 TRILOGY SCHOOL, BELLSOUTH TELECOMMUNICATIONS INC UTILITY DEPOSITS 6707767 $25.88 SUWANNEE CO BD OF PUB INST, AFLAC OF COLUMBUS 121223784 $53.79 SUCCESSFUL KIDS ACADEMY, PRIME RATE PREMIUM FINANCE CORPORATION REFUNDS 112909067 $175.00 ARCHER COMMUNITY SCHOOL, TIME INC SHARED SERVICES CREDIT BALANCES ON ACCOUNTS 122494000 $177.94 ARCHER COMMUNITY SCHOOL, DRUMMOND COMMUNITY BANK CASHIERS CHECKS 120115254 $18.34 ARCHER COMMUNTIY SCHOOL, COCA COLA REFRESHMENTS USA INC CREDIT BALANCES ON ACCOUNTS 122294130 $24.25 ARCHER COMMUNTIY SCHOOL, COCA COLA REFRESHMENTS USA INC CREDIT BALANCES ON ACCOUNTS 100388385 $51.60 FLOWERS MONTESSORI ACADEMY, LIFETOUCH NATIONAL -

Engaging Educating and Inspiring Young Jewish Minds

Engaging Educating and Inspiring Young Jewish Minds 2008-2012 summary report Dear Colleagues, Young Jews engaging in ongoing Jewish learning and choosing to live vibrant Jewish lives For seven years, the Jim Joseph Foundation has partnered with effective, forward thinking Investing in promising Table of Contents organizations to realize this vision. Our work is guided by a mission that is simultaneously characterized by simplicity and Our Vision 2 challenge: To foster compelling, effective Jewish learning experiences for young Jews in the United States. This mission speaks to the values and strong Jewish identity of the Jewish education grant Fufilling Our Mission 4 Foundation’s founder, Jim Joseph, who passed away in 2003. Increase the Number and In this report, we share stories of grantee successes from 2008 to 2012. The stories showcase Quality of Jewish Educators p. 5 grantees’ achievements, anticipate future accomplishments, and reflect the Foundation’s Expand Effective Jewish Learning strategically-driven grantmaking process. Each initiative or program is developed and The Jim Joseph Foundation for Youth and Young Adults p. 11 implemented with explicit short-term and long-term goals and accompanied by evaluation. initiatives Build a Strong Field of This report also tells a larger story about where we are as a Foundation and our evolution Jewish Education p. 24 over the last seven years. Having granted more than $270 million, we are now in a position of great responsibility. Lessons learned guide our grantmaking. Equally as important is partners with effective Grant Listings 34 sharing these lessons with other funders and those in the field.