Avocado Production in California: a Cultural Handbook for Growers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Avocado Production in Home Gardens Revised

AVOCADO PRODUCTION IN HOME GARDENS Author: Gary S. Bender, Ph.D. UCCE Farm Advisor Avocados are grown in home Soil Requirements gardens in the coastal zone of A fine sandy loam with good California from San Diego north drainage is necessary for long life to San Luis Obispo. Avocados and good health of the tree. It is (mostly Mexican varieties) can better to have deep soils, but also be grown in the Monterey – well-drained shallow soils are Watsonville region, in the San suitable if irrigation is frequent. Francisco bay area, and in the Clay soils, or shallow soils with “banana-belts” in the San Joaquin impermeable subsoils, should not Valley. Avocados are grown successfully in be planted to avocados. Mulching avocados frost-free inland valleys in San Diego County with a composted greenwaste (predominantly and western Riverside County, but attention chipped wood) is highly beneficial, but should be made to locating the avocado tree manures and mushroom composts are usually on the warmest microclimates on the too high in salts and ammonia and can lead to property. excessive root burn and “tip-burn” in the leaves. Manures should never be added to Climatic Requirements the soil back-fill when planting a tree. The Guatemalan races of avocado (includes varieties such as Nabal and Reed) are more Varieties frost-tender. The Hass variety (a Guatemalan/ The most popular variety in the coastal areas Mexican hybrid which is mostly Guatemalan) is Hass. The peel texture is pebbly, peel is also very frost tender; damage occurs to the color is at ripening, and it has excellent flavor fruit if the winter temperature remains at 30°F and peeling qualities. -

Avocado Carbohydrate Fluctuations. II. Fruit Growth and Ripening

J. AMER. SOC. HORT. SCI. 124(6):676–681. 1999. ‘Hass’ Avocado Carbohydrate Fluctuations. II. Fruit Growth and Ripening Xuan Liu, Paul W. Robinson, Monica A. Madore, Guy W. Witney,1 and Mary Lu Arpaia2 Department of Botany and Plant Sciences, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521 ADDITIONAL INDEX WORDS. ‘Hass’ avocado, ‘Duke 7’ rootstock, D-mannoheptulose, Persea americana, perseitol, soluble sugar, starch ABSTRACT. Changes in soluble sugar and starch reserves in avocado (Persea americana Mill. on ‘Duke 7’ rootstock) fruit were followed during growth and development and during low temperature storage and ripening. During the period of rapid fruit size expansion, soluble sugars accounted for most of the increase in fruit tissue biomass (peel: 17% to 22%, flesh: 40% to 44%, seed: 32% to 41% of the dry weight). More than half of the fruit total soluble sugars (TSS) was comprised of the seven carbon (C7) heptose sugar, D-mannoheptulose, and its polyol form, perseitol, with the balance being accounted for by the more common hexose sugars, glucose and fructose. Sugar content in the flesh tissues declined sharply as oil accumulation commenced. TSS declines in the seed were accompanied by a large accumulation of starch (≈30% of the dry weight). During postharvest storage at 1 or 5 °C, TSS in peel and flesh tissues declined slowly over the storage period. Substantial decreases in TSS, and especially in the C7 sugars, was observed in peel and flesh tissues during fruit ripening. These results suggest that the C7 sugars play an important role, not only in metabolic processes associated with fruit development, but also in respiratory processes associated with postharvest physiology and fruit ripening. -

Postulated Physiological Roles of the Seven-Carbon Sugars, Mannoheptulose, and Perseitol in Avocado

J. AMER. SOC. HORT. SCI. 127(1):108–114. 2002. Postulated Physiological Roles of the Seven-carbon Sugars, Mannoheptulose, and Perseitol in Avocado Xuan Liu,1 James Sievert, Mary Lu Arpaia, and Monica A. Madore2 Department of Botany and Plant Sciences, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521 ADDITIONAL INDEX WORDS. ‘Hass’ avocado on ‘Duke 7’ rootstock, phloem transport, ripening, Lauraceae ABSTRACT. Avocado (Persea americana Mill.) tissues contain high levels of the seven-carbon (C7) ketosugar mannoheptulose and its polyol form, perseitol. Radiolabeling of intact leaves of ‘Hass’ avocado on ‘Duke 7’ rootstock indicated that both perseitol and mannoheptulose are not only primary products of photosynthetic CO2 fixation but are also exported in the phloem. In cell-free extracts from mature source leaves, formation of the C7 backbone occurred by condensation of a three-carbon metabolite (dihydroxyacetone-P) with a four-carbon metabolite (erythrose-4-P) to form sedoheptulose-1,7- bis-P, followed by isomerization to a phosphorylated D-mannoheptulose derivative. A transketolase reaction was also observed which converted five-carbon metabolites (ribose-5-P and xylulose-5-P) to form the C7 metabolite, sedoheptu- lose-7-P, but this compound was not metabolized further to mannoheptulose. This suggests that C7 sugars are formed from the Calvin Cycle, not oxidative pentose phosphate pathway, reactions in avocado leaves. In avocado fruit, C7 sugars were present in substantial quantities and the normal ripening processes (fruit softening, ethylene production, and climacteric respiration rise), which occurs several days after the fruit is picked, did not occur until levels of C7 sugars dropped below an apparent threshold concentration of ≈20 mg·g–1 fresh weight. -

Rapid Determination of Nutrient Concentrations in Hass Avocado Fruit by Vis/NIR Hyperspectral Imaging of Flesh Or Skin

remote sensing Article Rapid Determination of Nutrient Concentrations in Hass Avocado Fruit by Vis/NIR Hyperspectral Imaging of Flesh or Skin Wiebke Kämper 1,2,* , Stephen J. Trueman 1,2, Iman Tahmasbian 3 and Shahla Hosseini Bai 1 1 Environmental Futures Research Institute, School of Environment and Science, Griffith University, Nathan, QLD 4111, Australia; s.trueman@griffith.edu.au (S.J.T.); s.hosseini-bai@griffith.edu.au (S.H.B.) 2 Genecology Research Centre, University of the Sunshine Coast, Maroochydore DC, QLD 4558, Australia 3 Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Queensland Government, Toowoomba, QLD 4350, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: w.kaemper@griffith.edu.au Received: 26 August 2020; Accepted: 14 October 2020; Published: 17 October 2020 Abstract: Fatty acid composition and mineral nutrient concentrations can affect the nutritional and postharvest properties of fruit and so assessing the chemistry of fresh produce is important for guaranteeing consistent quality throughout the value chain. Current laboratory methods for assessing fruit quality are time-consuming and often destructive. Non-destructive technologies are emerging that predict fruit quality and can minimise postharvest losses, but it may be difficult to develop such technologies for fruit with thick skin. This study aimed to develop laboratory-based hyperspectral imaging methods (400–1000 nm) for predicting proportions of six fatty acids, ratios of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, and the concentrations of 14 mineral nutrients in Hass avocado fruit from 219 flesh and 194 skin images. Partial least squares regression (PLSR) models predicted the ratio of unsaturated to saturated fatty acids in avocado fruit from both flesh images (R2 = 0.79, ratio of prediction to deviation (RPD) = 2.06) and skin images (R2 = 0.62, RPD = 1.48). -

Summary Report: Whole Fresh Avocados

FY 2014 – 2016 Microbiological Sampling Assignment Summary Report: Whole Fresh Avocados Office of Compliance Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition December 2018 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................... 3 BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................................................................ 7 SAMPLE COLLECTION ............................................................................................................................................. 7 PATHOGEN FINDINGS .......................................................................................................................................... 10 Pathogen Findings: Salmonella ........................................................................................................................ 10 Pathogen Findings: Listeria monocytogenes (Pulp Samples) ............................................................................ 11 Pathogen Findings: Listeria monocytogenes (Skin Samples) ............................................................................ 11 Pathogen Findings: By Country of Origin ........................................................................................................ -

Avocado Intake, and Longitudinal Weight and Body Mass Index Changes in an Adult Cohort

nutrients Article Avocado Intake, and Longitudinal Weight and Body Mass Index Changes in an Adult Cohort Celine Heskey * , Keiji Oda and Joan Sabaté Center for Nutrition, Healthy Lifestyle and Disease Prevention, 24951 North Circle Drive, School of Public Health, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, CA 92350, USA; [email protected] (K.O.); [email protected] (J.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-909-558-1000 (ext. 47181) Received: 1 February 2019; Accepted: 19 March 2019; Published: 23 March 2019 Abstract: Avocados contain nutrients and bioactive compounds that may help reduce the risk of becoming overweight/obese. We prospectively examined the effect of habitual avocado intake on changes in weight and body mass index (BMI). In the Adventist Health Study (AHS-2), a longitudinal cohort (~55,407; mean age ~56 years; U.S. and Canada), avocado intake (standard serving size 32 g/day) was assessed by a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). Self-reported height and weight were collected at baseline. Self-reported follow-up weight was collected with follow-up questionnaires between four and 11 years after baseline. Using the generalized least squares (GLS) approach, we analyzed repeated measures of weight in relation to avocado intake. Marginal logistic regression analyses were used to calculate the odds of becoming overweight/obese, comparing low (>0 to <32 g/day) and high (≥32 g/day) avocado intake to non-consumers (reference). Avocado consumers who were normal weight at baseline, gained significantly less weight than non-consumers. The odds (OR (95% CI)) of becoming overweight/obese between baseline and follow-up was 0.93 (0.85, 1.01), and 0.85 (0.60, 1.19) for low and high avocado consumers, respectively. -

Propagation Experiments with Avocado, Mango, and Papaya

Proceedings of the AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR HORTICULTURAL SCIENCE 1933 30:382-386 Propagation Experiments with Avocado, Mango, and Papaya HAMILTON P. TRAUB and E. C. AUCHTER U. S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, D. C. During the past year several different investigations relative to the propagation of the avocado, mango and papaya have been conducted in Florida. In this preliminary report, the results of a few of the different experiments will be described. Germination media:—Avocado seeds of Gottfried (Mex.) during the summer season, and Shooter (Mex.) during the fall season; and Apple Mango seeds during the summer season, were germinated in 16 media contained in 4 x 18 x 24 cypress flats with drainage provided in the bottom. The eight basic materials and eight mixtures of these, in equal proportions in each case, tested were: 10-mesh charcoal, 6-mesh charcoal, pine sawdust, cypress sawdust, sand, fine sandy loam, carex peat, sphagnum peat, sand plus loam, carex peat plus sand, sphagnum peat plus sand, carex peat plus loam, sand plus coarse charcoal, loam plus coarse charcoal, cypress sawdust plus coarse charcoal, and carex peat plus sand plus coarse charcoal. During the rainy summer season, with relatively high temperature and an excess of moisture without watering, 10-mesh charcoal, and the mixture of carex peat plus sand plus charcoal proved most rapid, but for the drier, cooler fall season, when watering was necessary, the mixture of cypress sawdust plus charcoal was added to the list. During the rainy season the two charcoal media, sphagnum peat, sand plus charcoal, cypress sawdust plus charcoal, and carex peat plus sand plus charcoal gave the highest percentages of germination at the end of 6 to 7 weeks, but during the drier season the first three were displaced by carex peat plus sand, and sphagnum peat plus sand. -

'Hass' Avocado Fruit

New Zealand Avocado Growers’ Association Annual Research Report Vol 7: 97 - 102 CARBOHYDRATE STATUS INTRODUCTION OF LATE SEASON 'HASS' Maturity in avocado fruit is usually discussed in AVOCADO FRUIT terms of the dry matter or water content of the fruit flesh. The dry matter content of the fruit flesh is J. Burdon, N. Lallu, G. Haynes, P. Pidakala, P. Willcocks, correlated with the oil content (Lee et al., 1983) and D. Billing, K. McDermott, D. Voyle and H. Boldingh. is a useful measure of the minimum maturity HortResearch, Private Bag 92169, Auckland required for harvest based on eating quality of the Corresponding author: [email protected] ripe fruit. Dry matter is less useful for determining fruit maturity for fruit that are more advanced or are ABSTRACT over-mature (Hofman et al., 2000). Other compositional attributes including the In this study, changes in carbohydrate composition carbohydrate status of the fruit flesh may be during the late season maturation phase of 'Hass' potential markers of fruit maturity. Carbohydrates avocado fruit were determined for fruit harvested in have been researched recently as fruit attributes the 2005-6 and 2006-7 seasons. Fruit were that change during fruit development and a harvested fortnightly between December 2005 and question has been posed as to whether there is a April 2006 from three orchards and weekly link to fruit quality (Bertling and Bower, 2006). For between February and May 2007 from two carbohydrate status, the role of the 7-carbon sugar orchards. Carbohydrate was quantified as the fruit (C7) mannoheptulose and its sugar alcohol dry matter, soluble solids content (SSC), starch perseitol are of interest since they are the dominant c o n t e n t a n d t h e i n d i v i d u a l s u g a r s sugars present in avocado (Liu et al., 2002). -

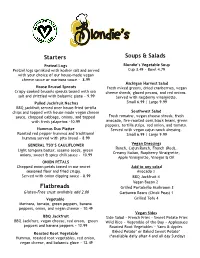

Starters Flatbreads Soups & Salads

Starters Soups & Salads Pretzel Logs Blondie’s Vegetable Soup Pretzel logs sprinkled with kosher salt and served Cup 3.49 ~ Bowl 4.79 with your choice of our house-made vegan cheese sauce or marinara sauce ~ 8.99 Michigan Harvest Salad House Brussel Sprouts Fresh mixed greens, dried cranberries, vegan Crispy cooked brussels sprouts tossed with sea cheese shreds, glazed pecans, and red onions. salt and drizzled with balsamic glaze ~ 9.99 Served with raspberry vinaigrette. Pulled Jackfruit Nachos Small 6.99 | Large 9.99 BBQ jackfruit served over house-fried tortilla chips and topped with house-made vegan cheese Southwest Salad sauce, chopped cabbage, onions, and topped Fresh romaine, vegan cheese shreds, fresh with fresh jalapeños ~10.99 avocado, fire-roasted corn,black beans, green peppers, tortilla strips, red onion, and tomato. Hummus Duo Platter Served with vegan cajun ranch dressing. Roasted red pepper hummus and traditional Small 6.99 | Large 9.99 hummus served with pita bread ~ 8.99 GENERAL TSO’S CAULIFLOWER Vegan Dressings Ranch, Cajun Ranch, French (Red), Light tempura batter, sesame seeds, green Creamy Italian, Raspberry Vinaigrette, onions, sweet & spicy chili sauce – 10.99 Apple Vinaigrette, Vinegar & Oil ONION PETALS Chopped onion petals tossed in our secret Add to any salad seasoned flour and fried crispy. Avocado 2 Served with onion dipping sauce – 8.99 BBQ Jackfruit 4 Vegan Bacon 2 Flatbreads Grilled Portobello Mushroom 3 Gluten-Free crust available add 2.00 Garbanzo Beans (Chick Peas) 1 Vegetable Grilled Tofu 4 Marinara, -

Avocado Production in California Patricia Lazicki, Daniel Geisseler and William R

Avocado Production in California Patricia Lazicki, Daniel Geisseler and William R. Horwath Background Avocados are native to Central America and the West Indies. While the Spanish were familiar with avocados, they did not include them in the mission gardens. The first recorded avocado tree in California was planted in 1856 by Thomas White of San Gabriel. The first commercial orchard was planted in 1908. In 1913 the variety ‘Fuerte’ was introduced. This became the first important commercial variety, due to its good taste and cold tolerance. Despite its short season and Figure 1: Area of bearing avocado trees in California since erratic bearing it remained the industry 1925 [4,5]. standard for several decades [3]. The black- skinned ‘Hass’ avocado was selected from a seedling grown by Robert Hass of La Habra in 1926. ‘Hass’ was a better bearer and had a longer season, but was initially rejected by consumers already familiar with the green-skinned ‘Fuerte’. However, by 1972 ‘Hass’ surpassed ‘Fuerte’ as the dominant variety, and as of 2012 accounted for about 95% of avocados grown in California [3]. By the early 1930s, California had begun to export avocados to Europe. Figure 2: California avocado production (total crop and Research into avocados’ nutritional total value) since 1925 [4,5]. benefits in the 1940s — and a shortage of [1,3] fats and oils created by World War II — in the early 1990s . The state’s crop lost over [5] contributed to an increased acceptance of the half its value between 1990 and 1993 (Fig. 2) . fruit [3]. However, acreage expansion from 1949 Aggressive marketing, combined with acreage to 1965 depressed markets and led to slightly reduction, revived the industry for the next [1,3] decreased plantings through the 1960s (Fig. -

Physico-Chemical, Morphological and Technological Properties of the Avocado (Persea Americana Mill

Ciência e Agrotecnologia, 44:e001420, 2020 Food Science and Technology http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1413-7054202044001420 eISSN 1981-1829 Physico-chemical, morphological and technological properties of the avocado (Persea americana Mill. cv. Hass) seed starch Propriedades físico-químicas, morfológicas e tecnológicas do amido do caroço de abacate (Persea americana Mill. cv. Hass) Jéssica Franco Freitas Macena1 , Joiciana Cardoso Arruda de Souza1, Geany Peruch Camilloto2 , Renato Souza Cruz2* 1Universidade Federal da Bahia/UFBA, Salvador, BA, Brasil 2Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana/UEFS, Feira de Santana, BA, Brasil *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received in January 17, 2020 and approved in April 14, 2020 ABSTRACT Avocado seeds (Persea americana Mill) are a byproduct of fruit processing and are considered a potential alternative source of starch. Starch is widely used as a functional ingredient in food systems, along with additives such as salt, sugars, acids and fats. This study aimed to perform the physicochemical, morphological and technological characterization of starch from avocado seeds and to evaluate the consistency of gels when salt, sugar, acid and fat are added. Extraction yield was 10.67% and final moisture 15.36%. The apparent amylose content (%) was higher than other cereal and tuber starches. XRD standards confirmed the presence of type B crystallinity, typical of fruits and tubers, with a crystallinity degree of 56.09%. The swelling power increased with increasing temperature (above 70 °C). Avocado seed starch (ASS) presented a syneresis rate of 42.5%. Viscoamylography showed that ASS is stable at high temperatures. TPA analysis showed that ASS gels with different additives and concentrations varied significantly (p<0.05) from the control sample, mainly in the hardness and gumminess profiles. -

Greensheet-March-1-2021.Pdf

Volume 37 Ι Issue 5 Ι March 1, 2021 IN THIS ISSUE, YOU’LL FIND: Nominations for Hass Avocado Board Now Open CAC Releases Updated 2021 Crop Volume and Harvest Projections COVID Vaccines Available for Agricultural Workers in San Diego County New Website Provides Employers with COVID-19 Compliance Assistance How Textural Stratification of Soil Impacts Irrigation Spring Is Ideal For ProGibb LV Plus® Application Point-of-Sale Data Reveals Marketing Program’s Success in Building Demand for Avocados Market Trends Crop Statistics Weather Outlook Calendar For a listing of industry events and dates for the coming year, please visit: http://www.californiaavocadogrowers.com/commission/industry-calendar CAC Finance Committee Web/Teleconference March 4 March 4 Time: 9:00am – 9:55am Location: Web/Teleconference CAC Board Web/Teleconference Meeting March 4 March 4 Time: 10:00am – 12:30pm Location: Web/Teleconference Nominations for Hass Avocado Board Now Open The Hass Avocado Board, comprised of 12 members, is now accepting nominations. HAB plays an important role in promoting consumption of Hass avocados across the United States. HAB board members attend four meetings a year and by sharing their expertise play an important decision-making role concerning HAB policies, research, promotional programs and direction. The term for new members and alternates begins November 1, 2021, with those newly elected being officially seated at the board meeting on December 1, 2021. HAB mailed board nomination announcements to all eligible producers and importers on March 1. The timeline for the remainder of the process is as follows: • March 30 — Deadline for receipt of nomination forms Page 1 of 13 • April 26 — Ballots mailed to producers and importers • May 24 — Deadline for receipt of ballots • June 7 — Nominations results announced by board with two nominees for each position in industry preference provided for consideration to the USDA Secretary of Agriculture Complete information is provided on the HAB website.