Contemporary Contemporary Kerala Ry Kerala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KSEB Junior Assistant Cashier 1996.Pmd

KSEB Junior Assistant/Cashier 1996 1. Who is the recipient of Nobel Prize 1998 for Literature? (a) Seamus Heaney (b) Salman Rushdie (c) Promodya Antora Toer (c) Fritj of Kapra (e) Saramago 2. One of the places where Total Solar Eclipse was visible on 24 October 1995 was Neem Ka Thana. Which State does this place belong to? (a) West Bengal (b) Rajasthan (c) Gujarat (d) Orissa (e) None of these 3. SDR is related to ———— (a) IMF (b) EEC (c) UNICEF (d) ILO (e) None of these 4. The Headquarters of ILO is at ———— (a) Brussels (b) the Hague (c) Geneva (d) Washington (e) None of these 5. Which of the following countries does not belong to OPEC? (a) Kuwait (b) Libya (c) Qatar (d) UAE (e) None of these 6. The Secretary General of the UNO at present is ———— (a) Dag Hammarskjold (b) Boutros Boutros Ghali (c) Kurt Waldheim (d) U Thant (e) Kofi Annan 7. The country expelled from the Commonwealth in 1995 was ———— (a) Nigeria (b) Zambia (c) Namibia (d) Algeria (e) None of these 8. The largest planet in the solar system is ———— (a) Saturn (b) Jupiter (c) Mercury (d) Mars (e) None of these 9. The first man-made satellite was launched into space by the Soviet Union in the year ———— (a) 1961 (b) 1959 (c) 1957 (d) 1962 (e) None of these 10. The first living being launched into space was a ———— (a) man (b) bird (c) monkey (d) dog (e) None of these 11. The longest night in the northern hemisphere is on ———— (a) 21 March (b) 21 June (c) 22 December (d) 23 September (e) None of these 12. -

Western Ghats & Sri Lanka Biodiversity Hotspot

Ecosystem Profile WESTERN GHATS & SRI LANKA BIODIVERSITY HOTSPOT WESTERN GHATS REGION FINAL VERSION MAY 2007 Prepared by: Kamal S. Bawa, Arundhati Das and Jagdish Krishnaswamy (Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology & the Environment - ATREE) K. Ullas Karanth, N. Samba Kumar and Madhu Rao (Wildlife Conservation Society) in collaboration with: Praveen Bhargav, Wildlife First K.N. Ganeshaiah, University of Agricultural Sciences Srinivas V., Foundation for Ecological Research, Advocacy and Learning incorporating contributions from: Narayani Barve, ATREE Sham Davande, ATREE Balanchandra Hegde, Sahyadri Wildlife and Forest Conservation Trust N.M. Ishwar, Wildlife Institute of India Zafar-ul Islam, Indian Bird Conservation Network Niren Jain, Kudremukh Wildlife Foundation Jayant Kulkarni, Envirosearch S. Lele, Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Environment & Development M.D. Madhusudan, Nature Conservation Foundation Nandita Mahadev, University of Agricultural Sciences Kiran M.C., ATREE Prachi Mehta, Envirosearch Divya Mudappa, Nature Conservation Foundation Seema Purshothaman, ATREE Roopali Raghavan, ATREE T. R. Shankar Raman, Nature Conservation Foundation Sharmishta Sarkar, ATREE Mohammed Irfan Ullah, ATREE and with the technical support of: Conservation International-Center for Applied Biodiversity Science Assisted by the following experts and contributors: Rauf Ali Gladwin Joseph Uma Shaanker Rene Borges R. Kannan B. Siddharthan Jake Brunner Ajith Kumar C.S. Silori ii Milind Bunyan M.S.R. Murthy Mewa Singh Ravi Chellam Venkat Narayana H. Sudarshan B.A. Daniel T.S. Nayar R. Sukumar Ranjit Daniels Rohan Pethiyagoda R. Vasudeva Soubadra Devy Narendra Prasad K. Vasudevan P. Dharma Rajan M.K. Prasad Muthu Velautham P.S. Easa Asad Rahmani Arun Venkatraman Madhav Gadgil S.N. Rai Siddharth Yadav T. Ganesh Pratim Roy Santosh George P.S. -

A Portrayal of People Essays on Visual Anthropology

A PORTRAYAL OF PEOPLE Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from Public.Resource.Org https://archive.org/details/portrayalofpeoplOOunse A PORTRAYAL OF PEOPLE Essays on Visual Anthropology in India Co-published by ANTHROPOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA INDIAN NATIONAL TRUST FOR ART AND CULTURAL HERITAGE INTACH 71, Lodhi Estate New Delhi-110 003 ANTHROPOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA West Block 2, Wing 6, First Floor R.K. Puram New Delhi 110 066. ©ASI, INTACH, 1987. © For individual contributions with authors. Printed at Indraprastha Press (CBT) 4 Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi 110002. CONTENTS Foreword v Introduction ix An Examination of the 1 Need and Potential for Visual Anthropology in India Rakhi Roy and Jayasinhji Jhala Anthropological Survey of 20 India and Visual Anthropology K.S. Singh History of Visual Anthropology 49 in India K.N. Sahay Perceptions of the Self and Other 75 in Visual Anthropology Rakhi Roy and Jayasinhji Jhala My Experiences as a Cameraman 99 in the Anthropological Survey Susanta K. Chattopadhyay The Vital Interface 114 Ashish Rajadhyaksha The Realistic Fictional Film: 127 How far from Visual Anthropology? Chidananda Das Gupta Phaniyamma and the Triumph 139 of Asceticism T.G. Vaidyanathan Images of Islam and Muslims 147 on Doordarshan Iqbal Masud Man in My Films 161 Mrinal Sen/Someshwar Bhowmick The Individual and Society 169 Adoor Gopalakrishnan/Madhavan Kutty Notes on Contributors 174 FOREWORD It has often been said that India lives in many centuries at the same time. The complex network of diversity that stretches across time and space has made India a paradise for anthropologists. -

Analysing Lee's Hypotheses of Migration in the Context of Malabar

International Journal of Research in Geography (IJRG) Volume 4, Issue 1, 2018, PP 1-8 ISSN 2454-8685 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-8685.0401001 www.arcjournals.org Analysing Lee’s Hypotheses of Migration in the Context of Malabar Migration: A Case Study of Taliparamba Block, Kannur District Surabhi Rani 1 Dept.of Geography, Kannur University Payyanur Campus, Edat. P.O ,Payyanur, Kannur, Kerala Abstract: Human Migration is considered as one of the important demographic process which has manifold effect on the society as well as to the individuals, apart from the other population dynamics of fertility and mortality. Several approaches dealing with migration has evolved the concepts related to the push and pull factors causing migration. Malabar Migration is a historical phenomenon of internal migration, in which massive exodus took place in the vast jungles of Malabar concentrating with similar socio-cultural-economic group of people. Various factors related to social, cultural, demographical and economical aspects initiated the migration from erstwhile Travancore to erstwhile Malabar district. The present preliminary study tries to focus over such factors associated with Malabar Migration in Taliparamba block of Kannur district (Kerala).This study is based on the primary survey of the study area and further supplemented with other secondary materials. Keywords: migration, push and pull factors, Travancore, Malabar 1. INTRODUCTION Human migration is one of the few truly interdisciplinary fields of research of social processes which has widespread consequences for both, individuals and the society. It is a sort of geographical or spatial mobility of people with change in their place of residence and socio-cultural environment. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Marxist Praxis: Communist Experience in Kerala: 1957-2011

MARXIST PRAXIS: COMMUNIST EXPERIENCE IN KERALA: 1957-2011 E.K. SANTHA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SIKKIM UNIVERSITY GANGTOK-737102 November 2016 To my Amma & Achan... ACKNOWLEDGEMENT At the outset, let me express my deep gratitude to Dr. Vijay Kumar Thangellapali for his guidance and supervision of my thesis. I acknowledge the help rendered by the staff of various libraries- Archives on Contemporary History, Jawaharlal Nehru University, C. Achutha Menon Study and Research Centre, Appan Thampuran Smaraka Vayanasala, AKG Centre for Research and Studies, and C Unniraja Smaraka Library. I express my gratitude to the staff at The Hindu archives and Vibha in particular for her immense help. I express my gratitude to people – belong to various shades of the Left - who shared their experience that gave me a lot of insights. I also acknowledge my long association with my teachers at Sree Kerala Varma College, Thrissur and my friends there. I express my gratitude to my friends, Deep, Granthana, Kachyo, Manu, Noorbanu, Rajworshi and Samten for sharing their thoughts and for being with me in difficult times. I specially thank Ugen for his kindness and he was always there to help; and Biplove for taking the trouble of going through the draft intensely and giving valuable comments. I thank my friends in the M.A. History (batch 2015-17) and MPhil/PhD scholars at the History Department, S.U for the fun we had together, notwithstanding the generation gap. I express my deep gratitude to my mother P.B. -

Download Download

Citizenship Discourse, Globalization, and Protest: A Postsocialist-Postcolonial Comparison1 David A. Kideckel, Central Connecticut State University Introduction: On postsocialist/colonial comparison Recent scholarship recognizes important commonalities in postsocialist and postcolonial experience. Both Moore (2001:114) and Chari and Verdery (2009: 11) discuss substantive parallels in postcolonial and postsocialist states. Such states emerge from common structural conditions deemphasizing local versus metropolitan culture (ibid: 13, Young 2003), are burdened with imbalanced, distorted economies (Bunce 1999, Humphrey 2002, Stark and Bruszt 1998), struggle with democratization (Ceuppens and Geschiere 2005, Heintz et al 2007), fall occasional prey to compensatory and muscular nationalisms (Appadurai 1996, 2006), and have troubled relations with past histories and compromised members (Borneman 1997, Comaroff and Comaroff 2003, Petryna 2002). Thus postsocialist and postcolonial state political and economic organization and principles of belonging are up for grabs with these uncertainties mapping onto principles and discourses of citizenship, i.e. the way individuals conceive of themselves in relation to their state and in other transnational relationships (Ong 1999), respond to changes in state life, and express themselves politically and culturally as members of society. Uncertain citizenship, contested histories, and distorted economies often subject postsocialist and postcolonial states to significant activism (Young 2003). This paper thus seeks to articulate activist practice with variations in the nature of citizenship conceptions and discourses, offering a window into postsocialist and postcolonial similarity and difference. Ethnographically, the essay compares protests and demonstrations in postcolonial Kerala state in southwest India2 and postsocialist east central European Romania. As part of their “post” heritages, both states are marked by outpourings of activist demand. -

The People's Biodiversity Registers Program Author(S): Madhav Gadgil, P

New Meanings for Old Knowledge: The People's Biodiversity Registers Program Author(s): Madhav Gadgil, P. R. Seshagiri Rao, G. Utkarsh, P. Pramod, Ashwini Chhatre, Members of the People's Biodiversity Initiative Source: Ecological Applications, Vol. 10, No. 5 (Oct., 2000), pp. 1307-1317 Published by: Ecological Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2641286 Accessed: 03/11/2010 16:21 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=esa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Ecological Society of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Ecological Applications. -

Download Brochure

Celebrating UNESCO Chair for 17 Human Rights, Democracy, Peace & Tolerance Years of Academic Excellence World Peace Centre (Alandi) Pune, India India's First School to Create Future Polical Leaders ELECTORAL Politics to FUNCTIONAL Politics We Make Common Man, Panchayat to Parliament 'a Leader' ! Political Leadership begins here... -Rahul V. Karad Your Pathway to a Great Career in Politics ! Two-Year MASTER'S PROGRAM IN POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND GOVERNMENT MPG Batch-17 (2021-23) UGC Approved Under The Aegis of mitsog.org I mitwpu.edu.in Seed Thought MIT School of Government (MIT-SOG) is dedicated to impart leadership training to the youth of India, desirous of making a CONTENTS career in politics and government. The School has the clear § Message by President, MIT World Peace University . 2 objective of creating a pool of ethical, spirited, committed and § Message by Principal Advisor and Chairman, Academic Advisory Board . 3 trained political leadership for the country by taking the § A Humble Tribute to 1st Chairman & Mentor, MIT-SOG . 4 aspirants through a program designed methodically. This § Message by Initiator . 5 exposes them to various governmental, political, social and § Messages by Vice-Chancellor and Advisor, MIT-WPU . 6 democratic processes, and infuses in them a sense of national § Messages by Academic Advisor and Associate Director, MIT-SOG . 7 pride, democratic values and leadership qualities. § Members of Academic Advisory Board MIT-SOG . 8 § Political Opportunities for Youth (Political Leadership diagram). 9 Rahul V. Karad § About MIT World Peace University . 10 Initiator, MIT-SOG § About MIT School of Government. 11 § Ladder of Leadership in Democracy . 13 § Why MIT School of Government. -

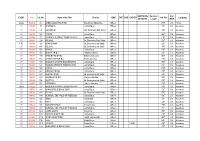

EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P

UMATIC/DG Duration/ Col./ EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P. B.) Man Mohan Mahapatra 06Reels HST Col. Oriya I. P. 1982-83 73 APAROOPA Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1985-86 201 AGNISNAAN DR. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1986-87 242 PAPORI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 252 HALODHIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 294 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 06Reels EST Col. Assamese F.O.I. 1985-86 429 AGANISNAAN Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 440 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 06Reels SST Col. Assamese I. P. 1989-90 450 BANANI Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 483 ADAJYA (P. B.) Satwana Bardoloi 05Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 494 RAAG BIRAG (P. B.) Bidyut Chakravarty 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 500 HASTIR KANYA(P. B.) Prabin Hazarika 03Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 509 HALODHIA CHORYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 522 HALODIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels FST Col. Assamese I. P. 1990-91 574 BANANI Jahnu Barua 12Reels HST Col. Assamese I. P. 1991-92 660 FIRINGOTI (P. B.) Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1992-93 692 SAROTHI (P. B.) Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 05Reels EST Col. -

With Special Implication to Gulf Migrants from Kerala

Vol 3, Number 9, September 2017 ISSN- 2454-3675 September 2017 Global Research Forum on Diaspora and Transnationalism33 Redrawing the contours of Diaspora representations: with special implication to Gulf migrants from Kerala Nimmi I GRFDT ResearchResearch Monograph 33 ,Monograph Vol 3, Number 9, Septermber Series 2017 1 GRFDT Research Monograph Series GRFDT brings out Research Monograph series every month since January 2015. The Research Mono- graph covers current researches on Diaspora and International Migration issues. All the papers pub- lished in this research Monograph series are peer reviewed. There is no restriction in free use of the material in full or parts. However user must duly acknowledge the source. Editorial Board Dr. Anjali Sahay Associate Professor, International Relations and Political Science at Gannon University, Pennsylvania, USA Dr. Ankur Datta Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, South Asian University, New Delhi Dr. Els van Dongen Assistant Professor, Nanyang Technological university, Singapore Dr. Evans Stephen Osabuohien Dept. of Economics and Development Studies, Covenant University, Nigeria Prof. Guofu LIU School of Law, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beijing Dr. Kumar Mahabir The University of Trinidad and Tobago, Corinth Teachers College, UTT Dr. M. Mahalingam Research Fellow, Centre For Policy Analysis, New Delhi Dr. Nandini C. Sen Associate Professor. Cluster Innovation Centre, University of Delhi, New Delhi Dr. Nayeem Sultana Associate Professor, Department of Development Studies, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh Dr. Ned Bertz Assistant Professor of History, University of Hawaii Dr. Raj Bourdouille Migration and Development Researcher, Centre for Refugee Studies, York University, Toronto, Canada Dr. Smita Tiwari Research Fellow, Indian Council of World Affairs, New Delhi Dr. -

427 to Survive Or to Flourish? Minority Rights

1 Working Paper 427 TO SURVIVE OR TO FLOURISH? MINORITY RIGHTS AND SYRIAN CHRISTIAN COMMUNITY ASSERTIONS IN 20TH CENTURY TRAVANCORE/KERALA J. Devika V. J. Varghese March 2010 2 Working Papers can be downloaded from the Centre’s website (www.cds.edu) 3 TO SURVIVE OR TO FLOURISH? MINORITY RIGHTS AND SYRIAN CHRISTIAN COMMUNITY ASSERTIONS IN 20TH CENTURY TRAVANCORE/KERALA J. Devika V. J. Varghese March 2010 Earlier versions of this paper have been presented in the conference on ‘Really Existing Secularisms’ at CSDS New Delhi, 10-12 April, 2009 and subsequently in an Open Seminar at CDS. The interventions of Rajeev Bhargava, D.L. Seth, Javed Alam, G. Gopakumar, M.A. Ommen and E.T. Mathew were indeed insightful. We also remain grateful to the anonymous referee for his useful comments. The usual disclaimers apply. 4 ABSTRACT The arrival of modernity not only constituted communities but also impelled them in competition against each other in Kerala. Modern politics of the state as a result is inextricably liked with intense community politics. The success of community politics for rights and resources varied across communities, so also strategies of assertion. This paper will focus on different instances of community assertions by the Syrian Christians in twentieth century Travancore/Kerala. The confrontation of the community with the Hindu state and the then Dewan in the 1930s, the ‘Liberation Struggle’ against the Communists during late 1950s and the anti-eviction movements of 1960s testifies to its lack of primordial adherences and openness to heterogeneous strategies as required by different historical circumstances. It moves freely from secular to non-secular, minoritarian to majoritarian and lawful to unlawful, with claims to a greater citizenship.