Painwise in Space: the Psychology of Isolation in Cordwainer Smith and James Tiptree, Jr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rediscovery of Man Free Download

THE REDISCOVERY OF MAN FREE DOWNLOAD Cordwainer Smith | 400 pages | 29 Mar 2010 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780575094246 | English | London, United Kingdom The Rediscovery of Man Sure, I can say it has pages of acclaimed stories—every short story that Cordwainer Smith ever wrote. After defeat, after disappointment, after ruin and reconstruction, mankind had leapt among the stars. The Rediscovery of Man Rediscovery of Man, by Cordwainer Smith. The majority of these stories take place 14, yeas into the future, and The Rediscovery of Man this day, present a The Rediscovery of Man worldview, and an astounding examination of human nature. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. This brilliant collection, often cited as the first of its kind, explores fundamental questions about ourselves and our treatment of the universe and other beings around us and ultimately what it means to be human. Cordwainer Smith is a writer like none other. These stories were written in the late 50s, early 60s, and are so intelligent and forward thinking, I'm still stunned. Underpeople do all the hard work, police is made up of robots and telepathic mind control checks that everybody is thinking happy thoughts, or they are sent for re-education. A Cordwainer Smith Panel Discussion. That said, when I said last time that I was relieved that Tiptree's radical feminism never crossed the line into open transphobia, a finger on the monkey's paw curled up and delivered me Smith's "The Tranny Menace from Beyond the Stars" "The Crime and the Glory of Commander Suzdal," about which I have absolutely nothing positive to say. -

Steam Engine Time 5

Steam Engine T ime PRIEST’S ‘THE SEPARATION’ MEMOS FROM NORSTRILIA CENSORSHIP IN AUSTRALIA POLITICS AND SF Harry Hennessey Buerkett James Doig Paul Kincaid Gillian Polack Eric S. Raymond Milan Smiljkovic Janine Stinson Issue 5 September 2006 Steam Engine T ime 5 STEAM ENGINE TIME No. 5, September 2006 is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia ([email protected]) and Janine Stinson, PO Box 248, Eastlake, MI 49626-0248, USA ([email protected]). Members fwa. First edition is in .PDF file format from eFanzines.com or from either of our email addresses. Print edition available for The Usual (letters or substantial emails of comment, artistic contributions, articles, reviews, traded publications or review copies) or subscriptions (Australia: $40 for 5, cheques to ‘Gillespie & Cochrane Pty Ltd’; Overseas: $US30 or £15 for 5, or equivalent, airmail; please send folding money, not cheques). Printed by Copy Place, 415 Bourke Street, Melbourne VIC 3000. The print edition is made possible by a generous financial donation. Graphics Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) (front cover). Photographs Covers of various books and magazines discussed in this issue; plus photos of (p. 5) Christopher Priest, by Ian Maule; (p. 24) Roger Dard, supplied by Kim Huett; (p. 25) Roger Dard fanzine contributions, supplied by Kim Huett; (p. 32) Nigel Burwood, Martin Stone and Bill Blackbeard, by John Baxter; (p. 39) David Boutland. 3 EDITORIAL 1: 32 Letters of comment ‘Dream your dreams’: A meditation on Babylon 5 John Baxter Janine Stinson Rosaleen Love Steve Jeffery 4 EDITORIAL 2 E. B. Frohvet Bruce Gillespie Steve Sneyd Sydney J. -

Single-Gendered Worlds in Science Fiction: Better for Whom? Victor Grech with Clare Thake-Vasallo and Ivan Callus

VECTOR 269 – SPRING 2012 Single-gendered Worlds in Science Fiction: Better for Whom? Victor Grech with Clare Thake-Vasallo and Ivan Callus n excess of one gender is a regular and worlds are commoner than men-only worlds is that a problematic trope in SF, instantly removing any number of writers have speculated whether a world Apotential tension between the two sexes while constructed on strict feminist principles might be utopian simultaneously generating new concerns. While female- rather than dystopian, and ‘for many of these writers, only societies are common, male-only societies are rarer. such a world was imaginable only in terms of sexual This is partly a true biological obstacle because the female separatism; for others, it involved reinventing female and body is capable of bringing a baby forth into the world male identities and interactions’.2 after fertilization, or even without fertilization, so that a These issues have been ably reviewed in Brian prospective author’s only stumbling block to accounting Attebery’s Decoding Gender in Science Fiction (2002), in for the society’s potential longevity. For example, which he observes that ‘it’s impossible in real life to to gynogenesis is a particular type of parthenogenesis isolate the sexes thoroughly enough to demonstrate […] whereby animals that reproduce by this method can absolutes of feminine or masculine behavior’,3 whereas only reproduce that way. These species, such as the ‘within science-fiction, separation by gender has been the salamanders of genus Ambystoma, consist solely of basis of a fascinating series of thought experiments’.4 females which does, occasionally, have sexual contact Intriguingly, Attebery poses the question that a single- with males of a closely related species but the sperm gendered society is ‘better for whom’?5 from these males is not used to fertilise ova. -

VECTOR 58 Is Edited by Bob Parkinson, 106 Ingram Avenue, Aylesbury, Bucks

NO 58 JOHN CROMPTON on CORDWAINER SMITH VECTOR N958 VECTORED 2 C'THEME AND M'STYLE IN CORWAINER SMITH John Crompton U CORDWAINER SMITH: A BRIEF PROFILE Bob Parkinson 12 ANDRE NORTON’S WITCH WORLD FANTASIES Fred Oliphant U COMMUNICATION AND ORGANIZATION Keith Freeman 16 BOOKS 17 cover: Judy Evans & Bob Parkinson interior illustrations (delivered at very short notice): David Rowe for "A Planet Named Shayol" VECTOR 58 is edited by Bob Parkinson, 106 Ingram Avenue, Aylesbury, Bucks. Production Manager: Derek J Rolls Advertising Manager: Roger G. Peyton, 131 Gillhurst Road, Birmingham 1 ?• Published by the British Science Fiction Association, Executive Secretary: Mrs A. E. Walton, 25 Yewdale Crescent, Coventry CV2 2FF. JULY 1971 ftrice: 25 p. BETWEEN TWO WORLDS vectored Among my intentions for this column, it has Characteristically, the situation that Mailer found been my aim with each issue to write of one was ambiguous Oriana Fallaci, who had explored much book that has caught my attention in the months the same route earlier in her If The Sun Dies, wrote a immediately before Thus far we have had one book of conversion literature along side St Augustine's sf book written by a "mainstream" author and a Confessions or William Burrough's Nova Express But fantasy written by a non-sf author This time Mailer, sandwiching Apollo 11 between the failure of round I want to discuss a non-sf, non-fiction his mayoraiity campaign in New York and the break-up book written by someone outside the field entir- of his marriage, winds up finding that he is -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Race of Machines: A Prehistory of the Posthuman Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90d94068 Author Evans, Taylor Scott Publication Date 2018 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Race of Machines: A Prehistory of the Posthuman A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Taylor Scott Evans December 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Sherryl Vint, Chairperson Dr. Mark Minch-de Leon Mr. John Jennings, MFA Copyright by Taylor Scott Evans 2018 The Dissertation of Taylor Scott Evans is approved: ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgments Whenever I was struck with a particularly bad case of “You Should Be Writing,” I would imagine the acknowledgements section as a kind of sweet reward, a place where I can finally thank all the people who made every part of this project possible. Then I tried to write it. Turns out this isn’t a reward so much as my own personal Good Place torture, full of desire to acknowledge and yet bereft of the words to do justice to the task. Pride of place must go to Sherryl Vint, the committee member who lived, as it were. She has stuck through this project from the very beginning as other members came and went, providing invaluable feedback, advice, and provocation in ways it is impossible to cite or fully understand. -

Between Mottile and Ambiloxi: Cordwainer Smith As a Southern Writer

[Published in Extrapolation, 2001, Vol. 42, pp. 124-136.] Between Mottile and Ambiloxi: Cordwainer Smith as a Southern Writer Alan C. Elms Cordwainer Smith’s science fiction has often been described as Chinese in form and to some extent in themes and characterization.1 Beyond the evident qualities of the fiction itself, there are good reasons to assume Chinese influences on his work. Under his real name, Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger, the author spent years in China from childhood onward, spoke Chinese fluently, read the Chinese classics in their original versions, and was a Professor of Asiatic Politics at the Johns Hopkins University. Linebarger also spent substantial periods of time in France, Germany, and England, and he acknowledged the influence of various European authors on the Cordwainer Smith stories. However, another important aspect of Linebarger’s life and fiction has received little if any attention. Linebarger’s earliest distinct memories dated from a three-year period before he ever saw China or other foreign lands. His memories of this period were later transformed and incorporated into at least two of his most important stories, and influenced elements of other stories as well. During this period, when Linebarger was three to nearly six years old, his family lived in southern Mississippi, in a land of bayous and white-columned mansions. Linebarger later remembered this time and place as an isolated paradise. In its particulars, it was clearly a Southern paradise. How did Paul Linebarger come to spend those crucial childhood years in Mississippi? His parents did not think of themselves as Southerners, and had no close relatives from the deep South. -

PDF Download the Rediscovery Of

THE REDISCOVERY OF MAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cordwainer Smith | 400 pages | 29 Mar 2010 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780575094246 | English | London, United Kingdom The Rediscovery of Man: The Complete Short Science Fiction of Cordwainer Smith by Cordwainer Smith Anderson, Brian D. Armstrong, Kelley. Atwood, Margaret. Abnett, Dan. Albert, Melissa. Anderson, Howard L. Arnold, Edwin L. Aubrey, Frank. Abraham, Daniel. Alderman, Naomi. Anderson, Kevin J. Arnold, Elana K. Audley, Anselm. Acevedo, Mario. Aldiss, Brian W. Anderson, M. Arnold, Luke. Auel, Jean M. Ackley-McPhail, Danielle. Alexander, Alma. Anderson, Poul. Arnopp, Jason. Auxier, Jonathan. Acosta, Marta. Alexander, Lloyd. Anderson, Taylor. Arthur, Keri. Averill, Alan. Adams, C. Alexander, Rebecca. Anderton, Jo. Aryan, Stephen. Avery, Fiona. Adams, Douglas. Alexander, William. Andrews, Ilona. Asaro, Catherine. Aveyard, Victoria. Adams, Guy. Alison, Lorence. Anthony, Piers. Ash, Sarah. Adams, Richard. Allen, Harper. Applegate, K. Ashby, Madeline. Axler, James. Adams, Robert. Allen, Justin. Appleton, Victor. Asher, Neal. Addison, Katherine. Almasi, G. Arbuthnott, Gill. Ashton, Dyrk. Adeyemi, Tomi. Almond, David. Archer, Alex. Ashwood, Sharon. Aguirre, Ann. Alpert, Mark. Archer, E. Asimov, Isaac. Don't see who you're looking for? Please try the search box located under this menu. Bach, Rachel. Barry, Max. Bernstein, Nina. Borchardt, Alice. Brooks, Max. Bacigalupi, Paolo. Barzak, Christopher. Bertin, Joanne. Borges, Jorge Luis. Brooks, Terry. Badger, Darcie Little. Basile, Giambattisto. Bester, Alfred. Bornikova, Phillipa. Brooks-Dalton, Lily. Badger, Hilary. Bateman, Sonya. Beukes, Lauren. Boston, Lucy M. Brooks-Janowiak, Jean. Bailey, Dale. Bates, Callie. Beutner, Katharine. Boucher, Anthony. Bross, Lanie. Bailey, Paul. Bates, Harry. Bhathena, Tanaz. Bourne, J. Brouneus, Fredrik. Baird, Alison. Batson, Wayne Thomas. Bickle, Laura. -

SCIENCE FICTION FALL T)T1T 7TT?TI7 NUMBER 48 1983 Mn V X J J W $2.00 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O

SCIENCE FICTION FALL T)T1T 7TT?TI7 NUMBER 48 1983 Mn V X J_J W $2.00 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O. BOX 11408 PORTLAND, OR 97211 AUGUST, 1983 —VOL.12, NO.3 WHOLE NUMBER 98 PHONE: (503) 282-0381 RICHARD E. GEIS—editor & publisher PAULETTE MINARE', ASSOCIATE EDITOR PUBLISHED QUARTERLY FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. SINGLE COPY - $2.00 ALIEN THOUGHTS BY THE EDITOR.9 THE TREASURE OF THE SECRET C0RDWAINER by j.j. pierce.8 LETTERS.15 INTERIOR ART-- ROBERT A. COLLINS CHARLES PLATT IAN COVELL E. F. BLEILER ALAN DEAN FOSTER SMALL PRESS NOTES ED ROM WILLIAM ROTLSER-8 BY THE EDITOR.92 KERRY E. DAVIS RAYMOND H. ALLARD-15 ARNIE FENNER RICHARD BRUNING-20199 RONALD R. LAMBERT THE VIVISECTOR ATOM-29 F. M. BUSBY JAMES MCQUADE-39 BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER.99 ELAINE HAMPTON UNSIGNED-35 J.R. MADDEN GEORGE KOCHELL-38,39,90,91 RALPH E. VAUGHAN UNSIGNED-96 ROBERT BLOCH TWONG, TWONG SAID THE TICKTOCKER DARRELL SCHWEITZER THE PAPER IS READY DONN VICHA POEMS BY BLAKE SOUTHFORK.50 HARLAN ELLISON CHARLES PLATT THE ARCHIVES BOOKS AND OTHER ITEMS RECEIVED OTHER VOICES WITH DESCRIPTION, COMMENTARY BOOK REVIEWS BY AND OCCASIONAL REVIEWS.51 KARL EDD ROBERT SABELLA NO ADVERTISING WILL BE ACCEPTED RUSSELL ENGEBRETSON TEN YEARS AGO IN SF - SUTER,1973 JOHN DIPRETE BY ROBERT SABELLA.62 Second Class Postage Paid GARTH SPENCER at Portland, OR 97208 THE STOLEN LAKE P. MATHEWS SHAW NEAL WILGUS ALLEN VARNEY Copyright (c) 1983 by Richard E. MARK MANSELL Geis. One-time rights only have ALMA JO WILLIAMS been acquired from signed or cred¬ DEAN R. -

THR 1976 1.Pdf

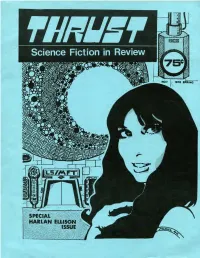

creative writers and artists appear in rounter tfjrusit COLLEGE PARK, MD. 20740 50C thrust contents Cover by Steve Hauk.....page 1 Contents page (art by Richard Bryant).page 3 Editorial by Doug Fratz (art by Steve Hauk).page 4 THRUST INTERVIEW: HARLAN ELLISON by Dave Bischoff and Chris Lampton (axt by Steve Hauk)...page 5 Alienated Critic by Doug Fratz (art by Don Dagenais).page 12 Conventions (art by Jim Rehak).page 13 Centerspread art by Richard Bryant.page 14 Harlan Ellison vs. The Spawning Bischii by David F. Bischoff.page 16 Book Reviews by Chris Lampton, Linda Isaacs, Dave Bischoff, Melanie Desmond and Doug Fratz (art by Richard Bryant and Dennis Bailey ).page 21 ADVERTISING: Counter-Thrust Fantasy Magazine...page 2 The Nostalgia Journal.....page 27 Crazy A1 ’ s C omix and Nostalgia Shop....page 28 staff Editor-in-Chief: Computer Layout: LEE MOORE and NATALIE PAYMER Doug Fratz Art Director: Managing Editor: STEVE HAUK Editorial Assistants: Dennis Bailey RON WATSON and BARBARA GOLDFARB Staff Writers: Associate Editor: DAVE BISCHOFF Melanie Desmond EE SEE? EDITORIAL by Doug Fratz I created THRUST SCIENCE FICTION more than find it incredibly interesting reading it over three years ago, and edited and published five for the tenth or twelveth time. Ted Cogswell issues, between February 1973 and May 1974, should take special note. completely from my own funds. When I received In addition, THRUST will have a sister my degree from the University of Maryland, I magazine of sorts, COUNTER-THRUST, to be pub¬ decided to turn THRUST over to other editors. lished yearly, once each summer. -

The Rediscovery of Man Free Ebook

FREETHE REDISCOVERY OF MAN EBOOK Cordwainer Smith | 400 pages | 29 Mar 2010 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780575094246 | English | London, United Kingdom The Rediscovery of Man, by Cordwainer Smith I can't tell you what this book is like. Sure, I can say it has pages of acclaimed stories—every short story that Cordwainer Smith ever wrote. I can say that the devoted people at the New England Science Fiction Association outdid themselves in creating the most accurate texts possible. They also did this with the companion volume Norstriliathe only full-length science fiction novel that Cordwainer Smith wrote. But still So I'm going to let my father himself introduce his own book, by quoting The Rediscovery of Man beginnings of some of the stories. If that makes you want to The Rediscovery of Man more, you can get The Rediscovery of Man quickly from a variety of places online No, No, Not Rogov! War No. Please note: There is a British paperback with the identical title The Rediscovery of Man which is available at the British Amazon, but it is a reprint The Rediscovery of Man the old Ballentine paperback Best of Cordwainer Smithand it only contains a dozen stories. That golden shape on the golden steps shook and fluttered like a bird gone mad—like a bird imbued with an intellect and a soul, and, nevertheless, driven mad by ecstasies and terrors beyond human understanding—ecstasies drawn momentarily down into reality by the consummation of superlative art. A thousand worlds watched. Had the ancient calendar continued, this would have been AD 13, After defeat, after disappointment, after ruin and reconstruction, mankind had leapt among the stars. -

Behind the Jet-Propelled Couch: Cordwainer Smith and Kirk Allen

Behind the Jet-Propelled Couch: Cordwainer Smith and Kirk Allen Alan C. Elms [Originally published in the New York Review of Science Fiction, May 2002] In 1978 I began to pursue the question of whether Paul Linebarger, aka Cordwainer Smith, had been the patient in “The Jet-Propelled Couch,” a psychoanalytic case history written by Robert Lindner. Over the past quarter-century I’ve accumulated more information and ideas on that question than I can fully present here. Instead I’ll use the format of a FAQ – a list of “frequently asked questions” and fairly brief answers. 1.) Why are you doing this? a) As a follow-up to one of the most famous case histories ever published. Robert Lindner’s book, The Fifty-Minute Hour, has sold several million copies since its first publication in 1955 and has remained almost constantly in print. The book’s most fascinating case, “The Jet-Propelled Couch,” has been reprinted in magazines and anthologies, has been dramatized on live TV, has repeatedly been optioned for a feature- length film, and even provided the basis for a Stephen Sondheim musical that (like all those potential film versions) was never completed. b) The case study has been of special interest to sf fans ever since its early reprinting in the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. Its protagonist, a patient called Kirk Allen, experienced what struck many fans as the ideal psychosis: he spontaneously found himself living a heroic life as “Lord of a planet in an interplanetary empire,” far in the future (Fifty-Minute Hour, 250). -

Science Fiction As Media Theory Wednesdays 2:00-4:50 ASCJ Henry Jenkins [email protected] Office Hours by Appointment, Contact Am

Science Fiction as Media Theory Wednesdays 2:00-4:50 ASCJ Henry Jenkins [email protected] Office hours by appointment, contact Amanda Ford at: [email protected] This class explores the ways that science fiction—sometimes known as speculative fiction—has historically functioned as a form of vernacular theory about media technologies, practices, and institutions. As recent writings about “design fictions” illustrate, these speculations have in turn inspired the developers and of new technologies as well as those who create content for such platforms, helping to frame our expectations about the nature of media change. And, increasingly, media theorists—raised in a culture where science fiction has been a pervasive influence—are drawing on its metaphors as they speculate about virtual worlds, cyborg feminism, post-humanism, and afro-futurism, among a range of other topics. This seminar will explore the multiple intersections between science fiction and media theory, reading literary and filmic fictions as theoretical speculations and classic and contemporary theory as forms of science fiction. The scope of the course ranges from technological Utopian writers from the early 20th century to contemporary imaginings of digital futures and steampunk pasts. Not simply a course on science fiction as a genre, this seminar will invite us to explore what kinds of cultural work science fiction performs and how it has contributed to larger debates about communication and culture. By the end of the course, students will be able to: · describe the historic relationship between speculative fiction and media theory · explain key movements in science fiction, such as technological utopianism, cyberpunk, steampunk, and discuss their relationship to larger theories of media change.