Finding Pheasants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One Year in the Life of Museum Victoria July 04 – June 05

11:15:01 11:15:11 11:15:16 11:15:18 11:15:20 11:15:22 11:15:40 11:16:11 11:16:41 11:17:16 11:17:22 11:17:23 11:17:25 11:17:27 11:17:30 11:17:42 11:17:48 11:17:52 11:17:56 11:18:10 11:18:16 11:18:18 11:18:20 11:18:22 11:18:24 11:18:28 11:18:30 11:18:32 11:19:04 11:19:36 11:19:38 11:19:40 11:19:42 11:19:44 11:19:47 11:19:49 Museums Board of Victoria Museums Board 14:19:52 14:19:57 14:19:58 14:20:01 14:20:03 14:20:05 14:20:08ONE14:20:09 YEAR14:20:13 IN14:20:15 THE14:20:17 LIFE14:20:19 Annual Report 2004/2005 OF MUSEUM VICTORIA 14:20:21 14:20:22 14:20:25 14:20:28 14:20:30 14:20:32 14:20:34 14:20:36 14:20:38 14:20:39 14:20:42 14:20:44 Museums Board of Victoria JULY 04 – JUNE 05 Annual Report 2004/2005 14:21:03 14:21:05 14:21:07 14:21:09 14:21:10 14:21:12 14:21:13 10:08:14 10:08:15 10:08:17 10:08:19 10:08:22 11:15:01 11:15:11 11:15:16 11:15:18 11:15:20 11:15:22 11:15:40 11:16:11 11:16:41 11:17:16 11:17:22 11:17:23 11:17:25 11:17:27 11:17:30 11:17:42 11:17:48 11:17:52 11:17:56 11:18:10 11:18:16 11:18:18 11:18:20 11:18:22 11:18:24 11:18:28 11:18:30 11:18:32 11:19:04 11:19:36 11:19:38 11:19:40 11:19:42 11:19:44 11:19:47 11:19:49 05:31:01 06:45:12 08:29:21 09:52:55 11:06:11 12:48:47 13:29:44 14:31:25 15:21:01 15:38:13 16:47:43 17:30:16 Museums Board of Victoria CONTENTS Annual Report 2004/2005 2 Introduction 16 Enhance Access, Visibility 26 Create and Deliver Great 44 Develop Partnerships that 56 Develop and Maximise 66 Manage our Resources 80 Financial Statements 98 Additional Information Profile of Museum Victoria and Community Engagement Experiences -

Systematic Notes on Asian Birds. 65 a Preliminary Review of the Certhiidae 1

Systematic notes on Asian birds. 65 A preliminary review of the Certhiidae 1 J. Martens & D.T. Tietze Martens, J. & D. T. Tietze. Systematic notes on Asian birds. 65. A preliminary review of the Certhiidae. Zool. Med. Leiden 80-5 (17), 21.xii.2006: 273-286.— ISSN 0024-0672. Jochen Martens, Institut für Zoologie, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität, D-55099 Mainz, Germany. (e-mail: [email protected]). Dieter Thomas Tietze, Institut für Zoologie, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität, D-55099 Mainz, Ger- many. (e-mail: [email protected]). Key words: Certhiidae; species limits; systematics; taxonomy; First Reviser; eastern Palaearctic region; Indomalayan region; morphology; bioacoustics; molecular genetics. Recent proposed taxonomic changes in the Certhiidae are reviewed within the geographic scope of this series and their reliability is discussed in terms of the Biological Species Concept, with respect to sec- ondary contacts, bioacoustics, and molecular genetics. Certain hitherto unpublished data, useful for the understanding of taxonomic decisions, are included. In accordance with Article 24.2.3 of the Code one of us acts as First Reviser in selecting the correct spelling of the name of the recently described Chinese species. Introduction This contribution critically reviews, within the scope of this series, the few recent systematic and taxonomic papers on Asian treecreepers and their allies. Consequently it is purely descriptive in nature. Recommendations for taxonomic changes for nearly all the cases discussed here have been published elsewhere, most of them quite recently. As yet suffi cient time has not passed for completely objective review, nor for additional information to be discovered and presented in such cases. -

The Geladaindong Massif, Which Sits Roughly in The

348 T HE A MERICAN A LPINE J OURNAL , 2009 C LIMBS AND E XPEDITIONS : C HINA 349 The Geladaindong massif, which sits China roughly in the middle of the Tangula XINJIANG PROVINCE Shan, is 50km long (north-south) and Muzart Glacier, ascents and exploration. 20km wide (west-east). The highest The British–New Zealand expedition point, Geladaindong, is surrounded by of Paul Knott, Guy McKinnon, and more than 20 peaks higher than Bruce Normand gained a permit for 6,000m, most still unclimbed. French Xuelian Feng (6,628m), the dominant explorer Gabriel Bonvalot came to these peak in the eastern sector of the Chi - mountains at the source of the Yangtze nese Central Tien Shan, and one of few River (Chang Jiang) in 1890 and mountains in this region to have been referred to them as the Dupleix Range. climbed (by Japanese on their fourth attempt). The three acclimatized to altitudes of 5,400m Japanese first tried to negotiate a permit The east face of Peak 6,543m in the Geladaindong Massif. The on peaks on the north side of Muzart basin, after which Normand and McKinnon made a bid in 1982, but not until 1985 were they peak was climbed in 2007 by a Japanese expedition via the on the Xuelian side. After climbing questionable snow and reasonable ice slopes, they reached able to access the range and make the broad col on the right and the north-northwest ridge above. a point of listed height 6,332m, well east of the main summit of Xuelian Feng. An article by first ascent of Geladaindong, by the Courtesy of Tamotsu Nakamura and the Japanese Alpine News Knott and Normand on this little-known area extending east and south from 7,439m Pik Pobe - northwest ridge, approaching from the northeast. -

5 Days Chengdu Mount Siguniang Overland Tour

[email protected] +86-28-85593923 5 days Chengdu Mount Siguniang overland tour https://windhorsetour.com/kham-tour/chengdu-danba-mount-siguniang-tour Chengdu Danba Rilong Mount Siguniang Valleys Chengdu Travel far from the city's crowds and into the unspoiled wilderness of Mount Siguniang on this 5 day photography lovers tour. Relax yourself in the Sichuan blue sky with ominous clouds, snow cover peaks and the sound of rushing waterfalls. Type Private Duration 5 days Trip code WS-502 Price From ¥ 4,100 per person Itinerary The Mt. Siguniangshan ( Four-girl mountain) Scenic Area is an unspoiled wilderness park well-known throughout China, located in western Sichuan Province, near the town of Rilong in Aba. It includes one mountain - Mt. Siguniangshan, and three valleys -Shuangqiao Valley, Changping Valley, and Haizi Valley. The blue sky, clouds and mist, snow peaks, ancient cypress forests, rushing waterfalls, alpine meadows and local Tibetan and Qiang folk custom make this area like a fairyland. Day 01 : Chengdu / Danba Depart Chengdu in the early morning, drive to Danba (altitude 1,800m) by using the new tunnel at Balang mountain, it shortens the driving time to 6 hours. Danba, a county where you may see different Tibetan people and also their unique Danba ancient block towers. You will spend the night in Zhonglu village via a bumpy mountain road. You will explore Zhonglu village, crops fields and wait for the sunset. Overnight at Zhonglu local guest house. B=breakfast Day 02 : Sightseeing at Danba / Rilong (B) Enjoy the sunrise at Danba Zhonglu village if the weather permits, then head to visit the unique Danba Ancient block towers in Suopo, the grand and high one thousand years tower groups, the Dadu river valley, feeling and taste the folks and customs of Jiarong branch Tibet people. -

Wild China: Sichuan's Birds & Mammals

Wild China: Sichuan’s Birds & Mammals Naturetrek Tour Report 10 - 25 November 2018 Red Panda Tibetan Wolf Golden Snub-nosed Monkey Grandala Images and report compiled by Tim Melling Naturetrek Wolf’s Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Canada: The West Tour Participants: Tim Melling (Leader), Sid Francis (Local Guide) with seven Naturetrek clients Day 1 Saturday 10th November Depart London Heathrow on flight to Hong Kong. Day 2 Sunday 11th November The flights from Heathrow ran more or less to time and we arrived in Hong Kong early morning. From the windows of the airport we managed to see Black-eared Kites, Great Egrets, White Wagtails, and several Crested Mynas. We then boarded our somewhat delayed flight onwards to Chengdu, arriving about 13:30. Immigration took a little longer as new rules about fingerprints were brought in, but we were through in about 30 minutes. Sid was waiting for us by the exit and we were soon driving down to Dujiangyan. En route we spotted a few birds, the most conspicuous of which were many flocks of White-cheeked Starlings, Eastern Buzzards and Long-tailed Shrikes. We arrived at our hotel and met up with the rest of the party before going for our first spot of local birding. Up the nearby hill we found a large flock of Black-throated Tits and White-necked Yuhinas. We saw Pale-vented, Brown-breasted and Mountain Bulbuls, plus Chestnut-bellied Rock-thrushes and Great Barbets. -

Systematic Notes on Asian Birds. 65 a Preliminary Review of the Certhiidae 1

Systematic notes on Asian birds. 65 A preliminary review of the Certhiidae 1 J. Martens & D.T. Tietze Martens, J. & D. T. Tietze. Systematic notes on Asian birds. 65. A preliminary review of the Certhiidae. Zool. Med. Leiden 80-5 (17), 21.xii.2006: 273-286.— ISSN 0024-0672. Jochen Martens, Institut für Zoologie, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität, D-55099 Mainz, Germany. (e-mail: [email protected]). Dieter Thomas Tietze, Institut für Zoologie, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität, D-55099 Mainz, Ger- many. (e-mail: [email protected]). Key words: Certhiidae; species limits; systematics; taxonomy; First Reviser; eastern Palaearctic region; Indomalayan region; morphology; bioacoustics; molecular genetics. Recent proposed taxonomic changes in the Certhiidae are reviewed within the geographic scope of this series and their reliability is discussed in terms of the Biological Species Concept, with respect to sec- ondary contacts, bioacoustics, and molecular genetics. Certain hitherto unpublished data, useful for the understanding of taxonomic decisions, are included. In accordance with Article 24.2.3 of the Code one of us acts as First Reviser in selecting the correct spelling of the name of the recently described Chinese species. Introduction This contribution critically reviews, within the scope of this series, the few recent systematic and taxonomic papers on Asian treecreepers and their allies. Consequently it is purely descriptive in nature. Recommendations for taxonomic changes for nearly all the cases discussed here have been published elsewhere, most of them quite recently. As yet suffi cient time has not passed for completely objective review, nor for additional information to be discovered and presented in such cases. -

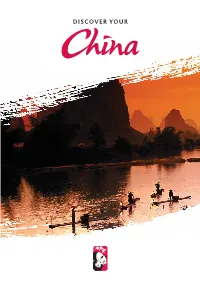

Discover Your 2 Welcome

DISCOVER YOUR 2 WELCOME Welcome to China Holidays We were immensely proud to be a Queen’s Award winner. We are an independently owned and managed company, founded in 1997, specialising in providing beset value travel arrangements to China only. Therefore we can offer you a highly personalised service with my colleagues in London and Beijing working hard to ensure you have an unforgettable, high quality and value-for-money holiday. It is because of our dedication to providing this that we have managed to prosper in one of the most competitive industries in the world. For thousands of years China has been the mysterious Middle Kingdom, the fabled land Welcome to my homeland and between heaven and earth, steeped in legends, the land of my ancestors. I almost enthralling travellers and explorers who undertook the most gruelling journeys to discover for envy those of you who have not themselves this exotic civilisation. Nowadays, yet been to China as the surprises travelling is easier but the allure of China remains and pleasures of my country are the same. We at China Holidays have the in-depth understanding, knowledge and passion needed still yours to discover, whilst for to create some of the best journeys by bringing those of you who have already been, together authentic cultural experiences and there are still so many more riches imaginative itineraries, combined with superb service and financial security. to savour – the rural charms of the minority villages in the west, sacred On the following pages you will find details of our new and exciting range of China Holidays, ranging mountains inhabited by dragons and from classic itineraries to in-depth regional journeys gods, nomadic life on the grasslands and themed holidays, which mix the ever-popular of Tibet and Inner Mongolia, along sights with the unusual. -

Sichuan, China

SICHUAN, CHINA May 23rd – June 11th 2004 by Fredrik Ellin, Erik Landgren and Peter Schmidt Below Balan Shan Pass, Wolong Introduction The idea for this trip was conceived after the three of us having consumed a few beers too many at a party in February. Since all of us were able to get time of work and we still thought it was a good idea a couple of weeks later, we soon started to make the arrangements. Firethroats and Rufous-headed Robins arrive to their breeding grounds fairly late in the season. Mainly for this reason, we decided to go in the end of May, even though we knew that by this time most migrants had already passed by. Initially, our intention was to visit also the Tibetan plateau on the way to Jiuzhaigou, but well in Sichuan, we soon realized that we would risk spending to much of our limited time on the roads and finally choose to stay more days in Wolong and in Jiuzhaigou. Although any attempt to communicate with people is hampered by the language barrier, we found most of the Chinese to be very friendly and helpful. The infamous crowds reported by others on Emei Shan were not a big problem and in Jiuzhaigou very few of the tourists leave the paved roads and boardwalks. Although all places visited offered some very impressive scenery, all of us thought that the visit to Wolong and Balan Shan was the nicest experience. Not only because this was the most accessible and less crowded place, but also because the alpine meadows and forests were quite extraordinary. -

Jiuzhaigou Valley Scenic & Historic Interest Area China

JIUZHAIGOU VALLEY SCENIC & HISTORIC INTEREST AREA CHINA The Jiuzhaigou valley extends over 72,000 hectares of northern Sichuan. The surrounding peaks rise more than 2,400m to 4,560m clothed in a series of forest ecosystems stratified by elevation. Its superb landscapes are particularly interesting for their series of narrow conic karst land forms and spectacular waterfalls and lakes. Some 140 bird species are found in the valley, as well as a number of endangered plant and animal species, including the giant panda and the Sichuan takin. There are Tibetan villages in the buffer zone. COUNTRY China NAME Jiuzhaigou Valley Scenic and Historic Interest Area NATURAL WORLD HERITAGE SITE 1992: Inscribed on the World Heritage List under Natural Criterion vii. STATEMENT OF OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE [pending] INTERNATIONAL DESIGNATION 1997: Jiuzhaigou Valley recognised as a Biosphere Reserve in the UNESCO Man and Biosphere Programme (106,090 ha). IUCN MANAGEMENT CATEGORY III Natural Monument BIOGEOGRAPHICAL PROVINCE Sichuan Highlands (2.39.12) GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION In northern Sichuan Province, west-central China, in the southern Min Shan Mountains some 270 km north of Chengdu. It includes the catchments of three streams which join the Zharu river to form the Jiuzhaigou river. Located between 32° 54' to 33°19'N and 103° 46' to 104° 04'E. DATES AND HISTORY OF ESTABLISHMENT 1978: Part of the area protected as a Nature Reserve. It had been almost unknown and undisturbed before 1975-79 when it was heavily logged, prompting state concern to protect the site; 1982: The site proposed as an area of Scenic Beauty and Historic Interest by the State Council of the People’s Republic of China; 1984: An Administration Bureau for the site was established; 1987: An overall plan for the site with regulations drafted and approved. -

5 Days Chengdu Mount Siguniang Overland Tour

[email protected] +86-28-85593923 5 days Chengdu Mount Siguniang overland tour https://windhorsetour.com/kham-tour/chengdu-danba-mount-siguniang-tour Chengdu Danba Rilong Mount Siguniang Valleys Chengdu Travel far from the city's crowds and into the unspoiled wilderness of Mount Siguniang on this 5 day photography lovers tour. Relax yourself in the Sichuan blue sky with ominous clouds, snow cover peaks and the sound of rushing waterfalls. Type Private Duration 5 days Trip code WS-502 Price From A$ 852 per person Itinerary The Mt. Siguniangshan ( Four-girl mountain) Scenic Area is an unspoiled wilderness park well-known throughout China, located in western Sichuan Province, near the town of Rilong in Aba. It includes one mountain - Mt. Siguniangshan, and three valleys -Shuangqiao Valley, Changping Valley, and Haizi Valley. The blue sky, clouds and mist, snow peaks, ancient cypress forests, rushing waterfalls, alpine meadows and local Tibetan and Qiang folk custom make this area like a fairyland. Day 01 : Chengdu / Danba Depart Chengdu in the early morning, drive to Danba (altitude 1,800m) by using the new tunnel at Balang mountain, it shortens the driving time to 6 hours. Danba, a county where you may see different Tibetan people and also their unique Danba ancient block towers. You will spend the night in Zhonglu village via a bumpy mountain road. You will explore Zhonglu village, crops fields and wait for the sunset. Overnight at Zhonglu local guest house. B=breakfast Day 02 : Sightseeing at Danba / Rilong (B) Enjoy the sunrise at Danba Zhonglu village if the weather permits, then head to visit the unique Danba Ancient block towers in Suopo, the grand and high one thousand years tower groups, the Dadu river valley, feeling and taste the folks and customs of Jiarong branch Tibet people. -

Heritage, Identity and Sense of Place in Sichuan Province After the 12 May Earthquake in China

Heritage, Identity and Sense of Place in Sichuan Province after the 12 May Earthquake in China by Xuejuan Zhang Thesis submitted as part of the final examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Royal Holloway College, University of London Declaration I, Xuejuan Zhang, declare that this thesis and the work presented in it are my own and that it has been produced by me as the result of my own original research. Signed: _________________________________ Date:__________________________________ 2 Abstract At 14.28 on 12 May 2008, a massive earthquake measuring 8.0 on the Richter scale struck Wenchuan County in Sichuan Province. Causing widespread destruction, it was considered to be the most severe earthquake in China’s history, and indeed one of the worst in the world. Drawing on the results of an ethnographic study carried out in the disaster areas between 2009 and 2013, this research explores the impact of the earthquake on cultural heritage, popular memory, memorialisation and tourism in Sichuan. Critically examining the complex, overlapping relationships between heritage, identity and sense of place in post-disaster Sichuan, I argue that historical sites that come to mark tragic events are not simply commemorative or historically important because a disastrous event has occurred, but that they are instead places which are continuously negotiated, constructed and reconstructed into places of meaning through on-going human action. While traditional interpretation of these sites are usually viewed as static ones, they are actually dynamic sites that both generate and are informed by official, popular and individual memory through acts of localised and non-localised place production and consumption. -

Notes on the Range and Ecology of Sichuan Treecreeper Certhia Tianquanensis

Forktail 20 (2004) SHORT NOTES 141 Notes on the range and ecology of Sichuan Treecreeper Certhia tianquanensis FRANK E. RHEINDT On the basis of museum specimens from two sites in long tail, extremely short bill and the diagnostic central Sichuan, Li (1995) described a new taxon of plumage coloration on the underparts (grading from treecreeper (tianquanensis) as a subspecies of the widely brown on the undertail-coverts to light white on the ranging Eurasian Treecreeper Certhia familiaris. chin). The bird was observed for several minutes and However, this description went largely unnoticed even the area was revisited on the following day, when by Chinese ornithologists. A few years later, during an presumably the same individual was seen at the same avifaunal survey of the Wawu Shan plateau in Sichuan, site (even on the same tree). Again, the bird called at Martens et al.(2002, 2003) found a distinct long intervals, possibly because of the late date, but I treecreeper with an unfamiliar vocalisation, which they managed to make a tape-recording (Fig. 1). could not immediately identify. After recourse to On 6 July 2003, during an ascent from the research museum specimens, they realised that what they had station of Wuyipeng in Wolong Biosphere Reserve found was Li’s (1995) tianquanensis, although they had (central Sichuan; 31o03’N 103o08’E), I had another found it occurring alongside Eurasian Treecreeper on unexpected encounter with a singing individual in a Wawu Shan. Morphologically and vocally, the new large stand of giant fir trees at c.2,800 m.The bird was taxon seemed to more closely resemble the Brown- seen singing, and the same site was revisited two days throated Treecreeper C.