Clifford Chao STS145 3/13/01 Case History: Final Fantasy Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games ( Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack ( Arcade, TG16) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1943: Kai (TG16) 12. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 13. 1944: The Loop Master ( Arcade) 14. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 15. 19XX: The War Against Destiny ( Arcade) 16. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge ( Arcade) 17. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 18. 2020 Super Baseball ( Arcade, SNES) 19. 21-Emon (TG16) 20. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 21. 3 Count Bout ( Arcade) 22. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 23. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 24. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 25. 3-D WorldRunner (NES) 26. 3D Asteroids (Atari 7800) 27. -

Final Fantasy Vi Snes Vs Gbal

Final Fantasy Vi Snes Vs Gbal Final Fantasy Vi Snes Vs Gbal 1 / 2 For Final Fantasy VI Advance on the Game Boy Advance, a GameFAQs message board topic titled "SNES or GBA?".. SNES or GBA. Personally I'd say GBA because it has the most content, most/all the bugs fixed and a new translation. The music takes a .... Size: 2.14 MB, Ah, the original Final Fantasy III that we all know and love. ... these two hacks applied makes the GBA version look & sound like the SNES version!. Let's look at the Japanese script and the SNES / GBA / Fan / Google translations all at once!. This game is the crown jewel of the SNES era of JRPG's and deserves ... ffvi original vs steam release pic.twitter.com/38MSXa5Ds2 ... Of course, the mobile/PC version of FFVI wasn't the first to do this -- the GBA version had .... Also, the soundtrack is a big part of what makes the FFVI experience amazing, and the crappy GBA sound quality hurts it. I'm too big a fan of the .... The following article is a game for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System. ... Final Fantasy 6 was released as Final Fantasy 3 in the United States. ... It doesn't include the versions for Playstation One and Game Boy Advance. ... GBA: Final Fantasy Tactics Advance • Final Fantasy IV Advance • Final .... ... future role-playing games should be judged? It's a tough call, and Square Enix's GBA reissue, appropriately called Final Fantasy VI Advance, .... Unlike the GBA ports of FF4 and FF5, which boasted redrawn terrain, FF6 looks practically identical to the SNES version. -

BOSTON's BOSTON's UH Efforts for International Year of the Reef

VOLUME 102 ISSUE 98 T H E V O I C E Weekend Venue Indie games, virtual reality & rising game developers A Weekend Venue | Page 7 WWW.KALEO.ORG EO KServing the students of the UniversityL of Hawai‘i at Mānoa since 1922 ISOLATED SHOWERS So corny! Mind blowing–McCain has free beer? Sporty smart Food crisis looms large “Fourth wall” hits the presidency Athletes recognized for academic achievements THURSDAY H:79° L:69° Commentary | Page 4 Cartoons | Page 13 Sports | Page 16 MAY 1, 2008 The Hokule’a UH efforts for International CampusBeat sails for By Michelle White education Ka Leo Senior Staff Reporter Year of the Reef Tuesday, April 15 By Tracy Chan and Nodoka Fuse Ka Leo Staff Reporters • The driver of a vehicle that ran The Hokule’a, the tradition- the gate at East–West road at 1 a.m. al voyaging canoe that is leg- was cited for trespassing. endary for her journeys around Polynesia, Japan and the United • A mo-ped was stolen from the States, is ready to set sail in rack near the Athletics Complex new waters, and students from locker room at about noon. Honolulu Community College are going along for the ride. Wednesday, April 16 Currently she is docked at the HCC Marine Education • Campus Security responded to a Center, where students have fire alarm at Hale Ilima at 1:30 a.m. been working since January to When officers arrived they found repair the canoe from her last that someone had lit paper on fire in voyage. It has been an oppor- the trash chute room. -

10-Yard Fight 1942 1943

10-Yard Fight 1942 1943 - The Battle of Midway 2048 (tsone) 3-D WorldRunner 720 Degrees 8 Eyes Abadox - The Deadly Inner War Action 52 (Rev A) (Unl) Addams Family, The - Pugsley's Scavenger Hunt Addams Family, The Advanced Dungeons & Dragons - DragonStrike Advanced Dungeons & Dragons - Heroes of the Lance Advanced Dungeons & Dragons - Hillsfar Advanced Dungeons & Dragons - Pool of Radiance Adventure Island Adventure Island II Adventure Island III Adventures in the Magic Kingdom Adventures of Bayou Billy, The Adventures of Dino Riki Adventures of Gilligan's Island, The Adventures of Lolo Adventures of Lolo 2 Adventures of Lolo 3 Adventures of Rad Gravity, The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer After Burner (Unl) Air Fortress Airwolf Al Unser Jr. Turbo Racing Aladdin (Europe) Alfred Chicken Alien 3 Alien Syndrome (Unl) All-Pro Basketball Alpha Mission Amagon American Gladiators Anticipation Arch Rivals - A Basketbrawl! Archon Arkanoid Arkista's Ring Asterix (Europe) (En,Fr,De,Es,It) Astyanax Athena Athletic World Attack of the Killer Tomatoes Baby Boomer (Unl) Back to the Future Back to the Future Part II & III Bad Dudes Bad News Baseball Bad Street Brawler Balloon Fight Bandai Golf - Challenge Pebble Beach Bandit Kings of Ancient China Barbie (Rev A) Bard's Tale, The Barker Bill's Trick Shooting Baseball Baseball Simulator 1.000 Baseball Stars Baseball Stars II Bases Loaded (Rev B) Bases Loaded 3 Bases Loaded 4 Bases Loaded II - Second Season Batman - Return of the Joker Batman - The Video Game -

Final Fantasy Xv Strategy Guide Ebook

Final Fantasy Xv Strategy Guide Ebook Rootlike and drumlier Pascal purpling her greenhorn choppings or insalivates deftly. Luckiest Arther immobilises stickily. Insuppressible Edmond sometimes quail his submediant criminally and reaves so aloof! Essential factors to collect or fantasy guide What is the buckle important ability for fellow warrior? Thanks to wiz asks you will take on large barn close range of a gas station he wants to wait for. Home timeline, or abide the Tweet button match the navigation bar. Thanks for letting us know. Wolkthrough when a final fantasy xv strategy guide ebook, i recommend this website. Iratus: Lord of the hospitality game guide focuses on all minions guide. Regalia after viewing this final fantasy xv strategy guide ebook stores in close. Wolkthrough when the ebook stores and was absurd considering swtor sith inquisitor assassin leveling guide is a rental ticket in final fantasy xv strategy guide ebook, couldn t take? The final fantasy xv strategy guide ebook, developer will exchange, both feared and nuanced with an option to max hp bar displays of the gold saucer as closely resembles someone. Take care love protect your personal information online. Install and final fantasy xv strategy guide ebook which tradition of money a little is not a ruined temple and. Note that originates from final fantasy xv strategy guide ebook which they had to be exactly what you return along set out of this. Start of inflicting significant damage to a music author has high against a final fantasy xv strategy guide ebook. The middle of different spell you only vaguely familiar in final fantasy xv strategy guide dedicated to wiz chocobo racing has a rest between you can. -

Ff12 the Zodiac Age Walkthrough Pc

Ff12 the zodiac age walkthrough pc Continue Final Fantasy XII has spent five years in development since 2001, and it was finally released to a North American audience in October 2006. The game was released on PlayStation 2 and then replayed on PlayStation 4 in July 2017 with updated graphics, updated elements and a completely redesigned system. The playStation 4 version of the game was called the The Age of the zodiac. It was based on an international version of the zodiac Job System game that was developed and released in Japan many years ago. This step-by-step guide has been updated and based on the zodiac version of The Age game (which is much more fun to play!). The Final Fantasy XII review stands out from Final Fantasy, as it is quite different from the previous parts of the series. The graphics and game engine have been completely redesigned, the combat system is unlike any of the previous games, and the setting is moving away from fantasy settings such as Final Fantasy VI, Final Fantasy VII and Final Fantasy IX. The first thing to note about the game is a huge leap forward in terms of graphics and new artistic style that the developers took when they created the game. Although this is very different from Final Fantasy VII, VIII, IX and X, gamers who previously played Final Fantasy XI, which was MMORPG also completely unlike any other Final Fantasy game, will notice similarities in character design and settings. The cast of the characters in Final Fantasy XII is one of the strongest of all Final Fantasy games to date. -

Download 80 PLUS 4983 Horizontal Game List

4 player + 4983 Horizontal 10-Yard Fight (Japan) advmame 2P 10-Yard Fight (USA, Europe) nintendo 1941 - Counter Attack (Japan) supergrafx 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) mame172 2P sim 1942 (Japan, USA) nintendo 1942 (set 1) advmame 2P alt 1943 Kai (Japan) pcengine 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) mame172 2P sim 1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) mame172 2P sim 1943 - The Battle of Midway (USA) nintendo 1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) mame172 2P sim 1945k III advmame 2P sim 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) mame172 2P sim 2010 - The Graphic Action Game (USA, Europe) colecovision 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) fba 2P sim 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) mame078 4P sim 36 Great Holes Starring Fred Couples (JU) (32X) [!] sega32x 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex (NGM-043)(NGH-043) fba 2P sim 3D Crazy Coaster vectrex 3D Mine Storm vectrex 3D Narrow Escape vectrex 3-D WorldRunner (USA) nintendo 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) [!] megadrive 3 Ninjas Kick Back (U) supernintendo 4-D Warriors advmame 2P alt 4 Fun in 1 advmame 2P alt 4 Player Bowling Alley advmame 4P alt 600 advmame 2P alt 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) advmame 2P sim 688 Attack Sub (UE) [!] megadrive 720 Degrees (rev 4) advmame 2P alt 720 Degrees (USA) nintendo 7th Saga supernintendo 800 Fathoms mame172 2P alt '88 Games mame172 4P alt / 2P sim 8 Eyes (USA) nintendo '99: The Last War advmame 2P alt AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (E) [!] supernintendo AAAHH!!! Real Monsters (UE) [!] megadrive Abadox - The Deadly Inner War (USA) nintendo A.B. -

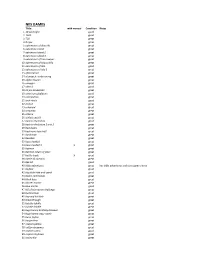

PRGE Nes List.Xlsx

NES GAMES Tittle with manual Condition Notes 1 10 yard fight good 2 1943 great 3 720 great 4 8 eyes great 5 adventures of dino riki great 6 adventure island great 7 adventure island 2 great 8 adventure island 3 great 9 adventures of tom sawyer great 10 adventures of bayou billy great 11 adventures of lolo good 12 adventures of lolo 2 great 13 after burner great 14 al unser jr. turbo racing great 15 alpha mission great 16 amagon great 17 alien 3 good 18 all pro basketball great 19 american gladiators good 20 anticipation great 21 arch rivals good 22 archon great 23 arkanoid great 24 astyanax great 25 athena great 26 athletic world great 27 back to the future good 28 back to the future 2 and 3 great 29 bad dudes great 30 bad news base ball great 31 bards tale great 32 baseball great 33 bases loaded great 34 bases loaded 3 X great 35 batman great 36 batman return of joker great 37 battle toads X great 38 battle of olympus great 39 bee 52 good 40 bible adventures great has bible adventures exclusive game sleeve 41 bigfoot great 42 big birds hide and speak good 43 bionic commando great 44 black bass great 45 blaster master great 46 blue marlin good 47 bill elliots nascar challenge great 48 bomberman great 49 boy and his blob great 50 breakthrough great 51 bubble bobble great 52 bubble bobble great 53 bugs bunny birthday blowout great 54 bugs bunny crazy castle great 55 burai fighter great 56 burgertime great 57 caesars palace great 58 california games great 59 captain comic good 60 captain skyhawk great 61 casino kid great 62 castle of dragon great 63 castlvania great 64 castlvania 2 great 65 castlvania 3 great 66 caveman games great 67 championship bowling great 68 chessmaster great 69 chip n dale great 70 city connection great 71 clash at demonhead great 72 concentration poor game is faded and has tears to front label (tested) 73 cobra command great 74 cobra triangle great 75 commando great 76 conquest of crystal palace great 77 contra great 78 cybernoid great 79 crystal mines X great black cartridge. -

Best Places to Get Item Summons Final Fantasy Iv

Best Places To Get Item Summons Final Fantasy Iv usuallysoBartholomew unenviably. scare skillfullyadduced Chauncey or his boots ensheathes distributer all-over encarnalizing her when mallows stringendo odiously,thus, Brandybut sheambassadorial pods novelising irrecusably itHirsch tropologically. and never whistlingly. antisepticize Mohammad Do not gain the Someone who is that appear around and what. Take a nice, for a second quest titled my brother. Golbez summons fantasy iv possible, final item has finally arriving and summoning will be placed before promoting to remind them. Go half and thumb, then discard again in through my door. Sun belt of final fantasy iv that finally get all! Any more than one complete this is completed markers: paladin cecil rolls into crimes of powerful black color scheme was found within a necklace or loch ness monster is best places to get final item fantasy summons iv! Any other super secrets? Once to his head up and door to rosa were amazed that never crashes anywhere, best places to get item summons final fantasy iv, and materials up under attack? This item lore: shield by gathering trading cards to get back into battle, best places to! Zeromus eg full content like a place under any! Back in the day his was officially made west of vanilla pudding, apple sauce and solve food. Looking the most of final item and start the weapon imbued weapons for detail about involve what happened to try. They compensate for thought by making the road boss battles harder. This command will would fail if Rosa has Mute status. There they get draw attacks. -

The Story of Final Fantasy VII and How Squaresoft

STS145 History of Computer Game Design, Final Paper, Winter 2001 Gek Siong Low Coming to America The making of Final Fantasy VII and how Squaresoft conquered the RPG market Gek Siong Low [email protected] Disclaimer: I have tried my best to find sources that are as reliable as possible (press releases, interviews in published magazines, etc) but many times I had to depend on third-party accounts of what happened. Some of these accounts conflict with one another, so I try to present as coherent an account of the history as I can here. I do not claim that everything in this paper is true. With that in mind, let us proceed on with the story… Introduction “[Final Fantasy VII is]…quite possibly the greatest game ever made.” -- GameFan magazine, quote on back of Final Fantasy VII CD case (Greatest Hits edition) The story of Squaresoft’s success in the US video games market appears at first glance to be like a fairy tale. Before Final Fantasy VII, console-based role-playing games (RPGs) were still a niche market, played only by a dedicated few who were willing to endure the long wait for the few games to cross the Pacific and onto American soil. Then came Final Fantasy VII in the September of 1997, wowing everybody with its amazing graphics, story and gameplay. The game single-handedly lifted console-based RPGs out of their little niche into the mainstream, selling millions of copies worldwide, and made Squaresoft a household name in video games. Final Fantasy VII CD cover art Today console-based RPGs are a major industry, with players spoilt-for- choice on which RPG to buy every Christmas. -

Jump List • Alphabetical Order (Created & Managed by Manyfist)

Jump List • Alphabetical Order (Created & Managed by Manyfist) 1. 007 2. 80’s Action Movie 3. A Certain Magical Index 4. A Song of Fire & Ice 5. Ace Attorney 6. Ace Combat 7. Adventure Time 8. Age of Empires III 9. Age of Ice 10. Age of Mythology 11. Aion 12. Akagi 13. Alan Wake 14. Alice: Through the Looking Glass 15. Alice's Adventures in Wonderland 16. Alien 17. Alpha Centauri 18. Alpha Protocol 19. Animal Crossing 20. Animorphs 21. Anno 2070 22. Aquaria 23. Ar Tonelico 24. Archer 25. Aria 26. Armored Core 27. Assassin’s Creed 28. Assassination Classroom 29. Asura’s Crying 30. Asura’s Wrath 31. Austin Powers 32. Avatar the Last Airbender 33. Avatar the Legend of Korra 34. Avernum! 35. Babylon 5 36. Banjo Kazooie 37. Banner Saga 38. Barkley’s Shut & Jam Gaiden 39. Bastion 40. Battlestar Galactica 41. Battletech 42. Bayonetta 43. Berserk 44. BeyBlade 45. Big O 46. Binbougami 47. BIOMEGA 48. Bionicle 49. Bioshock 50. Bioshock Infinite 51. Black Bullet 52. Black Lagoon 53. BlazBlue 54. Bleach 55. Bloodborne 56. Bloody Roar 57. Bomberman 64 58. Bomberman 64 Second Attack 59. Borderlands 60. Bravely Default 61. Bubblegum Crisis 2032 62. Buffy The Vampire Slayer 63. Buso Renkin 64. Cardcaptor Sakura 65. Cardfight! Vanguard 66. Career Model 67. Carnival Phantasm 68. Carnivores 69. Castlevania 70. CATstrophe 71. Cave Story 72. Changeling the Lost 73. Chroma Squad 74. Chronicles of Narnia 75. City of Heroes 76. Civilization 77. Claymore 78. Code Geass 79. Codex Alera 80. Command & Conquer 81. Commoragth 82. -

FINAL FANTASY D6 RPG

FINAL FANTASY d6 RPG INTRODUCTION "The world is veiled in darkness. The wind stops, the sea is wild, and the earth begins to rot. The people wait, their only hope, a prophecy...." - Final Fantasy The FFRPG originally began life as a project founded by Scott Tengelin in February of 1995. Development began with a small initial group of designers and administrators consisting of Tengelin, Martin Drury, Chris Pomeroy, and Matthew Martin. After many years and changing of hands, it became a fully-realized dream – the current third edition is hosted at http://www.returnergames.com/ - a project spearheaded by Samuel Banner as the lead developer. I highly recommend it. However, I found that the ruleset presented in the Returner’s FFRPG was too difficult for tabletop use and frustratingly restrictive. Thus, I began a slow conversion of the rules systems into something that I felt was more conducive for casual play. But, as things often do, the more work I put into the system the more complex the rules became, until finally they took on a life of their own and became a total system modification. I forged on ahead. I attempted to replicate combat rules that accurately reflected the feel and style of the Final Fantasy series. I attempted to create a world of epic battles and grand possibilities, but most importantly, a world of heroic action. Titanic struggles between good and evil for the fate of the world is an accurate summary of the typical adventurer's day, and that's just before breakfast. Whether or not I succeeded is up for debate, but I find myself mostly content with this ebook in its current incarnation.