Ambivalent Ghosts: the Manifestation of the Supernatural in Ruth Rendell’S Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ruth Rendell and Barbara Vine – Family Matters', Contemporary Women's Writing, 11 (1), Pp

Peters, F. (2017) 'Ruth Rendell and Barbara Vine – family matters', Contemporary Women's Writing, 11 (1), pp. 31-47. This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in Contemporary Women’s Writing following peer review. The version of record is available online at: http://doi.org/10.1093/cww/vpw029 ResearchSPAce http://researchspace.bathspa.ac.uk/ This pre-published version is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Your access and use of this document is based on your acceptance of the ResearchSPAce Metadata and Data Policies, as well as applicable law:-https:// researchspace.bathspa.ac.uk/policies.html Unless you accept the terms of these Policies in full, you do not have permission to download this document. This cover sheet may not be removed from the document. Please scroll down to view the document. Ruth Rendell and Barbara Vine – Family Matters Fiona Peters Bath Spa University, UK [email protected] This article traces themes and preoccupations that work across Ruth Rendell’s work, writing both as Rendell and also as Barbara Vine. It investigates the ways in which the use of a pseudonym allows her to delve deeper into areas that she also explores as Rendell – the dysfunctional family and heredity, both in relation to physical disease and the fruitless search for origins, the latter discussed by her through the lens of Freudian psychoanalysis. Ruth Rendell was one of the most prolific British crime fiction writers of the twentieth century, continuing to produce work right up until her death in May 2015, her final posthumous novel Dark Corners being published in October of that year. -

The Thief Ruth Rendell

The Thief by Ruth Rendell The Thief Ruth Rendell 1 The Thief by Ruth Rendell Contents Briefly about the book 3 Information about Ruth Rendell 4 Crime writers 5 The characters 7 Why did the author do that? 9 Extract from Chapter 1 11 Further development 12 More Reading 13 Adult Core Curriculum References 14 Acknowledgement The learning materials to accompany the Quick Reads publications have been produced as part of The Vital Link’s Reading for Pleasure campaign, funded by the Department for Education and Skills and in co-operation with World Book Day. Our thanks go to the writing and editorial team of Nancy Gidley, Kay Jackaman and Moreen Mowforth. www.vitallink.org.uk 2 The Thief by Ruth Rendell Blurb Stealing things from people who upset her was something Polly did… but she could never have imagined it could have such terrifying results. Synopsis At first, after she takes his luggage off the Stealing and deceit were a way of life for Polly. trolley, she feels relief and joy: she has got her But when she meets and falls in love with Alex, revenge. However, her action leads to a series her life changes. Because he loves her and of events that take her into a world of fear and trusts hers, he believes her. And because she deception. In the end, they destroy her new life loves him, she wants to be truthful with him. with Alex. Because she is happy, she also finds that people don’t hurt her and she no longer needs This gripping story is told from Polly’s point of to take things from them. -

Ruth Rendell/Barbara Vine: Racial Otherness and Conservative Englishness

SBORNJK PRACI FILOZOFICKE FAKULTY BRNENSKE UNIVERZITY STUDIA MINORA FACULTATIS PHILOSOPHICAE UNIVERSITAT1S BRUNENSIS S 9,2003 — BRNO STUDIES IN ENGLISH 29 LIDIA KYZLINKOVA RUTH RENDELL/BARBARA VINE: RACIAL OTHERNESS AND CONSERVATIVE ENGLISHNESS Motto: 'What a pity it is, from the social historian's point of view, that there was no Ronald Knox in the monastery of the Venerable Bede; no Dorothy L. Sayers looking over Holinshed's shoulder while he white washed theTudors...' (Watson 1979: 2) It has generally been accepted that British mystery writers tend to accumulate a surprising amount of accurate information about everyday life since plausibil ity as much as fantasy is required to make their popular and prevailingly domes tic texts effectively thrilling and credible at the same time. In their work one therefore encounters multiple discourses concerning the meanings and represen tations gathered around the dominant issues of Englishness, race and class, in relation to the social reality of a specific public. The attractiveness of the narra tives may also lie in the fact that they raise significant and urgent questions about contemporary cultural identities and values against the background of a fictitious, romantic, and frequently gruesome world. Although it is a myth that classic detective fiction, with its stress on the puzzle value entirely avoids social issues, it is no fallacy that some of today's crime fiction which stems from it makes the social situation the very core of the plot. Ruth Rendell is viewed as one of the main representatives of the British psy chological crime novel today, however, apart from her interest in the individual characters' psyches she purposefully covers a number of fundamental social phenomena existing in contemporary Britain. -

Cassette Books, CMLS,P.O

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 319 210 EC 230 900 TITLE Cassette ,looks. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. PUB DATE 8E) NOTE 422p. AVAILABLE FROMCassette Books, CMLS,P.O. Box 9150, M(tabourne, FL 32902-9150. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) --- Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adults; *Audiotape Recordings; *Blindness; Books; *Physical Disabilities; Secondary Education; *Talking Books ABSTRACT This catalog lists cassette books produced by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped during 1989. Books are listed alphabetically within subject categories ander nonfiction and fiction headings. Nonfiction categories include: animals and wildlife, the arts, bestsellers, biography, blindness and physical handicaps, business andeconomics, career and job training, communication arts, consumerism, cooking and food, crime, diet and nutrition, education, government and politics, hobbies, humor, journalism and the media, literature, marriage and family, medicine and health, music, occult, philosophy, poetry, psychology, religion and inspiration, science and technology, social science, space, sports and recreation, stage and screen, traveland adventure, United States history, war, the West, women, and world history. Fiction categories includer adventure, bestsellers, classics, contemporary fiction, detective and mystery, espionage, family, fantasy, gothic, historical fiction, -

Murder Being Once Done: (A Wexford Case) Free

FREE MURDER BEING ONCE DONE: (A WEXFORD CASE) PDF Ruth Rendell | 272 pages | 01 Jul 2011 | Cornerstone | 9780099534860 | English | London, United Kingdom "Ruth Rendell Mysteries" Murder Being Once Done: Part One (TV Episode ) - IMDb Look Inside. A young girl is murdered in a cemetery. A compelling story of mysterious identity and untimely death, Murder Being Once Done is Rendell at her most sublime. For the canny, tireless, and unflappable policeman is an unblinking observer of human nature, whose study has taught him that under certain circumstances the most unlikely people are capable of the most appalling crimes. Since that first novel, Ruth Rendell has also demonstrated a keen fascination with the collision between society and the individual, particularly where circumstances drive the individual to behaviour that society Murder Being Once Done: (A Wexford Case) as somehow abnormal. Stable structures have only limited interest; what is gripping is where things start to fall apart, and that is the area where Ruth Rendell excels. Never content with mere description, she illuminates the human condition in a style that is invariably clear and compelling. Although she started with that most classic of English forms, the police procedural, she transformed it both with her psychological insights and her concern with society. She never descends to polemic, yet the picture she has painted of British society since the mid-Sixties is often far from neutral. It is clear that many things she sees make Ruth Rendell angry or despair, but her responses are always tempered through the filter of her characters; she always shows, never tells. -

Item More Personal, More Unique, And, Therefore More Representative of the Experience of the Book Itself

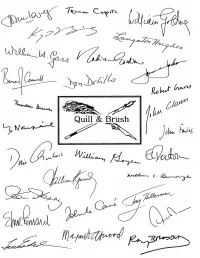

Q&B Quill & Brush (301) 874-3200 Fax: (301)874-0824 E-mail: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.qbbooks.com A dear friend of ours, who is herself an author, once asked, “But why do these people want me to sign their books?” I didn’t have a ready answer, but have reflected on the question ever since. Why Signed Books? Reading is pure pleasure, and we tend to develop affection for the people who bring us such pleasure. Even when we discuss books for a living, or in a book club, or with our spouses or co- workers, reading is still a very personal, solo pursuit. For most collectors, a signature in a book is one way to make a mass-produced item more personal, more unique, and, therefore more representative of the experience of the book itself. Few of us have the opportunity to meet the authors we love face-to-face, but a book signed by an author is often the next best thing—it brings us that much closer to the author, proof positive that they have held it in their own hands. Of course, for others, there is a cost analysis, a running thought-process that goes something like this: “If I’m going to invest in a book, I might as well buy a first edition, and if I’m going to invest in a first edition, I might as well buy a signed copy.” In other words we want the best possible copy—if nothing else, it is at least one way to hedge the bet that the book will go up in value, or, nowadays, retain its value. -

This Is a Peer-Reviewed Manuscript Version. the Final Version Is Published in Contemporary Women’S Writing with the Following Citation: Schnabel, Jennifer

1 This is a peer-reviewed manuscript version. The final version is published in Contemporary Women’s Writing with the following citation: Schnabel, Jennifer. "Realistic Man, Fantasy Policeman: The Longevity of Ruth Rendell’s Reginald Wexford." Contemporary Women's Writing 11.1 (2017): 102-120. https://doi.org/10.1093/cww/vpw044 Realistic Man, Fantasy Policeman: The Longevity of Ruth Rendell’s Reginald Wexford Ruth Rendell first introduced Chief Inspector Reginald Wexford in From Doon with Death in 1964; we last see him 49 years later in No Man’s Nightingale. Rendell develops the protagonist in her detective series, which includes 24 novels and five short stories, by adapting the conventions and tropes of the detective and police procedural genres set forth by her predecessors like Georges Simenon, Dorothy Sayers, and Ed McBain. However, while her detectives operate within the framework of the fictional Kingsmarkham police department, Rendell did not stifle Wexford with mundane bureaucratic constraints. Instead, she focused on presenting a realistic man with idiosyncrasies, shortcomings, and fears, as well as a character who adapts to the changing social and cultural environment alongside the reading public. Rendell has called Wexford “a fantasy policeman in a fantasy world,” using investigative methods which do not always adhere to standard police procedures (Salwak 87). As a result, forensic details are also largely missing from her narratives, such as in-depth descriptions of autopsies, lab processes, and coroner reports found in other contemporary crime novels and popular television programs. She said, “The wonder is that thousands of readers (including policemen!) seem to like it this way” (87). -

Gothic Elements in Selected Crime Novels by Ruth Rendell

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jana Mártonová The Gothic in Some Rendell Novels and its Protagonists Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Lidia Kyzlinková, CSc., M.Litt. 2014 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author‟s signature I would like to thank my supervisor, PhDr. Lidia Kyzlinková, CSc., M.Litt., for her valuable advice, patience and constant support. Thank you for all the help you gave me. I would also like to thank my family, Michal, Libor and Emina, for their infinite love and support they have provided me with. Thank you for being such beautiful people. Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 5 2. Background to Ruth Rendell ....................................................................................... 7 2.1 Life and Work ................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 On the Genre of Crime Fiction ...................................................................................... 11 2.3 Defining the Gothic ......................................................................................................... 21 3. Gothic elements in selected novels by Ruth Rendell ................................................. 25 3.1 Hero Figures -

Psychological Thrillers

Psychological Thrillers Alexander, Gary Blanchard, Alice 9. One Shot Blood Sacrifice Darkness Peering 10. The Hard Way Anscombe, Roderick The Breathtaker 11. Bad Luck and Trouble Paul Lucas Blauner, Peter 12. Nothing to Lose 1. The Interview Room The Intruder 13. Gone Tomorrow 2. Virgin Lies The Last Good Day 14. 61 Hours Anthony, Sterling Slipping into Darkness 15. Worth Dying For Cookie Cutter Bollen, Christopher 16. The Affair Archer, Jeffrey The Destroyers 17. A Wanted Man A Prisoner of Birth Bolton, S.J. 18. Never Go Back Baldacci, David Little Black Lies 19. Personal Last Man Standing Lacey Flint 20. Make Me Amos Decker 1. Now You See Me 21. Night School 1. Memory Man 2. Dead Scared 22. The Midnight Line 2. The Last Mile 3. Lost 23. Past Tense 3. The Fix 4. A Dark and Twisted Tide 24. Blue Moon 4. The Fallen Bonansinga, Jay R. 25. The Sentinel 5. Redemption Head Case 26. Better Off Dead 6. Walk the Wire Brundage, Elizabeth No Middle Name Atlee Pine The Doctor’s Wife Clark, Mary Higgins 1. Long Road to Mercy Burke, Alafair All Through the Night 2. A Minute to Midnight The Wife Before I Say Good-Bye Sean King & Michelle Maxwell Burke, Jan I’ll Walk Alone 1. Split Second Irene Kelly I’ve Got My Eyes on You 2. Hour Game 1. Goodnight, Irene Kiss the Girls and Make Them Cry 3. Simple Genius 2. Sweet Dreams, Irene The Melody Lingers On 4. First Family 3. Dear Irene Moonlight Becomes You 5. The Sixth Man 4. -

Illiteracy: the Ultimate Crime

ILLITERACY: THE ULTIMATE CRIME Ana de Brito Politecnico do Porto, Portugal The iss ue of reading ha s a privileged positi on in Ruth's Rendell's novels. In several, the uses of reading and its effects are disc ussed in some detail. But so are the uses of not reading and the non-read ers. The non-readers in Rendell's novels also have a special position . The murderer in The Hou se of Stairs is a non-reader but even so she is influenced by w hat other peopl e read. Non-readers often share the view that reading is an tisocial or that it is difficult to und er stand th e fascination that book s, those "small, flattish boxes"l have for their read ers. But Burd en is the most notoriou s non -reader w ho co mes to mind. His evolu tio n is ske tched throughout the Inspector Wexford mysteries. In From Doom with Death (1964) he thinks that it is not healthy to read, but Wexford lends him The Oxford Book of Victorian Verse for his bedtime reading, and the effects on his turn of phrase are immediate: 'I suppose the others could have been just-well , playthings as it we re, and Mrs. P. a life-long love.' 'Christ!', Wexford roared . 'I should never have let you read that book. Playthings, life-long love! You make me puke' (p. 125). In the 1970 novel A Cuiltlj Thing Surprised, Burden still feels embarrassed by his superior's "ted ious bookishness", and knows th e difference between fiction and real life.Pro us tia n or Shakespearean references are lost on Burden in No More Dying Fragmentos vol. -

Английский Язык Extra Reading Course

К.А. АСТАХОВА, Р.Х. ДМИТРИЕВА, Е.А. ИВАНОВА, В.В. МОШКОВИЧ, Н.В. ПОДКОВЫРОВА АНГЛИЙСКИЙ ЯЗЫК EXTRA READING COURSE Учебно-методическое пособие МИНИСТЕРСТВО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ И НАУКИ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ Федеральное государственное бюджетное образовательное учреждение высшего образования «Южно-Уральский государственный гуманитарно-педагогический университет» К.А. Астахова, Р.Х. Дмитриева, Е.А. Иванова, В.В. Мошкович, Н.В. Подковырова АНГЛИЙСКИЙ ЯЗЫК EXTRA READING COURSE Учебно-методическое пособие Челябинск, 2018 1 УДК 42-8(021) ББК 81.432.1-923 А 64 Астахова, К.А. Английский язык: Extra Reading Course: учебно-методическое пособие / К.А. Астахова, Р.Х. Дмитриева, Е.А. Иванова, В.В. Мошкович, Н.В. Подковырова. – Челябинск: Изд-во Южно-Урал. гос. гуман.-пед. ун-та, 2018. – 204 с. ISBN 978-5-91155-065-3 Методическое пособие предназначено для студентов I–V курсов факультета иностранных язы- ков для проведения лабораторных работ по курсу «Домашнее чтение», а также может быть ис- пользовано для самостоятельной работы в рамках дисциплины Практика устной и письменной речи для подготовки студентов специальности «Иностранный язык. Иностранный язык», «Перевод и переводоведение». Цель пособия – развить навыки интенсивного и экстенсивного чтения. Структура учебного курса представляет собой два раздела, в первом уделяется внимание интенсивному чтению. Данный раздел состоит из пяти глав, в каждой из которых две части. Одна структурная часть включает в себя разработку заданий к выбранному курсом художе- ственному произведению современного британского писателя. Во втором разделе представле- ны задания для экстенсивного чтения. Всего в разделе три главы, в каждой из которых разра- ботки к двум художественным произведениям современных британских писателей. Рецензенты: Т.Ю. Передриенко, канд. филол. наук, доцент О.Ю. Афанасьева, д-р пед. -

Crime Fiction / John Scaggs

running head recto i CRIME FICTION Crime Fiction provides a lively introduction to what is both a wide- ranging and a hugely popular literary genre. Using examples from a variety of novels, short stories, films and television series, John Scaggs: • presents a concise history of crime fiction – from biblical narratives to James Ellroy – broadening the genre to include revenge tragedy and the gothic novel • explores the key sub-genres of crime fiction, such as ‘Mystery and Detective Fiction’, ‘The Hard-Boiled Mode’, ‘The Police Procedural’ and ‘Historical Crime Fiction’ • locates texts and their recurring themes and motifs in a wider social and historical context • outlines the various critical concepts that are central to the study of crime fiction, including gender studies, narrative theory and film theory • considers contemporary television series such as C.S.I.: Crime Scene Investigation alongside the ‘classic’ whodunnits of Agatha Christie Accessible and clear, this comprehensive overview is the essential guide for all those studying crime fiction and concludes with a look at future directions for the genre in the twenty-first century. John Scaggs is a Lecturer in the Department of English at Mary Immaculate College in Limerick, Ireland. THE NEW CRITICAL IDIOM Series Editor: John Drakakis, University of Stirling The New Critical Idiom is an invaluable series of introductory guides to today’s critical terminology. Each book: . provides a handy, explanatory guide to the use (and abuse) of the term . offers an original and distinctive overview by a leading literary and cultural critic . relates the term to the larger field of cultural representation With a strong emphasis on clarity, lively debate and the widest possible breadth of examples, The New Critical Idiom is an indispensable approach to key topics in literary studies.