Popjustice, Volume 4: Understanding the Entertainment Industry by Thelma Adams, Michael Ahn, Liz Manne with Ranald T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

100 Projects in Haiti

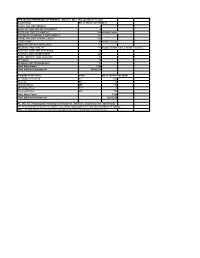

Haiti Assistance Program (HAP) Projects and Partnerships Project Name Implemented by Project Agreement Start Date End Date Status Description Emergency Relief Food rations for over 1 million people and associated distribution costs, primarily to young mothers and children through Contribution to Food Distribution WFP $ 29,929,039.10 19-Jan-10 31-Dec-10 Closed a partnership with the UN World Food Programme. Contributions to the IFRC Earthquake Appeal covered the purchase of tarps/tents, hygiene kits, non-food items, shipping, transportation and general infrastructure costs to mount these distributions such as purchase of vehicles and generators. The American Red Cross also donated nearly 3 million packaged meals for distribution in the early days of Domestic Heater Meals ARC $ 14,224,831.00 2010 2010 Closed the response. These funds also contributed to Base Camp set-up which was the main operational hub in Port-au-Prince in the relief and early recovery phases. Contributions to the IFRC Earthquake Appeal covered the purchase of tarps/tents, hygiene kits, non-food items, shipping, transportation and general infrastructure costs to mount these distributions such as purchase of vehicles and generators. These funds also contributed to Base Camp set-up which was the main operational hub in Port-au-Prince in Contribution to IFRC Appeal IFRC $ 6,535,937.00 2010 2012 Closed the relief and early recovery phases. Contributions to the ICRC Earthquake Appeal totaled $4,169,518, distributed across various sectors as follows: Relief $3,612,064, Shelter -

Special Issue

ISSUE 750 / 19 OCTOBER 2017 15 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week } Post Malone scored Leave A Light On Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 with “sneaky” Tom Walker YouTube scheme. Relentless Records (Fader) out now Tom Walker is enjoying a meteoric rise. His new single Leave } Spotify moves A Light On, released last Friday, is a brilliant emotional piano to formalise pitch led song which builds to a crescendo of skittering drums and process for slots in pitched-up synths. Co-written and produced by Steve Mac 1 as part of the Brit List. Streaming support is big too, with top CONTENTS its Browse section. (Ed Sheeran, Clean Bandit, P!nk, Rita Ora, Liam Payne), we placement on Spotify, Apple and others helping to generate (MusicAlly) love the deliberate sense of space and depth within the mix over 50 million plays across his repertoire so far. Active on which allows Tom’s powerful vocals to resonate with strength. the road, he is currently supporting The Script in the US and P2 Editorial: Paul Scaife, } Universal Music Support for the Glasgow-born, Manchester-raised singer has will embark on an eight date UK headline tour next month RotD at 15 years announces been building all year with TV performances at Glastonbury including a London show at The Garage on 29 November P8 Special feature: ‘accelerator Treehouse on BBC2 and on the Today Show in the US. before hotfooting across Europe with Hurts. With the quality Happy Birthday engagement network’. Recent press includes Sunday Times Culture “Breaking Act”, of this single, Tom’s on the edge of the big time and we’re Record of the Day! (PRNewswire) The Sun (Bizarre), Pigeons & Planes, Clash, Shortlist and certain to see him in the mix for Brits Critics’ Choice for 2018. -

Annual Report 2007

_ANNUAL REPORT _2007 _Toronto _Montréal 2 Carlton St. 4200 Saint-Laurent Blvd Suite 1709 Suite 503 Toronto, Ontario M5B 1J3 Montréal, Québec H2W 2R2 Telephone : 416.977.8154 Telephone : 514.845.4418 Fax : 416.977.0694 Fax : 514.845.5498 E-mail : [email protected] E-mail : [email protected] www.bellfund.ca www.fondsbell.ca years _OVERVIEW OF THE BELL BROADCAST AND NEW MEDIA FUND MANDATE FINANCIAL PARTICIPATION - PRODUCTION PROGRAM To advance the Canadian broadcasting system, the Bell Fund encourages and funds the creation of excellent Canadian digital media, promotes partnerships • The new media component is eligible for a grant not to exceed ELIGIBLEand sustainable APPLICANTS businesses in the broadcast and new media sectors, engages 75% of its costs of production to a maximum of $250,000. in research and sharing knowledge and enhances the national and international profile of industry stakeholders. • The new media component is also eligible for a bonus to match any broadcaster cash contribution, to a maximum of $100,000. • The television component is eligible for a grant based on 75% • Must be Canadian, and in the case of a company, of the broadcast licence fee to a maximum of $75,000. must be Canadian-controlled. ELIGIBLE PROJECTS FINANCIAL• The PARTICIPATION television component - eligibility amount may be doubled • Must be an independent producer or broadcaster-affiliated DEVELOPMENT to a maximum PROGRAM of $150,000, if the program is shot and broadcast production company. in High Definition HD format (“HD Bonus”) • Must include both a new media component as well as a television component. • The new media component is eligible for a grant not to exceed 75% of the costs of development to a maximum of $50,000. -

The SRAO Story by Sue Behrens

The SRAO Story By Sue Behrens 1986 Dissemination of this work is made possible by the American Red Cross Overseas Association April 2015 For Hannah, Virginia and Lucinda CONTENTS Foreword iii Acknowledgements vi Contributors vii Abbreviations viii Prologue Page One PART ONE KOREA: 1953 - 1954 Page 1 1955 - 1960 33 1961 - 1967 60 1968 - 1973 78 PART TWO EUROPE: 1954 - 1960 98 1961 - 1967 132 PART THREE VIETNAM: 1965 - 1968 155 1969 - 1972 197 Map of South Vietnam List of SRAO Supervisors List of Helpmate Chapters Behrens iii FOREWORD In May of 1981 a group of women gathered in Washington D.C. for a "Grand Reunion". They came together to do what people do at reunions - to renew old friendships, to reminisce, to laugh, to look at old photos of them selves when they were younger, to sing "inside" songs, to get dressed up for a reception and to have a banquet with a speaker. In this case, the speaker was General William Westmoreland, and before the banquet, in the afternoon, the group had gone to Arlington National Cemetery to place a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. They represented 1,600 women who had served (some in the 50's, some in the 60's and some in the 70's) in an American Red Cross program which provided recreation for U.S. servicemen on duty in Europe, Korea and Vietnam. It was named Supplemental Recreational Activities Overseas (SRAO). In Europe it was known as the Red Cross center program. In Korea and Vietnam it was Red Cross clubmobile service. -

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written By

TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gould, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Beckett; AMC The Good Wife, Written by Meredith Averill, Leonard Dick, Keith Eisner, Jacqueline Hoyt, Ted Humphrey, Michelle King, Robert King, Erica Shelton Kodish, Matthew Montoya, J.C. Nolan, Luke Schelhaas, Nichelle Tramble Spellman, Craig Turk, Julie Wolfe; CBS Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, William E. Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Barbara Hall, Patrick Harbinson, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm, Charlotte Stoudt, James Yoshimura; Showtime House Of Cards, Written by Kate Barnow, Rick Cleveland, Sam R. Forman, Gina Gionfriddo, Keith Huff, Sarah Treem, Beau Willimon; Netflix Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Janet Leahy, Erin Levy, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner, Carly Wray; AMC COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Luke Del Tredici, Tina Fey, Lang Fisher, Matt Hubbard, Colleen McGuinness, Sam Means, Dylan Morgan, Nina Pedrad, Josh Siegal, Tracey Wigfield; NBC Modern Family, Written by Paul Corrigan, Bianca Douglas, Megan Ganz, Abraham Higginbotham, Ben Karlin, Elaine Ko, Steven Levitan, Christopher Lloyd, Dan O’Shannon, Jeffrey Richman, Audra Sielaff, Emily Spivey, Brad Walsh, Bill Wrubel, Danny Zuker; ABC Parks And Recreation, Written by Megan Amram, Donick Cary, Greg Daniels, Nate DiMeo, Emma Fletcher, Rachna -

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 Through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No. of Stories per Subject AGING AND RETIREMENT 5 AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT 76 ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT 149 includes Sports BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND FINANCE 103 CRIME AND LAW ENFORCEMENT 168 EDUCATION 42 includes College IMMIGRATION AND REFUGEES 51 MEDICINE AND HEALTH 171 includes Health Care & Health Insurance MILITARY, WAR AND VETERANS 26 POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT 425 RACE, IDENTITY AND CULTURE 85 RELIGION 19 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 79 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 Program Codes (Pro) Code No. of Stories per Show All Things Considered AT 645 Fresh Air FA 41 Morning Edition ME 513 TED Radio Hour TED 9 Weekend Edition WE 191 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 AT, ME, WE: newsmagazine featuring news headlines, interviews, produced pieces, and analysis FA: interviews with newsmakers, authors, journalists, and people in the arts and entertainment industry TED: excerpts and interviews with TED Talk speakers centered around a common theme Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Aging and Retirement ALL THINGS CONSIDERED 03/23/2021 0:04:22 Hit Hard By The Virus, Nursing Homes Are In An Even More Dire Staffing Situation Aging and Retirement WEEKEND EDITION SATURDAY 03/20/2021 0:03:18 Nursing Home Residents Have Mostly Received COVID-19 Vaccines, But What's Next? Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/15/2021 0:02:30 New Orleans Saints Quarterback Drew Brees Retires Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/12/2021 0:05:15 -

Emeline Michel

EMELINE MICHEL PHOTO BY GREGORY F. REED Artist Partner Program presents EMELINE MICHEL Friday, November 6, 2015 . 8PM Ina & Jack Kay Theatre Emeline Michel, vocals Yayoi Ikawa, piano Calvin Jones, bass Ben Nicholas, drums Jean Guy Rene, conga Community Partner: Fonkoze USA Campus Partners: Caribbean Students Association, Global Communities Living/ Learning Program and the Alternative Breaks Program at Adele H. Stamp Student Union This performance will last approximately 1 hour and 15 minutes, with no intermission. Video or audio recording of the production is strictly prohibited. Join the artists for a conversation with the audience following the performance. 4 ARTIST STATEMENT virtuoso vocal, singing in Creole, French and English, with finger-picked guitars, soulful backing Being an artist from Haiti I inherited the precious vocals, a children’s choir, Haitian percussion, gift to be in the moment. lush strings, playful trumpet and accordion lines. Visit www.facebook.com/emelinemichelmusic Always remembering that only “Now” is truly ours. for more information. The stage for me is a sacred place, a full circle, where the audience is half, the band and myself the other THE CLARICE AND half. And our repertoire always leaves room for spontaneous moments. THE COMMUNITY Being one... in a chant... a dance, never the same The Clarice is building the future of the arts by at each show. training, mentoring and presenting the next I cannot wait to experience and create this magic generation of artists and creative innovators. As with Maryland. artists develop their craft as performers, they must become instigators of meaningful dialogue, creative research and audience connection. -

Rapport D'activité 2012-2013 Fonds De Développement Et De

2012-2013 RAPPORT D’ACTIVITÉ Fonds de développement et de reconnaissance des compétences de la main-d’œuvre RAPPORT D’ACTIVITÉ COMMISSION DES PARTENAIRES DU MARCHÉ DU TRAVAIL FONDS DE DÉVELOPPEMENT ET DE RECONNAISSANCE DES COMPÉTENCES DE LA MAIN-d’œUVRE RAPPORT D’ACTIVITÉ 2012-2013 On peut consulter le présent document dans le site de la Commission des partenaires du marché du travail, à l’adresse www.cpmt.gouv.qc.ca. RÉDACTION Direction du soutien au développement de la main-d’œuvre Commission des partenaires du marché du travail ÉDITION Direction des communications Ministère de l’Emploi et de la Solidarité sociale Dépôt légal – Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, 2013 Dépôt légal – Bibliothèque et Archives Canada, 2013 ISBN : 978-2-550-68970-6 (imprimé) ISBN : 978-2-550-68971-3 (PDF) © Gouvernement du Québec MONSIEUR JACQUES CHAGNON Président de l’Assemblée nationale du Québec Hôtel du Parlement Québec (Québec) G1A 1A4 MONSIEUR LE PRÉSIDENT, Conformément aux articles 41 et 42 de la Loi favorisant le développement et la reconnaissance des compétences de la main-d’œuvre, j’ai l’honneur de vous soumettre le rapport d’activité concernant son application, ainsi que les états financiers du Fonds de développement et de reconnaissance des compétences de la main-d’œuvre pour l’exercice financier ayant pris fin le 31 mars 2013. Je vous prie d’agréer, Monsieur le Président, l’expression de mes sentiments les meilleurs. La ministre de l’Emploi et de la Solidarité sociale, ministre du Travail, ministre responsable de la Condition féminine, -

Televi and G 2013 Sion, Ne Graphic T 3 Writer Ews, Rad

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 6, 2012 2013 WRITERS GUILD AWARDDS TELEVISION, NEWS, RADIO, PROMOTIONAL WRITING, AND GRAPHIC ANIMATION NOMINEES ANNOUNCED Los Angeles and New York – The Writers Guild of Ameerica, West (WGAW) and the Writers Guild of America, East (WGAE) have announced nominaations for outstanding achievement in television, news, radio, promotional writing, and graphic animation during the 2012 season. The winners will be honored at the 2013 Writers Guild Awards on Sunday, February 17, 2013, at simultaneous ceremonies in Los Angeles and New York. TELEVISION NOMINEES DRAMA SERIES Boardwalk Empire, Written by Dave Flebotte, Diane Frolov, Chris Haddock, Rolin Jones, Howard Korder, Steve Kornacki, Andrew Schneider, David Stenn, Terence Winter; HBO Breaking Bad, Written by Sam Catlin, Vince Gilligan, Peter Gouldd, Gennifer Hutchison, George Mastras, Thomas Schnauz, Moira Walley-Becckett; AMC Game of Thrones, Written by David Benioff, Bryan Cogman, George R. R. Martin, Vanessa Taylor, D.B. Weiss; HBO Homeland, Written by Henry Bromell, Alexander Cary, Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Chip Johannessen, Meredith Stiehm; Showtime Mad Men, Written by Lisa Albert, Semi Chellas, Jason Grote, Jonathan Igla, Andre Jacquemetton, Maria Jacquemetton, Brett Johnson, Janeet Leahy, Victor Levin, Erin Levy, Frank Pierson, Michael Saltzman, Tom Smuts, Matthew Weiner; AMC -more- 2013 Writers Guild Awards – TV-News-Radio-Promo Nominees Announced – Page 2 of 7 COMEDY SERIES 30 Rock, Written by Jack Burditt, Kay Cannon, Robert Carlock, Tom Ceraulo, Vali -

Suspense Magazine August 2013

Suspense, Mystery, Horror and Thriller Fiction September/OctOber 2013 Tricks & Treats With L.L. SoareS John rector Steven Gore Linda FairStein Peek InsIde new Releases From Wendy Corsi staub Paul d. Parsons & Debut Author tasha alexander Barry Lancet Joins Anthony J. FrAnze On Writing Killing Time in Nashville with DaviD ingram C r e di t s From the Editor John Raab President & Chairman Shannon Raab Writing is essential for everyday living and Creative Director growing. Writing a good book is something that is Romaine Reeves not easy to accomplish. However, if you do one very CFO simple thing, fans and readers will keep coming back to your books, because they know they will Starr Gardinier Reina Executive Editor get the straight story told to them. I’ll sum it up in one word: research! Jim Thomsen Just as writing and reading have been around Copy Editor since man has walked the earth, research has also Contributors been around. One of the oldest questions an author Donald Allen Kirch can get in an interview—and having interviewed hundreds of them, it’s one I’ve never Mark P. Sadler asked—is, “Where do you get your inspiration from?” Susan Santangelo DJ Weaver That is a personal question, and one that really has no value to the author at all CK Webb and shouldn’t to the reader. A more appropriate question to ask would be: “How much Kiki Howell Kaye George research did you have to do in order to get it right in your book?” This one question will Weldon Burge let the reader know just how important not only the subject is to the author, but how Ashley Wintters much time they spent on getting it right. -

A Lexico-Semantic Analysis of Philippine Indie Song Lyrics Written in English

Available online at www.jlls.org JOURNAL OF LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTIC STUDIES ISSN: 1305-578X Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 14(4), 12-31; 2018 A lexico-semantic analysis of Philippine indie song lyrics written in English Johann Christian V. Rivera a , Alejandro S. Bernardo b * a University of Santo Tomas, España, Manila, 1015, Philippines b University of Santo Tomas, España, Manila, 1015, Philippines APA Citation: Rivera, J.C.V., & Bernardo, A.S. (2018). A lexico-semantic analysis of Philippine indie song lyrics written in English. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 14(4), 12-31. Submission Date: 10/09/2017 Acceptance Date: 02/07/2018 Abstract The power of music to entertain and to affect people psychologically makes it a significant part of human society and a ripe field for empirical investigations. Researches about music’s psychological and physiological effects on people as well as music’s pedagogical value in language teaching and learning have shown interesting results. However, there still remains a dearth of empirical studies that look into the purported meanings of songs unearthed through linguistic lenses. This study, therefore, examines the intersection of music and linguistics by conducting a lexico-semantic analysis of 30 indie songs written in English by three Filipino indie musicians. One key finding is that indie songs are not usually unclear contrary to the popular belief that they generally tend to be nebulous and require deliberate disambiguation. © 2018 JLLS and the Authors - Published by JLLS. Keywords: Original Philippine Music; indie music; lexical semantics; semantic analysis 1. Introduction Music plays a significant part in man’s daily life undoubtedly because of its appeal to the ears. -

Macy's Honors Generations of Cultural Tradition During Asian Pacific

April 30, 2018 Macy’s Honors Generations of Cultural Tradition During Asian Pacific American Heritage Month Macy’s invites local tastemakers to share stories at eight stores nationwide, including the multitalented chef, best-selling author, and TV host, Eddie Huang in New York City on May 16 NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- This May, Macy’s (NYSE:M) is proud to celebrate Asian Pacific American Heritage Month with a host of events honoring the rich traditions and cultural impact of the Asian-Pacific community. Joining the celebrations at select Macy’s stores nationwide will be chef, best-selling author, and TV host Eddie Huang, beauty and style icon Jenn Im, YouTube star Stephanie Villa, chef Bill Kim, and more. This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20180430005096/en/ Macy’s Asian Pacific American Heritage Month celebrations will include special performances, food and other cultural elements with a primary focus on moderated conversations covering beauty, media and food. For these multifaceted conversations, an array of nationally recognized influencers, as well as local cultural tastemakers will join the festivities as featured guests, discussing the impact, legacy and traditions that have helped them succeed in their fields. “Macy’s is thrilled to host this talented array of special guests for our upcoming celebration of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month,” said Jose Gamio, Macy’s vice president of Diversity & Inclusion Strategies. “They are important, fresh voices who bring unique and relevant perspectives to these discussions and celebrations. We are honored to share their important stories, foods and expertise in conversations about Asian and Pacific American culture with our customers and communities.” Multi-hyphenate Eddie Huang will join the Macy’s Herald Square event in New York City for a discussion about Asian representation in the media.