Fear and Hope in Angela Carter's Fictions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marxist Feminism and Postmodern Elements in Angela Carter's Nights

INFOKARA RESEARCH ISSN NO: 1021-9056 Marxist Feminism and Postmodern Elements in Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus R.Padhmavathi Ph.D Researchscholar Department of English Email id:[email protected] AnnamalaiUniversity ,Chidhambaram. Dr.A.Glory , Asst.professor, Department of English Annamalai University, Chidhambaram Abstract: This paper endeavors to examine critically and analytically how the Marxist feminism is developed in Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus (1984), and how the postmodernistic ideas in her mind. It sheds light on the feminine themes and concerns, and in this novel Angela Carter speaks out lots of feminine matters and moves around strongly in her mind. Her lasting fascination with femininity as vision has until then been understood mainly in terms of a feminist critical project which identifies and rejects male-constructed images of women as a form of false consciousness. Keywords: Feminism, Marxism, Carnivalisation, Postmodernism Marxist Feminism and Postmodern Elements in Angela Carter’s Nights At The Circus Angela Carter’s achievements asa feminist are clearly understood only if we look at her novels with postmodern eyes. Her novels make no sense unless they are given a postmodern reading which can extricate the challenging thoughts on the essence of womanhood that lie entangled in fantasies, dreams, myths, and parodies. Through reading the novels of Angela Carter, it is noticeable that she goes in the femininity track in her fictional writings. HerNights at the Circus is a novel about the ways in which these dominant, frequently male-centered discourses of power marginalize those whom society defines as freaks, madmen, clowns, the physically and mentally deformed, and, in particular, women, so that they may be contained and controlled because they are all possible sources of the disordered disruption of established power. -

The Quest for Female Empowerment in Angela Carter's Wise Children

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy “I AM NOT SURE IF THIS IS A HAPPY ENDING” THE QUEST FOR FEMALE EMPOWERMENT IN ANGELA CARTER’S WISE CHILDREN Supervisor: Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of Professor Marysa Demoor the requirements for the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels” by Aline Lapeire 2009-2010 Lapeire ii Lapeire iii “I AM NOT SURE IF THIS IS A HAPPY ENDING” THE QUEST FOR FEMALE EMPOWERMENT IN ANGELA CARTER’S WISE CHILDREN The cover of Wise Children (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007) Lapeire iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation could not have been written without the help of the following people. I would hereby like to thank… … Professor MARYSA DEMOOR for supporting my choice of topic and sharing her knowledge about gender studies. Her guidance and encouragement have been very important to me. … DEBORA VAN DURME and Professor SINEAD MCDERMOTT for their interesting class discussions of Nights at the Circus and Wise Children. Without their keen eye for good fiction, I might have never even heard of Angela Carter and her beautiful oeuvre. … Several very patient librarians at the University of Ghent. … A great deal of friends who at times mocked the idea of a „gender dissertation‟, yet always showed their support when it was due. I especially want to thank my loyal thesis buddies MAX DEDULLE and MARTIJN DENTANT. The countless hours we spent together while hopelessly staring at a world behind the computer screen eventually did pay off. Moreover, eternal gratitude and a vodka-Red Bull go out to JEROEN MEULEMAN who entirely voluntarily offered to read and correct my thesis. -

Feminist Subversion of Fairy-Tale Female Characters in Angela Carter's

100 ORIGINALNI NAUĈNI RAD DOI: 10.5937/reci1912100G UDC: 821.111.09-31 Karter A. 821.111.09:305-055.2"19" AnĊelka M. Gemović* University of Novi Sad Faculty of Philosophy FROM CAPTIVITY TO BESTIALITY: FEMINIST SUBVERSION OF FAIRY-TALE FEMALE CHARACTERS IN ANGELA CARTER’S “THE TIGER’S BRIDE” Abstract: This paper elaborates on Angela Carter‟s subversion of the fairy-tale genre in the tale from The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories titled “The Tiger‟s Bride”. The method of research combines researching relevant theoretical literature and thorough text analysis. The primary concern of this paper is the subversion of female characters in fairy tales as a means of advocating feminist attitudes. Relevant passages are used to exemplify Carter‟s feminism, with special reference to the subverted roles of the heroine of the tale. The female protagonist‟s transition from being a captive to becoming a beast is analysed, and her reinvented roles discussed and compared to the traits of the heroine from the classic Beauty and the Beast story written by De Beaumont. This is done in order to uncover the multilayered structure of Carter‟s work and hopefully determine the author‟s genuine purpose in subverting the fairy-tale genre as well as the message she wanted to convey. Key words: beast tales, The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories, Carter‟s feminism, Beauty and the Beast, women empowerment. * [email protected] 2 0 1 9 FROM CAPTIVITY TO BESTIALITY: FEMINIST SUBVERSION OF FAIRY- TALE FEMALE CHARACTERS IN ANGELA CARTER’S “THE TIGER’S BRIDE” 101 INTRODUCTION Angela Carter was an English novelist, short story writer, poet, journalist, professor and critic known for her feminist and nonconformist attitudes that she deliberately conveyed throughout her work. -

The Consumption of Angela Carter

The Consumption of Angela Carter: Women, Toody and Power EMMA PARKER A great writer and a great critic, V. S. Pritchett, used to sav that he swallowed Dickens whole, at the risk of indigestion. I swallow Angela Carter whole, and then I rush to buy Alka Seltzer. The "minimalist" nouvelle cuisine alone cannot satisfy my appetite for fiction. I need a "maximalist" writer who tries to tell us many things, with grandiose happenings to amuse me, extreme emotions to stir my feelings, glorious obscenities to scandalise me, brilliant and malicious expressions to astonish me. (Almansi 217) L Vs GUIDO ALMANSI suggests, consuming Angela Carter's fic• tion is simultaneously satisfying and unsettling. This is partly because, as Hermione Lee has commented, Carter "was always in revolt against the 'tyranny of good taste'" (316). As a cham• pion of moral pornography, a cultural dissident who dared to disparage Shakespeare, and a culinary iconoclast who criticised the highly-esteemed cookery writer Elizabeth David, Carter out• raged many people. Yet this impiety also gives her work its ap• peal.1 Like the critical essays, her fiction is deliciously "improper" in that it interrogates and rejects what Hélène Cixous calls the realm of the proper, a masculine economy based on the principles of authority, domination and owner• ship — a realm in which, disempowered and dispossessed, women are without property ("Castration" 42, 50). Her fiction has an unsettling effect precisely because Carter seeks to "up• set" the patriarchal order, in part through her representation of consumption, which, by revealing and refiguring the relation• ship between women, food, and power, challenges the struc• tures that underpin patriarchy. -

Identity I N Angela Carter's Nights at the Circus and Wise Children

Performing (and) Identity In Angela Carter's Nights at the Circus and Wise Children Janine Root @ B .A. B. Ed A cnesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English, Lakehead University, Thnder Bay, Ontario, 1999 National Library BibliotMy nationale 1*1 ofCanada du Cana a Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wauinglm Strwt 385. rue WdlingWn WONK1AW o(I.waON K1AW Cwudr CMed. The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence dowing the exclusive pennettant a la National Libmy of Cana& to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduke, prster, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fonnat electronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protege cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent &e imprimes reproduced without the author' s ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. Abstract In her last two novels, Nights at the Circus and Wise Children, Angela Carter examines some of the complex factors involved in the construction of identity, both within the fictional world, and for readers in their interaction with 'Le .jn-74 ,., I ,,,, 2f the fictix. 35 zhese f3ctxs, qezier is cf primary importance. -

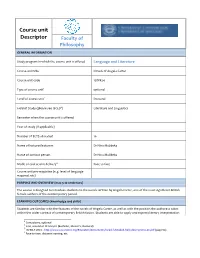

Course Unit Descriptor

Course unit Descriptor Faculty of Philosophy GENERAL INFORMATION Study program in which the course unit is offered Language and Literature Course unit title Novels of Angela Carter Course unit code 15DFk24 Type of course unit1 optional Level of course unit2 Doctoral Field of Study (please see ISCED3) Literature and Linguistics Semester when the course unit is offered Year of study (if applicable) Number of ECTS allocated 10 Name of lecturer/lecturers Dr Nina Muždeka Name of contact person Dr Nina Muždeka Mode of course unit delivery4 Face to face Course unit pre-requisites (e.g. level of language required, etc) PURPOSE AND OVERVIEW (max 5-10 sentences) The course is designed to introduce students to the novels written by Angela Carter, one of the most significant British female authors of the contemporary period. LEARNING OUTCOMES (knowledge and skills) Students are familiar with the features of the novels of Angela Carter, as well as with the position the authoress takes within the wider context of contemporary British fiction. Students are able to apply and express literary interpretation 1 Compulsory, optional 2 First, second or third cycle (Bachelor, Master's, Doctoral) 3 ISCED-F 2013 - http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Documents/isced-f-detailed-field-descriptions-en.pdf (page 54) 4 Face-to-face, distance learning, etc. effectively. SYLLABUS (outline and summary of topics) Lectures Angela Carter, contemporary British novel, feminist theory and engaged writing. Shadow Dance as parodic contemporary gothic fiction. Let’s begin countering patriarchal stereotypes: The Magic Toyshop. Several Perceptions: generation gap and the counterculture of the 60s. -

Angela Carter's Nights at the Circus: a Feminist Spatial Journey to Emancipation and Gender Justice

International Review of Literary Studies IRLS 2 (2) December 2020 ISSN: Online 2709-7021; Print 2709-7013 Angela Carter’s Nights at The Circus: A Feminist Spatial Journey to Emancipation and Gender Justice Dr. Wiem Krifa1 International Review of Literary Studies Vol. 2, No. 2; December 2020, pp. 46- 61 Published by: MARS Research Forum Received: October 10, 2020 Accepted: December 15, 2020 Published: December 22, 2020 Abstract Mobility can be considered as a natural characteristic of human beings, regardless of gender, sex or geographical roots. Within the feminist postmodern context, mobility ushers women in a new world based on gender equality and tolerance. Angela Carter’s Nights at The Circus displays a female character who achieves her New Woman status while traveling from one country to another, as a circus aerialist. Fevvers’ train journey from London to Siberia, together with her lover, empowers her female being. Space proves to be a substantial prerequisite for the achievement of the human subjectivity whether the female or the masculine one. Carter’s heroine succeeds to overcome the patriarchal misogynist attitude that surrounds her professional career and ends by achieving her female subjectivity. Besides, she triumphs to metamorphose Walser from the traditional male figure who looks to debunk Fevvers ‘claimed bird origin, into the new postmodern man who believes in gender equality and surrenders to Fevvers’love. All along their journey, Fevvers, Walser and other female characters, undergo a deep transformation at the level of their personal growth and subjectivities. They overcome their culturally internalized believes, to be prepared for a life based on equal principles and free from the imposed patriarchal cultural constraints. -

Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives

Postmodern Openings ISSN: 2068 – 0236 (print), ISSN: 2069 – 9387 (electronic) Coverd in: Index Copernicus, Ideas. RePeC, EconPapers, Socionet, Ulrich Pro Quest, Cabbel, SSRN, Appreciative Inquery Commons, Journalseek, Scipio EBSCO Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives Ileana BOTESCU – SIRETEANU Postmodern Openings, 2010, Year 1, VOL.3, September, pp: 93-138 The online version of this article can be found at: http://postmodernopenings.com Published by: Lumen Publishing House On behalf of: Lumen Research Center in Social and Humanistic Sciences BOTESCU–SIRETEANU, I.,(2010) Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives, Postmodern Openings, Year 1, Vol 3, September, 2010, pp: 93-138 Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives Ileana BOTESCU – SIRETEANU8 Abstract In a world where meaning has been deconstructed and reconstructed, where centers have lost their hegemony and notions such as truth, knowledge or history have been rendered relative by the ongoing ontological enquiry of the postmodern ideology, it is baffling to remark that not only in literature, but also in other fields that make use of discourses, there has been a return to and a reconsideration of the narrative. Nowadays, one can easily observe the narrative drive that enlivens various discourses, from the medical one to the one used in the academe or in official governmental documents. Brian McHale has even referred to the „narrative turn” in literary theory which, according to him, seems to answer to the loss of the metaphysical (McHale 4). Keywords: narrative turn, feminism, narrative dynamics, 8 Ileana BOTESCU – SIRETEANU – “Transilvania” University from Brasov, Romania, Email Address: [email protected]. -

Women As Embodied Social Subjects in Angela Carter's

ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPER 821.111.09-31 К АРТЕР А. DOI:10.5937/ ZRFFP47-14868 TATJANA B. M ILOSAVLJEVIĆ1 EDUCONS U NIVERSITY, S REMSKA K AMENICA “THE BODY DOES MATTER”: WOMEN AS EMBODIED SOCIAL SUBJECTS IN ANGELA CARTER’S NIGHTS AT THE CIRCUS ABSTRACT. Postmodernism posed a crucial ontological challenge to reality, questioning what constitutes the real world, simultaneously interrogating the horizon of representation of this unstable reality in fiction. Feminism on the other hand equipped us with critical tools for interpreting the reality of being in the world in a gendered body, as well as with a conceptual apparatus for inter- preting the manifold institutional and private oppressions of women’s bodies that play out in women’s daily lives and in the discourses that shape them, literary discourse being one of them. This paper argues that Angela Carter’s 1984 novel Nights at the Circus , which is widely held as a postfemi- nist text due to its narrative commitment to transcending gender binaries, essentially uses the strategies of postmodern storytelling and characteriza- tion in order to explore women’s embodied potentialities of agency i.e. their construction of subjectivity through body. We will argue that the hybrid magic realist narrative constructs Fevvers’ body as a titillating postmodern performance, ontologically illusive and elusive, yet it grounds that same body in various socially effected predicaments and experiences that serve to show that even in the midst of a play of signifiers, in Patricia Waugh’s words, “the body does matter, at least to what has been the dominant perspective within British female fiction” (Waugh, 2006, p. -

Literary Miscellany

Literary Miscellany A Selection from Recent Acquisitions and Stock Including Prose and Poetry from the 17th - 20th Centuries Association Copies and Letters Fine Printing, Illustrated Books, Film Material, And Varia of Other Sorts Catalogue 306 WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CT. 06511 USA 203.789.8081 FAX: 203.865.7653 [email protected] www.reeseco.com TERMS Material herein is offered subject to prior sale. All items are as described, but are consid- ered to be sent subject to approval unless otherwise noted. Notice of return must be given within ten days unless specific arrangements are made prior to shipment. All returns must be made conscientiously and expediently. Connecticut residents must be billed state sales tax. Postage and insurance are billed to all non-prepaid domestic orders. Orders shipped outside of the United States are sent by air or courier, unless otherwise requested, with full charges billed at our discretion. The usual courtesy discount is extended only to recognized booksellers who offer reciprocal opportunities from their catalogues or stock. We have 24 hour telephone answering and a Fax machine for receipt of orders or messages. Catalogue orders should be e-mailed to: [email protected] We do not maintain an open bookshop, and a considerable portion of our literature inven- tory is situated in our adjunct office and warehouse in Hamden, CT. Hence, a minimum of 24 hours notice is necessary prior to some items in this catalogue being made available for shipping or inspection (by appointment) in our main offices on Temple Street. We accept payment via Mastercard or Visa, and require the account number, expiration date, CVC code, full billing name, address and telephone number in order to process payment. -

Hamlet + Dracula & the Bloody Chamber

2 0 1 9 Hamlet Dracula & The Bloody Chamber EASTER WORK Tick when Week 1 – Securing the Knowledge complete D & TBC: Secure your knowledge - Use knowledge organisers to ensure you are secure on the basics Monday 8th - Make revision cards of any phrases that you like, knowledge April you feel is not secure (including the plot) and link to quotations from the texts - Watch Massolit on Dracula and TBC Hamlet: Secure your Knowledge - Secure your knowledge of the text and order of plot. Read over Tuesday 9th the scene notes you have. April - Group three quotations for each character - Five words for tone for each character - Massolit – John McCrea and the soliloquies Wednesday D & TBC: Re-read the introductions from both texts 10th April - Take notes and make revision cards as appropriate Hamlet: Critical Interpretations - Revise the critical interpretations on page 3-5. If you are unclear on these, make notes and revision cards. Thursday 11th - Have a well-phrased sentence you learn for each critic April - Link critical interpretation to film version and quotation from text - For fun extra revision – you could watch some of these interpretations! D & TBC Secure Critical Interpretations - Revise context booklets to ensure you have a sense of overview of interpretation over time. This will be helped by your recent read of the introductions. CORE KNOWLEDGE IS: Dracula – Stoker’s life, Daily Mail 1897, Punter, Frayling, Craft, Friday 12th Arata, Stoker’s ‘On Censorship’ essay. April TBC – Carter’s words about her work, Helen Simpson’s introduction, Marina Warner, Frayling, Helen Stoddart, Lorna Sage, Patricia Duncker - Watch/re-watch Massolit lectures to secure this knowledge - Have a well-phrased sentence you learn for each critic: test yourself. -

The Ritualization of Violence in <Em>The Magic Toyshop</Em>

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons English (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses 5-2016 The Ritualization of Violence in The Magic Toyshop Victor Chalfant Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/english_theses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Chalfant, Victor. The Ritualization of Violence in The Magic Toyshop. 2016. Chapman University, MA Thesis. Chapman University Digital Commons, https://doi.org/10.36837/chapman.000016 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in English (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ritualization of Violence in The Magic Toyshop A Dissertation by Victor Chalfant Chapman University Orange, CA Department of English Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English May 2016 Committee in charge: Kevin O’Brien, Ph.D., Chair Justine Van Meter, Ph.D. Joanna Levin, Ph.D. The dissertation of Victor Chalfant is approved. Kevin O’Brien, Ph.D., Chair Van Meter, Ph.D. Joanna Levin, Ph.D. May 2016 The Ritualization of Violence in The Magic Toyshop Copyright © 2016 by Victor Chalfant iii ABSTRACT The Ritualization of Violence in The Magic Toyshop by Victor Chalfant This dissertation will explore the way Philip treats puppets and masks as pseudo- sacred objects in order to maintain control in Angela Carter’s work The Magic Toyshop. To show the implications of the pseudo-sacred, I will use Violence and the Sacred by Rene Girard that examines the way primitive cultures are able to maintain order through particular religious beliefs and collective violence against a scapegoat.