Arthur Kirby and the Last Years of Palestine Railways

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mediterranean Coast of Israel Is a New City,Now Under

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Theses and Major Papers Marine Affairs 12-1973 The editM erranean Coast of Israel: A Planner's Approach Sophia Professorsky University of Rhode Island Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/ma_etds Part of the Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, and the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Recommended Citation Professorsky, Sophia, "The eM diterranean Coast of Israel: A Planner's Approach" (1973). Theses and Major Papers. Paper 146. This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Marine Affairs at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Major Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. l~ .' t. ,." ,: .. , ~'!lB~'MEDI'1'ERRANEAN-GQAsT ~F.~"IsMt~·;.·(Al!~.oS:-A~PROACH ::".~~========= =~.~~=~~~==b======~~==~====~==.=~=====~ " ,. ••'. '. ,_ . .. ... ..p.... "".. ,j,] , . .;~ ; , ....: ./ :' ",., , " ",' '. 'a ". .... " ' ....:. ' ' .."~".,. :.' , v : ".'. , ~ . :)(A;R:t.::·AF'~~RS'· B~NMi'»APER. '..":. " i . .: '.'-. .: " ~ . : '. ". ..." '-" .~" ~-,.,. .... .., ''-~' ' -.... , . ", ~,~~~~"ed .' bYr. SOph1a,Ji~ofes.orsJcy .. " • "..' - 01 .,.-~ ~ ".··,::.,,;$~ld~~:' ·to,,:" f;~f.... ;)J~:Uexa~d.r . -". , , . ., .."• '! , :.. '> ...; • I ~:'::':":" '. ~ ... : .....1. ' ..~fn··tr8Jti~:·'btt·,~e~Mar1ne.~a1~S·~r~~. ", .:' ~ ~ ": ",~', "-". ~_"." ,' ~~. ;.,·;·X;'::/: u-=" .. _ " -. • ',. ,~,At:·;t.he ,un:lvers:U:~; tif Rh~:<:rs1..J\d. ~ "~.; ~' ~.. ~,- -~ !:).~ ~~~ ~,: ~:, .~ ~ ~< .~ . " . -, -. ... ... ... ... , •• : ·~·J;t.1l9ston.l~~;&:I( .. t)eceiDber; 1~73.• ". .:. ' -.. /~ NOTES, ===== 1. Prior to readinq this paper, please study the map of the country (located in the back-eover pocket), in order to get acquain:t.ed with names and locations of sites mentioned here thereafter. 2.- No ~eqaJ. aspects were introduced in this essay since r - _.-~ 1 lack the professional background for feedinq in tbe information. -

Tracks the Monthly Magazine of the Inter City Railway Society

Tracks the monthly magazine of the Inter City Railway Society Volume 40 No.7 July 2012 Inter City Railway Society founded 1973 www.icrs.org.uk The content of the magazine is the copyright of the Society No part of this magazine may be reproduced without prior permission of the copyright holder President: Simon Mutten (01603 715701) Coppercoin, 12 Blofield Corner Rd, Blofield, Norwich, Norfolk NR13 4RT Chairman: Carl Watson - [email protected] (07403 040533) 14, Partridge Gardens, Waterlooville, Hampshire PO8 9XG Treasurer: Peter Britcliffe - [email protected] (01429 234180) 9 Voltigeur Drive, Hart, Hartlepool TS27 3BS Membership Secretary: Trevor Roots - [email protected] (01466 760724) (07765 337700) Mill of Botary, Cairnie, Huntly, Aberdeenshire AB54 4UD Secretary: Stuart Moore - [email protected] (01603 714735) 64 Blofield Corner Rd, Blofield, Norwich, Norfolk NR13 4SA Magazine: Editorial Manager: Trevor Roots - [email protected] details as above Editorial Team: Sightings: James Holloway - [email protected] (0121 744 2351) 246 Longmore Road, Shirley, Solihull B90 3ES Traffic News: John Barton - [email protected] (0121 770 2205) 46, Arbor Way, Chelmsley Wood, Birmingham B37 7LD Website: Website Manager: Mark Richards - [email protected] 7 Parkside, Furzton, Milton Keynes, Bucks. MK4 1BX Yahoo Administrator: Steve Revill Books: Publications Manager: Carl Watson - [email protected] details as above Publications Team: Combine & Individual / Irish: Carl Watson - [email protected] Pocket Book: Carl Watson / Trevor Roots - [email protected] Wagons: Scott Yeates - [email protected] Name Directory: Eddie Rathmill / Trevor Roots - [email protected] USF: Scott Yeates / Carl Watson / Trevor Roots - [email protected] Contents: Officials Contact List .....................................2 Traffic and Traction News................ -

MIDDLE EAST, NORTH AFRICA China, Russia and Iran Seek to Revive Syrian Railways

MIDDLE EAST, NORTH AFRICA China, Russia and Iran Seek to Revive Syrian Railways OE Watch Commentary: In late November, the Syrian Ministry of Transport announced a major “…China’s ownership of railways lines, in addition to its signing plan to repair, update and expand Syria’s railway of a 2017 agreement with Syria to use the Lattakia Port and system. As detailed in the accompanying excerpt from the Syrian government daily al-Thawra, the maritime transport means that China will own the country…” plan includes completing an earlier project to connect Deir ez-Zor and Albu Kamal, along the border with Iraq’s al-Anbar Province. It also calls for a new line across the Syrian desert, connecting Homs to Deir ez-Zor. Along with helping jump-start the domestic economy, an effective rail network would allow Syria to leverage is strategic location, at the crossroads of historical east-west and north-south trade routes. The accompanying passage from the Syrian opposition news source Enab Baladi highlights the importance of Chinese investment to Syrian reconstruction efforts in general and the railway sector in particular. It cites a Syrian researcher who hints at extensive Chinese involvement in the future ownership of the Syrian rail system, something that, combined with a 2017 agreement allowing China to use the Lattakia Port, means that China will “own the country.” Russia is also involved in revamping the Syrian rail network, and the article notes that Russia’s UralVagonZavod will be providing new railway cars to Syria starting next year. Syria’s planned railroad extension along the Euphrates from Deir ez-Zor to the Iraqi border dates from before the war. -

47 – Your Virtual Visit – 10 Lh Trophy

YOUR VIRTUAL VISIT - 47 TO THE AUSTRALIAN ARMY MUSEUM OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA Throughout 2021, the Virtual Visit series will be continuing to present interesting features from the Museum’s collection and their background stories. The Australian Army Museum of Western Australia is now open four days per week, Wednesday through Friday plus Sunday. Current COVID19 protocols including contact tracing apply. 10 Light Horse Trophy Gun The Gun Is Captured The series of actions designated the Third Battle of Gaza was fought in late October -early November 1917 between British and Ottoman forces during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign. The Battle came after the British Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) victory at the Battle of Beersheba on 31 October had ended the stalemate in Southern Palestine. The fighting marked the launch of Southern Palestine Offensive, By 10 November, the Gaza-to-Beersheba line had been broken and the Ottoman Army began to withdraw. The 10th Australian Light Horse Regiment was part of the pursuit force trying to cut off the retiring Ottomans. Advancing forces were stopped by a strong rear guard of Turkish, Austrian and German artillery, infantry and machine guns on a ridge of high ground south of Huj, a village 15 km north east of Gaza. The defensive position was overcome late on 8 November, at high cost, by a cavalry charge by the Worcestershire and Warwickshire Yeomanry. 1 Exploitation by the 10th Light Horse on 9 November captured several more artillery pieces which were marked “Captured by 10 LH” This particular gun, No 3120, K26, was captured by C Troop, commanded by Lt FJ MacGregor, MC of C Squadron. -

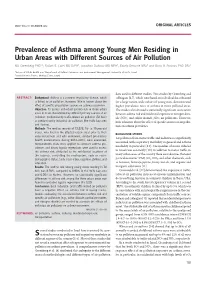

Prevalence of Asthma Among Young Men Residing in Urban Areas with Different Sources of Air Pollution Nili Greenberg Phd1,3, Rafael S

,0$-ǯ92/21ǯ'(&(0%(52019 ORIGINAL ARTICLES Prevalence of Asthma among Young Men Residing in Urban Areas with Different Sources of Air Pollution Nili Greenberg PhD1,3, Rafael S. Carel MD DrPH1, Jonathan Dubnov MD MPH1, Estela Derazne MSc3 and Boris A. Portnov PhD DSc2 1School of Public Health and 2Department of Natural Resources and Environment Management, University of Haifa, Israel 3Israeli Defense Forces, Medical Corps, Israel data used in different studies. Two studies by Greenberg and ABSTRACT: Background: Asthma is a common respiratory disease, which colleagues [6,7], which were based on individual data obtained is linked to air pollution. However, little is known about the for a large nation-wide cohort of young men, demonstrated effect of specific air pollution sources on asthma occurrence. higher prevalence rates of asthma in more polluted areas. Objective: To assess individual asthma risk in three urban The studies also showed a statistically significant association areas in Israel characterized by different primary sources of air between asthma risk and residential exposure to nitrogen diox- pollution: predominantly traffic-related air pollution (Tel Aviv) ide (NO2) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) air pollutants. However, or predominantly industrial air pollution (the Haifa bay area little is known about the effect of specific sources of air pollu- and Hadera). tion on asthma prevalence. Methods: The medical records of 13,875, 16- to 19-year-old males, who lived in the affected urban areas prior to their BACKGROUND STUDIES army recruitment and who underwent standard pre-military Air pollution from motor traffic and industries is significantly health examinations during 2012–2014, were examined. -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

Full Bibliography of Titles and Categories in One Handy PDF

Updated 21 June 2019 Full bibliography of titles and categories in one handy PDF. See also the reading list on Older Palestine History Nahla Abdo Captive Revolution : Palestinian Women’s Anti-Colonial Struggle within the Israeli Prison System (Pluto Press, 2014). Both a story of present detainees and the historical Socialist struggle throughout the region. Women in Israel : Race, Gender and Citizenship (Zed Books, 2011) Women and Poverty in the OPT (? – 2007) Nahla Abdo-Zubi, Heather Montgomery & Ronit Lentin Women and the Politics of Military Confrontation : Palestinian and Israeli Gendered Narratives of Diclocation (New York City : Berghahn Books, 2002) Nahla Abdo, Rita Giacaman, Eileen Kuttab & Valentine M. Moghadam Gender and Development (Birzeit University Women’s Studies Department, 1995) Stéphanie Latte Abdallah (French Institute of the Near East) & Cédric Parizot (Aix-Marseille University), editors Israelis and Palestinians in the Shadows of the Wall : Spaces of Separation and Occupation (Ashgate, 2015) – originally published in French, Paris : MMSH, 2011. Contents : Shira Havkin : Geographies of Occupation – Outsourcing the checkpoints – when military occupation encounters neoliberalism / Stéphanie Latte Abdallah : Denial of borders: the Prison Web and the management of Palestinian political prisoners after the Oslo Accords (1993-2013) / Emilio Dabed : Constitutionalism in colonial context – the Palestinian basic law as a metaphoric representation of Palestinian politics (1993-2007) / Ariel Handel : What are we talking about when -

British Rail Class 40

Peterborough 92016 British Rail Class 40 Manufacturer: Mark’s Trains & Wickness Models Project number: MW40-SSv1-RD Project version: V5 - Airport/Christmas/Diesel Depot/Farm/ Grand Station/Hedgerow/London/Market/Seascape/Steam Depot/ Urban Station/Special Locomotive: BR Class 40 Power type: Diesel-Electric Builder: English Electric at Vulcan Foundry & Robert Stephenson & Hawthorns Build date: 1958 - 1962 Total produced: 200 DCC Address: 3 Decoder type: ESU LokSound v5, Micro, L & XL CV63 main volume: 120 default (max 192) Speakers supported: 4 - 32 Ohms impedance, 3 Watt power maximum Volume CV’s column: Relevant CV’s to adjust individual sound volumes. Volume values column: Default volume setting for relevant sound CV’s. Before changing volume settings CV32 must be set to 1, and returned to 0 when finished. Failing to do so will inadvertently alter function settings. Fn Function Volume Volume Fn Function Volume Volume Key CV’s Value Key CV’s Value F0 Running Lights F15 Automatic Coupler 363 128 F1 Startup / Shutdown (Multi Start) 259 128 F16 Compressor 371 128 F2 Horn 283 128 F17 Cooling Fan 379 128 F3 No1 Cab Lights F18 Soundscape 387 128 F4 No2 Cab Lights F19 Sanding Valve 395 128 F5 Tail Lights Enable / Disable F20 Spirax Valve 403 128 F6 Brake Key 291 128 F21 Shunting Mode F7 Emergency Brake 299 128 F22 Drive Hold / Coast F8 Curve Squeal 307 128 F23 Heavy Load F9 Switch Flange 315 128 F24 AWS / Fire Bell Test 411 128 F10 Rail Clank 323 128 F25 Smoke Generator F11 Rail Noise 331 128 F26 Volume Control F12 Guard’s Whistle 339 128 F27 Disable Brake Squeal Sounds F13 Station Announcements 347 128 F28 Fade Out Sounds F14 Cab Doors Open / Close 355 128 Thank you for purchasing a MarWick Soundscape with RealDrive sound decoder. -

The Israel/Palestine Question

THE ISRAEL/PALESTINE QUESTION The Israel/Palestine Question assimilates diverse interpretations of the origins of the Middle East conflict with emphasis on the fight for Palestine and its religious and political roots. Drawing largely on scholarly debates in Israel during the last two decades, which have become known as ‘historical revisionism’, the collection presents the most recent developments in the historiography of the Arab-Israeli conflict and a critical reassessment of Israel’s past. The volume commences with an overview of Palestinian history and the origins of modern Palestine, and includes essays on the early Zionist settlement, Mandatory Palestine, the 1948 war, international influences on the conflict and the Intifada. Ilan Pappé is Professor at Haifa University, Israel. His previous books include Britain and the Arab-Israeli Conflict (1988), The Making of the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1947–51 (1994) and A History of Modern Palestine and Israel (forthcoming). Rewriting Histories focuses on historical themes where standard conclusions are facing a major challenge. Each book presents 8 to 10 papers (edited and annotated where necessary) at the forefront of current research and interpretation, offering students an accessible way to engage with contemporary debates. Series editor Jack R.Censer is Professor of History at George Mason University. REWRITING HISTORIES Series editor: Jack R.Censer Already published THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION AND WORK IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY EUROPE Edited by Lenard R.Berlanstein SOCIETY AND CULTURE IN THE -

Chapter 1 Outline of the Syrian Arab Republic

PART I THE PRESENT SITUATION AND MAJOR ISSUES Chapter 1 Outline of the Syrian Arab Republic The Master Plan Study on the Development of Syrian Railways Chapter 1 Chapter 1 Outline of the Syrian Arab Republic 1.1 Background (1) Location The Syrian Arab Republic is located between 32 to 37 degrees of the north latitude in the northern part of the Arabian penisula. It lies on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, bounded by Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Palestine and Jordan from the south and by Lebanon and the Mediterannean Sea to the west. The total land area of the country is 185,180 km2. (2) History The modern state of Syria was established only in 1946. However archaeologists have unearthed evidence of habitation dating back to 5000 B.C. Furthermore many archaeolo- gists consider Damascus to be the world’s oldest continuously inhabited city. The Egyptians, Babylonians, Hittites, Chaldeans and Persians have successively ruled an- cient Syria. It became a part of the Greek empire in 333 B.C., and a province of the Ro- man empire from 64 B.C. to 400 A.D. Remains of the famous Roman roads are still ob- served in Syria attesting to that country’s importance as a transport hub for the empire. Syria fell under the Byzantine Empire up to the 7th century when it became a part of the Arab and Islamic nation. From the 16th century Syria fell under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. At that time Syria was part of the Sham region, which roughly covered the present countries of Syria, Leba- non, and parts of Palestine and Jordan. -

1 a New Age of Steam?

A new age of steam? The Tua Valley Line, Portugal - Experience and Examples from the Technological Heritage Operations and Preserved Railways of Britain. Dr Dominic Fontana Department of Geography, University of Portsmouth, United Kingdom [email protected] The railways of Portugal are well known to a global community of steam enthusiasts, many of whom used to visit the country specifically to experience and photograph the last days of steam traction until as late as the 1980s. The narrow gauge lines north of the Douro River, and the Tua Valley line in particular, were considered as very special railways. Their outstanding combination of narrow gauge steam traction, relatively long runs of track and extraordinarily beautiful landscapes, made for a magical railway experience. In the 1980s steam was replaced with diesel traction and although there are now regular but infrequent steam hauled tourist trains on the Douro Valley line, there are currently very limited opportunities for people to recapture this experience. Portugal has several railway museums including the excellent National Railway Museum in Entroncamento, but these present static displays rather than “live” steam and many railway enthusiasts consider this to be a poor substitute for the “real” thing where steam locomotives are operating in steam, within a fully-fledged railway environment. 0189 2-8-4T Henschel 1925 Mallet locomotive at Regua. 1 Portugal possesses over 100 redundant steam locomotives (Bailey, 2013) dispersed in yards around its national railway network, some of them remain potentially usable and many are certainly restorable to full operating condition. Portugal also possesses track and routes, which have been recently closed to passenger and freight traffic. -

Report- the Large Cities at a Glance- Compendium of Maps, ICBS

Table of Contents Israeli Association for Cartography and Geographic Information Systems • About……………………………………………………………………………………….………….. 1 • Activities in Israel…………………………………………………………………..………..…….2 • Participation in ICA events……………………………………………………………..………5 Governmental Agencies • The Survey of Israel……………………………………………………………………..………..8 • Central Bureau of Statistics………………………………………………………..………..18 Map Libraries and Private Collectors National Library • Eran Laor Cartographic Collection- National Library of Israel………………..23 Academic Collections • Bloomfield Library for the Humanities and Social Sciences -Hebrew University in Jerusalem- Map Library and Geography Department……...25 • Tel Aviv University Geography Library………………………………………………….28 • Tel Hai Historical Map Archive- Tel Hai Academic College…………………...30 • Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi Map Archive………………………………………………………..…..31 • Younes & Soraya Nazarian Library- Map Collection, University of Haifa.33 Private Collectors • Bar Stav Collection of Ancient Maps of the Holy Land………………………….34 Private Sector • Ad-Or- Mapping the Old City of Jerusalem………………………………………….35 • Amud Anan Online Geo-Encyclopedia………………………………………………….36 • Avigdor Orgad Maps…………………………………………………………………………….37 • Blushtein Mapot Veod L.T.D. ……………………………………………………………….38 • Bonus-Yavne Publishing …………………………………………………………………….39 • GeoCartography Knowledge Group………………………………………………………40 • Israel Hiking and Biking Map ……………………………………………………………….42 • Mapa ………………………………………………………………………………………………..43 • Mind the Map ……………………………………………………………………………………..46 • Soffer