The Nordic Model for Supporting Artists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Danish Museum Art Library: the Danish Museum of Decorative Art Library*

INSPEL 33(1999)4, pp. 229-235 A DANISH MUSEUM ART LIBRARY: THE DANISH MUSEUM OF DECORATIVE ART LIBRARY* By Anja Lollesgaard Denmark’s library system Most libraries in Denmark are public, or provide public access. The two main categories are the public, local municipal libraries, and the public governmental research libraries. Besides these, there is a group of special and private libraries. The public municipal libraries are financed by the municipal government. The research libraries are financed by their parent institution; in the case of the art libraries, that is, ultimately, the Ministry of Culture. Most libraries are part of the Danish library system, that is the official library network of municipal and governmental libraries, and they profit from and contribute to the library system as a whole. The Danish library system is founded on an extensive use of inter-library lending, deriving from the democratic principle that any citizen anywhere in the country can borrow any particular book through the local public library, free of charge, never mind where, or in which library the book is held. Some research libraries, the national main subject libraries, are obliged to cover a certain subject by acquiring the most important scholarly publications, for the benefit not only of its own users but also for the entire Danish library system. Danish art libraries Art libraries in Denmark mostly fall into one of two categories: art departments in public libraries, and research libraries attached to colleges, universities, and museums. Danish art museum libraries In general art museum libraries are research libraries. Primarily they serve the curatorial staff in their scholarly work of documenting artefacts and art historical * Paper presented at the Art Library Conference Moscow –St. -

Britain's Hype for British Hygge

Scandinavica Vol 57 No 2 2018 What the Hygge? Britain’s Hype for British Hygge Ellen Kythor UCL Abstract Since late 2016, some middle-class Brits have been wearing Nordic- patterned leg warmers and Hygge-branded headbands while practising yoga in candlelight and sipping ‘Hoogly’ tea. Publishers in London isolated hygge as an appealing topic for a glut of non-fiction books published in time for Christmas 2016. This article elucidates the origins of this British enthusiasm for consuming a particular aspect of ostensibly Danish culture. It is argued that British hype for hygge is an extension of the early twenty-first century’s Nordic Noir publishing and marketing craze, but additionally that the concept captured the imaginations of journalists, businesses, and consumers as a fitting label for activities and products of which a particular section of the culturally white-British middle-classes were already partaking. Keywords Hygge, United Kingdom, white culture, Nordic Noir, publishing, cultural studies 68 Scandinavica Vol 57 No 2 2018 A December 2015 print advertisement in The Guardian for Arrow Films’ The Bridge DVDs reads: ‘Gettin’ Hygge With It!’, undoubtedly a play on the phrase from 1990s pop music hit ‘Gettin’ Jiggy Wit It’ (HMV ad 2015). Arrow Films’ Marketing Director Jon Sadler perceived the marketing enthusiasm for hygge¹ that hit Britain a year later with slight envy: ‘we’ve been talking about hygge for several years, it’s not a new thing for us [...] it’s a surprise it’s so big all of a sudden’ (Sadler 2017). Arrow Films was a year too early in its attempt to use hygge as a marketing trope. -

New Nordic Cuisine Best Restaurant in the World Bocuse D'or

English // A culinary revolution highlighting local foods and combating uniform- ity has been enhancing the Taste of Denmark over the past decade. The perspec- tives of this trend are useful to everyone – in private households and catering kitchens alike. Nordic chefs use delicious tastes and environmental sustainability to combat unwholesome foods and obesity. www.denmarkspecial.dk At the same time, Danish designers continue to produce and develop furniture, tables and utensils which make any meal a holistic experience. Learn more about New Nordic Cuisine and be inspired by the ingredients, produce, restaurants and quality design for your dining experience. FOOD & DESIGN is a visual appetiser for what’s cooking in Denmark right now. Français // Une révolution culinaire axée sur les ingrédients locaux et opposée à une uniformisation a, ces 10 dernières années, remis au goût du jour les saveurs du Danemark. Cette évolution ouvre des perspectives à la disposition de tous – qu’il s’agisse de la cuisine privée ou de la cuisine à plus grande échelle. Les chefs nordiques mettent en avant les saveurs et l’environnement contre la mauvaise santé et le surpoids. Parallèlement, les designers danois ont maintenu et développé des meubles, tables et ustensiles qui font du repas une expérience d’ensemble agréable. Découvrez la nouvelle cuisine nordique et puisez l’inspiration pour vos repas dans les matières premières, les restaurants et le bon design. FOOD & DESIGN est une mise en bouche visuelle de ce qui se passe actuellement côté cuisine au Danemark. Food & Design is co-financed by: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, The Trade Council What’s cooking in Denmark? New Nordic Cuisine Bocuse d’Or Playing among the stars Issue #9 2011 denmark Printed in Denmark EUR 10.00 // USD 13.00 Best restaurant special NZD 17.50 // AUD 13.50 ISBN No. -

“To Establish a Free and Open Forum”: a Memoir of the Founding of the Grundtvig Society

“To establish a free and open forum”: A memoir of the founding of the Grundtvig Society By S. A. J. Bradley With the passing of William Michelsen (b. 1913) in October 2001 died the last of the founding fathers of Grundtvig-Selskabet af 8. september 1947 [The Grundtvig Society of 8 September 1947] and of Grundtvig- Studier [Grundtvig Studies] the Society’s year-book.1 It was an appropriate time to recall, indeed to honour, the vision and the enthusiasm of that small group of Grundtvig-scholars - some very reverend and others just a touch irreverent, from several different academic disciplines and callings but all linked by their active interest in Grundtvig - who gathered in the bishop’s residence at Ribe in September 1947, to see what might come out of a cross-disciplinary discussion of their common subject. Only two years after the trauma of world war and the German occupation of Denmark, and amid all the post-war uncertainties, they talked of Grundtvig through the autumn night until, as the clock struck midnight and heralded Grundtvig’s birthday, 8 September, they formally resolved to establish a society that would serve as a free and open forum for the advancement of Grundtvig studies. The biographies of the principal names involved - who were not only theologians and educators but also historians and, conspicuously, literary scholars concerned with Grundtvig the poet - and the story of this post-war burgeoning of the scholarly reevaluation of Grundtvig’s achievements, legacy and significance, form a remarkable testimony to the integration of the Grundtvig inheritance in the mainstream of Danish life in almost all its departments, both before and after the watershed of the Second World War. -

Danmarks Kunstbibliotek the Danish National Art Library

Digitaliseret af / Digitised by Danmarks Kunstbibliotek The Danish National Art Library København / Copenhagen For oplysninger om ophavsret og brugerrettigheder, se venligst www.kunstbib.dk For information on copyright and user rights, please consult www.kunstbib.dk D 53.683 The Ehrich Galleries GDlö ilaøtrrø” (Exclusively) Danmarks Kunstbibliotek Examples French SpanS^^ Flemish Dutch PAINTINGS 463 and 465 Fifth Avenue At Fortieth Street N E W YO R K C IT Y Special Attention Given to the Expertising, Restoration and Framing o f “ (®li fHastrrii” EXHIBITION of CONTEMPORARY SCANDINAVIAN ART Held under the auspices of the AMERICAN-SCANDINAVIAN SOCIETY Introduction and Biographical Notes By CHRISTIAN BRINTON With the collaboration of Director KARL MADSEN Director JENS THUS, and CARL G. LAURIN The American Art Galleries New York December tenth to twenty-fifth inclusive 1912 SCANDINAVIAN ART EXHIBITION Under the Gracious Patronage of HIS MAJESTY GUSTAV V King of Sweden HIS MAJESTY CHRISTIAN X Copyright, 1912 King of Denmark By Christian Brinton [ First Impression HIS MAJESTY HAAKON VII 6,000 Copies King of Norway Held by the American-Scandinavian Society t 1912-1913 in NEW YORK, BUFFALO, TOLEDO, CHICAGO, AND BOSTON Redfield Brothers, Inc. New York INTRODUCTORY NOTE h e A m e r i c a n -Scandinavian So c ie t y was estab T lished primarily to cultivate closer relations be tween the people of the United States of America and the leading Scandinavian countries, to strengthen the bonds between Scandinavian Americans, and to advance the know ledge of Scandinavian culture among the American pub lic, particularly among the descendants of Scandinavians. -

Danish Sixties Avant-Garde and American Minimal Art Max Ipsen

Danish Sixties Avant-Garde and American Minimal Art Max Ipsen “Act so that there is no use in a centre”.1 Gertrude Stein Denmark is peripheral in the history of minimalism in the arts. In an international perspective Danish artists made almost no contributions to minimalism, according to art historians. But the fact is that Danish artists made minimalist works of art, and they did it very early. Art historians tend to describe minimal art as an entirely American phenomenon. America is the centre, Europe the periphery that lagged behind the centre, imitating American art. I will try to query this view with examples from Danish minimalism. I will discuss minimalist tendencies in Danish art and literature in the 1960s, and I will examine whether one can claim that Danish artists were influenced by American minimal art. Empirical minimal art The last question first. Were Danish artists and writers influenced by American minimal art? The straight answer is no. The fact is that they did not know about American minimal art when they first made works, which we today can characterize as minimal art or minimalism. Minimalism was just starting to occur in America when minimalist works of art were made in Denmark. Some Danish artists, all of them linked up with Den eksperimenterende Kunstskole (The Experimenting School of Art), or Eks-skolen as the school is most often called, in Copenhagen, were employing minimalist techniques, and they were producing what one would tend to call minimalist works of art without knowing of international minimalism. One of these artists, Peter Louis-Jensen, years later, in 1986, in an interview explained: [Minimalism] came to me empirically, by experience, whereas I think that it came by cognition to the Americans. -

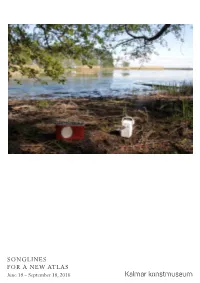

Kalmar Konstmuseum Bita Razavi Same Song, New Songline 2016 Photo by Jaakko Karhunen

SONGLINES FOR A NEW ATLAS June 18 – September 18, 2016 Kalmar konstmuseum Bita Razavi Same Song, New Songline 2016 Photo by Jaakko Karhunen Nadia Kaabi-Linke Meira Ahmemulic Bani Abidi Bita Razavi Karel Koplimets Malene Mathiasson Dzamil Kamanger/Kalle Hamm Linda Persson Curator Torun Ekstrand “I speak to maps. And sometimes they say something back to me. This is not as strange as it sounds, nor is it an unheard of thing. Before maps the world was limitless. It was maps that gave it shape and made it seem like territory, like something that could be posses- sed, not just laid waste and plundered. Maps made places on the edges of the imagination seem graspable and placable.” Abdulrazak Gurnah, By the Sea This summer’s group exhibition at Kalmar konstmuseum takes its point of departure in demarcation lines and in the maps, networks, contexts and identities that can arise in a society in times of migration and refugee ship. Artists have challenged ideas about identity and belonging in all times and can give us new perspectives on questions of place and mobility. “When the Berlin Wall came down in 1989 there were 16 large border barriers between territories world- wide. Today there are 65 of them, either already existing or under construction.” This can be read in an article from the TT News Agency, from the end of last year. Meanwhile, there are almost 60 million refugees in the world. Many historical maps are artworks in themselves. Some maps have changed how we look upon the world. Other maps have been used in warfare, or as tools in the hands of colonial powers. -

Reading Sample

Katharina Alsen | Annika Landmann NORDIC PAINTING THE RISE OF MODERNITY PRESTEL Munich . London . New York CONTENTS I. ART-GEOGRAPHICAL NORTH 12 P. S. Krøyer in a Prefabricated Concrete-Slab Building: New Contexts 18 The Peripheral Gaze: on the Margins of Representation 23 Constructions: the North, Scandinavia, and the Arctic II. SpACES, BORDERS, IDENTITIES 28 Transgressions: the German-Danish Border Region 32 Þingvellir in the Focal Point: the Birth of the Visual Arts in Iceland 39 Nordic and National Identities: the Faroes and Denmark 45 Identity Formation in Finland: Distorted Ideologies 51 Inner and Outer Perspectives: the Painting and Graphic Arts of the Sámi 59 Postcolonial Dispositifs: Visual Art in Greenland 64 A View of the “Foreign”: Exotic Perspectives III. THE SENSE OF SIGHT 78 Portrait and Artist Subject: between Absence and Presence 86 Studio Scenes: Staged Creativity 94 (Obscured) Visions: the Blind Eye and Introspection IV. BODY ImAGES 106 Open-Air Vitalism and Body Culture 115 Dandyism: Alternative Role Conceptions 118 Intimate Glimpses: Sensuality and Desire 124 Body Politics: Sexuality and Maternity 130 Melancholy and Mourning: the Morbid Body V. TOPOGRAPHIES 136 The Atmospheric Landscape and Romantic Nationalism 151 Artists’ Colonies from Skagen to Önningeby 163 Sublime Nature and Symbolism 166 Skyline and Cityscape: Urban Landscapes VI. InnER SpACES 173 Ideals of Dwelling: the Spatialization of an Idea of Life 179 Formations: Person and Interior 184 Faceless Space, Uncanny Emptying 190 Worlds of Things: Absence and Materiality 194 The Head in Space: Inner Life without Boundaries VII. FORM AND FORMLESSNESS 202 In Dialogue with the Avant-garde: Abstractions 215 Invisible Powers: Spirituality and Psychology in Conflict 222 Experiments with Material and Surface VIII. -

Danish Vernacular – Nationalism and History Shaping Education

Danish Vernacular – Nationalism and History Shaping Education Inger Berling Hyams Roskilde University, Roskilde, Denmark ABSTRACT: Despite the number of internationally successful Danish architects like Jacobsen, Utzon and in recent years Ingels just to name a few, Danish architecture has always leaned greatly on international architectural history and theory. This is only natural for a small nation. However, since the beginning of Danish architecture as a professional discipline, there has also been a formation of a certain Danish vernacular. This paper explores how the teaching of and interest in Danish historical buildings could have marked the education of Danish architecture students. Through analysis of the drawings of influential teachers in the Danish school, particularly Nyrop, this development is tracked. This descriptive and analytic work concludes in a perspective on the backdrop of Martin Heidegger’s differentiation between Historie and Geschichte – how history was used in the curriculum and what sort of impact the teachers had on their students. Such a perspective does not just inform us of past practices but could inspire to new ones. KEYWORDS: Danish architecture education, National Romanticism, Martin Nyrop, Kay Fisker Figur 1: Watercolor by Arne Jacobsen, depicting the SAS hotel, Tivoli Gardens and City Hall in Copenhagen. Is there a link between functionalism and Danish vernacular? INTRODUCTION: WHAT IS VERNACULAR? Despite a long and proud tradition of Danish design, there has been very little research into Danish architecture and design education and it was discovering this lack that sparked my research. Through an investigation of different educational practices in the 20th century I am concerned with answering how knowledge is produced and transferred through the act of drawing. -

Hygge & Lykke: Good Old Danish Enclosures Or Gates to a Brave

The Bridge Volume 41 Number 2 Article 5 2018 Hygge & Lykke: Good Old Danish Enclosures or Gates to a Brave New World? Poul Houe Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/thebridge Part of the European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, and the Regional Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Houe, Poul (2018) "Hygge & Lykke: Good Old Danish Enclosures or Gates to a Brave New World?," The Bridge: Vol. 41 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/thebridge/vol41/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Bridge by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. hygge & Lykke: Good Old Danish Enclosures | Poul houe Hygge & Lykke: Good Old Danish Enclosures or Gates to a Brave New World? by Poul houe every year since becoming a Danish expat some forty-five years ago, I’ve spent part of each summer in Denmark. 2017 was no ex- ception, but unlike previous years, this time I reflected explicitly on something most Danes probably take for granted or don’t pay much attention to: their country’s global reputation as the hyggeligste and lykkeligste place on earth (although Denmark came second to Norway in the global happiness rankings in 2017).1 Denmark’s reputation as the happiest (lykkeligste) place on earth is increasingly matched by the claim that it harbors the coziest (hyggeligste) culture imaginable. Many observers and commentators have credited the Danes for their uniquely appealing way of life while trying to unlock “the secret of Danish happiness” and extract “a heartwarming lesson from Den- mark” for the rest of the world. -

STINE BIDSTRUP Danish (B

STINE BIDSTRUP Danish (b. 1982) EDUCATION 2005-06 Post-Baccalaureate (honors) in glass, Rhode Island School of Design, USA 2005-06 Exchange student, Rhode Island School of Design, USA 2004 BA, The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Art, School of Design, Bornholm, Denmark SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2015 To Present What Has Already Past, 7th Floor Gallery, University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA 2013 Knotted Narratives, X-rummet, HUSET i Asnæs, Denmark 2012 Award Recipient of 2012, Hempel Glass Museum, Denmark Rupert’s Chaos, BOX Gallery, Lynfabrikken, Aarhus, Denmark 2011-12 Studies in Search of Order and Chaos, Glass Museum Ebeltoft, Denmark 2010 New Work, Galleri Jytte Møller, Fredericia, Denmark 2009 When the Earth Reflects (with Charlotte Krogh), HUSET i Asnæs, Denmark 2008 Sense of Reflection, Agallery, Copenhagen, Denmark We Map Ourselves Inside of It, Tesch & Hallberg, Copenhagen, Denmark 2006 Double Visions (with Kim Harty), Hillel Gallery, Brown University, Providence, USA SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2017 Great Danes - Danish Glass from Modern Factory Design to Contemporary Art, Hempel Glass Museum, Nykøbing Sj., Denmark Grow, HUSET in Asnæs, Danmark 2016 Great Danes - Danish Glass from Modern Factory Design to Contemporary Art, Glazenhuis Flemish Center for Contemporary Glass Art, Lommel, Belgium Europa grenze(n)loos glas, Glasrijk Tubbergen 2016, Holland FUNN, S12 Gallery, Bergen, Norway 2015 The Process - The International Glass Prize 2015, Glass Museum Glazenhuis, Lommel, Belgium The Soul and The Pawnshop, Sediment Gallery, Richmond, Virginia, -

Museum Act - ACT No

DISCLAIMER: As Member States provide national legislations, hyperlinks and explanatory notes (if any), UNESCO does not guarantee their accuracy, nor their up-dating on this web site, and is not liable for any incorrect information. COPYRIGHT: All rights reserved.This information may be used only for research, educational, legal and non- commercial purposes, with acknowledgement of UNESCO Cultural Heritage Laws Database as the source (© UNESCO). Museum Act - ACT no. 473 of 07/06/2001 BE IT KNOWN that the Folketing has enacted and We Margrethe the Second, by the Grace of God, Queen of Denmark, have given Our Royal Assent to the following Act: Chapter 1 - Purpose 1. The purpose of this Act shall be to promote museum work and cooperation with a view to safeguarding Denmark's cultural and natural heritage and securing access to and knowledge about this heritage and its interaction with the world around us. (2) Unless otherwise provided, the provisions of this Act shall apply to state-owned museums under the Ministry of Culture and to non-state museums receiving state subsidies pursuant to the Act. 2. Through collection, registration, conservation, research and communication the museums shall i) Work for the safeguarding of Denmark's cultural and natural heritage, ii) Illustrate cultural, natural and art history iii) Expand the collections and documentation within their respective areas of responsibility, iv) Make the collections and documentation accessible to the general public, and v) Make the collections and documentation accessible for research, and communicate the results of such research. 3. The museums shall collaborate to promote the tasks referred to in Section 2.