Disability in Time and Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

900 History, Geography, and Auxiliary Disciplines

900 900 History, geography, and auxiliary disciplines Class here social situations and conditions; general political history; military, diplomatic, political, economic, social, welfare aspects of specific wars Class interdisciplinary works on ancient world, on specific continents, countries, localities in 930–990. Class history and geographic treatment of a specific subject with the subject, plus notation 09 from Table 1, e.g., history and geographic treatment of natural sciences 509, of economic situations and conditions 330.9, of purely political situations and conditions 320.9, history of military science 355.009 See also 303.49 for future history (projected events other than travel) See Manual at 900 SUMMARY 900.1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901–909 Standard subdivisions of history, collected accounts of events, world history 910 Geography and travel 920 Biography, genealogy, insignia 930 History of ancient world to ca. 499 940 History of Europe 950 History of Asia 960 History of Africa 970 History of North America 980 History of South America 990 History of Australasia, Pacific Ocean islands, Atlantic Ocean islands, Arctic islands, Antarctica, extraterrestrial worlds .1–.9 Standard subdivisions of history and geography 901 Philosophy and theory of history 902 Miscellany of history .2 Illustrations, models, miniatures Do not use for maps, plans, diagrams; class in 911 903 Dictionaries, encyclopedias, concordances of history 901 904 Dewey Decimal Classification 904 904 Collected accounts of events Including events of natural origin; events induced by human activity Class here adventure Class collections limited to a specific period, collections limited to a specific area or region but not limited by continent, country, locality in 909; class travel in 910; class collections limited to a specific continent, country, locality in 930–990. -

Guitar Center Partners with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, and Carlos

Guitar Center Partners with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, and Carlos Santana on New 2019 Crossroads Guitar Collection Featuring Five Limited-Edition Signature and Replica Guitars Exclusive Guitar Collection Developed in Partnership with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, Carlos Santana, Fender®, Gibson, Martin and PRS Guitars to Benefit Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Centre Antigua Limited Quantities of the Crossroads Guitar Collection On-Sale in North America Exclusively at Guitar Center Starting August 20 Westlake Village, CA (August 21, 2019) – Guitar Center, the world’s largest musical instrument retailer, in partnership with Eric Clapton, proudly announces the launch of the 2019 Crossroads Guitar Collection. This collection includes five limited-edition meticulously crafted recreations and signature guitars – three from Eric Clapton’s legendary career and one apiece from fellow guitarists John Mayer and Carlos Santana. These guitars will be sold in North America exclusively at Guitar Center locations and online via GuitarCenter.com beginning August 20. The collection launch coincides with the 2019 Crossroads Guitar Festival in Dallas, TX, taking place Friday, September 20, and Saturday, September 21. Guitar Center is a key sponsor of the event and will have a strong presence on-site, including a Guitar Center Village where the limited-edition guitars will be displayed. All guitars in the one-of-a-kind collection were developed by Guitar Center in partnership with Eric Clapton, John Mayer, Carlos Santana, Fender, Gibson, Martin and PRS Guitars, drawing inspiration from the guitars used by Clapton, Mayer and Santana at pivotal points throughout their iconic careers. The collection includes the following models: Fender Custom Shop Eric Clapton Blind Faith Telecaster built by Master Builder Todd Krause; Gibson Custom Eric Clapton 1964 Firebird 1; Martin 000-42EC Crossroads Ziricote; Martin 00-42SC John Mayer Crossroads; and PRS Private Stock Carlos Santana Crossroads. -

The Dr. Alister Mackenzie Chronology (2018)

The Dr. Alister MacKenzie Chronology th The 20 Revision October 2018 The MacKenzie Chronology Project The Project In the late 1990’s Nick Leefe and Bob Beck launched an effort to document the physical presence and movements of the great architect Dr. Alister MacKenzie. That effort sparked club secretaries, historians, architects, professional writers, enthusiasts – in short, a global community of MacKenzie admirers – to share their knowledge. This, the 20th Revision of “The Dr. Alister MacKenzie Chronology,” is the latest product of that collective and continuing generosity, and once again expands upon the previous revision. Why are MacKenzie’s whereabouts important? A timeline establishes a foundation of fact. Upon this foundation researchers can build their narratives of history. Without this fact base, large gaps in time appear, and speculation is the all too-common and unfortunate result - the quality of scholarship is impoverished. The ramifications can be significant - original design features and perhaps entire courses disappear or suffer disfiguration, writings are misunderstood or misinterpreted, attributions are missed or made improperly. As readers, as golfers, and as caretakers of the game of golf, we suffer. Dr. MacKenzieAdvertisement photographed for on The American Golf Course ConstructionCover of a printed version of one of MacKenzieRobert Hunter,and Hunter’s S.H. Woodruff, new 8th unknown, and Dr. Alister board the S.S.Company Berengaria showing en-route the 3rd green at MacKenzie & Hunter’sMacKenzie’s many lectures on the subject greenMacKenzie at Claremont at proposed Country Dana Club Point in Golf Course, California to England,Cypress March Point 9, 1926 Club on the Monterey Peninsula, Californiaof Architecture and Greenkeeping. -

Wheelchair Basketball Athletes: Motives for Participation

WHEELCHAIR BASKETBALL ATHLETES: MOTIVES FOR PARTICIPATION by Ashley Bohnert July 2016 Director of Thesis: Thomas K. Skalko, Ph.D., LRT/CTRS Major Department: Department of Recreation and Leisure Studies The purpose of this study was to examine the differences between demographic and individual player characteristics (i.e., gender, wheelchair basketball division, and individual athlete classification) and motives for involvement in adult wheelchair basketball athletes. Ninety-six wheelchair basketball players from teams in the National Wheelchair Basketball Association (NWBA), ages 18-67 years old, participated in the study. Participants completed a Qualtrics survey that collected demographic information and included the Motives for Physical Activities Measure-Revised (MPAM-R). The MPAM-R measures five different motives for participation in athletes: interest/enjoyment, competence, appearance, fitness, and social motivation. Results demonstrated a significant difference [F (4,82) = 3.118, p=.020] between the Women’s Division and the Championship Division on the competence scale (MD=0.74, p=.041), as well as a significant difference [F (4,80) = 3.665, p=.009] between the Men’s Collegiate Division and Division III on the fitness scale (MD= 0.96, p=.047). The results of this study offer some insight into motivating wheelchair basketball players and differences among various divisions in the NWBA. The results from this study may benefit recreational therapy professionals, wheelchair basketball athletes, their coaches, and professionals involved -

The Cultural and Ideological Significance of Representations of Boudica During the Reigns of Elizabeth I and James I

EXETER UNIVERSITY AND UNIVERSITÉ D’ORLÉANS The Cultural and Ideological Significance Of Representations of Boudica During the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I. Submitted by Samantha FRENEE-HUTCHINS to the universities of Exeter and Orléans as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, June 2009. This thesis is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ..................................... (signature) 2 Abstract in English: This study follows the trail of Boudica from her rediscovery in Classical texts by the humanist scholars of the fifteenth century to her didactic and nationalist representations by Italian, English, Welsh and Scottish historians such as Polydore Virgil, Hector Boece, Humphrey Llwyd, Raphael Holinshed, John Stow, William Camden, John Speed and Edmund Bolton. In the literary domain her story was appropriated under Elizabeth I and James I by poets and playwrights who included James Aske, Edmund Spenser, Ben Jonson, William Shakespeare, A. Gent and John Fletcher. As a political, religious and military figure in the middle of the first century AD this Celtic and regional queen of Norfolk is placed at the beginning of British history. In a gesture of revenge and despair she had united a great number of British tribes and opposed the Roman Empire in a tragic effort to obtain liberty for her family and her people. -

The New York City Draft Riots of 1863

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1974 The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863 Adrian Cook Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Cook, Adrian, "The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863" (1974). United States History. 56. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/56 THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS This page intentionally left blank THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS TheNew York City Draft Riots of 1863 ADRIAN COOK THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY ISBN: 978-0-8131-5182-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-80463 Copyright© 1974 by The University Press of Kentucky A statewide cooperative scholarly publishing agency serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky State College, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506 To My Mother This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix -

Education, Instruction and Apprenticeship at the London Foundling Hospital C.1741 - 1800

Fashioning the Foundlings – Education, Instruction and Apprenticeship at the London Foundling Hospital c.1741 - 1800 Janette Bright MRes in Historical Research University of London September 2017 Institute of Historical Research School of Advanced Study Index Chapter One – Introduction Pages 2 - 14 Chapter Two – Aims and objectives Pages 14 - 23 Chapter Three - Educating the Foundlings: Pages 24 - 55 schooling and vocational instruction Chapter Four – Apprenticeship Pages 56 - 78 Chapter Five – Effectiveness and experience: Pages 79 - 97 assessing the outcomes of education and apprenticeship Chapter Six – Final conclusions Pages 98 - 103 Appendix – Prayers for the use of the foundlings Pages 104 - 105 Bibliography Pages 106 - 112 3 Chapter one: introduction Chapter One: Introduction Despite the prominence of the word 'education' in the official title of the London Foundling Hospital, that is 'The Hospital for the Maintenance and Education of Exposed and Deserted Young Children', it is surprising to discover this is an under researched aspect of its history. Whilst researchers have written about this topic in a general sense, gaps and deficiencies in the literature still exist. By focusing on this single component of the Hospital’s objectives, and combining primary sources in new ways, this study aims to address these shortcomings. In doing so, the thesis provides a detailed assessment of, first, the purpose and form of educational practice at the Hospital and, second, the outcomes of education as witnessed in the apprenticeship programme in which older foundlings participated. In both cases, consideration is given to key shifts in education and apprenticeship practices, and to the institutional and contextual forces that prompted these developments over the course of the eighteenth century. -

Inclusion London Response Labour Party Mental Health Policy

Inclusion London submission to the Labour Party’s mental health policy consultation Consultation paper: http://www.yourbritain.org.uk/agenda-2020/commissions/health June 2016 For more information contact: Henrietta Doyle, 07703 715091 [email protected] Inclusion London 1 1. Introduction Inclusion London Inclusion London is a London-wide user-led organisation which promotes equality for London’s Deaf and Disabled people and provides capacity- building support for over 90 Deaf and Disabled people’s organisations in London and through these organisations our reach extends to over 70,000 Disabled Londoners. Inclusion London is one of the leading organisations in the Reclaiming Our Futures Alliance, a national network of grassroots Deaf and Disabled People’s Organisations and campaigns across England. Disabled people In 2012/13 there were approximately 12.2 million Disabled adults and children in the UK, a rise from 10.8 million in 2002/03. The estimated percentage of the population who were disabled remained relatively constant over time at around 19 per cent.1 There are approximately 1.2 million Disabled people living in London.2 1 Family Resources survey United Kingdom 2012/13: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/325491/fa mily-resources-survey-statistics-2012-2013.pdf (page 61) 2https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/325491/fa mily-resources-survey-statistics-2012-2013.pdf (page 64) Inclusion London 2 2. Summary of recommendations Recommendation 1 - Inclusion London promotes the principle of ‘Nothing About us Without us’ and recommends that the Labour Party continues to consult with experts by experience, i.e. -

Vrije Universiteit Brussel Abandoned in Brussels, Delivered in Paris: Long-Distance Transports of Unwanted Children in the Eight

Vrije Universiteit Brussel Abandoned in Brussels, Delivered in Paris: Long-Distance Transports of Unwanted Children in the Eighteenth Century Winter, Anne Published in: Journal of Family History Publication date: 2010 Document Version: Accepted author manuscript Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Winter, A. (2010). Abandoned in Brussels, Delivered in Paris: Long-Distance Transports of Unwanted Children in the Eighteenth Century. Journal of Family History, 35(2), 232-248. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 Published in: Journal of Family History, 35 (2010), 3, 232-248. See the journal article for the final version. Abandoned in Brussels, delivered in Paris: Long-distance transports of unwanted children in the eighteenth century Anne Winter Abstract The study uses examinations and other documents produced in the course of a large-scale investigation undertaken by the central authorities of the Austrian Netherlands in the 1760s on the transportation of around thirty children from Brussels to the Parisian foundling house by a Brussels shoemaker and his wife. -

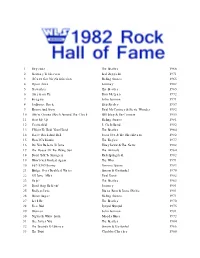

(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Open Ar

1 Hey Jude The Beatles 1968 2 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 3 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Open Arms Journey 1982 5 Yesterday The Beatles 1965 6 American Pie Don McLean 1972 7 Imagine John Lennon 1971 8 Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley 1957 9 Ebony And Ivory Paul McCartney & Stevie Wonder 1982 10 (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 11 Start Me Up Rolling Stones 1981 12 Centerfold J. Geils Band 1982 13 I Want To Hold Your Hand The Beatles 1964 14 I Love Rock And Roll Joan Jett & The Blackhearts 1982 15 Hotel California The Eagles 1977 16 Do You Believe In Love Huey Lewis & The News 1982 17 The House Of The Rising Sun The Animals 1964 18 Don't Talk To Strangers Rick Springfield 1982 19 Won't Get Fooled Again The Who 1971 20 867-5309/Jenny Tommy Tutone 1982 21 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel 1970 22 '65 Love Affair Paul Davis 1982 23 Help! The Beatles 1965 24 Don't Stop Believin' Journey 1981 25 Endless Love Diana Ross & Lionel Richie 1981 26 Brown Sugar Rolling Stones 1971 27 Let It Be The Beatles 1970 28 Free Bird Lynyrd Skynyrd 1975 29 Woman John Lennon 1981 30 Nights In White Satin Moody Blues 1972 31 She Loves You The Beatles 1964 32 The Sounds Of Silence Simon & Garfunkel 1966 33 The Twist Chubby Checker 1960 34 Jumpin' Jack Flash Rolling Stones 1968 35 Jessie's Girl Rick Springfield 1981 36 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 37 A Hard Day's Night The Beatles 1964 38 California Dreamin' The Mamas & The Papas 1966 39 Lola The Kinks 1970 40 Lights Journey 1978 41 Proud -

Development and Validation of the Deaf Athletic Coping Skills Inventory

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2007 Development and Validation of the Deaf Athletic Coping Skills Inventory Jason S. Grindstaff University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Grindstaff, Jason S., "Development and Validation of the Deaf Athletic Coping Skills Inventory. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Jason S. Grindstaff entitled "Development and Validation of the Deaf Athletic Coping Skills Inventory." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Sport Studies. Leslee A. Fisher, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Craig A. Wrisberg, John W. Lounsbury, Jeffrey E. Davis Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Jason S. Grindstaff entitled “Development and Validation of the Deaf Athletic Coping Skills Inventory.” I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Sport Studies. -

RIEVAULX ABBEY and ITS SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT, 1132-1300 Emilia

RIEVAULX ABBEY AND ITS SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT, 1132-1300 Emilia Maria JAMROZIAK Submitted in Accordance with the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History September 2001 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Dr Wendy Childs for her continuous help and encouragement at all stages of my research. I would also like to thank other faculty members in the School of History, in particular Professor David Palliser and Dr Graham Loud for their advice. My thanks go also to Dr Mary Swan and students of the Centre for Medieval Studies who welcomed me to the thriving community of medievalists. I would like to thank the librarians and archivists in the Brotherton Library Leeds, Bodleian Library Oxford, British Library in London and Public Record Office in Kew for their assistance. Many people outside the University of Leeds discussed several aspects of Rievaulx abbey's history with me and I would like to thank particularly Dr Janet Burton, Dr David Crouch, Professor Marsha Dutton, Professor Peter Fergusson, Dr Brian Golding, Professor Nancy Partner, Dr Benjamin Thompson and Dr David Postles as well as numerous participants of the conferences at Leeds, Canterbury, Glasgow, Nottingham and Kalamazoo, who offered their ideas and suggestions. I would like to thank my friends, Gina Hill who kindly helped me with questions about English language, Philip Shaw who helped me to draw the maps and Jacek Wallusch who helped me to create the graphs and tables.