Monuments and Markers Stewardship Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 1999 Meeting Sundance, Wyoming April 23, 1999

Wyoming Association of Professional Archaeologists Minutes of the Spring 1999 Meeting Sundance, Wyoming April 23, 1999 Executive Committee Meeting The agenda for the Wyoming Association of Professional Archaeologists Business Meeting, scheduled for the afternoon of Friday, April 23, 1999 was discussed. Issues to be presented include the Secretary's Report, the Treasurer's Report, agency reports, old business including the outcome of the reorganization of the Wyoming Department of Commerce, nomination of officers, a discussion of the declining WAPA membership, any new business, and the location of the Fall 1999 WAPA business meeting which has already been scheduled for Friday, September 17, 1999 in Rock Springs in association with the events and activities for Wyoming Archaeology Awareness Month. Business Meeting PRESIDING: Paul Sanders, President CALL TO ORDER: The meeting was called to order at 1:30 P.M. SECRETARY'S REPORT: Minutes of the Fall 1998 WAPA meeting were distributed. No suggestions for changes were made. The group discussed the need to announce meetings earlier than has occurred recently. We have traditionally relied on the WAPA Newsletter to announce the time and location of the next meeting about a month in advance, but given the lateness of recent issues, this has not happened. Because of the early date of the next meeting, a meeting announcement will be prepared soon and e-mailed to everyone who has an e-mail address on file and send it via regular mail to those who don't. It was also noted that arrangements are being made for a special room rate for WAPA members at the Outlaw Inn in Rock Springs for the September meeting. -

Fort Laramie Nationa Monument

R n the P 'os i l ui s qf ost p ta . T'E CO'ER Con ten ts ' Entitled Fort Laramie or Sublettes Fort near ' the Nebraska, or Platte River, the sketch repro The Old Guardhouse duce d here was originally made in watercolor by Fur-Trading Era Alfred Miller (1 8 1 0 an American artist who Fort Laramie as a Pioneer Post accompanied the expedition of Sir William Drum 1 837 1 Fort Laramie as a Military Post mond Stewart to the West in and 838 . The Fort Laramie Today scene depicted shows a colorful Indian encamp Allied Sites of Interest ment in front of the palisades an d blockhouses of old Fort Laramie . The sketch is from the Alfred l Mi ler Collection in the possession of Mrs . Clyde Porter , Kansas City, Mo . , and reproduced with her permission . UN I TED STATE S D EPARTM E NT O F TH E I NTER I O R A LD C 'E Secretaz O . H R L I S , gy AT I O NAL PAR ' SER 'I C E NE'TO B Da n y N N . n D re r , i cto Fort Laramie N ation a Mon u me n t NO 'ISTORIC SITE in the Rocky Mountain region is Others seeking adventure or a better and more I of . ts u more important than that Fort Laramie fruitf l life , found protection and supplies at Fort as - as story fur trading station and military post Laramie , the great way station on the road to the its epitomizes the history of the successive stages by West . -

Wyoming SCORP Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2014 - 2019 Wyoming Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) 2014-2019

Wyoming SCORP Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2014 - 2019 Wyoming Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) 2014-2019 The 2014-2019 Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan was prepared by the Planning and Grants Section within Wyoming’s Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources, Division of State Parks, Historic Sites and Trails. Updates to the trails chapter were completed by the Trails Section within the Division of State Parks, Historic Sites and Trails. The Wyoming Game and Fish Department provided the wetlands chapter. The preparation of this plan was financed through a planning grant from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior, under the provision of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965 (Public Law 88-578, as amended). For additional information contact: Wyoming Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources Division of State Parks, Historic Sites and Trails 2301 Central Avenue, Barrett Building Cheyenne, WY 82002 (307) 777-6323 Wyoming SCORP document available online at www.wyoparks.state.wy.us. Table of Contents Chapter 1 • Introduction ................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 2 • Description of State ............................................................................. 11 Chapter 3 • Recreation Facilities and Needs .................................................... 29 Chapter 4 • Trails ............................................................................................................ -

The Mormon Trail

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2006 The Mormon Trail William E. Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hill, W. E. (1996). The Mormon Trail: Yesterday and today. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MORMON TRAIL Yesterday and Today Number: 223 Orig: 26.5 x 38.5 Crop: 26.5 x 36 Scale: 100% Final: 26.5 x 36 BRIGHAM YOUNG—From Piercy’s Route from Liverpool to Great Salt Lake Valley Brigham Young was one of the early converts to helped to organize the exodus from Nauvoo in Mormonism who joined in 1832. He moved to 1846, led the first Mormon pioneers from Win- Kirtland, was a member of Zion’s Camp in ter Quarters to Salt Lake in 1847, and again led 1834, and became a member of the first Quo- the 1848 migration. He was sustained as the sec- rum of Twelve Apostles in 1835. He served as a ond president of the Mormon Church in 1847, missionary to England. After the death of became the territorial governor of Utah in 1850, Joseph Smith in 1844, he was the senior apostle and continued to lead the Mormon Church and became leader of the Mormon Church. -

WYOMING Adventure Guide from YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK to WILD WEST EXPERIENCES

WYOMING adventure guide FROM YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK TO WILD WEST EXPERIENCES TravelWyoming.com/uk • VisitTheUsa.co.uk/state/wyoming • +1 307-777-7777 WIND RIVER COUNTRY South of Yellowstone National Park is Wind River Country, famous for rodeos, cowboys, dude ranches, social powwows and home to the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho Indian tribes. You’ll find room to breathe in this playground to hike, rock climb, fish, mountain bike and see wildlife. Explore two mountain ranges and scenic byways. WindRiver.org CARBON COUNTY Go snowmobiling and cross-country skiing or explore scenic drives through mountains and prairies, keeping an eye out for foxes, coyotes, antelope and bald eagles. In Rawlins, take a guided tour of the Wyoming Frontier Prison and Museum, a popular Old West attraction. In the quiet town of Saratoga, soak in famous mineral hot springs. WyomingCarbonCounty.com CODY/YELLOWSTONE COUNTRY Visit the home of Buffalo Bill, an American icon, at the eastern gateway to Yellowstone National Park. See wildlife including bears, wolves and bison. Discover the Wild West at rodeos and gunfight reenactments. Hike through the stunning Absaroka Mountains, ride a mountain bike on the “Twisted Sister” trail and go flyfishing in the Shoshone River. YellowstoneCountry.org THE WORT HOTEL A landmark on the National Register of Historic Places, The Wort Hotel represents the Western heritage of Jackson Hole and its downtown location makes it an easy walk to shops, galleries and restaurants. Awarded Forbes Travel Guide Four-Star Award and Condé Nast Readers’ Choice Award. WortHotel.com welcome to Wyoming Lovell YELLOWSTONE Powell Sheridan BLACK TO YELLOW REGION REGION Cody Greybull Bu alo Gillette 90 90 Worland Newcastle 25 Travel Tips Thermopolis Jackson PARK TO PARK GETTING TO KNOW WYOMING REGION The rugged Rocky Mountains meet the vast Riverton Glenrock Lander High Plains (high-elevation prairie) in Casper Douglas SALT TO STONE Wyoming, which encompasses 253,348 REGION ROCKIES TO TETONS square kilometres in the western United 25 REGION States. -

Friends O F SAINT-GAUDENS

friends OF SAINT-GAUDENS CORNISH I NEW HAMPSHIRE I SPRING / SUMMER 2011 IN THIS ISSUE The Ames Monument I 1 The Puritan I 5 New Exhibition in The Little Studio I 6 David McCullough “The Great Journey...” I 6 Saint-Gaudens iPhone App I 8 DEAR FRIENDS, We want to announce an exciting new development for lovers (and soon-to-be lovers) of Saint-Gaudens! The park, with support from the Memorial, has devel- oped one of the first ever iPhone apps for a national park. This award-winning app provides users with a wealth of images and information on the works of Saint-Gaudens, audio tours of the museum buildings and grounds, information on contemporary exhibitions as well as other information Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Oliver and Oakes Ames Monument, 1882. on artistic, architectural and natural resources that greatly enhance a visitor’s experience at the park. (See page 7 for AUGUSTUS SAINT-GAUDENS’ more information on the app). COLLABORATION WITH H.H. RICHARDSON: OLIVER AND OAKES AMES MONUMENT Another exciting educational project THE underway is a book about Saint-Gaudens’ In a broad expanse of southeastern Wyoming lies a lonely monument, Puritan and Pilgrim statues. The book, an anomaly that arises from the desolate landscape. Measuring sixty feet generously underwritten by the Laurence square at its base and standing sixty feet high, the red granite pyramid Levine Charitable Fund, is due out in structure is known as the Oliver and Oakes Ames Monument, after the two June (see page 5 for more information), brothers to whom it is dedicated. -

SPRING HILL RANCH Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service______National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) 0MB No. 1024-0018 SPRING HILL RANCH Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_______________________________ National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Spring Hill Ranch Other Name/Site Number: Deer Park Place; Davis Ranch; Davis-Noland-Merrill Grain Company Ranch; Z Bar Ranch 2. LOCATION Street & Number: North of Strong City on Kansas Highway 177 Not for publication: City/Town: Strong City Vicinity: X State: Kansas County: Chase Code: 017 Zip Code: 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): __ Public-Local: __ District: X Public-State: __ Site: __ Public-Federal: Structure: __ Object: _ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 8 _1_ buildings __ sites _5_ structures _ objects 14 12 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 2 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing :N/A Designated a NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK on NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) 0MB No 1024-0018 SPRING HILL RANCH Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

2021 Adventure Vacation Guide Cody Yellowstone Adventure Vacation Guide 3

2021 ADVENTURE VACATION GUIDE CODY YELLOWSTONE ADVENTURE VACATION GUIDE 3 WELCOME TO THE GREAT AMERICAN ADVENTURE. The West isn’t just a direction. It’s not just a mark on a map or a point on a compass. The West is our heritage and our soul. It’s our parents and our grandparents. It’s the explorers and trailblazers and outlaws who came before us. And the proud people who were here before them. It’s the adventurous spirit that forged the American character. It’s wide-open spaces that dare us to dream audacious dreams. And grand mountains that make us feel smaller and bigger all at the same time. It’s a thump in your chest the first time you stand face to face with a buffalo. And a swelling of pride that a place like this still exists. It’s everything great about America. And it still flows through our veins. Some people say it’s vanishing. But we say it never will. It will live as long as there are people who still live by its code and safeguard its wonders. It will live as long as there are places like Yellowstone and towns like Cody, Wyoming. Because we are blood brothers, Yellowstone and Cody. One and the same. This is where the Great American Adventure calls home. And if you listen closely, you can hear it calling you. 4 CODYYELLOWSTONE.ORG CODY YELLOWSTONE ADVENTURE VACATION GUIDE 5 William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody with eight Native American members of the cast of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, HISTORY ca. -

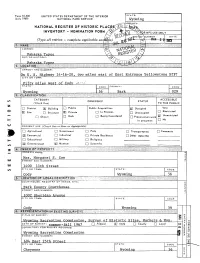

Register Cliff AND/OR HISTORIC

Form 10-300 (Dec. 1968) Wyoming COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Platte INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) lililii Register Cliff AND/OR HISTORIC: STREET ANDNUMBER: NW%, NW%, Section 7; T. 26 N., R. 6J5.W. CITY OR TOWN: Guernsey COUNTY: Wyoming 49 Platte 031 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC Z 'Public District CD Building CD D Public Acquisition: Occupied CD Yes: O Site [X| Structure Private a In Process [~~1 Unoccupied B Restricted CD Both Being Considered I I Unrestricted |y] Object Preservation work in progress |~j No: D u PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) ID Agricultural [ | Government d) Park Transportation | | Comments I f Commercial CD Industrial CD Private Residence CD Other (Specify) C7] _____ Educational CD Military CD Religious Ranch Property Entertainment | | Museum CD Scientific State Historic Site OWNERS NAME: State of Wyoming, administered by the Wyoming Recreation Commission LJJ STREET AND NUMBER: W 604 East 25th Street to CITY OR TOWN: Cheyenne Wyoming 49 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Wyoming Recreation Commission STREET AND NUMBER: 604 East 25th Street CITY OR TOWN: Cheyenne Wyoming 49 APPROXIMATE ACREAGE OF NOMINATED PROPERTY: TITLE OF SURVEY: Evaluation and Survey of Historic Sites in Wyoming DATE OF SURVEY: 1963 Federal State CD County CD Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: National Park Service STREET AND NUMBER: Midwest Regional Office, Department of Interior CITY OR TOWN: Washington District of Columbia 08 : :vx :: •••:•' :•. ' >. •'• ' '••'• . :-: :•: .•:• x '.x..;:/ :" .'.:.>- • i :"S:S'':xS:i;S:5;::::BS m. '&•• ?&*-ti':W$wS&3^$$$s (Check One) CONDITION Excellent Q Good [x Fair Q Deteriorated Q Ruins a Unexposed a (Check One) (Check One) INTEGRITY Altered D Unaltered ^] Moved | | Original Site [^j DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Register Cliff consists of a soft, chalky, limestone precipice rising over 100 feet above the valley floor of the North Platte River. -

The United States Army As a Constabulary on the Northern Plains

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 1993 The United States Army as a Constabulary on the Northern Plains Larry D. Ball Arkansas State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Ball, Larry D., "The United States Army as a Constabulary on the Northern Plains" (1993). Great Plains Quarterly. 772. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/772 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE UNITED STATES ARMY AS A CONSTABULARY ON THE NORTHERN PLAINS LARRY D. BALL With the formation of the United States mili Hills mining camps and looted stagecoaches in tary establishment in the late eighteenth cen alarming numbers; brazenly robbed Union Pa tury, the new army undertook many services in cific trains and threatened to disrupt their sched the developing republic, including several asso ules; plundered Sioux, Arapahoe, and other ciated with the frontier movement. While the Indian horse herds as well as those of white army considered the suppression of hostile Indi settlers; and even preyed upon military prop ans its primary mission in the West, its soldiers erty. This lawless onslaught threatened to routinely supported civilian law enforcement overwhelm the nascent law enforcement agen authorities. After the Civil War, white crimi cies of Wyoming, Dakota, and neighboring nals accompanied other American frontiers districts. -

L$Y \Lts^ ,Atfn^' Jt* "NUMBER DATE (Type All Entries Complete Applicable Seqtwns) N ^ \3* I I A\\\ Ti^ V ~ 1

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Wyoml ng NATIONAL REG ISTER OF HISTORIC PLAC^r^Sal^^ V INVENTOR Y - NOMINATION FORM X/^X^|^ ^-£OR NPS USE ONLY L$y \ltS^ ,atfN^' Jt* "NUMBER DATE (Type all entries complete applicable seqtwns) n ^ \3* I I A\\\ ti^ V ~ 1 COMMON: /*/ Pahaska Tepee \XA 'Rt-^ / AND/OR HISTORIC: Xrfr /N <'X5^ Paha.ska Tpppp 3&p&!&ji;S:ii^^^^^ #!!8:&:;i&:i:;*:!W:li^ STREET ANDNUMBER: On U. S. Highway 14-16-20, two miles east of East Entrance Yellowstone N?P? CITY OR TOWN: Fifty miles west of Codv xi --^ STATE CODE COUNTY: CODE 029 TV "" Wyoming 56 Park ^'.fi:'-'-'-'A'''-&'&i-'-&'-i'-:&'-''i'-'-'^ flli i^^M^MI^M^m^^w^s^M^ CATEGORY TATUS ACCESS.BLE OWNERSHIP S (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC n District [x] Building D Public Public Acquisition: g] Qcc upied Yes: . n Restricted [X] Site Q Structure S Private D In Process r-] y no ccupied |y] Unrestricted D Object Q] Both Q Being Considered r i p res ervation work in progress 1 ' PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) \ 1 Agricultural Q Government [J Park Q Transp ortation 1 1 Comments r (X) Commercial D Industrial Q Private Residence Q Other C Spftrify) PI Educational [~~l Mi itary fl Religious [j|] Entertainment ix] Mu seum i | Scientific .... .^ ....-- OWNER'S NAME: STATE: Mrs . Margaret S . Coe STREET AND NUMBER: 1400 llth Street CITY OR TOWN: STATE: CODE Cody Wyoming 56 piilllliliii;ltillli$i;lil^^ COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: TY:COUN Park County Courthouse STREET AND NUMBER: 1002 Sheridan Avenue Cl TY OR TOWN: STATE CODE Codv Wyoming 56 Tl TLE OF SURVEY: I NUMBERENTRY Wyoming Recreation Commission, Survey of Historic Sites, Markers & Mon. -

Road to Oregon Written by Dr

The Road to Oregon Written by Dr. Jim Tompkins, a prominent local historian and the descendant of Oregon Trail immigrants, The Road to Oregon is a good primer on the history of the Oregon Trail. Unit I. The Pioneers: 1800-1840 Who Explored the Oregon Trail? The emigrants of the 1840s were not the first to travel the Oregon Trail. The colorful history of our country makes heroes out of the explorers, mountain men, soldiers, and scientists who opened up the West. In 1540 the Spanish explorer Coronado ventured as far north as present-day Kansas, but the inland routes across the plains remained the sole domain of Native Americans until 1804, when Lewis and Clark skirted the edges on their epic journey of discovery to the Pacific Northwest and Zeb Pike explored the "Great American Desert," as the Great Plains were then known. The Lewis and Clark Expedition had a direct influence on the economy of the West even before the explorers had returned to St. Louis. Private John Colter left the expedition on the way home in 1806 to take up the fur trade business. For the next 20 years the likes of Manuel Lisa, Auguste and Pierre Choteau, William Ashley, James Bridger, Kit Carson, Tom Fitzgerald, and William Sublette roamed the West. These part romantic adventurers, part self-made entrepreneurs, part hermits were called mountain men. By 1829, Jedediah Smith knew more about the West than any other person alive. The Americans became involved in the fur trade in 1810 when John Jacob Astor, at the insistence of his friend Thomas Jefferson, founded the Pacific Fur Company in New York.