2013-09-04-Brown Memo in Opposition to Request for Gag Order

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wikileaks and the Afterlife of Collateral Murder

International Journal of Communication 8 (2014), Feature 2593–2602 1932–8036/2014FEA0002 WikiLeaks and the Afterlife of Collateral Murder CHRISTIAN CHRISTENSEN Stockholm University, Sweden In this essay, the author considers not only what is shown in the WikiLeaks Collateral Murder video but reflects upon what the act of uploading this video symbolized and continues to symbolize and how the multifaceted symbolic value of the video has led to its steady inscription and reinscription into the public consciousness during a wide variety of popular and political debates. Apart from the disturbing content of the film, showing a potentially criminal act, the author argues that the uploading of the film was itself an act of dissent and, thus, a challenge to U.S. power. This combination of content and context makes the WikiLeaks Collateral Murder video an interesting case study that touches upon several key areas within academic study. Keywords: WikiLeaks, journalism, war, visual culture, Iraq, Collateral Murder, video Introduction On April 5, 2010, WikiLeaks released Collateral Murder, a video showing a July 12, 2007, U.S. Apache attack helicopter attack upon individuals in New Baghdad. Among the more than 23 people killed by the 30-mm cannon fire were two Reuters journalists. WikiLeaks published this statement in conjunction with the release: WikiLeaks has released a classified U.S. military video depicting the indiscriminate slaying of over a dozen people in the Iraqi suburb of New Baghdad — including two Reuters news staff. Reuters has been trying to obtain the video through the Freedom of Information Act, without success since the time of the attack. -

Barrett Brown Is Anonymous

Case 3:12-cr-00317-L Document 90 Filed 09/04/13 Page 1 of 13 PageID 458 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS DALLAS DIVISION ________________________________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA § § No: 3:12-CR-317-L v. § No: 3:12-CR-413-L § No: 3:13-CR-030-L BARRETT LANCASTER BROWN § MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANT’S OPPOSITION TO GOVERNMENT’S REQUEST FOR A GAG ORDER BARRETT LANCASTER BROWN, through his counsel, respectfully submits this memorandum to set the framework for oral argument on September 4, 2013, and to enter exhibits that Mr. Brown believes are relevant to the courts determination.1 STATEMENT OF FACTS A. Barrett Brown Barrett Lancaster Brown is a thirty-two year old American satirist, author and journalist. His work has appeared in Vanity Fair, the Guardian, Huffington Post, True/Slant, the Skeptical Inquirer and many other outlets. See Summary Chart of Select Publications by Barrett Brown, Exh. A. He is the co-author of a satirical book on creationism entitled Flock of Dodos: Behind Modern Creationism, Intelligent Design and the Easter Bunny. As described by Alan Dershowitz, Felix Frankfurter Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, “Flock of Dodos is in the great tradition of debunkers with a sense of humor, from Thomas Paine to Mark Twain.” See Flock of Dodos (book cover), Exh. B. Indeed, Mr. Brown’s use of sarcasm, humor and 1 Mr. Brown enters these exhibits, mainly consisting of articles and commentary, for limited purpose of assisting the Court’s determination in this matter, and not for the truth of the matter asserted by the statements therein. -

TVRA 4040 Spring 2015

BROOKLYN COLLEGE Department of Television and Radio TVRA 4040 (Section RQ2): Convergent News Platforms Spring Semester 2015 Professor John Anderson Class meets Thursdays, 2:15-6:45 PM / 302 Whitehead Hall (Radio Lab) Contact: 404S Whitehead Hall / (608) 395-4389 / [email protected] / @diymediadotnet Office Hours: Wednesday 4:00-5:30 PM / Thursday 12:30-2:00 PM in 404S Whitehead or by appointment Course Description Catalog Description: Exploration of online platforms that extend the reach of broadcast media. Introduction to the tools and techniques of online newsgathering and production, with special focus on the effective use of social media and livestreaming. Production of content for the Brooklyn News Service. Detailed Description: Media convergence is loosely defined as the blurring of previously distinctive media systems, and the settlement for all of them on a unified distribution platform— today, we call this the Internet. Convergence has been an incredibly disruptive force in the field of journalism, but it has also created new opportunities to find and tell stories. This class is an introduction into the tools and techniques for doing journalism on convergent news platforms. First, the good news: this is an emerging field where there are no hard-and-fast work-protocols (save for those traditionally defined by the standards of quality journalism, which are the same regardless of platform), so we have a lot of latitude in how we navigate this course. This is also the challenge: because journalists are effectively making up the workflow for these new platforms as we go along, there very few definitive “lessons” to be taught regarding convergent news reporting. -

Amicus Brief

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS DALLAS DIVISION _______________________________________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA § § No. 3:12-cr-413-L v. § § BARRETT LANCASTER BROWN BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF ELECTRONIC FRONTIER FOUNDATION, REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS, REPORTERS WITHOUT BORDERS, FREEDOM OF THE PRESS FOUNDATION, AND PEN AMERICAN CENTER IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANT BARRETT BROWN’S MOTION TO DISMISS THE SUPERSEDING INDICTMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS STATEMENT OF INTEREST ..........................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................2 BACKGROUND ...............................................................................................................................3 I. ANONYMOUS AND THE HBGARY AND STRATFOR HACKS ................................. 3 II. JOURNALIST BARRETT BROWN CROWDSOURCES REVIEW OF THE STRATFOR FILES ............................................................................................................. 6 III. LINKING IS AN INTEGRAL PART OF JOURNALISM .............................................. 12 ARGUMENT .................................................................................................................................. 14 I. THE FIRST AMENDMENT PROTECTS THE PUBLICATION OF LAWFULLY- OBTAINED, TRUTHFUL INFORMATION ABOUT A MATTER OF PUBLIC CONCERN ....................................................................................................................... -

The Masked Avengers: How Anonymous Incited Online

A REPORTER AT LARGE | SEPTEMBER 8, 2014 ISSUE The Masked Avengers How Anonymous incited online vigilantism from Tunisia to Ferguson. BY DAVID KUSHNER Anyone can join Anonymous simply by claiming affiliation. An anthropologist says that participants “remain subordinate to a focus on the epic win—and, especially, the lulz.” n the mid-nineteen-seventies, when Christopher Doyon was a child in rural Maine, he spent Ihours chatting with strangers on CB radio. His handle was Big Red, for his hair. Transmitters lined the walls of his bedroom, and he persuaded his father to attach two directional antennas to the roof of their house. CB radio was associated primarily with truck drivers, but Doyon and others used it to form the sort of virtual community that later appeared on the Internet, with self- selected nicknames, inside jokes, and an earnest desire to effect change. Doyon’s mother died when he was a child, and he and his younger sister were reared by their father, who they both say was physically abusive. Doyon found solace, and a sense of purpose, in the CB-radio community. He and his friends took turns monitoring the local emergency channel. One friend’s father bought a bubble light and affixed it to the roof of his car; when the boys heard a distress call from a stranded motorist, he’d drive them to the side of the highway. There wasn’t much they could do beyond offering to call 911, but the adventure made them feel heroic. Small and wiry, with a thick New England accent, Doyon was fascinated by “Star Trek” and Isaac Asimov novels. -

ABSTRACT the Rhetorical Construction of Hacktivism

ABSTRACT The Rhetorical Construction of Hacktivism: Analyzing the Anonymous Care Package Heather Suzanne Woods, M.A. Thesis Chairperson: Leslie A. Hahner, Ph.D. This thesis uncovers the ways in which Anonymous, a non-hierarchical, decentralized online collective, maintains and alters the notion of hacktivism to recruit new participants and alter public perception. I employ a critical rhetorical lens to an Anonymous-produced and –disseminated artifact, the Anonymous Care Package, a collection of digital how-to files. After situating Anonymous within the broader narrative of hacking and activism, this thesis demonstrates how the Care Package can be used to constitute a hacktivist identity. Further, by extending hacktivism from its purely technological roots to a larger audience, the Anonymous Care Package lowers the barrier for participation and invites action on behalf of would-be members. Together, the contents of the Care Package help constitute an identity for Anonymous hacktivists who are then encouraged to take action as cyberactivists. The Rhetorical Construction of Hacktivism: Analyzing the Anonymous Care Package by Heather Suzanne Woods, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of Communication David W. Schlueter, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee Leslie A. Hahner, Ph.D., Chairperson Martin J. Medhurst, Ph.D. James M. SoRelle, Ph.D. Accepted by the Graduate School May 2013 J. Larry Lyon, Ph.D., Dean Page bearing signatures is kept on file in the Graduate School Copyright © 2013 by Heather Suzanne Woods All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................................ -

Journalist Barrett Brown Sentenced to 63 Months in Prison for Linking to Hacked Material; Read His Speech Here

Journalist Barrett Brown Sentenced to 63 Months in Prison for Linking to Hacked Material; Read his Speech Here By Justin King Region: USA Global Research, January 23, 2015 Theme: Law and Justice, Police State & The Anti-Media 22 January 2015 Civil Rights Persecuted journalist Barrett Brown plans to use his opportunity to address the court at his sentencing to continue to defend his colleagues that are also being persecuted. The government extorted a guilty plea from him by threatening 105 years in prison: he’s currently facing around eight. All indications are that he signed a non-cooperating plea deal in which he admits only his role. As Barrett Brown joins the ranks of America’s other political prisoners, the American people need to review his words and ask themselves if this is actually the government they want. Do they want to live in a society where journalists are targeted by federal agents simply because they revealed the truth? A society where the government exercises so much control over the corporate media, that the fifth estate remains silent, while one of their own is carted off to prison? There isn’t much that can be added to Brown’s statement, as reported by the Daily Dot: *** Good afternoon, Your Honor. The allocution I give today is going to be a bit different from the sort that usually concludes a sentencing hearing, because this is an unusual case touching upon unusual issues. It is also a very public case, not only in the sense that it has been followed closely by the public, but also in the sense that it has implications for the public, and even in the sense that the public has played a major role, because, of course, the great majority of the funds for my legal defense was donated by the public. -

Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy the Many Faces of Anonymous

hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy the many faces of anonymous Gabriella Coleman London • New York Hacker Hoaxer Whistleblower 2015 PB 13-08-15.indd 3 8/13/2015 3:44:42 PM Epilogue: The State of Anonymous “I have grown to love secrecy. It seems to be the one thing that can make modern life mysterious or marvelous to us. The commonest thing is delightful if only one hides it.” Oscar Wilde “The political education of apolitical technical people is extra ordinary.” Julian Assange he period described in this book may seem to many to represent the pinnacle of Anonymous activity: their Tsupport role in the various movements that constituted the Arab Spring; the high-profile media attention garnered by the gutsy LulzSec and AntiSec hacks; the ever growing com- mitment to domestic social justice issues seen in engagements against rape culture and police brutality. Unsurprisingly, this impressive flurry of protest activity was met with similarly impressive law enforcement crackdowns. Throughout Europe, Asia, Australia, and the Americas, law enforcement officials detained over one hundred Anonymous activists—including many of the figures profiled in this book: Jeremy Hammond and John Borell in the United States, and Ryan Ackroyd and Mustafa Al-Bassam in the United Hacker Hoaxer Whistleblower 2015 PB 13-08-15.indd 401 8/13/2015 3:44:54 PM 402 hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy Kingdom. Others arrested were geeky activists whose “crime” had been to simply channel a small portion of their computer resources toward DDoS campaigns organized by Anonymous in an effort to collectively shame financial organizations, such as PayPal when they caved to government pressure and terminated all services to the embattled whistleblowing organ- ization WikiLeaks. -

Journalist Barrett Brown's Day of Reckoning. the Machinations of The

Journalist Barrett Brown’s Day of Reckoning. The Machinations of the US National Security Apparatus By Douglas Lucas Region: USA Global Research, January 23, 2015 Theme: Police State & Civil Rights WhoWhatWhy This article was first published by WhoWhatWhy. A feisty, confrontational journalist who exposed explosive details about the machinations of the national security apparatus and faced more than a century in prison has been sentenced to five years and three months. For more than 1,000 days, the 33-year-old writer has been jailed awaiting resolution of a case that stands to set a frightening precedent for free expression in the Internet era. Brown’s trial mostly revolved around an indictment for sharing a hyperlink in the course of journalistic research—construed by the Department of Justice as trafficking in identity-theft data—and making a series of hyperbolic, rambling threats against an FBI agent on YouTube. Even during his sentencing, Brown displayed the instinctive defiance that made him an easy target for the authorities. In a statement to the court, he accused the government of lying at length to make their case against him, while acknowledging that he did at times break the law. In referring to how prosecutors flip-flopped over whether he was a journalist, he said: “What conclusion can one draw from this sort of reasoning other than that you are whatever the FBI finds it convenient for you to be at any given moment. This is not the rule of law, your honor, it is the rule of law enforcement, and it is very dangerous.” In an interview with WhoWhatWhy from jail, Brown said the FBI had lied in court. -

Curriculum Vitae

E. Gabriella Coleman Wolfe Chair in Scientific and Technological Literacy McGill University (last revised January, 2016) Department of Art History and Communication Studies McGill University 853 Sherbrooke Street West Montreal, QC H3A 0G5 Canada http://gabriellacolman.org [001] 514-398-8572 [email protected] Citizenship: United States of America Education University of Chicago, Chicago, IL Ph.D., Socio-cultural Anthropology, August 2005 M.A., Socio-cultural Anthropology, August 1999 Dissertation: “The Social Construction of Freedom in Free and Open Source Software: Hackers, Ethics, and the Liberal Tradition” Research location: San Francisco, CA and the Netherlands Funding: SSRC and NSF, August 2001-May 2003 Columbia University, New York, NY B.A., Religious Studies, May 1996 Positions Associate Professor and Wolfe Chair in Scientific and Technological Literacy, Department of Art History and Communication Studies (Affiliated with the Department of Anthropology) McGill University, Montreal, QC May 2014-present Assistant Professor and Wolfe Chair in Scientific and Technological Literacy, Department of Art History and Communication Studies (Affiliated with the Department of Anthropology) McGill University, Montreal, QC January 2012-May 2014 Faculty Associate, Berkman Center for Internet & Society Harvard University, Cambridge, MA September 2013-present Assistant Professor, Department of Media, Culture, and Communication Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development 1 New York University, New York, NY September 2007-December -

Dinner Highlights Foreign Correspondents and OPC Jubilee

THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB OF AMERICA, NEW YORK, NY • April 2014 Dinner Highlights Foreign Correspondents and OPC Jubilee EVENT PREVIEW: APRIL 24 by Sonya K. Fry All OPC Awards Dinners are special to the Club. Still, in the past few years, hearts and minds have been focused on making the OPC’s 75th Anniversary Awards Dinner on Thursday, April 24 at the Mandarin Oriental Hotel an extra special occa- From left: Samantha Power, Bob Simon and David Muir sion. Early in the day, OPC represen- for Time. She became a scholar of CBS News. He has also reported tatives will participate in a special U.S. foreign policy and an advisor from the CBS London and Tel Aviv ceremony to flick the switch that to then-Senator Barack Obama and bureaus and in 1987 was named the lights up the Empire State Build- subsequently President Obama. CBS News Chief Middle East Cor- ing. Throughout the dinner, the New OPC President Michael Serrill respondent. He has won several OPC York landmark will be bathed in blue has selected veteran foreign corre- awards, most notably for coverage of — the official color of the OPC — in spondent Bob Simon as this year’s Vietnam, Egypt and the Rabin assas- honor of the Club’s anniversary and recipient of the OPC President’s sination in Israel. He is currently a gala. Award. Simon began his reporting full-time correspondent for “CBS-60 The keynote speaker is former career 42 years ago in Vietnam for (Continued on Page 2) foreign correspondent and current U.S. -

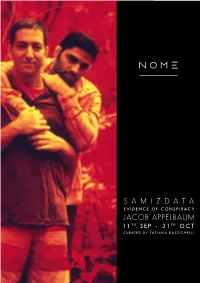

SAMIZDATA-By-Jacob-Appelbaum

SAMIZDATA: HUMAN P2P NETWORKS AS ARTISTIC EVIDENCE BY TATIANA BAZZICHELLI Within the framework of my research on the concept ideals and political views. The focal point in my conversations of networked art, I’ve written that art is not merely to be with Jacob Appelbaum leading up to this exhibition was not identified with the artistic object itself, but through the nets in identifying the show as a celebration of the Snowden of relationships and connections that happen before, during affair, but of the people who made it possible – Bill Binney, and after the realization of the artwork. What we experience Laura Poitras, Glenn Greenwald (with David Miranda), Julian in Jacob Appelbaum’s exhibition SAMIZDATA: Evidence of Assange and Sarah Harrison – as well as others connected Conspiracy are six cibachrome prints, portraying people with the fight for social justice and civil liberty, as in the case whose work and life he admires and with whom he has worked of Ai Weiwei, who is also connected to Appelbaum through together in various forms, and two installation projects on the their P2P (Panda-to-Panda) project. Snowden files and related classified documents. But beneath the final artistic result lies a deep network of connections - It was a combination of events and actions culminating in the invisible in the gallery space, but at the core of this show. Snowden affair that brought this group of people together – people not chosen by Snowden himself, but who, as The title of the exhibition exemplifies it well: “Samizdata”, he has described when referring to Laura Poitras, “chose inspired by the Russian samizdat, which etymologically themselves”.